Jerusalem of the Balkans

On September 28, 2013, masked policemen armed with machine guns arrested 22 members of the neo-Nazi Golden Dawn party, including several representatives to Greece’s parliament. The rise of the anti-immigrant, anti-Jewish group unearths reminders of Greece’s compliance with the Nazis in World War II. In the Spring 2013 issue, Devin E. Naar explored the resurgence of Salonica’s all-but-erased Jewish community, which is growing alongside the rising tide of Greek anti-Semitism.

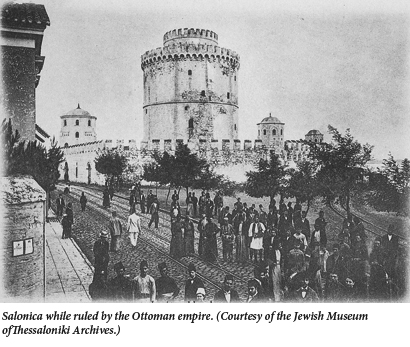

When I told my grandfather that I was going to Salonica for the first time nearly a decade ago, he asked me why. There was “nothing left,” he assured me, by which he meant nothing Jewish. He himself had left as a boy in 1924 and never returned. “There used to be a big tower by the sea,” he informed me. “Maybe it’s still there.” When I told him that the tower still stood, he was pleased. I returned to Salonica again this fall to attend a symposium on the history of the city.

The White Tower, which looks out onto the Mediterranean, is still the iconic symbol of Salonica (Thessaloniki, in Greek). As with much in Greece’s second-largest city, its history is disputed. The Ottomans built the tower in the 16th century, but some locals remember it as a Byzantine or Venetian monument. A few days after I arrived in the city in October 2012, politicians, military, clergy, and thousands of residents, many donning traditional costume, gathered near the tower to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of their city’s liberation from Ottoman rule.

The White Tower, which looks out onto the Mediterranean, is still the iconic symbol of Salonica (Thessaloniki, in Greek). As with much in Greece’s second-largest city, its history is disputed. The Ottomans built the tower in the 16th century, but some locals remember it as a Byzantine or Venetian monument. A few days after I arrived in the city in October 2012, politicians, military, clergy, and thousands of residents, many donning traditional costume, gathered near the tower to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of their city’s liberation from Ottoman rule.

Everyone, including me, gazed out at the sea in anticipation. A navy gunship soon arrived. Officials unloaded an ornate icon depicting Mary and Jesus, brought for the occasion directly from the monasteries of Mount Athos. Bishop Anthimos, the metropolitan of Salonica’s Greek Orthodox Church, then delivered an impassioned speech reminding those gathered of the sacrifices made by the city’s inhabitants as they overthrew the Turkish “occupation” a century before, during the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913. He emphasized the inextricable connection between the Greek Orthodox Church, the Greek nation, and the Greek Christian identity of Salonica.

Salonica’s new mayor, Yiannis Boutaris, a soft-spoken 70-year-old, then began his speech about the city’s glorious history. Within moments, two Greek Orthodox priests charged him, shouting fiery denunciations. “Anathema!” one of them cried, before being wrestled away from the scene by police. Others in the crowd sympathized with the disgruntled priests. “Go away, Boutaris!” one woman shouted. The reason for their anger was clear: Boutaris avoids hardline, exclusivist, nationalist rhetoric. He envisions a very different future from those on the right, one that takes into account the fact that not only Christians, but also Muslims and Jews, called the city home for centuries. “We cannot look into the future without knowing the past,” Boutaris recently declared to The Jerusalem Post. Recognizing that Jews once constituted half of Salonica’s population, he continued, “Not for nothing was it called the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans.'” He added: “And it could be that again.”

Jews have lived in Salonica since antiquity. The apostle Paul preached to Greek-speaking Jews there in the 1st century, and there has been a more or less continuous Jewish presence in the city ever since. The Jewish community blossomed in the 16th century, when Salonica became a major refuge for Jews exiled from Spain and Portugal. Under Ottoman rule, Sephardic Jews added to the one Ashkenazi synagogue by establishing three dozen more based upon their places of origin throughout the Iberian Peninsula, as well as Italy and North Africa. Salonica became a center not  only of rabbinic learning, but also of early modern Hebrew publishing. It was the birthplace of Solomon Alkabetz, the author of the Sabbath prayer, Lecha Dodi, and the city where Joseph Karo prepared his famous code of Jewish law, Beit Yosef. By the mid-16th century, Jews constituted half of the city’s residents and formed one of the largest Jewish communities in the early modern world. The image of the 16th-century golden age of Salonica as a center of Jewish refuge and Jewish learning is conjured by the expression, “the Jerusalem of the Balkans.”

only of rabbinic learning, but also of early modern Hebrew publishing. It was the birthplace of Solomon Alkabetz, the author of the Sabbath prayer, Lecha Dodi, and the city where Joseph Karo prepared his famous code of Jewish law, Beit Yosef. By the mid-16th century, Jews constituted half of the city’s residents and formed one of the largest Jewish communities in the early modern world. The image of the 16th-century golden age of Salonica as a center of Jewish refuge and Jewish learning is conjured by the expression, “the Jerusalem of the Balkans.”

There is another, more modern, image of the city that is evoked by this designation. The second half of the 19th century saw Salonica emerge once again as a regional capital—a cosmopolitan metropolis and an economic center at the crossroads of Europe and the Middle East. The Paris—based Alliance Israélite Universelle equipped a new generation of Jewish students with modern education and vocational skills. The publication of Ladino newspapers flourished, as did Ladino theater. The Jews of Salonica ranged from major industrialists who established the city’s first flour mill, distillery, and brick and tobacco factories, to stevedores at the port, fisherman, tobacco laborers, bootblacks, lawyers, teachers, customs officials, seamstresses, rabbis, pumpkin seed sellers, lemonade vendors, and halva makers. In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in the city and declared it “the only Jewish labor city in the world.” The role of Jews was so great that the port and virtually the entire city closed on Saturday in observance of Shabbat. At the turn of the century, Jews were the demographically dominant element in the population, comprising as many as eighty or ninety thousand of the city’s one hundred and seventy thousand residents. Indeed, in 1912, as the Ottoman Empire was collapsing, leading Jewish merchants in the city advocated turning their prosperous “Jerusalem of the Balkans” into an autonomous Jewish city-state.

flour mill, distillery, and brick and tobacco factories, to stevedores at the port, fisherman, tobacco laborers, bootblacks, lawyers, teachers, customs officials, seamstresses, rabbis, pumpkin seed sellers, lemonade vendors, and halva makers. In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in the city and declared it “the only Jewish labor city in the world.” The role of Jews was so great that the port and virtually the entire city closed on Saturday in observance of Shabbat. At the turn of the century, Jews were the demographically dominant element in the population, comprising as many as eighty or ninety thousand of the city’s one hundred and seventy thousand residents. Indeed, in 1912, as the Ottoman Empire was collapsing, leading Jewish merchants in the city advocated turning their prosperous “Jerusalem of the Balkans” into an autonomous Jewish city-state.

Salonica was instead incorporated into the Greek nation-state. Over the following three decades the city’s socioeconomic complexion changed. A major fire in 1917 destroyed the city center, leaving most of the Jewish population homeless. In the 1920s the arrival of more than a hundred thousand Greek Christian refugees from Turkey changed the social dynamics of the city, and in the 1920s and ’30s Jews faced increasing prejudice. Nonetheless, the Jewish Community continued to operate Jewish schools, a rabbinical court, and over twenty philanthropic institutions; Ladino cultural productivity continued while the acquisition of Greek culture rose; and younger Jews started to feel at home in Greece. When the Nazi occupation forces arrived in April 1941, fifty thousand Jews remained in the city. Almost all were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943 and murdered there.

After World War II, Salonica was reduced to a border city of secondary significance and defended Greece against the Communist threat. Reflecting these anxieties, Salonica’s administration for the past sixty years was particularly conservative. The open-mindedness of Mayor Boutaris, an aging, tattooed politician and former winemaker who recalls his youthful love affair with a Jewish girl, starkly contrasts with the narrow nationalism of his political predecessors. It’s also at odds with the chauvinism of church leaders such as Bishop Anthimos and many of the city’s residents. But one thing is evident: although for decades a taboo topic, the Jewish presence in (and absence from) Salonica and Greece is increasingly entering public discourse in ways that are both promising and troubling.

As in other parts of Europe, the economic crisis has been a boon for the nationalist right and has led to a resurgence of anti-Semitic rhetoric. The ultra-right-wing, anti-austerity, anti-immigrant, anti-Muslim, anti-Semitic Golden Dawn party now holds eighteen of the three hundred seats in Parliament. “There were no ovens. This is a lie,” proclaimed the head of Golden Dawn, Nikolaos Michaloliakos, on Greek television in May. “There were no gas chambers either,” he added. He follows syndicated journalist Costas Plevris, whom the Jewish communities of Greece brought to court in 2007 for his repeated statements denying the Holocaust and for inciting anti-Semitic violence. The superior court acquitted Plevris—Holocaust denial is protected by freedom of speech in Greece. One judge endorsed Plevris’ animosity against the Jews, whom she agreed sought to control the world by nefarious means. Plevris has since countersued for libel and several Jewish leaders await trail. Moreover, in October 2012, Ilias Kasidiaris, an MP representing Golden Dawn, read a passage from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion aloud during a parliament meeting without comment or censure from his colleagues. Although these statements are extraordinary, the acceptability of anti-Semitic discourse in everyday Greek life, despite—or perhaps because of—the fact that Greece’s Jewish population now numbers only around five thousand, is startling.

in 2007 for his repeated statements denying the Holocaust and for inciting anti-Semitic violence. The superior court acquitted Plevris—Holocaust denial is protected by freedom of speech in Greece. One judge endorsed Plevris’ animosity against the Jews, whom she agreed sought to control the world by nefarious means. Plevris has since countersued for libel and several Jewish leaders await trail. Moreover, in October 2012, Ilias Kasidiaris, an MP representing Golden Dawn, read a passage from the Protocols of the Elders of Zion aloud during a parliament meeting without comment or censure from his colleagues. Although these statements are extraordinary, the acceptability of anti-Semitic discourse in everyday Greek life, despite—or perhaps because of—the fact that Greece’s Jewish population now numbers only around five thousand, is startling.

For his part, Boutaris has publicly stated that most of the Golden Dawn’s leaders ought to be jailed. Rather than closing the borders, he wants to open them—at least for foreign investment—in the hope of stimulating the city’s rejuvenation. To this end, he has actively sought to strengthen relations with Turkey and Israel by inviting Muslims and Jews to return, as “heritage tourists,” back to a city their communities once populated. To some extent, this has worked. Both Turkish and Israeli tourism are on the rise. Regular flights now link Tel Aviv and Salonica, a sign of Greek-Israeli rapprochement. Although one of the first countries to support the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, prior to the Balfour Declaration in 1917, Greece became the last European Union country to officially recognize the state of Israel—in 1991. Since relations between Turkey and Israel cooled off following the Mavi Marmara flotilla to Gaza in 2010, Greek-Israeli relations have been “upgraded.”

Boutaris included Hasdai Capon, a local Jewish leader, on his ticket. When they won, he became the first Jew elected to the city council since 1936. He is now vice mayor for economic management and has significantly cut the city’s debt. Nonetheless, signs of the economic crisis are widespread: abandoned shops along the main drag, Tsimiski Street, and extensive graffiti. I had a chance encounter with my neighborhood baker, whose shop I frequented when I lived in the city several years ago. He had lost his bakery and was selling koulouria (Greek breads) out of a sack on the street. Garbage collectors were on strike one day, buses another, taxi drivers another, and airport workers yet another.

In contrast to Golden Dawn’s Holocaust denial, Boutaris is the first mayor of the city interested in public Holocaust commemoration. Before, there was mostly silence. The increased, open discussion of Jewish presence and of the Holocaust was made clear to me as soon as I arrived in October. My taxi driver, who was pleased by my decent Greek, asked me, after he discovered I was Jewish, if I had returned to take back my family’s house. This question was not idle. The few survivors who returned to Salonica after the war found Christians living in their homes. The restitution of the more than ten thousand “abandoned” Jewish properties remains unresolved today.

I arrived at Hotel Amalia, in the city center, on Ermou Street, adjacent to the Modiano market, one of the few sites in Salonica still bearing a Jewish name. Strangely, the first language I heard was Hebrew: Several older Israeli tourists were chatting in front of the hotel. We spoke in Hebrew and then Ladino. Their family had also lived in Salonica before the war, and, just as Mayor Boutaris had hoped, they wanted to see what had become of it.

I met two friends for dinner and a late-night stroll through the city center. In their thirties, these friends come from families of Greek Holocaust survivors and are among the relatively few Jews who remain in Salonica today (perhaps one thousand in a population of one million). Yet those who remain, especially these friends and other young Jews like them, have a deep interest in the past of their city and the traces that remain. The Holocaust occupies the center of the story, but to the remembrance of destruction must also be added the recognition of the life that once was. They take me on a tour of Jewish buildings, surviving inscriptions, and sites where Jewish communal institutions once stood.

The conference I had come to attend was called “Thessaloniki: A City in Transition, 1912-2012.” The official publicity materials avoided nationalist rhetoric and did not refer to the “occupation” of the city by “the Turks,” nor to its “liberation” by the Greeks in 1912. The selection of Mark Mazower, a history professor at Columbia University, to give the keynote address revealed the conference organizers’ relatively open approach to the city’s past. Mazower’s 2005 book Salonica, City of Ghosts placed the city and its multicultural past on the international scholarly map. The Greek translation became a bestseller and compelled the city’s residents to confront its full history head-on for the first time.

But while it became apparent at the conference that certain controversial aspects of the city’s past could be discussed openly, others remained cloaked in silence. The deportation of Salonica’s Jews by the Nazis was an uncontested fact. But the centuries-long history of the Jews of the city was virtually reduced to that moment. Jews entered the narrative only in 1943 with their deportation and murder in foreign lands. Under the city’s previous administration in 2008, the municipality rejected a proposal that Salonica join the Association of Martyr Cities, a network of ninety locales throughout the country that commemorates the “Greek holocausts” of civilians who died in the struggle against the 1941-1944 occupation. Salonica’s City Council denied the proposal on two remarkable accounts: that the extermination of the Jews took place outside of Greece and that Jews have lived in Thessaloniki only since 1492.

As pointed out by the antonymous blogger “Abravanel,” one of the few who actively reports on Jewish issues in Greece, the second point was particularly disheartening since it denies the documented presence of Jews in the city for two thousand years, prior to the expulsion from Spain. It is also an ironic argument given that Salonica’s Jews are likely among the few present-day residents whose ancestors have lived in the city for more than a century. Most of the city’s Greek Orthodox residents arrived in the 20th century, principally as refugees from Turkey.

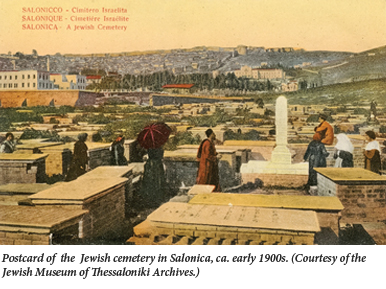

With Boutaris as mayor, unprecedented discussions are underway to transform the recent, modest, and slightly equivocal Holocaust Memorial. It was erected in 1997 when Salonica was named “the Cultural Capital of Europe” by the European Union and moved to a more central location in 2006 when Israeli President Moshe Katsav visited. Now it may become something more substantial: a  listing of names, in stone, of all of the Salonican victims of the Nazis. There is a painful irony in the concept of a future monumental tombstone for Salonica’s Jews since the city’s once vast Jewish cemetery, where actual tombstones once stood, completely vanished during the Nazi occupation. The story of the destruction of the Jewish cemetery—once the largest in Europe—remains largely shrouded in silence. It covered the space of eighty football fields and housed hundreds of thousands of graves, including those of famed personalities, dating back to the late 15th century-including the daughters of Joseph Karo, and the acclaimed Converso physician, Amatus Lusitanus.

listing of names, in stone, of all of the Salonican victims of the Nazis. There is a painful irony in the concept of a future monumental tombstone for Salonica’s Jews since the city’s once vast Jewish cemetery, where actual tombstones once stood, completely vanished during the Nazi occupation. The story of the destruction of the Jewish cemetery—once the largest in Europe—remains largely shrouded in silence. It covered the space of eighty football fields and housed hundreds of thousands of graves, including those of famed personalities, dating back to the late 15th century-including the daughters of Joseph Karo, and the acclaimed Converso physician, Amatus Lusitanus.

The painful truth is that the municipality and the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki benefitted from the Nazi occupation to implement a plan, under development for more than a decade, to expropriate the Jewish cemetery and expand the campus of the university on top of it. At the municipality’s expense, five hundred workers with pickaxes laid waste to the Jewish cemetery of Salonica in December 1942. The university was built in its place. Today, no marker or sign indicates that the former Jewish cemetery of Salonica lay below the university campus. Given the admirable sentiments animating the conference and the widespread willingness to speak about the Nazi deportations, it was alarming to listen to a paper presented by a professor from the university about the expansion of the campus since the 1930s. He never mentioned what had previously existed on the very land on upon which that expansion occurred.

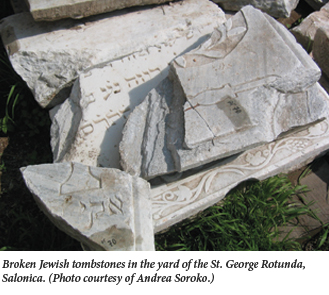

Despite this silence, traces of the Jewish cemetery of Salonica have been in the news. Before the economic crisis hit, in 2008, the municipality began work on a subway system. Controversy erupted amidst the construction of the stop for the university. Remains of the Jewish cemetery had been unearthed. Abravanel suggested the future train stop be named “The Jewish Cemetery” rather than “The University,” or that relevant archaeological finds be put on permanent display. Neither that suggestion nor the construction of the subway more generally has progressed very far. Just a few months ago, in December 2012, a report that Salonica’s police discovered over six hundred fragments of Jewish tombstones in the western corner of the city made international news. The Jewish community gained possession of the fragments and transferred them to the postwar Jewish cemetery, located in the suburb of Stavroupolis. This postwar cemetery has become, in effect, a graveyard for tombstones.

That the discovery, if it can be called that, of the tombstone fragments should be deemed newsworthy today is also remarkable considering the extent to which traces of them can be found in every part of the city. At the time of the cemetery’s destruction, the municipality, the university, churches, and local residents appropriated the marble headstones for construction throughout the city, to pave roads, line latrines, and build courtyards. The Nazis also used them to build a swimming pool. A few tombstones with Hebrew inscriptions can still be seen on the university campus. Others can be seen today stacked in church courtyards, behind the St. George Rotunda, and built into various structures, such as the floor of the St. Demetrius church, the central Navarinou Square, and elsewhere.

Last year, at the urging of the Jewish community of Salonica, the rector of the university began speaking about the possibility of creating a monument to the Jewish cemetery—which, as the local Greek press reported, quoting the rector’s convenient use of passive voice, “was destroyed due to the conditions of the German occupation.” Art faculty from Tel Aviv University came for a visit to discuss creating a commemorative sculpture. In exchange, a piece of artwork from the University of Salonica would be installed at Tel Aviv University. The proposed arrangement, while unprecedented, is also remarkable because the responsibility to commemorate the destruction of the Jewish cemetery would lie with Israelis and only as a part of a quid pro quo arrangement. While a seemingly genuine endeavor, such a proposal may push Aristotle University and the city further away from coming to terms with their past.

Acknowledging the history of the Jewish cemetery in Salonica may be more difficult than commemorating the deportation of the city’s Jews for another reason. The present Holocaust monument commemorates Jewish death on foreign soil during a single year, 1943. A monument to the city’s burial ground would require a more robust recognition of Jewish life in Salonica for at least five hundred—if not two thousand—years. It would compel the city to confront its ghosts.

The aspiration to recognize Jewish life in the city had animated a cohort of Jewish intellectuals in interwar Salonica. They sought to combat the initial attempt by the municipality to expropriate the Jewish cemetery for the use of the university. The Jewish tombs, the local Ladino press proclaimed, were piedras ke avlan, “stones that speak,” stones that told the story of the Jews in the city, of their contributions to the city, and of the city itself. For these reasons, Jewish intellectuals argued, the Jewish cemetery ought to be preserved as a monument of Salonican and Greek patrimony. Their argument did not succeed then. One wonders whether it could now.

Over dinner during the conference, I asked a senior Greek colleague why more Greek scholars did not study the history of Jews in Salonica. At first he suggested to me that it was a problem of language: we don’t know Ladino. But in Greece, if a graduate student really wanted to study French history, wouldn’t he or she learn French? He answered by telling me that his parents, Greek Orthodox Christians, attended school during World War II. One day the Jews did not show up to school. No one cried, no one mourned, and there were no public displays of grief. This, he said, is why more Greek scholars do not learn Ladino and do not write about Jewish history.

But perhaps this, too, is changing. The first to write about Jewish history in Salonica were Salonican Jews themselves. Picking up where interwar Salonican Jewish historians such as Joseph Nehama, Michael Molho, and Isaac Emmanuel left off, scholars such as Rena Molho reinstated Jews into the narrative of Salonica and Greece in the 1980s. Building upon these earlier efforts, in 2005, several local intellectuals, including both Jews and Christians, formed The Group for the Study of the History of the Jews of Greece, established a regular seminar at the University of Macedonia (across the street from the Aristotle University) and co-hosted a number of conferences. Up-and-coming non-Jewish scholars have also spearheaded an effort to increase accessibility to sources about Jewish history in Greece. In an unprecedented move at the most recent Holocaust commemoration on January 27, the new minister for Macedonia and Thrace publicly acknowledged Salonica not only as the city of Aristotle, but also of Solomon Alkabetz.

Although its membership is less than two percent of its prewar population, the Jewish Community of Thessaloniki persists under the leadership of its president, David Saltiel. Of the nearly sixty synagogues operating in the city on the eve of the war, only one still stands today: the Monastirioton Synagogue, established by Jews who fled their native Yugoslavia in the 1920s. During the war, it was requisitioned by the Red Cross and thus survived. The Jewish Community uses it today only for the High Holidays and major life cycle events, such as weddings. On the other end of town, one of the only other prewar Jewish buildings still standing is the Matanoth Laevionim, which continued to function as the Jewish soup kitchen during the Nazi occupation. My great-uncle served on its council before being deported to Auschwitz along with his wife and two children, where they perished. Today, the building of the soup kitchen functions as a Jewish communal school with over forty students. It operates with the help of foreign assistance, in particular that of the American Jewish Committee.

The religious leadership also comes from abroad, from Israel, and some of the locals lament the loss of the distinctive Salonican traditions. During my visit, I met one of the last of the Salonican Jews intimately familiar with the distinctive liturgy and melodies—the octogenarian Davico Saltiel. We spoke for four hours, in Ladino, about Jewish life in the city before and after the war. He learned the ways of the Salonican traditions from Leon Halegua, the last Salonican-born rabbi of the city who died more than twenty years ago. Saltiel fears that the liturgy of Salonican Jewry will be lost when he dies. He may be right. Fortunately, he has released an album of popular Judeo-Spanish songs that preserve aspects of the community’s rich folk tradition.

The primary site dedicated to the preservation of “Jewish Salonica” is the Jewish Museum of Thessaloniki, which serves as the main public face of the Jewish community. Government officials and foreign diplomats number among the more than four thousand annual visitors. Dedicated to the more than two thousand years of Jewish presence in the city, the Jewish Museum has curated several important exhibitions since it opened in 2003. Yet the museum begins with death—not the Holocaust itself, but rather with the Jewish cemetery. Without hinting at the possibility that someone other than the Nazis may have initiated its destruction, the Jewish Museum opens into a hallway lined with Jewish tombstones salvaged from the cemetery.

My Greek-Jewish friends, who guided me through the city late at night in search of remnants of the city’s Jewish past, reminded me that despite the overtures of the mayor, the hopes of the leadership of the Jewish community, and the activities of a circle of intellectuals, the broader climate in the city and in the country remains ambivalent. Until the city accepts Jewish presence in Salonica both before and after the Nazi deportations of 1943; acknowledges its role in destroying the most important monument to that presence, the Jewish cemetery; and resolves the question of Jewish properties, efforts to truly remember the Jerusalem of the Balkans will be stymied. In the meantime, as a grandson of Salonica, I hope to help my friends tell their story.

Suggested Reading

Tangled Truly

Letters of ink. Letters of the heart.

When Everything Matters

Bellow on Roth on TV.

Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

What are the conditions for a Jewish intellectual renaissance? Disagreement is one, inconsistency might be another; look at the early Zionists.

Tradition and Invention

If Jews were included in early 20th-century discussions of political communities, it was generally concerning their right to preserve their language and culture, along with other minorities, at a time when empires were being dismantled.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In