Irving Kristol, Edmund Burke, and the Rabbis

Renowned as a founder of neoconservativism, Irving Kristol was “neo” in other respects as well. “Is there such a thing as a ‘neo’ gene?” he once asked, because, if there was, he certainly had it. By his own account, before he became a neoconservative, he was a neo-Marxist, a neo-Trotskyite, a neo-socialist, and a neoliberal. But “one ‘neo’,” he acknowledged, “has been permanent throughout my life, and it is probably at the root of all the others. I have been ‘neo-Orthodox’ in my religious views (though not in my religious observance).”

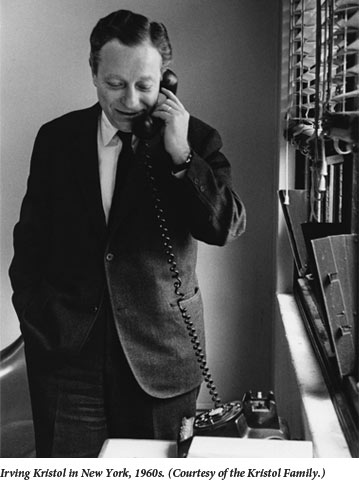

Kristol passed away in 2009 and this posthumous collection of essays, spanning his career, has been widely reviewed by political allies and foes seeking to assess his achievement. Like Neo-Conservatism: The Autobiography of an Idea, his influential collection of essays published in 1999, The Neoconservative Persuasion demonstrates Kristol’s concern with a wide range of historical, cultural, sociological, and other matters. This new volume differs from its predecessor, however, in that it includes a significant representation of his writings on Jews and Judaism. Gertrude Himmelfarb, the editor of this collection and Kristol’s wife, clearly wished to give adequate attention to the “abiding interest in and respect for religion” that led him to identify himself as a “neo-Orthodox Jew.” Nonetheless, most reviewers have spent little time thinking through what this meant to Kristol.

A good clue to the answer can be found in one of his later essays, “On the Political Stupidity of the Jews.” Kristol there recounts an experience that his wife once had while teaching a graduate course on British political thought in which she had spent several sessions on the writings of Edmund Burke. At the end of one class, she was approached by a “quiet and industrious” young woman. “Now,” this student said, “I know why I am Orthodox.” Needless to say, this wasn’t because Burke had supplied an incontrovertible proof that the Oral Torah had been revealed at Mt. Sinai. “What she meant was that she could now defend Orthodoxy in terms that made sense to the non-Orthodox, because she could now defend a strong deference to tradition, which is the keystone of any orthodoxy, in the language of rational secular discourse, which was the language in which Burke wrote.”

Like this graduate student, Irving Kristol himself felt the tug of tradition and admired the way in which Burke upheld the right of “the dead” to have a vote “in deciding on the ordering of our government and society because of the wisdom which we may gain from the ideas which they had derived from experience.”

At the same time, Kristol held that a genuinely Jewish reverence for tradition—a genuinely Jewish conservatism—must be more than a desire to preserve the past. When he was a young editor at Encounter, he tells us, he received an unsolicited essay from Michael Oakeshott, one of the fathers of British conservatism. In lyrical prose, Oakeshott described the conservative disposition as preferring “the tried to the untried, fact to mystery, the actual to the possible, the limited to the unbounded, the near to the distant . . . the convenient to the perfect, present laughter to utopian bliss.” Kristol read the essay, loved every line, and rejected it. For Oakeshott’s vision, he wrote, was “irredeemably secular, as I—being a Jewish conservative—am not.” “Our scriptures and our daily prayer book link us,” Kristol proclaimed:

to the past and to the future with an intensity lacking in Oakeshott’s vision. Judaism, for all its this-worldly focus, also believes that the whole purpose of sanctifying the present is to prepare humanity for a redemptive future.

In several essays, Kristol links Judaism’s reverence for the past with its “rabbinic” aspect, and its longing for the as yet unrealized future with its “prophetic” aspect, and describes the genuinely Jewish worldview as a combination of both of them. Modern Jews, on the other hand, as Kristol sees it, have too often been guilty of disregarding the richness of tradition, both Jewish and Western, in order to make the world anew—in the name of Judaism, but in the spirit of the Enlightenment. Above all, in his view, such Jews have turned against rabbinic tradition and the restraint it put on the utopian elements of Judaism. “To simplify considerably,” Kristol writes, Jews engaged a “sharp shift in emphasis from the ‘rabbinic’ elements in the Jewish tradition to the ‘prophetic’ elements.” They then merged prophetic Judaism with secularism “to create what can fairly be described as a peculiarly intense, Jewish, secular humanism.” This shift was “part and parcel of the emerging messianic sensibility—in matters political, social, and economic—that the Revolution established throughout European society.” It is this ethos that “infused itself into all non-Orthodox versions of contemporary Judaism.”

One of Kristol’s earliest complaints about this modern transformation of Judaism can be found in his 1948 review of Milton Steinberg’s book Basic Judaism, which aimed to establish Jewish doctrines that Jews of all denominations could accept. Yet for Kristol, such a “basic” version of Judaism, insufficiently connected to the rigorous rabbinic past, results in “the transformation of messianism into a shallow, if sincere, humanitarianism, plus a thoroughgoing insensitivity to present-day spiritual problems. Steinberg’s Basic Judaism, according to Kristol, was essentially a theological justification of liberalism, which at its core is essentially an accommodation of “religious views with facility to the outlook of an American ‘Main Street’ in its New Deal variant.”

Kristol was not then—and never became—an enemy of FDR’s policies (that was what made his conservatism neo-), but he rejected the idea that this could be the essence of Judaism: “What are we to make of a rabbi who claims for the Mishnah and the Talmud the right to strike—thereby providing Holy Writ with the satisfaction of having paved the way for the National Labor Relations Act!” As Kristol observed, Rabbi Steinberg’s state of mind was all too representative “of a large section of the American rabbinate, and much of the American Jewish tradition in general.”

As modern Jews moved in this new direction, they also became convinced that a secular society is most conducive to individual liberty. But, Kristol felt, in their eagerness to enjoy its blessings, they overlooked something that rabbinic Judaism understood, and that Burke himself eloquently explained: a market economy cannot truly succeed without a society of people who “resolutely defer gratification, sexual as well as financial, so that, despite the freedom granted each individual, the future nonetheless continues to be nourished at the expense of the present.” For rabbinic Judaism, as well as for “the conservative political tradition,” it is religion, and only religion, that “restrains the self-seeking hedonistic impulse so easily engendered by a successful market economy.”

Such thoughts led Kristol to be “neo-Orthodox in his religious views.” At the same time, however, one searches through his essays in vain for any engagement with the tradition that is the foundation of Orthodox Judaism. He correctly noted that if Orthodoxy never succumbed to purely prophetic utopianism, it was because “even today, a student in the yeshiva in his early years never studies the Prophets in isolation from a study of the Pentateuch or the Talmud.” Yet this intellectual whose worldview was deeply informed by a reverence for the classics of Western civilization had little to say, indeed little apparent interest, in the Talmud itself, the study of which essentially dominated Jewish intellectual life for two thousand years.

Kristol’s distance from the rabbinic tradition is tellingly reflected in a 1998 essay in which he compared Judaism and Christianity, describing the latter as the “far more intellectually complex—far more intellectually interesting” of the two. This, he writes, is because Christianity “has absorbed so much Greek neo-Platonism as well as a liberal sprinkling of Gnosticism, in both belief and spirit.” One may indeed grant to Kristol that Jewish works tend to be less systematic in their examinations of doctrinal questions. The freewheeling nature of talmudic discourse makes it impossible for the uninitiated to pick up a tractate and begin to read, the way one can read, say, the Summa Theologica. But that is part of why the Talmud is more intellectually complex than most Christian works, not less so. It is in the Talmud that one truly discovers Jewish tradition in all its vibrancy, and in studying Talmud one sits in on the symposium of generations that constitutes that tradition. Moreover, the discussions that one encounters in the Talmud are not only legal, but also theological and doctrinal. The problem of evil; the nature of Israel’s election; the reasons for the commandments; human nature, body, and soul, are all debated and examined.

It was in reading Rosenzweig, Buber, and Scholem after World War II, Kristol reveals in his autobiographical essay, that he “was delighted to discover that there really could be an intellectual dimension to Judaism.” Yet this discovery never seemed to take him back to the Jewish classics—a strikingly discordant note in the intellectual symphony of a man who sums up his own reverence for tradition as follows:

Meanwhile, for myself, I have reached certain conclusions: that Jane Austen is a greater novelist than Proust or Joyce; that Raphael is a greater painter than Picasso; that T. S. Eliot’s later Christian poetry is much superior to his earlier; that C. S. Lewis is a finer literary and cultural critic than Edmund Wilson; that Aristotle is more worthy of careful study than Marx; that we have more to learn from Tocqueville than from Max Weber; that . . . Well, enough. As I said at the outset, I have become conservative, and whatever ambiguities attach to the term, it should become obvious what it does not mean.

Should not Kristol, then, also consider the possibility Rabbi Akiva and Rabbi Yochanan ben Zakkai, Rav Yochanan and Reish Lakish, Abaye and Rava, Ravina and Rav Ashi—sages of rabbinic Judaism every yeshiva student knows but few modern Jews struggle to engage—might have had more to say about Judaism than Franz Rosenzweig and Gershom Scholem? It is regrettable that, for all his erudition and Burkean reverence for tradition, Kristol did not turn his attention to the Rabbis.

While Orthodox Jews in America can be commended for not seeking to remake the world, they can perhaps be faulted for showing too little interest in it. But it is interest in the world, on the part of the tradition-loyal segment of American Jewry, that is so desperately needed. In the conclusion of his critique of Steinberg, Kristol bemoaned the failure of American Jewish writers to plumb the depths of Jewish writing and address the truly great issues that face modern man:

We are beginning to wonder, and discuss, the question “why Jews are in the world,” even if, to date, we have ended with hoary platitudes. We have scarcely dared to ask “why are goyim in the world?”—an important question, it must be conceded. Perhaps we are afraid that we will not be able to stop there, but will go on to the semi-blasphemous question “why men in the world?” Yet, if theology today is to ask any question, the last one is the most pertinent, whether it be asked by Jew, Protestant, Catholic, or atheist.

Can American Orthodoxy—plumbing the depths of the aforementioned Abaye and Rava, Ravina and Rav Ashi—answer these questions, in a clear and convincing way? I believe so, but admit that it has yet to accomplish this task. Some sectors of Jewish Orthodoxy are unconnected to American intellectual life. Regrettably, others, in the name of a liberal version of Orthodoxy, have begun to embrace aspects of the counterculture whose moral tenets are anything but traditional. Never has there been a greater need for a Judaism that is both unapologetically Orthodox and passionately engaged in the intellectual debates of American life, willing to put forward to American Jewry—and to the world—the case for addressing the issues facing modern man by looking first to the ancients. Whether this can happen remains to be seen, but if it does, I think that it will bear some affinities to Irving Kristol’s “neo-Orthodox” persuasion.

Suggested Reading

The Great Family Circle

Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, “the father of modern Hebrew,” famously raised his own son to be the first child in almost 2,000 years to speak only Hebrew. When Itamar Ben-Avi grew up, he was fascinated by . . . Esperanto. Esther Schor’s new book on L. L. Zamenhof, his would-be universal language, and those who still speak it inspired Stuart Schoffman to revisit the oddly parallel careers of Ben-Yehuda and Zamenhof.

Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29

At the age of 29, David Ben-Gurion was speaking to empty halls across America for the Zionist movement and Leo Strauss was finding the “theological-political predicament” insoluble. As for Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, he was in Berlin worrying about epistemology and halakha. Three portraits of Jewish excellence in the making.

He Shall Not Press His Fellow

Once every seven years, the Torah says, the economic playing field should be leveled, and those trapped in debt should be freed. Even the rabbinic workaround reminds us of the ideal–as I was reminded after my startup foundered in the 2008 financial crisis.

In the City of Killing

The Kishinev pogrom originated in a rumor, widely disseminated and believed around the area that Easter, that the imperial authorities had given permission for several days of uninterrupted violence against the Jews.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In