Israel on the Hudson

The great big city’s a wondrous toy, / just made for a girl and boy. / We’ll turn Manhattan into an isle of joy,” cheered Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart in their bright and bubbly 1925 salute, “Manhattan.” Chock-a-block with geographical references to the Lower East Side and Greenwich Village, Coney Island and Flatbush, “the Bronx and Staten Island too,” the song could very well serve as the anthem of New York’s Jews.

Their allegiance to the five boroughs fuels City of Promises: A History of the Jews of New York, an ambitious, three-volume work that attempts to capture and make sense of the entangled relationship between the New World’s greatest, most populous, city and its vast number of Jewish inhabitants. As virtually everyone knows, that relationship gave rise to some of the most emblematic of modern Jewish neighborhoods, institutions, and outsized personalities—from the Lower East Side, America’s very first “great ghetto”; to Russ & Daughters, purveyors of smoked fish, bagels, and other delicacies commonly associated with the Big Apple; to Stephen S. Wise, the Lubavitcher Rebbe, and Ed Koch, who was recently eulogized as “tough and loud, brash and irreverent, full of humor and chutzpah . . . [New York City’s] quintessential mayor.” Moving chronologically from the community’s 17th-century origins through the first decade of the 21st century, City of Promises explores, in vivid and generous detail, how and why the Jews came to regard New York, New York as “their special place.”

A synthesis of the latest historical scholarship, whose combined bibliography and footnotes run to more than 150 pages, this project engaged the talents of several generations of American Jewish historians, from Howard B. Rock, professor emeritus at Florida International University and Jeffrey S. Gurock of Yeshiva University, to Annie Polland of the Lower East Side’s Tenement Museum and  Daniel Soyer of Fordham University. Its guiding hand and presiding spirit, though, is that of Deborah Dash Moore, who teaches at the University of Michigan and directs its Frankel Center for Judaic Studies. Her 1981 book, At Home in America: Second Generation New York Jews, reaffirmed the centrality of New York to the American Jewish experience. Grounded as much in the new urban history of the time as it was in modern Jewish history, Moore’s account not only transformed ethnicity from a sociological category into an historical one, it also demonstrated the extent to which modern expressions of Jewishness were inextricably bound up with that cluster of behaviors and sensibilities known as urbanism; the two, we’ve now come to understand, go hand in hand.

Daniel Soyer of Fordham University. Its guiding hand and presiding spirit, though, is that of Deborah Dash Moore, who teaches at the University of Michigan and directs its Frankel Center for Judaic Studies. Her 1981 book, At Home in America: Second Generation New York Jews, reaffirmed the centrality of New York to the American Jewish experience. Grounded as much in the new urban history of the time as it was in modern Jewish history, Moore’s account not only transformed ethnicity from a sociological category into an historical one, it also demonstrated the extent to which modern expressions of Jewishness were inextricably bound up with that cluster of behaviors and sensibilities known as urbanism; the two, we’ve now come to understand, go hand in hand.

In the years since the publication of At Home in America, Professor Moore has ranged widely, ably tackling such disparate phenomena as the Jews of Los Angeles and Miami and the experience of Jewish servicemen in World War II. With City of Promises, she now returns to the subject that first launched her career. One might call it a homecoming of sorts, but this is no sentimental journey. Informed by years of close reading and unusually deep immersion in the sources, Moore’s perspective on the Jewish encounter with New York is anything but starry-eyed. “By the middle of the 20th century, no city offered the Jews more than New York,” she writes. “New York gave Jews visibility as individuals and as a group. It provided employment and education, inspiration and freedom, fellowship and community . . . But by the 1960s and ’70s, the Jews’ love affair with the city soured.” Equally sensitive to both the limits and the possibilities of the Jews’ encounter with the city, Moore makes a point of emphasizing its multiple twists and turns. At times, she notes, the New York Jewish experience more than exceeded its promise, at other moments, it fell short, and at still others, it soured entirely.

20th century, no city offered the Jews more than New York,” she writes. “New York gave Jews visibility as individuals and as a group. It provided employment and education, inspiration and freedom, fellowship and community . . . But by the 1960s and ’70s, the Jews’ love affair with the city soured.” Equally sensitive to both the limits and the possibilities of the Jews’ encounter with the city, Moore makes a point of emphasizing its multiple twists and turns. At times, she notes, the New York Jewish experience more than exceeded its promise, at other moments, it fell short, and at still others, it soured entirely.

A lovely, if not entirely original, conceit that gives the series its name as well as its intellectual scaffolding, the rubric of promise helps to tame the unruliness that lies at the heart of New York’s Jewish story. For if ever there was a messy and uncontainable tale, this is it. Within New York City’s precincts, nothing, not even the past, remained constant for too long. In quick succession, one kind of Jew gave rise to another, as did the various languages in which the community expressed itself. Synagogue minute books recorded the most humdrum of details, first in Portuguese and then in German, Yiddish, Ladino, and English, while newspapers ran the gamut from The American Hebrew and the Jewish Messenger to La Vara and Der Blatt. Meanwhile, life in the Jewish enclave of Kleindeutschland and neighborhoods such as the South Bronx and Harlem, Forest Hills and Boro Park ebbed and flowed, as did the

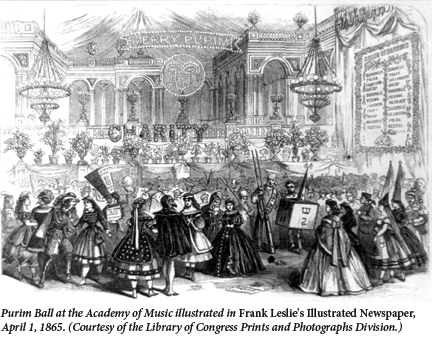

fortunes of those who called these areas home. Self-styled Jewish reverends, aspiring chief rabbis and a bona fide one, too, came and went, as did shopkeepers, union leaders and politicians, do-gooders and garment workers, sign painters, vaudevillians, bundistn and yidishistn, lovers of Zion, fanciers of Purim costume balls, and devotees of modern Hebrew. For a time, the Empire City housed them all.

The city’s designated Jewish spaces were also continuously on the move. Buildings that seemed destined to last forever and that stamped the city as open and hospitable—the exuberant, Moorish-styled, Temple Emanu-El at 43rd and Fifth Avenue with its egg-shaped minarets or turrets and “Saracenic detail,” for instance—were torn down to make way for streamlined office buildings. Heralded by The New York Times as “one of the few distinctly Oriental examples in the panorama of New York architecture,” the building faced the wrecking ball in 1926. Its imminent demise prompted the paper to note glumly that “the sun is about to gild these turrets for the last time . . . Change, change everywhere.”

These days, cultural personalities whose imprint on New York Jewish life once seemed as indelible as Temple Emanu-El barely register with the latest generation of Jewish New Yorkers. Little over a month ago, New York’s The Jewish Week carried a feature piece written by a Hunter College High School senior in which she noted casually that her peers knew not of Woody Allen. (The fact that she was aware of his identity actually set her apart.) “By middle school,” relates Basia Rosenbaum, “I was quoting Woody Allen (even when I didn’t understand the punch lines) to peers who not only had no idea who he was, but erupted in giggle fits over his first name.” If it is Woody Allen’s lot to be consigned to the distant shores of memory, what fate do we hold out for the chronically embattled Gershom Mendes Seixas of Congregation Shearith Israel; the plucky Minnie Louis, founder of the Hebrew Technical School for Girls; or the redoubtable Esther Jane Ruskay, author of that paean to Jewish domesticity, Hearth and Home Essays? Time and again, history has failed to remember many who proudly called New York their home.

Perhaps that’s because the history of New York’s Jews is a giant sprawl of a story, of a piece with the city’s most characteristic geographical feature. Figuring out who to include and who to omit, which moment to highlight and which to minimize, is a thankless enterprise. Someone, somewhere, is sure to feel slighted. With that in mind, perhaps, the publisher of City of Promises makes much of the fact that its three volumes come in a boxed set. At first, I thought this purely a marketing decision wrapped up in an aesthetic gesture: attractively packaged as a unit, housed within a handsome container, City of Promises was made, well, more promising to potential readers, who would be much more likely to purchase all three volumes if they were sold as one. But on second thought, I now take the assemblage to be as much an intellectual statement as a commercial one, a way to house and contain the fluidity and variability of the history that resides within its aggregate 1,000 plus pages. It’s an admission that what lies ahead is a whopping big yarn, a moveable feast of a story.

To be sure, City of Promises adds up to more than the sum of its parts; its impact is a cumulative one. Even so, like the mosaic of neighborhoods that makes up the city, each of its volumes also stands apart-on its own terms and turf. (To bring home that point, all three volumes feature the same Foreword, written by Moore.)

The first volume in the series, Haven of Liberty: New York Jews in the New World, 1654-1865, sets the tone by looking closely at the ways in which New York Jewry first developed under the impress of freedom—or, more specifically still, under the irrepressible conditions of republicanism. “New York’s Jews incorporated American revolutionary ideology into the core of their individual and collective lives,” Howard B. Rock writes, adding, “Republicanism formed the seeds of the city of promises.” Deftly, he limns a portrait of a community learning to make its way.

The first volume in the series, Haven of Liberty: New York Jews in the New World, 1654-1865, sets the tone by looking closely at the ways in which New York Jewry first developed under the impress of freedom—or, more specifically still, under the irrepressible conditions of republicanism. “New York’s Jews incorporated American revolutionary ideology into the core of their individual and collective lives,” Howard B. Rock writes, adding, “Republicanism formed the seeds of the city of promises.” Deftly, he limns a portrait of a community learning to make its way.

Things didn’t always go well. Time and again, New York Jews of the 18th century chafed under the authority of the city’s only synagogue, Shearith Israel. Nothing if not independent-minded, they refused to pay dues or to sit in the seats to which they had been assigned, much less observe the Sabbath or keep kosher. The more hot-headed among them even sought to settle disputes with their fists; brawls and bloodied noses were not uncommon in the years prior to and following the American Revolution.

Eventually, New York’s Jewish residents learned to avoid conflict, or at least to minimize it, by forming congregations of their own where like-mindedness prevailed. Alternatively, they sought community and companionship in more avowedly secular institutions of the mid-19th century such as B’nai B’rith, a fraternal organization, or the Jewish Clerks Aid Society, a philanthropic one, where the “horse-race speed” of the traditional weekday service was no longer of concern and keeping kosher had ceased to be the “diploma of a good Jew.” A wider world, and with it a bounty of new opportunities, beckoned enticingly, which the Jews of antebellum New York made quick to harvest.

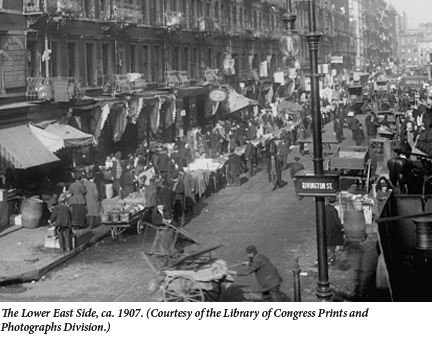

Though it overlaps somewhat with Rock’s account, the second volume of the series, Emerging Metropolis: New York Jews in the Age of Immigration, 1840-1920, chronicles New York Jewry’s explosive growth throughout the latter half of the 19th century and the first two decades of the 20th. Sensitively drawn by Annie Polland and Daniel Soyer, this account trains its sights on the “story of how New York became the greatest Jewish metropolis of all time.” Numbers had everything to do with it. In 1840, there were approximately seven thousand Jews in the Empire City. By 1920, their ranks had ballooned to more than a million and a half, the consequence of massive immigration from abroad. Hard as it is to imagine, New York Jewry was once so small a community that it was possible to tabulate its size based on how many people in the city purchased matzah for Passover. As the number of Jewish residents grew and grew, such informal tallies inevitably gave way to much more methodologically sophisticated and impersonal forms of accounting—a telling index of change.

Equally telling was New York Jewry’s increasing heterogeneity. Throughout the latter half of the 19th century, the Jewish community was populated by “brownstone Jews,” whose strong attachment to politesse, discretion, and other conventions of bourgeois behavior resulted in low-key, restrained forms of Jewish expression. By 1900, “tenement Jews,” with their own highly differentiated and much more public norms of social behavior, would set a new tone. Fragmentation rather than unity became the order of the day.

Some New York Jews were quick to rue the Jewish community’s metamorphosis into a hotbed of fiercely held, competing allegiances. In 1910, seeking consensus, as well as a form of social control, they formed the Kehillah, a community-wide umbrella group—a “municipal government” is what one of its champions, Judah Magnes, called it—whose portfolio encompassed everything from what New York Jews ate and in what language they prayed (or didn’t) to how their children spent their leisure time (at the movies). I suspect that the reader will not be terribly surprised to learn that this noble venture did not succeed, though it certainly wasn’t for want of trying. By then, you see, New York Jews—the contentious, passionate, unmanageable mass of them—had come into their own.

The third and final volume in the series, Jews in Gotham: New York Jews in a Changing City, 1920-2010, takes the story up to the present day. With Jeffrey S. Gurock as its surefooted guide, the landscape of New York becomes an increasingly familiar one. Many local readers are apt to recognize themselves-and their city-in its pages. Much of the text focuses on the changing face of the urban landscape, when, in the wake of World War II, new Jewish neighborhoods took root. “Neighborhoods in every borough approached, each in their own differing ways, the opportunities and challenges that this city of promises presented and posed,” writes Gurock. By the 1960s, Queens Boulevard in Forest Hills became a “Jewish avenue,” giving Riverside Park and the Williamsburg Bridge promenade a run for their money. Meanwhile, the planned Bronx community of Co-op City-“for friendly people living together”-drew anywhere from twenty-five thousand to forty thousand Jewish residents.

Gurock’s narrative also gives pride of place to that bewildering mix of postwar cultural phenomena that transcended local boundaries, among them the Soviet Jewry movement, feminism, and the revival of Orthodoxy on one side of the ledger and the souring of Black-Jewish relations on the other. Although Jews in Gotham has more than its fair share of little-known institutions and events, from the Trylon—a West Bronx boys club, which inventively took its name from one of the 1939 World’s Fair’s most emblematic structures—to the Jewish Education Committee’s “Children’s Solemn Assembly of Sorrow and Protest” of 1943, those who inhabit its pages—Bella Abzug, Michael Bloomberg, Howard Cosell, Ed Koch, Ralph Lauren, Natan Sharansky—are household names. By the time we put down Jews in Gotham, we’ve come home.

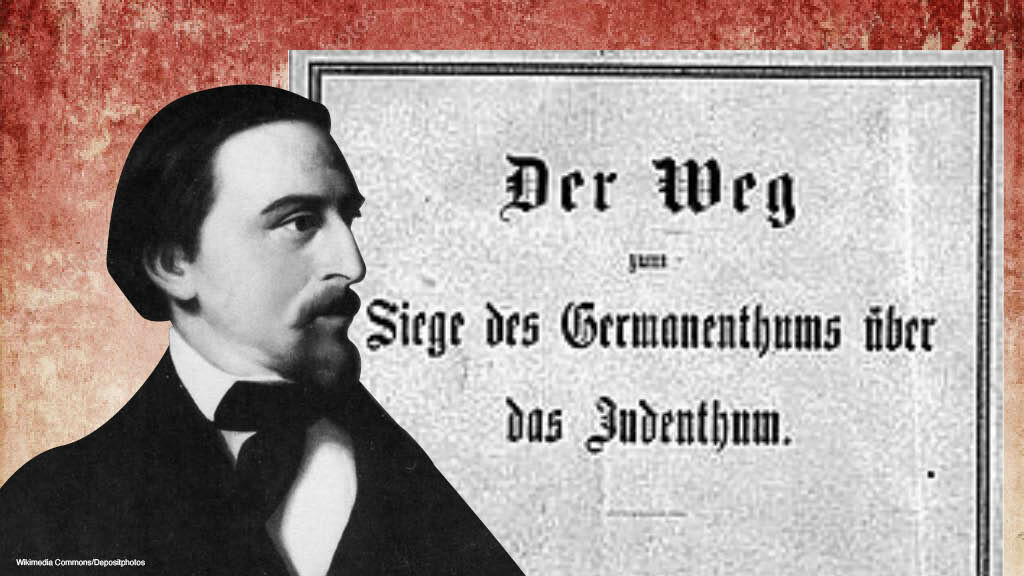

Each of the three volumes in the series is also accompanied by a “visual essay” by Diana L. Linden, an art historian and museum educator. Drawing on objects, images and art, her perspective, we are told, “suggests alternative narratives drawn from a record of cultural production . . . Her view runs as a counterpoint and complement to the historical accounts.” Much as I applaud the notion of fully incorporating non-textual materials into the repertoire of sources that constitute the historical record and for taking one’s interpretive cues from things as well as words, both the placement and substance of Linden’s “visual essays” work against this practice. For one thing, they are positioned  at the end of each volume, where they function more as afterthoughts than as equal partners, let alone as interpretive “counterpoints.” For another, the editorial treatment of the visual materials seems rather grudging. To shine, they need space, otherwise their presence doesn’t register. Time and time again, the reproductions of engravings, maps, paintings, advertisements, and photographs-both of people and objects-are simply not given their due. More disappointing still, the contents of these visual essays leave something to be desired, their selection is uneven at worst and overly familiar at best, and their accompanying interpretation jejune and obvious. A missed opportunity, they do not go nearly far enough.

at the end of each volume, where they function more as afterthoughts than as equal partners, let alone as interpretive “counterpoints.” For another, the editorial treatment of the visual materials seems rather grudging. To shine, they need space, otherwise their presence doesn’t register. Time and time again, the reproductions of engravings, maps, paintings, advertisements, and photographs-both of people and objects-are simply not given their due. More disappointing still, the contents of these visual essays leave something to be desired, their selection is uneven at worst and overly familiar at best, and their accompanying interpretation jejune and obvious. A missed opportunity, they do not go nearly far enough.

Much the same can be said of City of Promises. Taken as a whole, it falls short of its considerable promise. Dutiful rather than inspired, its trajectory does not quite match the grandeur of its subject. I wanted to be swept away by the narrative, caught up in the details, transfixed by a novel interpretation, heartened by a fresh turn of phrase, riveted by a striking image. Alas, that didn’t come to pass. My disappointment, I suspect, is a casualty of the series’ structure, which places a premium on chronology. Having to answer to the imperatives of time, each volume crams an inordinate amount of material into its pages, leaving little opportunity for daydreaming. The text covers a lot of ground but at the expense of a synthetic, freewheeling, thematic approach to the glorious material at hand. Compounding matters, the series’ armature—its leitmotif of promises made and lost—seems to constrain its authors rather than free them to be at their discursive best. Fidelity rather than imagination rules this roost.

Surely it is no coincidence that City of Promises puts me in mind of the recently opened core exhibition at the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia. Both sweeping gestures of interpretation, they reflect the difficulties inherent in the master narrative approach to history. The core exhibition, like City of Promises, is the handiwork of a most accomplished band of historians. It, too, encompasses a vast array of material. It, too, is propelled by an overarching interpretation—that of freedom. And in the end, it, too, leaves me hungering for more.

Close kin, both the books and the exhibition lack fire in the belly. They’re too cautious, restrained, and tamped down by half. Where, I wonder, is the pep and the exhilaration, the fun and the razzmatazz, the urgency and the speed and the noise and the spirit of hefker? Where, oh where, is the expansiveness and, yes, the sheer incommensurability of it all? Perhaps this is something that only poetry can do. Consider these lines of A. Leyeles’ Yiddish poem of 1918, “New York,” (translated by Benjamin Harshav). They really do the city justice.

Metal. Granite. Uproar. Racket. Clatter.

Automobile. Bus. Subway. El.

Burlesque. Grotesque. Café. Movie-theater.

Electric light in screeching maze. A spell.

Suggested Reading

An Old-New Bigotry? A Response

Both Jonathan Karp’s and Reviel Netz’s essays are written in the shadow of October 8—not the day of the unthinkably brutal Hamas massacre in southern Israel, but the day after.

Irving Kristol, Edmund Burke, and the Rabbis

Irving Kristol started off as a neo-Trotskyite and famously became the “godfather of neoconservatism.” But his idiosyncratic “neo-Orthodoxy” lasted a lifetime.

Moses Mendelssohn Street

Immortality in Jerusalem.

Harvard, SNCC, and an Antisemitic Cartoon

How did Harvard students end up using a decades old antisemitic cartoon in their anti-Israel activism?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In