Letters, Fall 2010

Defending Steinberg

One of the many extreme opinions Ben Birnbaum shared in “Posthumous Prophecy” (Summer 2010) is his belief that Steinberg was not a storyteller. This is startling. Steinberg’s first novel, As a Driven Leaf, is required reading on course lists for many day schools, confirmation classes, adult education programs, and rabbinical schools. Milton Steinberg’s consummate storytelling has enabled contemporary readers to link our religious dilemmas with those of our rabbinic sages. Those same storytelling talents and skills were the ones Steinberg, the preacher, used to deliver his sermons and build his pulpit.

There is a long tradition of bringing out the unfinished works of writers we greatly respect (Agnon’s Shira, Nabokov’s The Original of Laura, Heine’s Rabbi of Bacharach, and Kafka’s works, to name a few). Yet the publishing of an unfinished work is often a controversial act, and rightly so. It should never be taken lightly or with solely commercial interests in mind. We don’t know what The Prophet’s Wife would have looked like had Steinberg taken it through all the steps to completion. He was, as a writer, brilliantly able to infuse philosophical and theological ideas into his fiction. According to Steinberg’s son Jonathan (writing in the Jewish Quarterly Review), at the time he was writing The Prophet’s Wife, the author was in the process of formulating a modern systematic theology. We can only guess at what interplay of ideas and emotion Steinberg might have been trying to create with this not yet completed work.

All we have are uncertain clues. Even so, I have no doubt in my mind that publishing Steinberg’s novel-in-progress was the right thing to do.

Beth Lieberman

Project Editor, The Prophet’s Wife

Los Angeles, CA

Years ago, I implored my writing students: “Read what the writer does, not just what the writer doesn’t do.” Ben Birnbaum’s mean-spirited review of Milton Steinberg’s The Prophet’s Wife violates the principle to absurdity.

In his novel, Steinberg creates a new midrashic reading of Hosea, one of the harshest texts in the Bible. “Go and marry a harlot,” God says. Traditional reading sees Gomer as Israel, whoring after false gods, deserving hideous punishments. In Steinberg’s creation, Gomer is not a harlot. She is a loved wife, though forced into marriage, and seduced into adultery by Hosea’s brother. Steinberg permits her to live as a woman, and permits Hosea to be merciful to her. On the sword-edge of the Holocaust, Steinberg wished, I believe, to mitigate the hardness of God’s voice.

Steinberg had the idea that if he made Gomer a prisoner of her zeitgeist, and Hosea a merciful husband, he would have something important to add to the interpretation of the narrative, and to the theological dialectic of justice and mercy. From details furnished by Steinberg for the inner lives of his characters we see new dimensions to the story we had been too quick to understand too simply.

Gomer is granted more life by Steinberg than the Bible narrative that crushes her into symbol. A beginning has been made in breaking up the cement of received ideas about the inexorable need for punishment of the people of Israel, and about the use of a woman as exemplar of faithlessness and filth.

Birnbaum complains about what he perceives as Steinberg’s writerly shortcomings, but he never addresses the question of what Steinberg reached for in his novel, the theological daring of it, or why Steinberg struggled on his deathbed to complete it. He grants it nothing at all. Possibly he dislikes fiction, the necessary coarseness, compared with the clean abstractions of the essay. He insults the novel and its commentary, the Steinberg family, and the publisher by cynically seeing The Prophet’s Wife as a ploy to exploit the enduring success of As a Driven Leaf.

Birnbaum jeers down the rabbi novel-writer who tried to make us see what he imagined: Gomer-the blundering Jewish people-worthy of mercy and love. The forties was not a time to accept the notion that evil inflicted on Jews was the fault of their own sinning-nor, post-Holocaust, can it ever be again. To shift the balance in the dialectic of justice and mercy is, I believe, the triumph of Steinberg’s novel.

The Prophet’s Wife is radical new thinking poised against traditional reading. Milton Steinberg, the esteemed rabbi, polished writer of theological tomes, had the humility to step away from his exalted image and write a novel that would illuminate, as only fiction can, the daring ideas he passionately held. He had the brains and spirit and courage-the guts-to do it, and that is why, as a novelist, I honor the novelist in him.

Norma Rosen

New York, NY

Ben Birnbaum Responds:

Contrary to Ms. Lieberman’s contention, I do not object on principle to the publication of posthumous and unfinished works, but her comparison of Milton Steinberg with Agnon, Nabokov, Heine, and Kafka is hard to credit. As for Ms. Rosen, her efforts-here and in her “commentary”-to make of The Prophet’s Wife a display of “radical new thinking” that views women and the fate of Jews more cogently than do books rooted in the Bronze Age is, in a way, admirable. Unfortunately, whatever Steinberg’s intentions and Ms. Rosen’s hopes, the broken volume he produced (and, which Behrman House made little effort to buttress) just isn’t strong enough to carry the theological freight. I do agree that Steinberg grants Gomer more life (however thin) than does the Tanakh, but given that Gomer’s name is mentioned only once in Hosea, and her actions restricted to silently bearing illegitimate children offstage, it hardly seems an achievement worthy of real celebration.

Spy Stories

I would like to add two additional notes to Steven Zipperstein’s comprehensive account of Mark Zborowski in “Underground Man” (Summer 2010). Zborowski was one of the very few persons who knew where Leon Trotsky’s archive was located in Paris. It had been deposited there by the Institute of Social History in Amsterdam, which was the depository of almost all the radical papers in Europe. When Zborowski complained to his Russian handlers that the theft of Trotsky’s papers might reveal his role as the spy inside the Trotskyist movement, they replied, “Well, we wanted to give Stalin a birthday present.”

There is also a very good account of Zborowski written by Elisabeth Poretsky, the wife of Ignace Reiss, the murdered former director of the GRU in Western Europe, in her book Our Own People: A Memoir of ‘Ignace Reiss’ and his Friends, with a preface by Sir William Deakin, the first Warden of St. Antony’s College, Oxford.

Daniel Bell

Cambridge, MA

Rashi & Richard the Lionheart

In “Rashi and the Crusader: A Legend” (Summer 2010), Professor Matt Goldish reproduces a version of the Rashi-Godfrey legend from R. Gedaliah ibn Yahya’s The Chain of Tradition. For those who wish to find more about this fascinating story, please see our article “Rashi and The First Crusade: Commentary, Liturgy and Legend” (Judaism, Spring 1999).

The version you printed is an abridgement of the original with several inaccuracies, including the name “Gottfried in the Greek Tongue,” the Greek part being an inept “correction” of the text by a scribe ignorant of the city of Bouillon. Gedaliah’s full-length version offers rich historical detail. It appears a composite of a plausible connection with Rashi in Spring 1096 joined to the failed campaign of Richard the Lionheart nearly a hundred years later. (It contains a verbal map of Godfrey’s route to Palestine that is actually a very accurate depiction of Richard’s!) History tells us that Richard returned to Europe accompanied by only a few bodyguards after losing his army. A “great warrior” was thus humiliated, as Rashi predicts, but it was not Godfrey.

Gedaliah may have gotten the legend through his father, a disciple of Rabbi Yehuda Mintz (d. 1508), Chief Ashkenazi Rabbi of Padua, Italy, whose name indicates his family’s origin in the Rhineland. The composite legend itself probably dates to the 1190s.

Harvey Sicherman, Ph.D.

Gilad J. Gevaryahu

Lower Merion, PA

Matt Goldish Responds:

Many thanks to Dr. Sicherman and Mr. Gevaryahu for this important reference. The lack of much clear evidence about the events in this story renders any historical conclusions largely speculative. My friend Menachem Butler has also pointed out the detailed discussion of Lucia Raspe, “A Medieval Sage in Early Modern Folk Narrative: The Case of Rashi and Godfrey of Bouillon,” in Raschi und sein Erbe, edited by Daniel Krochmalnik, Hanna Liss, and Ronen Reichman.

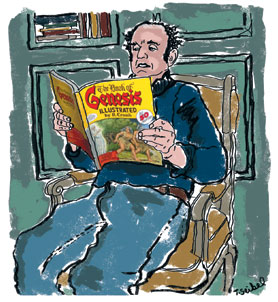

Harvey Pekar (1939-2010)

The Jewish Review of Books mourns the passing of Harvey Pekar whose comics-with Tara Seibel’s

gorgeous illustrations-graced our first two issues. We will miss him.

Suggested Reading

Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

Moses, Aaron, and Pharaoh Walk into a Bar: Passover in the Union Army

Yankee ingenuity at Passover: how one regiment made a Seder in the midst of the Civil War.

Fictional Revisionism

The first time I picked up Joshua Cohen’s new novel, The Netanyahus: An Account of a Minor and Ultimately Even Negligible Episode in the History of a Very Famous Family, I put it down when I reached page eighty-four.

Our Man in Beirut

The Arab Section, suggests Matti Friedman, in one of his latest book's nicer lines, “needed men idealistic enough to risk their lives for free, but deceitful enough to make good spies.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In