Between Literalism and Liberalism

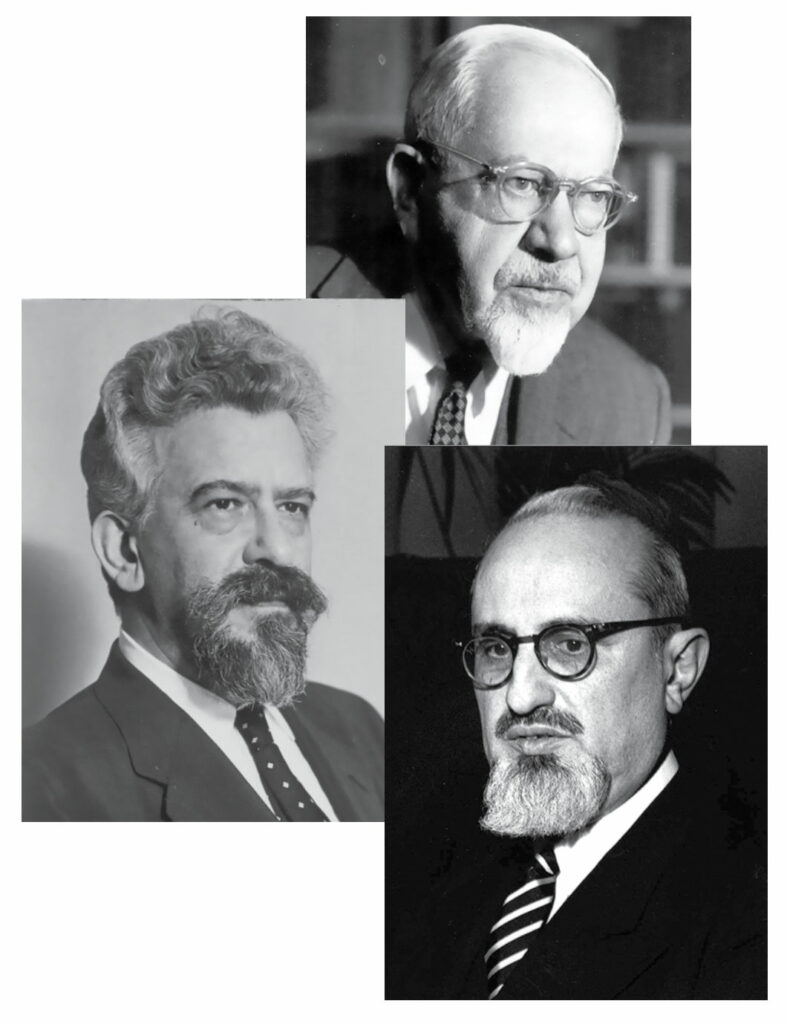

What first strikes the reader of Michael Marmur and David Ellenson’s excellent new anthology of 20th-century American Jewish thought is that its best-known and most influential voices are not really American. The great triumvirate of American Jewish theology—Abraham Joshua Heschel, Mordecai Kaplan, and Joseph B. Soloveitchik—who, along with Buber (and to a lesser extent Rosenzweig and perhaps Levinas), still dominate the field, were not born in America. As for American Jewish theology itself, one is tempted to repurpose Voltaire’s quip about the Holy Roman Empire—that it was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. That, perhaps, is one reason why Ellenson and Marmur chose the more capacious category of American Jewish thought, though one might argue that the choice sidesteps a problem rather than solving it.

The chapter headings under which Marmur and Ellenson place their selections are, in this regard, revealing. After the traditional theological categories of “God” and “Revelation and Commandment,” come “Spirituality,” “Hermeneutics and Politics,” “The Holocaust and Israel,” “Feminism, Gender, and Sexuality,” and “Peoplehood.” These latter categories suggest the extent to which American Jewish thought is dominated by concerns that are as much social and political as they are religious. In their introduction, Marmur and Ellenson quote the great sociologist of religion Peter Berger, who observed that modern religion “came to inform and direct fewer and fewer areas of life for most people, thereby leading to a compartmentalization of religion into distinct precincts and the diminution of its influence on the public square.” More than that, its authority over the private sphere has diminished as well. To adapt the 19th-century poet Judah Leib Gordon’s famous line, it turns out to be less compelling to be a Jew at home when one is just a citizen in the streets. This is not so much a problem for modern American Jewish thought as the context in which it must inevitably be pursued.

Jewish thought was once “easier” than it is now: Philo had to integrate only Plato, and Maimonides had to reconcile with only Aristotle. Moreover, Jewish thinkers were once more preoccupied with explaining what God commands than why. Although there was a vibrant premodern tradition of inquiring into the “reasons for the commandments” (ta’amei ha-mitzvot), if it could just be understood precisely what the mitzvot were, the job was mostly done. Medieval rationalists and mystics disagreed on the reasons for the commandments and even what it meant to say that in fulfilling them, one was satisfying God’s will or desire. That there were commandments and a legal system that spelled them out was not really in doubt. This was not just a matter of theory; it was a matter of social fact. Jews lived in communities in which observance of the mitzvot was a way of life. To return to Peter Berger’s terms, they lived under “the sacred canopy” of the Torah in both public and private life.

However, once the life of mitzvot is not a communal given and the notion of a divine being who cares about what one eats becomes difficult to believe, the burden on Jewish religious thinkers is not merely to find symbolic or pragmatic reasons for the commandments but to justify them as commandments at all. “Because He—or the authoritative tradition He authorized—said so” no longer serves, and the main problem is only secondarily the male pronoun. Most troubling is the idea of the commandment itself. Those who still believe in God think of the divine being as the creator of an impossibly vast and complex universe and wonder how that God of supernovas and quarks could be concerned with one’s dishes. Moreover, the very idea of being a metzuveh, one who is commanded, affronts the modern ideal of human autonomy.

Thus, most modern Jewish thinkers have turned from explanations of obedience to ideologies of encouragement: you should make this practice part of your life for the following reasons . . . But none of these reasons is as compelling as a divine command, and liberal theology, and to some extent even Orthodox theology, has been a series of attempts to craft a rationale that delivers some sense of obligation. Yet “you should” will never be as compelling as “you must.”

Orthodox and neotraditional thinkers such as Soloveitchik and Heschel tried to meet the challenge by evoking the depth and human wisdom embodied in the experience of living the commandments. These phenomenologists of Judaism took the data of tradition as given; they were tour guides, not counsels for the defense. Soloveitchik and Heschel both unpack the riches of the commandments within the context of the tradition they presuppose. “When Halakhic man approaches reality, he comes with his Torah, given to him from Sinai, in hand,” writes Soloveitchik at the outset of the selection from his most famous work, Halakhic Man. Anyone who approaches the world with awe and wonder (Heschel) or through study and struggle (Soloveitchik) must come to the same place as the author. As the great Jewish philosopher Emil Fackenheim once wrote about Heschel, “He has no feeling for the tragedy of unbelief.”

Michael Wyschogrod, who studied with Soloveitchik and was appreciative of Heschel, expressed perhaps the most emphatic if idiosyncratic affirmation of the tradition as it stands, arguing in his still undervalued classic The Body of Faith: God in the Jewish People that Jews really are the chosen people in the most literal sense. “God did not formulate a teaching around which he rallied humanity,” he wrote. “God declared a particular people the people of God.” He even interpreted the straying idealism of modern Jews as a misguided expression of that very chosenness:

If the Jewish attraction to Marxism was sin, it was the sin of the elect because it took the form of thirst for righteousness. And the same is true for Jewish secular liberalism. If secular Zionism was sin because it rejected God as the source of Jewish redemption, it was the sin of the elect because, however secular its rationale, it was a longing for the holy soil of Israel. Even in sin, Israel remains in the divine service because the spiritual circumcision that has been carried out on this people is indelible.

This is bracing, but it is not an argument designed to convince the secularist that she is, in fact, sinning in her rejection of the demands of the covenant.

One of the great virtues of Ellenson and Marmur’s anthology is it ranges far beyond such canonical thinkers (the drawback is that the selections are consequently very brief, sometimes little more than a page). Among the recent and less familiar thinkers are those who try to expand the range of voices in which the tradition speaks. Here one finds feminist and queer thinkers and, more generally, those who offer alternative metaphors for viewing God consonant with modernity’s expansive and increasingly nonhierarchical outlook. Such theological expansion argues that either we have never properly understood Judaism, because the tradition was too one-sided as a result of external sociological factors, or that the tradition was properly understood but must now be challenged and changed. Such challenges are important, but they, too, tend to sidestep the radical question of why the tradition shouldn’t just be jettisoned altogether.

Some of the most interesting selections come from scholars who illuminate this or that aspect of Judaism, whether it is José Faur on talmudic semiotics, Leo Strauss on the differences between Greek and Jewish thought, or Hannah Arendt on “the Jew as pariah.” Such essays sketch the fascinating intellectual history of American Jewry, but they make no comprehensive claims about the tradition, nor do they seek to motivate their readers as Jews. Even an excellent and unabashedly normative essay like Nancy Flam’s “Healing the Spirit” argues that Judaism provides healing resources but not that Lurianic Kabbalah is anything more than a “mythic structure that has caught the progressive Jewish imagination.”

Having read through these essays, a powerful question remains: Can this work? Will it sustain American Judaism? To understand the question more deeply, we must turn to Mordecai Kaplan. Although Kaplan, like his peers Soloveitchik and Heschel, was born in Eastern Europe, he came to the United States when he was eight years old and indeed contributes the most “American” theology of the original group of Heschel and Soloveitchik. Kaplan’s thought marks the shift to a distinctively American and unabashedly modern idiom. In fact, this is why Ellenson and Marmur begin their anthology in 1934, the year Kaplan published his classic work Judaism as a Civilization.

A thorough modernist who was deeply influenced by John Dewey and the pragmatist turn in American thought, Kaplan argued that there must be a Copernican shift in Jewish thought: not God but the Jewish people at the center of the tradition. Judaism, according to Kaplan, is not a divine system of law; it is a human civilization, marked by folkways. Kaplan’s God is not the commander at Sinai but a force moving through the people of Israel. Chosenness, too, must be discarded, for there is no chooser. “Why,” Kaplan asks, “continue practices that aimed at salvation in ancient times?”

The answer is that, as Jews, we feel impelled to maintain the continuity and growth of the Jewish people. There can be no ultimate good or salvation for us, either as individuals or as a group, unless we are permitted to express ourselves creatively as Jews. The conditions essential to our salvation must therefore include those that enable us to experience continuity with the Jewish past, as well as make possible a Jewish future.

If this sounds circular, that’s because it is: those of us who feel impelled to maintain the continuity and growth of the Jewish people must make ourselves continuous with its past. But, as Kaplan famously said elsewhere, “history has a vote not a veto,” which is, de facto, the model of all but the most scrupulously Orthodox. Where does that leave us?

One Friday afternoon, I was walking down a street in Beverly Hills and spotted a number of my congregants sitting at an outdoor restaurant. I stopped to chat and said, innocently, “I didn’t know Friday was Sinai Temple day here.” One of them said, completely unselfconsciously, “you should be here Saturday—it’s where we all come after shul.”

Many of my congregants are more traditional than those who attend other conservative synagogues, yet they gather at a restaurant on Saturday. Moreover, they have little consciousness that telling their rabbi this is anything out of the norm. Any rationale I could proffer, whether historical continuity, personal spirituality, or communal solidarity, could still be trimmed to fit having lunch at a treif restaurant on Shabbat afternoon. The only rationale that will not yield is: God said you must not do this. It did not occur to me to say it, and, had I done so, it would not have occurred to them to believe it.

If I launched that theological broadside, I would have heard objections not too dissimilar from those the Rabbis of the Talmud put in the mouth of Korach—does God truly care for the fine particulars of laws? If I put cheese on this burger or meet my family for lunch on Shabbat or drive to the beach to see the sunset, is the Creator of the Universe offended? Kaplan had an answer of sorts: we continue ritual practices because we are the people who do those practices. Then again, my congregants could easily have channeled Kaplan himself in their reply: “history has a vote not a veto,” so what’s so wrong with enjoying a sunny afternoon with good friends and good food? “Shabbat,” I sometimes hear, “is about resting, and I find this or that activity restful.” When the law’s particulars dissolve, the principles are invoked to justify behaviors the law could never countenance.

For a few generations, the momentum of history carried American Jews forward. The early Conservative Jewish movement in which Kaplan was ambivalently ensconced was about loosening the strictures that made American life difficult for people whose commitment to Judaism was intact. But the question for American Jewry now is not how does a committed person adjust to America, but how does a serious American but uncommitted Jew become motivated?

This anthology does not lack daring or seriousness or depth. Could there be a more shocking theological proposal than the following from Mara Benjamin?

The care for an infant perfectly captures the pairing of command and love at the heart of rabbinic thought. If God is not only loving parent but demanding baby, we may find within ourselves the resolve to meet the demand.

One’s obligation to an infant child is nonnegotiable, but that is because babies are helpless. We may doubt, however, that mitzvot would be more compelling if we think of God similarly.

The feminist theologian Judith Plaskow writes, “our legal disabilities are a symptom of a pattern . . . that lies deep in Jewish thinking.” She, Rachel Adler, and others offer deeply serious and learned rereadings of the tradition. Jane Rachel Litman summarizes the broader approach in the context of her essay on gender: “As Jews we claim the right to pursue our varied Jewish paths without coercion from the majority or claims of biological determinism; I suggest that as queer people and allies, we must do the same.”

And yet. The fast disappearing daily minyanim in non-Orthodox synagogues are primarily peopled by the more traditional congregants. The uniquely Jewish institutions of our lives—the day schools and camps and kosher restaurants—continue to diminish in non-Orthodox communities. Although there are, as evidenced in this anthology, serious and brilliant contemporary liberal Jewish thinkers, the number of serious liberal Jews is shrinking. While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

The creativity, range, and interest of the excerpts in this anthology are impressive. The introductions are crisp and clear. But the entire enterprise teeters—if it even is a single enterprise. Perhaps there is some promise in the fragmentation, however. “‘Like a hammer that breaks the rock in pieces’ (Jer. 23:29), so also may one biblical verse convey many teachings” (Sanhedrin 34a). When large systems of thought collapse, the ground is fertilized with their fragments. As the Kabbalah scholar Daniel Matt writes in another tantalizing selection, “Some of what we know from the Written Torah will need revision. Guidelines are not absolute. They change in the light of other wisdom, other renderings of the alef.” That first letter of revelation is silent, and in our cacophonous world, there are innumerable choruses to fill it in, each holding fast to a different letter or verse. Marmur and Ellenson’s excellent volume does not provide definitive answers for 21st-century American Judaism, but here are some of the voices we need to help fill those silences, some of the fragments out of which a new Judaism may be built.

Suggested Reading

Michael Wyschogrod and the Challenge of God’s Scandalous Love

The late Michael Wyschogrod may have been the boldest Jewish theologian of the 20th century.

Conservative Judaism: A Requiem

In 1971, 41 percent of American Jews were part of the Conservative movement. Today it's 18 percent and falling fast. What happened? Maybe its leaders never knew what Conservative Judaism was really about.

Three Portraits of Jewish Excellence—at 29

At the age of 29, David Ben-Gurion was speaking to empty halls across America for the Zionist movement and Leo Strauss was finding the “theological-political predicament” insoluble. As for Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, he was in Berlin worrying about epistemology and halakha. Three portraits of Jewish excellence in the making.

Who Is David?

Scholars and lay readers remain fascinated by the biblical stories of David and the history behind them, as a new batch of books shows.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In