POLIN: A Light Unto the Nations

How is it that the largest public building to go up in Poland since that country regained its freedom, the first museum to tell the story of Poland from beginning to end, goes by the name of POLIN? Po lin, or “rest here,” is what the first Jews who arrived in the 10th century are said to have declared. The more official, descriptive name of the shiny new 16,000 square meter building is the Museum of the History of Polish Jews, whose official opening I attended in Warsaw, October 28–30.

The museum began as the brainchild of the director of the Association of the Jewish Historical Institute of Poland, Grażyna Pawlak, who was invited to attend the opening of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1993. What was needed now, she realized, was not another memorial museum in Poland; Poland itself was a Holocaust memorial. What Poland needed, rather, was a museum dedicated to Jewish life. What followed, over the next 21 years, under the adroit leadership of Jerzy Halbersztadt, was a public–private partnership that eventually included the Ministry of Culture and National Heritage, the city of Warsaw, private foundations, individual philanthropists, both Jewish and Christian, the Republic of Germany, and the Kingdom of Norway. A total of $54 million was raised for the construction of the building and another $43 million for the core exhibition, enormous sums anywhere and unprecedented in the new Poland.

The original designers of the museum had drawn up an “Outline of the Historical Program and Master Plan,” but the time for central planning and familiar stories, neatly broken down into historical periods and punctuated by ideological schisms, had long since passed. More pressing than any academic scruples about master narratives was the fact that such an approach couldn’t possibly succeed in speaking to the museum’s prospective visitors, who would include Poles from high-school age to senior citizens, Israelis and Jews from across the globe, casual foreign tourists, and pilgrimage groups to the death camps.

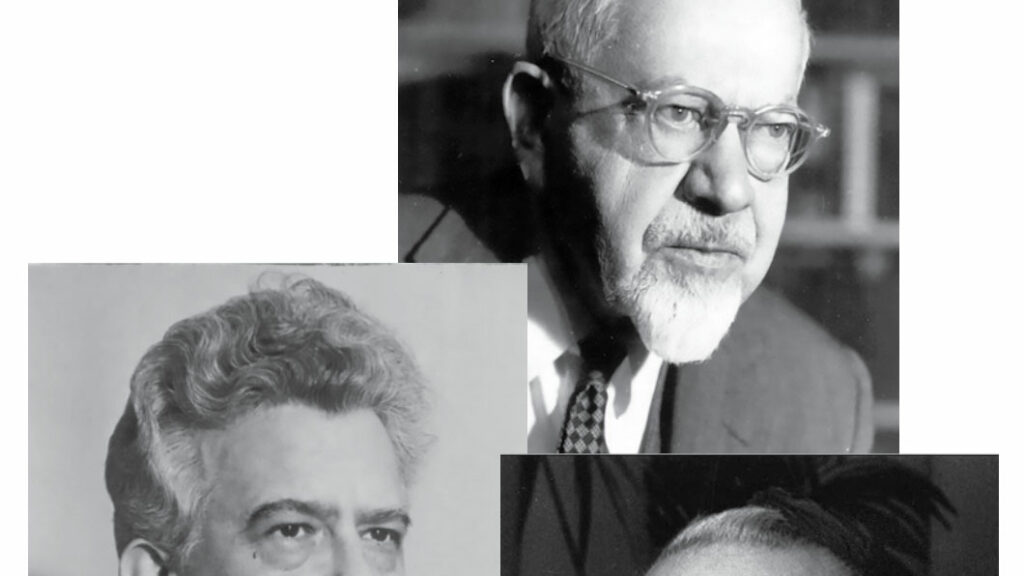

By the time Barbara Kirshenblatt–Gimblett was appointed to head the Academic Team of the Core Exhibition of the POLIN Museum in 2006, she had already redefined the way museums represented the Jewish past. Where once upon a time, pride of place was given to Torah scrolls and breastplates, spice boxes, Kiddush cups, candelabra, Torah pointers, and other sacred paraphernalia of the Jewish faith, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett curated an exhibition for The Jewish Museum of New York called “Fabric of Jewish Life” that focused exclusively on textiles, most of them produced by women. Where Roman Vishniac, on instructions from his employer, had once selected only those photos of Polish Jews that portrayed them as “persecuted, pious and poor” (as she once told a reporter for Ha’aretz), in Image Before My Eyes: A Photographic History of Jewish Life in Poland, 1864–1939, Kirshenblatt–Gimblett produced a counter–album with Lucjan Dobroszycki that stressed the diversity and urbanity of their subjects. And where once, at the New York World’s Fair in 1939, Jews created a Palestine Pavilion to stake a claim for national sovereignty and to generate foreign investment, now, in the 21st century, Kirshenblatt–Gimblett instructed her team to “think Expo” and create a multimedia narrative exhibition that would demonstrate the centrality of Jews to Polish history—to turn their dimly remembered story, she said, into something you can touch, hear, rub, erase, pull out, disassemble, walk through, climb up, get lost in, and, above all, experience from more than one perspective.

Kirshenblatt–Gimblett’s qualifications to curate POLIN went beyond the impressive but predictable CV accomplishments of a museum or academic superstar (currently, she is a university professor and professor of performance studies in the Tisch School of the Arts at NYU). She grew up in the Orthodox Jewish community of Toronto with parents who had been born in Poland. As a teenager, she used to walk to the Royal Ontario Museum on Saturdays (admission was free), exploring one floor a week: native Canadians, totem poles, geology, Greek vases, and more. At the age of 18, the museum hired her. Almost half a century later, just before she took up the position at POLIN, she and her father, Mayer Kirshenblatt, completed They Called Me Mayer July: Painted Memories of a Jewish Childhood in Poland before the Holocaust, for which she had written the text. There is an obvious continuity between the “Mayer July” project (which also ended up including a documentary film) and the core exhibition of POLIN. Both are attempts to depict the Polish Jewish past vividly and unsentimentally, but there seem to me to be important differences too. Whereas the “Mayer July” project was a touching act of filial love and a frank commemoration of an almost vanished family history, Kirshenblatt–Gimblett was determined to produce something more open–ended for the museum.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, who is referred to in alternating tones of affection and awe by her colleagues as “BKG,” worked her team very hard, and there were, apparently, many defections. Historians, who tend to think in footnotes, had a hard time finding striking visual correlatives for the latest advances in Polish–Jewish scholarship. Surrounded by the curators, collaborators, experts, and consultants of a gallery, Kirshenblatt-Gimblett reportedly would sometimes interrupt the proceedings by feigning a yawn and, speaking for the ordinary museum–goer, say, “BO–RING!”

The designers, Event Communications from the UK and Nizio Design International, experts in museum design but novices in Jewish history, were also difficult for the academics to please. (“So tell me, Professor Assaf,” they would ask, “what is Hasidism?”) Professor Samuel Kassow of Trinity College, whose main portfolio was the interwar period (the so–called Second Polish Republic), made 25 trips to Warsaw during the planning of the museum. Somewhere along the way Kirshenblatt–Gimblett became a Polish citizen, learned to speak Polish, and started an active blog about her everyday life. Her voice informs the handsome, richly illustrated 430–page catalogue to the core exhibition, just as her vision, spelled out in a brilliant introduction called “Theater of History,” animates the whole museum.

This is a theater in eight acts, or galleries, set up in such a way that one can go from the forest to the gift shop in 90 minutes. The painted forest is the symbolic backdrop for the arrival of those first Jewish exiles who gave the country and the museum its Jewish name. It is theater, because instead of being presented with original artifacts behind glass partitions, the visitor finds interactive displays, scale models, visual cues, and sound effects every step of the way. Thus a display of Jewish tombstones is actually a screen image of a dozen graves, each of which will fill the screen when touched. A Hebrew inscription will gradually appear when you rub it, and a final tap of the screen will miraculously produce a translation of the epitaph into Polish or English.

Gallery Three, called (with tongue slightly in cheek) “Paradisus Judaeorum, 1569–1648,” opens with a huge map of the newly created Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. It took two teams of historians to create a map of the 1,200 Jewish communities in an empire that stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea, and it took Adriane Leveen, who teaches Bible at Hebrew Union College–Jewish Institute of Religion in Manhattan, less than eight seconds to locate Slonim, her ancestral home.

About a half hour later, the tour I had joined was gathered “On the Jewish Street,” on the side dedicated to Jewish politics between the two world wars. A distinguished colleague of liberal bent was helping another American negotiate the “Polish–Jewish Politics” game. The three main contenders were the Labor Zionist Poalei Zion, the ultra–Orthodox Agudas Yisroel, and the Jewish Labor Bund. At each step the player was asked a series of multiple–choice questions—whether to stay or to emigrate, to choose Palestine, Western Europe, or the Americas, to support the Polish right-wing bloc or the left, to speak and educate one’s children in Polish, Yiddish, or Hebrew—and to everyone’s amazement, by a computer–generated process of elimination, the player’s best bet was to vote for Agudas Yisroel.

Each gallery has its own set of props; everything is different from room to room, from the fonts (both Latin and Hebrew alphabets) to the seats (chairs, pews, stools, benches, armchairs, or barrels). Space quite literally defines the historical moment, whether it’s the market of a Jewish town flanked by a tavern, a Jewish home, and a Catholic church; a railway station (with very plush seating) situated in the heart of the industrialized Kingdom of Poland; or a reconstruction of pre-war cobblestoned Zamenhofa Street in Warsaw with a dizzying array of competing political movements on one side and three stellar groups of Jewish writers on the other.

Precisely because each gallery is so laden with the latest in museum technology, so variegated, so full of artifice, it came as something of a relief to enter the reconstructed synagogue of Gwoździec, Galicia, with its exquisite painted ceiling and timber-framed roof. The first I ever heard of such wooden synagogues was from a book of diagrams, scale drawings, sketches, and black–and–white field photographs published by the Institute of Polish Architecture of the Polytechnic of Warsaw in 1959. In 2003, the architectural historian Thomas Hubka published Resplendent Synagogue: Architecture and Worship in an Eighteenth-Century Polish Community (reviewed in the Winter 2012 issue of this magazine by David Gelernter). Hubka’s book inspired Rick and Laura Brown, the co–founders of the Handshouse Studio in Massachusetts, to spearhead an international team of historians, architects, artisans, students, and artists specializing in traditional woodwork and polychrome painting, who spent three years erecting a replica before transporting it to its permanent home—in Gallery Four.

“Resplendent” is an apt description for the synagogue interior, which is covered from floor to ceiling with snippets of Hebrew liturgy, zodiac signs, messianic symbols, and a fabulous array of animals, both real and mythological, all in vibrant, living color. Reproductions of this interior, in fact, are the first thing you see when you enter the terminal at Warsaw International Airport, and they were reproduced all around Warsaw the week I was there. One might compare the Gwoździec reproduction to the Globe Theatre, lovingly restored in present–day London as the preferred site for performances of Shakespeare, though, it must be granted, no one now prays in this synagogue.

From Gallery Four, “The Jewish Town,” through “Encounters with Modernity” to “On the Jewish Street,” the permanent exhibit takes the visitor to the penultimate story-space, “Holocaust.” We see film footage of the German blitzkrieg, the physical space becomes angular and more constricting, and we enter the Warsaw Ghetto (which fittingly stands here for the 660 ghettos that the Nazis constructed in Poland). This gallery, curated by two Polish historians, Barbara Engelking and Jacek Leociak, focuses on daily life in the ghetto. It is based on the ghetto archive heroically compiled by the historian Emanuel Ringelblum and his Oyneg Shabes group, which they buried in metal boxes and milk cans that were unearthed after the war. (One of the milk cans is on display at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington.) The gallery simulates the ghetto’s main landmark: a wooden bridge that connected the large and small ghettos. From the bridge one sees what ghetto–dwellers saw when they looked across into the Aryan side of the city. It is also from there that one descends the ghetto staircase, street by street, all of which eventually lead to the Umschlagplatz, the collection point for the trains to Treblinka. Stepping back from the core exhibition as a whole, one can say that the 1,200 Jewish settlements large and small that were once scattered over the vast Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth have been reduced to one, and then to none.

There are, however, many sources of light that penetrate the doom, from the sunlight streaming through the massive glass windows at the museum’s entrance to the tower of light that streams down upon the last installation, comprising the photographs and recorded voices of contemporary Polish Jewry. “The story neither begins nor ends with the Holocaust,” Kirshenblatt–Gimblett emphatically warns us in her introduction. The Jews of Poland did not live their lives, she insists, “on the brink of destruction,” and the museum’s historical timeline resists such teleology. Kirshenblatt–Gimblett likens the core exhibition to a documentary without a voice–over.

For the opposite approach, the interested viewer need look no further than “Letters from Afar,” a video art exhibition by the Hungarian Jewish filmmaker Péter Forgács in collaboration with the musical group The Klezmatics, commissioned, as it happens, by POLIN along with YIVO and currently showing at the Museum of the City of New York. The exhibit ominously speeds up, slows down, freezes, and juxtaposes Jewish home movies taken in Poland in the 1920s and 1930s. “We know ahead of time,” Joanna Andrysiak explained in the exhibition catalogue, “that the innocent victim will fall into the hands of the killer.” Invoking Hitchcock, Forgács has likened the pre-war Europe of his subjects to a crime scene.

A light also appears unexpectedly at the end of an animated short film that takes us through a day in the life of the famed Volozhin Yeshiva. This story does have a voice–over, based on the memoirs of students and visitors such as Yehuda Leib Don Yichye, who arrived at the Etz Chaim Yeshiva in Volozhin in 1888 at the age of 19. Yehuda Leib describes being immediately awestruck by the sight of the one–story white yeshiva building with its many windows.

The film, masterminded by the museum’s creative director for media, Arkadiusz Dybel, employs the new technique of painted animation. He recruited actors from Poland and the United States, who were filmed against a neutral green screen, then integrated into computer–generated settings and sequences. It was an inspired idea. Although the building of the Etz Chaim Yeshiva still exists in Belarus, there is almost no visual documentation of what went on inside this famous yeshiva or the many others it inspired. Volozhin, founded in 1803, was a radically new type of talmudic academy, whose goal was not to train young men for the rabbinate so much as to train them in an analytic mode of thinking, a revolution in Jewish religious consciousness that is exceedingly difficult to convey on screen, especially with only four minutes and 47 seconds to spare before the visitor must move on to the next installation.

As the hour hand moves rapidly through its 24–hour cycle, we see the life of the yeshiva through the dreamy eyes of the contemporary beholder. A roomful of young men rise in unison as the rosh yeshiva enters, their look of reverence as he expounds on some fine point of halakha. But it’s growing dark, and the numbers inside the yeshiva are thinning, leaving one solitary student. Reminiscent of the figure in Bialik’s famous poem “Ha-matmid,” he is bent over the Talmud. When he starts to nod off, he pours water over his feet just as the Vilna Gaon, whose student Reb Hayyim founded the yeshiva, is said to have done. But it’s really getting late, and the visitor must also be on his or her way. In the final frame the light emanating from the student’s candle seems to be the only source of light in all of Volozhin. This quasi–cartoon is brilliant metonymic history, history–writ–small. One quibble: The actors appear to me a bit too strapping for yeshiva bochrim described by 19th–century writers.

Perhaps the medium is also the message here. Whereas the modern yeshiva produced a new intellectual elite and a newly individualistic model of religious leadership, Hasidism, the last major trend of Jewish mysticism, became a mass movement within a half–century of the death of its legendary founder, the Ba’al Shem Tov. Rather than a single narrative film, the museum chooses to represent Hasidism with sequential films about the rapid extension of the movement, maps, Hasidic melodies, a comic adapted from the hagiographic classic Shivhei ha-Besht (In Praise of the Ba’al Shem Tov), an interactive game based on the petitionary notes called kvitlekh, and other fun stuff. The Hasidic court is represented here as noisy, dense, and detailed. The yeshiva is lyrical, spare, and monastic.

I appreciated the different rhythms, the choreography of the core exhibition, alternating between the big picture and a more intimate, individualized perspective. I also came to appreciate how the same exhibition could take on very different meanings for its different viewers. Take, for example, the so–called “Royal Cake Installation,” where, suspended in midair but tilted at an angle, there are three oversized oil paintings of the absolute monarchs who carved up the cake of Poland at the end of the 18th century: King Frederick II of Prussia in full military regalia, Joseph II of Austria with his scrawny white–stocking feet sprawled over the throne, and a zaftig Russian empress Catherine II in a voluminous gown. As soon as I saw them, I burst out in appreciative laughter, reminded of all those other museums with rooms full of paintings glorifying kings, queens, and conquests. The “Royal Cake Installation” seemed to me to commemorate the hubris of temporal rulers who came and went. For the Polish visitor, it might suggest something else entirely: that the Jewish narrative of Poland is not a national history of battles lost and won, but rather the story of merchants, tavern keepers, estate managers, scholars, students, industrialists, journalists, beauty queens, revolutionaries, and, above all, the covenantal communities—Krakow, Poznań, Vilna, Warsaw, Wrocław, Zamość—where they lived and thrived.

As plays go, BKG’s Theater of History is not a Broadway musical. There is no feel–good finale. It’s a thousand years of Polish–Jewish history, from the first Jewish settlement to the Solidarity movement and the collapse of communism. The last quarter of a century is left out. Then again, the sequel is all around you: in whatever’s playing in the 480–seat auditorium or in either of the two screening and multimedia rooms; in the Education Center and the Resource Center with their youthful and knowledgeable staff; in what Kirshenblatt–Gimblett calls a safe zone for Jewish–Polish discussion “beyond fear and shame,” where all questions and controversies are on the table.

If POLIN is Poland’s gift to the Jews, it is also the Jews’ gift to Poland. Cynics will say that it is too little, too late, which is, of course, true, but also irrelevant. In his remarks at the opening ceremony Bronisław Komorowski, the president of the Republic of Poland, declared that “it is impossible to understand the history of Poland without knowledge of the history of Polish Jews. It is equally impossible to understand the history of Jews without knowledge of Polish history.”

He also noted that “Polish Jews played a major role in the building of the State of Israel. Indeed, nearly half of all MPs in the first Knesset spoke Polish.” For President Komorowski, as for the two other elected officials seated at the dais—the minister of culture and national heritage and the mayor of Warsaw—how one welcomes the Jews, integrates their story into one’s collective memory, and relates to the state that they have created are true measures of tolerance, honor, and, above all, freedom. Just as the Solidarity movement made the reclamation of the Jewish past part of its struggle, so the opening of the POLIN Museum helps to mark Poland’s enormous achievement as a stable Western democracy. Poland has become a beacon to its neighbors in part by embracing its Jewish past.

Designed by the Finnish architect Rainer Mahlamäki, the building is rendered in a curved, flowing sandstone–like material, which was then encased in a gleaming façade of glass. The exterior is subtly clad with glass fins on which the word Polin is written in Hebrew and Latin letters. The building is set at a respectful distance from the Warsaw Ghetto Monument, whose shape it subtly imitates. Both the monument and the museum stand on sacred ground, at the heart of the former ghetto and the site of its death throes. “To set a glass building on a site of genocide,” Kirshenblatt–Gimblett writes in her introduction, “is a strong statement; indeed, it is an expression of hope in the face of tragedy.” There were times during the opening day when the whole museum was ablaze with light.

The opening ceremony was held on the side of the museum that faces the memorial to the Warsaw Ghetto, and the ceremony began, as befits a state occasion, with President Komorowski and Israeli President Reuven Rivlin lighting the memorial torch at the base of the monument. That night, when I joined a thousand or so young Poles at the public klezmer concert and choir performance in Yiddish and in Polish, I could see the reflection of the flame in the glass. Since Jewish youth routinely come to Poland for the first time on the March of the Living, a pilgrimage to the major death camps, there will now be a light at the end of their journey, a museum geared specifically to the interactive habits of their heart that tells of the Jews who lived before, during, and after.

Overwhelmed by the first day’s events (and perhaps also jet lag), I got a bit lost on my walk back to the hotel and asked a 30–something woman walking her little dog for directions. She answered me in fluent English, and we got to talking about the new museum, which she hoped to visit soon. She herself had some Jewish friends—Jewish insofar as they were born Jewish, though they were otherwise indistinguishable from her other friends. Her grandparents still remembered what Poland was like when there were still many Jews around, but nowadays, it was only the Vietnamese. A museum couldn’t bring back the Jews, she said, but it could bring back the memory of a better Poland.

Suggested Reading

Lucky Grossman

Vasily Grossman was one of the principal voices of anti-Nazi resistance, and a legendary journalist who spent 1000 days at the front during World War II.

Cri de Coeur

The Short, Strange Life of Herschel Grynszpan: A Boy Avenger, a Nazi Diplomat, and a Murder in Paris.

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In