Tangled Truly

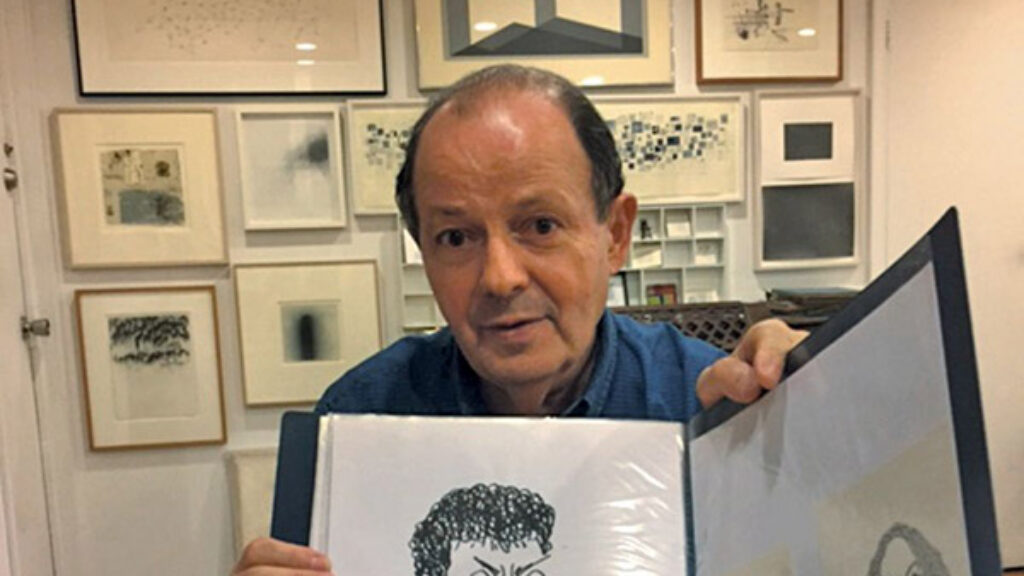

“Drawing’s goyish, / said the cloud,” writes the poet Peter Cole in his new book, Draw Me After. The cloud might be right. Jewishness means being richly weighted with ancient meaning. Drawing promises a fresh start, turning the line wherever the artist chooses, with the blank page an unoccupied Eden. Yet the Jew can look at drawing, and even write about it. Draw Me After features nine drawings by the artist Terry Winters, with a poem by Cole accompanying each image, bridging the gap between the Jewish poet and the non-Jewish artist.

It’s just like Cole to wonder what makes an art form Jewish or not. Born in New Jersey, he has lived in Jerusalem for four decades. His book contains much that is unarguably Jewish: for instance, an extended riff on Kohelet (Ecclesiastes); translations of Yehuda Amichai, Leah Goldberg, and Natan Zach; and an abecedarium devoting a poem to each letter of the Hebrew alphabet. Cole’s epigraph comes from the Zohar Chadash’s comment on the Song of Songs (66c): “Each letter called, saying, / ‘Draw me after you, let us run.’” The chasing is playful, but also fateful. Like few current poets, Cole can be light-handed and somber at once, and full of a vigor stemming from his deep immersion in Hebrew literature.

Cole’s alphabet poems are compact marvels. Consider his sprightly poem about yud—the letter of creation, because it marks the third-person future tense. Yud is a jot that jolts us into something new, and it bends down like a tiny God surveying the work of world-making, which is most remarkable in small things:

In this tradition

smallness stands

tall through all

lending a hand

to creation

And so a squiggle

crowns our scrawl

as eminence bends

down to call

us through duration

The taut internal rhymes are like minute springs powering this little poem, whose course veers from “tradition” to “creation” to “duration”—three terms for Jewish stamina over the centuries, here kept in the air like jugglers’ balls.

Cole plays with the Hebrew words that begin with his chosen letters. Mem is “this angels’ tank of measured listening” (the Merkabah, Ezekiel’s chariot and Israeli tank), nun a “kitelike flame of soul-hovering” (a ner, or candle), and gimel “like / a camel sticks its neck / out for a thing” (gamal means camel). Entranced by the aleph-bet, he makes the letters grounds for fantasy.

Cole’s work, like that of the medieval Jewish poets Shmuel ha-Nagid and Shlomo ibn Gabirol, which he translated in his splendid anthology The Dream of the Poem: Hebrew Poetry from Muslim and Christian Spain, 950–1492, keeps coming back to the letters and spirit of Hebrew and also to his own spiritual tzuris. Kohelet, a crucial source for ha-Nagid, is the book of qualms. In Draw Me After, Cole calls his imitation of Kohelet “From the Qualmist’s Quair.” His verses pulse back and forth, probing everything under the sun:

Look around:

Chance and Time

have at all

again and again

and none know when

theirs will come

like schools of fish

near nets stretched out

or birds at snares

fate has baited,

their days in flight

(click) done.

Cole’s verses snap shut on human hope, while feeling our common plight. At times he adapts

Kohelet with an eye to the haunting King James Version. “Everyone leaves / for the long dwelling,” he writes (the Hebrew has simply beit olam, which in the KJV becomes “long home”),

before the silver

cord is snapped,

before the golden

bowl shatters

and the pitcher’s broken

beside the spring,

and wheels to the cisterns’

waters are crushed,

dust returns

to earth as it was,

breath to the place it

blew through us from.

Cole omits Kohelet’s closing admonition to follow the mitzvot, which was probably added by a pious editor. Instead he asks, about wisdom, “who / could grasp it?”

Draw Me After places Kohelet, the ancient wisdom writer, next to twentieth-century Hebrew poets whose seeming simplicity also yearns after truth—Amichai, Zach, and Goldberg. For these modernists the truth takes sly forms. When Cole translates Goldberg’s spare poem “Late Fragments,” he alludes to a line from Shakespeare’s As You Like It: “The truest poetry is the most feigning.” To feign, to weave a fiction, is Cole’s word for Goldberg’s kazav. Where Goldberg speaks of poetry deploying a lie (sheker), Cole writes “fiction,” since “lie,” unlike the Hebrew sheker, has such a hard edge in English. His poem is less stark than Goldberg’s original, but he is true to her equanimity. She subtly balances the poem she writes with the one she might have written, which is lost to time. “Come . . . come to me, Muse,” the aging poet says, “and lean your whitening / head against mine. // We’ll play with words . . .” Goldberg’s wistfulness has its fine resources, which Cole adeptly carries over from Hebrew to English.

Draw Me After can be fiercely political. The book contains a potent prose poem on the letter quf, where Cole condemns hillside settlers who are:

descending through a slope-stepping prance, fringes trailing—their dance sick with a stiffened faith, wicking and blotching their map of state, like a cancered scan, eating away at its

language and letters, as One yields gun or none or bone . . .

In the face of this corrupt nationalist yearning, Cole is brought down “to sinews of creaking knees, wrestling the gust of a given moment’s giving, like vapor, and strangely grateful.” Cole is mindful that brakha in Biblical Hebrew can mean both blessing and curse, and so “Quf” turns from its bitter cursing of the settlers to a desire for blessing. Here in the stance of prayer, Cole prizes the vapor, the hevel, that Kohelet clutches at.

Cole’s most visible precursors outside of Hebrew sources are James Merrill, May Swenson, and A. R. Ammons, three American poets who play seriously with words, often making sharp epigrams. All three are careful and exploratory. Like Cole, they are wisdom poets, and so prize a resolute compactness. They resist the unbridled, as Cole mostly does too. But at least once in Draw Me After he lets loose, with his barbed and breathless chant “This Pig I,” based on a Leonard Baskin woodcut of a fierce-looking pig. The pig-poet is trussed up by low appetites: “This pig I live with really / does hover over much of / what I do and say,” he writes:

it’s like

a shadow in its knowing how

dark at heart I am in part

it loves the muck I’m often in

the sty and stink of me and my

The poem ends with a ritual injunction: “Pig, poet, thou shalt not eat.” Jewish dietary law reminds the poet of his duty to combat the pig within. In “This Pig I” Cole, mired in baseness and straining to get out, displays a radical self-dissatisfaction—a possible new path for his verse.

“This Pig I” is savagely winning self-satire. But at least one other of Cole’s ekphrastic poems from Draw Me After falls short. In “Look Again,” which evokes Agnes Martin’s paintings, Cole sees a healing balm in Martin’s ethereal wash of colors. Cole’s two-beat lines echo May Swenson, as he marvels how Martin’s abstract canvases make the viewer guess at shapes. “Is it stone / no it’s sky / and now it’s sand / or standing water,” Cole writes. But his wonderment seems too easy. Describing Martin’s serenely minimalist work, Cole turns bland: “it’s an origin / it’s an end / it’s an island / it’s a friend.” This is far too cozy and gentle. Cole is much better when his play has more of an edge, as in his aleph-bet poems, or when he searches with Kohelet through first and last things. He is at heart a poet of worry and restless passion, rather than halcyon comfort.

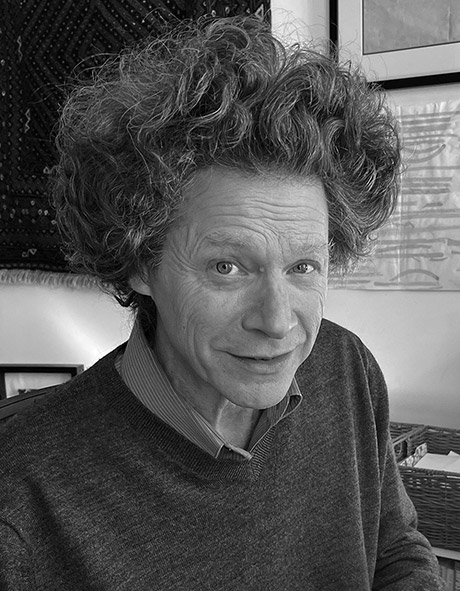

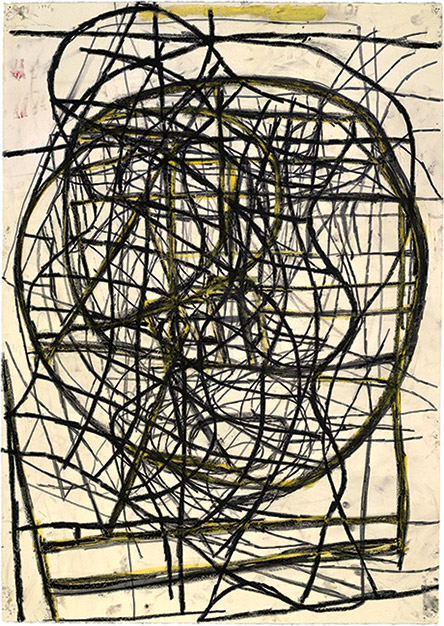

Terry Winters’s restlessness makes him an apt partner for Cole, as well as an unexpected spur for Jewish trains of thought. His lines are thick with ink and tightly woven; they bunch up, cascade, and loop back. Some of the drawings resemble puzzles, while others strive energetically to weave darkness onto white paper.

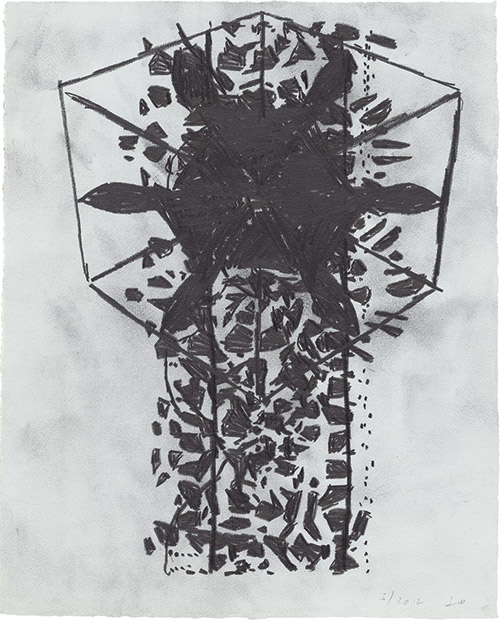

The drawings are a Rorschach test for Cole’s Jewishly-inclined eye. When Cole confronts the dense snarl of lines that Winters puts on paper, he can’t resist adding a Hebraic tinge to what he sees. One of the drawings, he declares, is “a song / of songs tangled truly in our / being,” another “An ark so dark it / glows with its holding.” As he looks at one Winters drawing, Cole strikes a kabbalistic note, detecting “a hardening spark’s / unhidden power.”

Cole writes about a Winters drawing of what looks like a many-petaled, incandescent angel bristling with ink blots. The picture appears to be Winters’s response to the Angelus Novus by Paul Klee that Walter Benjamin owned and treasured. Cole writes:

This dark plant glows with its ground

and grows from a black fire of whiteness—

so boundlessness pulses, nearly in hand.

The letters of the Torah, it is said, are black fire on white fire. At their best, Cole’s fiery poems speak to us like a revelation.

Suggested Reading

Bellow, His Biographers, and the “Quivering Schmucks”

Many authors have passionate readers, but few have drawn as many self-consciously nutty fans as Saul Bellow.

Time and Ink: The Minimalist Devotions of Jacob El Hanani

The idea of a scribe who, like El Hanani, sets to work every day but never produces the same text twice—or never produces a legible text at all—would have appealed to Franz Kafka.

Ink and Blood

Arthur Szyk may well be the only great Jewish artist whose work countless people recognize simply because they have attended a Passover Seder. Less well known are the explicit connections between the Egyptian pharaoh and Hitler that Szyk had embedded in his original version of the haggadah he created in the 1930s.

The Apocryphal Psalms of David 1:15–20

In 1902 Abraham Harkavy published two previously unknown psalms and parts of two others from a manuscript in the Cairo Geniza. They may date back to the Second Temple.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In