Victim Enough? The Jews of North Africa During the Holocaust

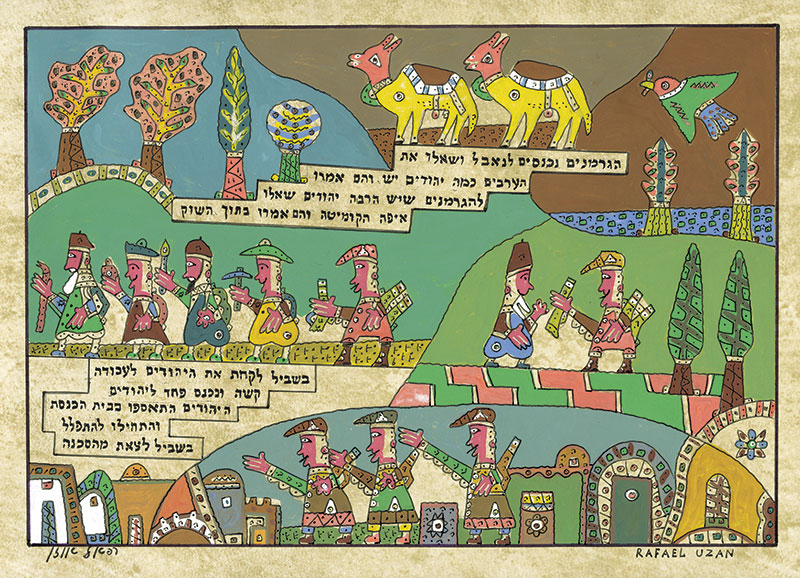

Soon after the fall of France in 1940, on the anniversary of his ascent to the throne, the sultan of Morocco, Muhammad V, held a banquet. Present at the palace were officials from the collaborationist Vichy regime who had forced him to sign laws setting educational and occupational quotas for the country’s Jews and requiring them to move back into their ghettos. Present too, however, was a group of rabbis the sultan had sneaked into the palace in a supply wagon and seated next to the French officials. Appalled, a Vichy representative wrote back to his superiors:

For the first time, the Sultan invited representatives of the Jewish community to the banquet and placed them most obviously in the best seats, right next to the French officials. The Sultan had wanted personally to introduce the Jewish individuals present. When the French officials expressed surprise at the presence of the Jews at the meeting, the Sultan told them: “I in no way approve of the new anti-Semitic laws and I refuse to be associated with any measure of which I disapprove. I wish to inform you that, as in the past, the Jews remain under my protection and I refuse to allow any distinction to be made among my subjects.”

On another occasion, the sultan told the Jewish community representatives that “I consider you to be Moroccans in the same capacity as Muslims, and your property, like theirs, will not be touched.” Later, he invited another group of Jews to his son’s circumcision, telling them that “my palace is open at all times.”

Were these the actions of a decent and courageous man, an assertion of sovereignty by a beleaguered sultan, or merely a negotiating tactic by a clever, if powerless, leader? And even if it is only a myth that the sultan threatened to wear a yellow badge himself if the Vichy regime forced them upon the Jews, what is the backdrop to Muslim-Jewish relations in North Africa during World War II that distinguishes it from the European experience?

Indeed, in the absence of death camps, crematoria, and skeletal survivors, is it fair to speak of the experience of Maghrebi Jews and that of their European coreligionists during the Holocaust in the same breath? Aomar Boum and Sarah Abrevaya Stein, the editors of the fine new collection The Holocaust and North Africa, think so, albeit with historical nuance. “[T]he Holocaust was experienced by Jews in North Africa,” they write, “through the implementation of French and Italian racial laws, the expropriation of property and economic disenfranchisement, and internment and forced labor.”

In the years leading up to the war, roughly 470,000 Jews lived in the countries of North Africa: 240,000 in Morocco, 110,000 in Algeria, 80,000 in Tunisia, and 40,000 in Libya. Some of these Jews traced their ancestry to traders who accompanied Phoenicians in the 9th century B.C.E., others to those who fled Roman Palestine after the destruction of the Second Temple, still others to those expelled from Spain in 1492. Notwithstanding moments of pillage and chaos, when regimes teetered and tyrants reigned, there was, unlike most periods in Europe, no endemic history of anti-Jewish depredation in North Africa. So long as they remained apolitical and deferential, Jews were often ignored but rarely mistreated. One way of accounting for the position of Jews in North Africa as opposed to those living in Europe is to think of them as intimate and valued strangers who occupied an interstitial place in the organization of Muslim society.

If you have even the most passing notion of the Arab world, it probably includes an image of the bazaar, a marketplace in which hawking and haggling are rampant and the prices depend more on patron-client relationships than impersonal market mechanisms. If you then think of this social world as rather like the bazaar, you can picture a culture in which people are constantly building networks of indebtedness that define who they are. It is a world in which a loan can be repaid with a marital intervention or a political favor, virtually all relationships being negotiable, a matter of what the traffic will bear. In this complex pool of exchange and favor, obligation and ingratiation, the Jew is betwixt and between—too weak to be a potent ally, too distant to be a member of the family, but by that very weakness immunized from certain entanglements.

Not being fully part of the dominant society’s scheme of reciprocity had its advantages: A Jew could, for example, enter a Muslim’s home to repair the plumbing but was not likely to use his knowledge of the house or its inhabitants to help a Muslim acquaintance gain a bargaining advantage; he could keep a Muslim’s confidence but wasn’t likely to convert it into a marital alliance. Since, as the Arabic saying goes, “your neighbor who is close is more important than your kinsman who is far away,” the nearby Jew could be viewed as neither intrusive nor threatening. Like that stranger you meet while traveling and to whom you might tell things you wouldn’t tell a friend, the Jew occupied a crucial space in traditional Muslim society, all of whose other relationships implied claims of obligation. Like women (to whom they were commonly compared) a Jew was both weak and valuable. To this day in North Africa, a house abandoned by departing Jews may be left alone by Muslim neighbors in the belief—at least among an older generation—that in their return a missing part of local self-regard will be restored.

It was into this complex traditional culture that the European colonist—and at the time of World War II the European fascist—intruded. The repercussions, however, were not identical throughout North Africa. Algeria, which had been conquered (though not fully pacified) in 1830, was rendered an integral part of France. As a result, it saw the settlement of tens of thousands of Europeans in both urban and rural areas, many of whom came to regard themselves as a distinct racial population. When Jews were made French citizens by the Crémieux Decree in 1870, Muslims raised few objections, but as nationalistic sentiment clashed with settler interests the sense of Algeria as comprised of separate racial groups increased significantly. Morocco, which became a French protectorate in 1912, contained by far the largest number of Jews in the region in part because, as both traders and noncompetitive neighbors, they played a key role in Moroccan society. In Tunisia, which fell under colonial sway in 1881, the Jews quickly adopted much of French culture and identified heavily with the “civilizing mission” of the colonial power. Libya, which became the Italian prize in the scramble for African colonies, is remembered by Jews who lived there in the prewar years as a place of close familial and community ties, warm relations with immediate Muslim neighbors, and increasing tensions as Mussolini’s policies took hold.

Following the fall of France and the establishment of Vichy’s control over the country’s overseas territories, the Crémieux Decree was revoked, thus depriving those Algerian Jews covered by it of their French citizenship. After the Allied invasion of North Africa in 1942, many of the Nazi racial laws were lifted, but the Crémieux Decree itself was not restored. As Hannah Arendt argued, in a paper written for the American Jewish Committee, the failure to reestablish such citizenship was not for the stated reason that it would create an inequality between the Muslims and Jews of Algeria (thus further inflaming nationalist sentiment) but because colonialism worked, in part, through the bureaucratization of racial divisions. Indeed, she argued, the Nazi program was modeled on the imperialism and colonialism practiced outside of Europe and the linkage of racism, bureaucracy, and mass murder that characterized events in a number of the colonies. If we combine Arendt’s insight with an understanding of traditional Muslim social life as built on webs of indebtedness, it becomes possible to begin to understand the wartime experience of Jews in North Africa.

In Algeria, for example, the hostility of the resident colons (later called pieds noirs) to the Jews was palpable. Theirs was indeed the anti-Semitism of European heritage, but even so it took on local coloration as a vehicle for asserting that the Muslims too were a distinct and inferior race. Local officials, working with Vichy, set up about three dozen camps in Algeria (along with two dozen in Morocco and a handful in Tunisia and Libya) where some resident Jews, political prisoners from Europe, and Algerian Jewish soldiers serving in the French army were incarcerated. Treatment in those camps located at the edge of the Sahara was harsh, but actual murder was rare. Several of the contributors to the present volume note that in a number of instances Muslim guards refused orders to harm the Jewish prisoners. Similarly, with regard to Tunisia, the only North African country directly occupied by Germany for a few months, Daniel Lee shows that, while the later claim by Vichy officers that they did not really enforce the racial laws is untenable, it is clear that their overriding concern was how to maintain their own colonial control. Some prisoners from both countries were sent to concentration camps—but not death camps—in Europe; most of them survived.

Libya forms a distinctive case. As Jens Hoppe points out, in 1931 there were 25,000 Jews in Libya and only 39,000 in all of Italy. Local Italian fascists attacked Jews in Tripoli and Benghazi on several occasions in the early and mid-1930s, but, as Aomar Boum and Mohammed Hatimi argue, for the southern part of Morocco, German anti-Semitic propaganda had no real effect on the local Muslims. Indeed, many Muslims took Jews into their homes to protect them from the colonial administration during this period. Ironically, it was only after the British recaptured Libya in 1942–1943 that some Muslims attacked the Jews (who, while the British turned their backs, bravely defended themselves), believing them to support continued Italian control over national independence.

The contributors to this collective volume are faced, like so many of the Jews who lived through these years, with the question as to how the North African experience should be treated within the broader context of the Holocaust. While the Jews of North Africa did suffer they were not subjected to a program of systematic genocide. On the other hand, the Jews of the region—and more particularly much of the Israeli establishment—have either remained silent about their experience or downplayed it. If, as the editors state, it is necessary on behalf of North African Jewry to “push the boundaries of Holocaust history [because] justice has not been served,” this still leaves open the question of how and to what end their history should be included in the larger narrative of the Holocaust. As the Tunisian Jewish novelist Albert Memmi wrote, “I am not enough of a victim; that is why my conscience is tortured.” Must the Jews of North Africa, as contributor Lia Brozgal puts it, write “a history that competes with a more catastrophic one, or be written out of history?”

Many of the contributors accept that the experience of the Maghrebi Jews was marginal to the events of the European Holocaust. But they also make the case that a view from the margins can be revealing. That the Nazis and Vichy cared so much to enforce their race laws, even (as Ruth Ginio shows) in French West Africa, demonstrates how deep-seated the connection between racism and the colonial venture was. As Susan Slyomovics shows in an excellent chapter, we can see how local populations succumbed to or resisted the colonizers’ racial categories as they responded to the plight of their Jewish neighbors.

Telling the story of the Jews of North Africa during the Holocaust also has practical implications. There is the question of the willingness of several European governments to include these Jews in their reparation programs. Perhaps more importantly, inclusion in the overall narrative of the Holocaust has a bearing on the place of Mizrahi Jews in Israeli society. By including their experience in this period one can better understand that while the North African Jews rarely lost their lives the Holocaust did cost them a cherished way of life.

In recent years several Muslim scholars have made their careers writing about the Jews of North Africa. Aomar Boum, who along with his coeditor Sarah Abrevaya Stein teaches at UCLA, returned to his home village in the High Atlas Mountains of Morocco to eavesdrop on the remarks Muslims made about the now-absent Jews and discovered a deep sense of loss by the older people who remembered their Jewish neighbors. However, this was not passed on to the younger generation, who think of Jews in stereotypical terms, predominantly as the oppressors of Palestinians.

Sultan Muhammad V—despite the urging of Shimon Peres and many others—has not been included among the righteous Gentiles honored at Yad Vashem. As the contributors to this volume demonstrate, it is important to understand how ordinary Muslims comprehended what was happening to their Jewish neighbors, to their country, and to themselves under Nazi and Vichy oversight. Even more importantly, we must understand the experience of the North African Jews themselves. Boum and Stein’s book is a good start.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

On Re-Reading a Banned Book: Nathan Kamenetsky’s Making of a Godol

Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky spent years on an odd, brilliant biography of his father. The book was banned, and one leading haredi rosh yeshiva said he had forfeited his share in the world to come. Now it is an underground classic that costs $2,503 on Amazon.

Heschel Transcendent

Abraham Joshua Heschel’s intellectual peers included Rabbi Joseph Soloveitchik, Reinhold Niebuhr, and the Lubavitcher Rebbe. His main thought, Shai Held argues, was of transcendence.

Awe and Joy

S. Y. Agnon curated a stunning anthology of Jewish texts, published later in English as Days of Awe. In his introduction to the anthology, the eminent scholar Judah Goldin grappled with the idea of awe—and so does this author.

The Wizard of Words and the Baggy Monster: Rereading Amos Oz’s A Tale of Love and Darkness

Israelis made Amos Oz a cultural symbol—almost a fetish—of who they thought they were or fancied themselves to be. But their adoration wasn't unconditional. Oz's editor, literary scholar Yigal Schwartz, called Israel’s unbalanced relationship with Oz a “bipolar reading disorder."

Gideon539

That's all very interesting... but it wasnt very long after this that most of the Jews of N. Africa were almost completely ethnically cleansed. Perhaps another useful insight to the way Jews formerly fit into the seems of Muslim society, as this article portrays... is the 'Dhimmi Contract'. Once broken, and 'infidels' had the nerve to expect things like self determination in the form of the reborn State of Israel... the Muslims turned on their local Jews en masse. Thereby reminding us that Anti-Zionism has always been a form of anti-Jew bigotry as well.

gershon Hepner

Abd Al Malik, born Régis Fayette-Mikano, the French son of Congolese immigrants, learned in eastern Morocco this proverb: “In a garden the flowers are diverse, but the water is one.” It is one I recall when, while reciting the haggadah at the seder, I reach the passage about the four sons, and point out that keneged arba banim does not mean "opposed to four sons." but implies full acceptance of their diversity, Reading Lawrence Rosen's wonderful review article made me wonder whether Sultan Muhammad V, a monarch who welcomed the diversity of his subjects, and insisted on protecting his Jews from the hostility of members of the Vichy government, may have been influenced by the eastern Moroccan proverb that so impressed Abd Al Malik. Whether or not this was the case, he and Abd Al Malik would surely have enjoyed my poem:

GARDEN OF DIVERSITY

In a garden, flowers are diverse,

but all require the same water.

Art is long and life is shorter,

but the feelings that all people nurse

towards them both may very greatly vary,

like the flowers in the garden:

Both can soften and can harden,

favorably sometimes, sometimes contrary.

Avram Stein

"...as the Arabic saying goes, “your neighbor who is close is more important than your kinsman who is far away,” Oh really? The source of the saying is the Bible. See Proverbs 27:10.

Gary Farber

"Oh really?"

I don't understand what perceived contradiction exists here. I'm pretty sure it's possible to be Arab and quote the Bible. I'm reasonably sure all the Christian Arabs would agree and I would hardly be surprised to find a Muslim Arab uttering statements made in either the Torah or the Christian bible. That would be utterly commonplace.

So an Arab quotes the Bible: so what? Is the Bible not a source of quotations? I don't get it. Muslims consider Moses, David and Jesus to be prophets.

It's also observable through the internet that hardly anyone cares about the actual source of a quotation. Most "quotations" are misattributed. It's not as if this is something newly invented by the internet. Again, so what?