Mashed Potatoes and Meatloaf

Joanna Hershon’s fourth novel, A Dual Inheritance, seems at first to contain few surprises. The novel begins when Hugh Shipley, a WASP, and Ed Cantowitz, a Jew, meet during their senior year at Harvard. They are different in all the predictable ways: Hugh is tall and aristocratic; Ed is short, dark, and hairy. Hugh’s childhood included country clubs, private schools, servants, a distant father; Ed’s childhood included city public schools and a yelling father.

The broad outlines of their personalities, too, seem to fall into familiar, almost stereotypical patterns of opposition: Hugh’s near apathy and Ed’s scholarship-kid hustle; Hugh’s noblesse oblige and Ed’s materialistic aspirations; Hugh’s ascetic remove from the girls who throw themselves at him and Ed’s way with women. Nor do the broad outlines of their adult lives carry major surprises. One does good in the Third World; the other goes to Wall Street (no points for correct guesses). Both are very prominent and successful, in the way that Harvard men, in novels, almost always are. That the two men fall out over the affections of Hugh’s one true love, the portentously named Helen, is also not unexpected.

And yet, from these overly familiar ingredients, Hershon concocts something satisfying and unexpected. She’s like someone who invites you over for meatloaf and mashed potatoes. You may not be very excited about that meal, but once you begin eating you realize that the food is superb and that you’ve been missing meatloaf.

Hershon’s secret is that she understands her ingredients very, very well. For instance, you are not surprised to find that Hugh is a sailor, but would you have pegged him as a weeper? And yet, following a heartbreak, Hugh “began what became (at least to his father) a comical extended crying jag, which would last on and off well into the fall.” Weeping is his human, unromantic, and un-romanticized response. There are two surprises here. The first, of course, is Hugh’s waterworks. The second is that, after a moment, this new detail seems not surprising, but necessary, obvious, and wholly right. It is so with almost all the unexpected moments in the novel.

Midway through the novel, when the two friends are already middle-aged, Hershon achieves a similar effect as she describes Ed’s stroll through New York City:

It was getting dark earlier now, and the air was crisp; everything was beautiful in that sad kind of way that he absolutely fucking hated.

The sentence begins with a common observation about fall, beauty, and sadness, but it’s Ed who’s thinking this, and the last three words in the sentence are both unexpected and a perfect fit for his character. Of course, I thought as I read, of course, Ed would just hate having melancholy autumnal thoughts. This kind of response can only be evoked by a writer who takes care in establishing characters.

The anti-mythologizing, anti-dramatizing tendencies of this novel are another pleasant surprise. Take Helen, whom we encounter through the hazy, idealizing gaze of the man who loves her and then through the eyes of others who bear her no particular fondness. To Hugh, Helen may seem like, “Grace Kelly’s more distinctive sister,” but to an older friend of his family, she’s “always seemed a touch off, no?”

In Hugh and Helen’s eventual adult relationship, and in others, this book may be suggesting that the idea of one true love is a fallacy, as much as the characters (and some readers) would like to believe otherwise. Ed, for example, encounters and re-encounters a good-looking, smart, practical, loyal, and Jewish woman named Connie. She pops up at least once a decade, and finally he, like the reader, begins to wonder whether they’re meant to be:

He remembered Connie’s warmth, her humor . . .

He remembered the sense that, while he was in her company, she was always looking out for him, and he remembered thinking that she, Connie Graff, was the woman he was supposed to end up with. And it was exactly this sense that he had turned from. He remembered when he’d turned from it—from her; it had felt, with its requisite bit of pain, exactly like freedom.

The beginning of this passage suggests that we are building toward a big romantic finish, as Ed recalls Connie’s sterling qualities and his sense that Connie “was the woman he was supposed to end up with.” But, in life, people are usually not so rationally romantic. After considering the possibility of this fate-favored love, Ed, rather casually, decides against it. In moments like this one, it is almost as if Hershon carefully builds a reader’s expectations, only to undercut them in a way that, too, seems perfectly logical and necessary.

In the novel’s masterful concluding sequence, Hugh and Ed, long estranged, are reunited at a daughter’s wedding. Helen and other important characters are there, too.

Such a set-up inevitably creates expectations for a wordy, lengthy, dramatic scene of conflict and reconciliation; that scene never comes, even though several of the characters try to precipitate it. Hugh (again, surprisingly) wonders whether he might have done more good for the world if he had left off humanitarianism and tried to make some “real dough,” a line of speculation that leaves Ed feeling not vindicated (as he perhaps would be in a less subtle book) but merely uncomfortable. Ed tells him he doesn’t really mean that, and Hugh responds with anger:

“You don’t think I mean what I say? Why? Because you know me so well? . . . Because we both know you don’t know me at all.”

“True,” Ed said. He let himself look at Hugh directly. “Or,” he let his eyes apologize, “I might.”

As soon as Ed expresses them, we realize that his doubts about Hugh’s potential as a financier are wholly correct: So, again, we have a reversal, and a reversal of that reversal, and land in a place that feels right. But all that is not nearly as important, to Ed or to the reader, as Ed’s struggle to reconnect. In this beautiful passage, we see how people—even stubborn, angry, self-righteous people—work to mend broken bonds and how, sometimes, they might even succeed.

When covering as much physical and temporal distance as Hershon does here, authors often end up creating characters as simple and distinct as paints on a color wheel. Such characters are easy to remember, and they certainly don’t distract the reader from a novel’s ideas. I am glad Hershon didn’t take this route and that her people are as complex, surprising, and rewarding as they are. Hershon hints at her aims for the novel in the passage below, also from the conclusion, and from Ed’s perspective:

Helen hadn’t mentioned his questionable business practices or the Times article or prison, and he wondered if and when she would. It then occurred to him that she might see him as nothing more than some kind of colorful character, a notion that made him queasy.

Ed’s queasiness with simplification (arising, perhaps, out of a fear of being ethnically pigeonholed as a Jew) is shared by the author. Hershon almost always makes choices that prioritize accuracy and faithfulness to the characters’ individual personalities.

What, then, are we to make of the novelist’s very occasional, seemingly half-hearted gestures toward some larger theoretical framework? The title and epigraph refer to dual inheritance theory, which, roughly, is the idea that cultural as well as genetic developments influence our actions. It is mostly left to the reader to draw the lines between such theories of “gene-culture coevolution” and the events in the novel. I was able to do that a few times: Although scenes are generally finely drawn, there are some set pieces depicting Ed’s father’s racism and Hugh’s father’s anti-Semitism, which seem to strain toward a larger point, just as ideas of communal and tribal qualities seem to appear every hundred pages or so, and then vanish without much effect. Perhaps Hershon is herself influenced by a literary culture that sometimes deems realistic stories by women, about relationships, insufficiently substantial. If she does not cede quite enough authorial control to allow her ideas about dual inheritance to emerge through her characters, she is, thankfully, also uncomfortable making more than a half-hearted attempt to submerge her characters in abstract ideas.

Ultimately, in the strongest parts of this novel, the ideas are the emotions, depicted carefully, moment by moment, and decade by decade. In a novel that pays such deep attention, emotions—and the characters they delineate—are enough. Like Allegra Goodman, Joanna Hershon seems more influenced by Victorian authors—perhaps George Eliot or Anthony Trollope—than by the new literary maximalism or other recent trends. In any case, as cooks and authors know, theory is no match for the unexpected. A few pages before the end, Ed’s daughter makes a decision about a love affair:

His daughter took a shuddering breath. “We’ll see,” said Rebecca, and now he couldn’t tell if she was shaking because of the change in the weather, or if, in fact, she might just cry. “I mean—we’ll see,” she repeated. “Who knows?”

He gave her a good strong hug. “Nobody.”

Suggested Reading

Jacob Glatstein’s Prophecy

Literary masterpieces that double as works of prophecy have been rare since the death of Isaiah. But the Yiddish poet Jacob Glatstein wrote two novellas that foreshadowed the future of Jewish Europe.

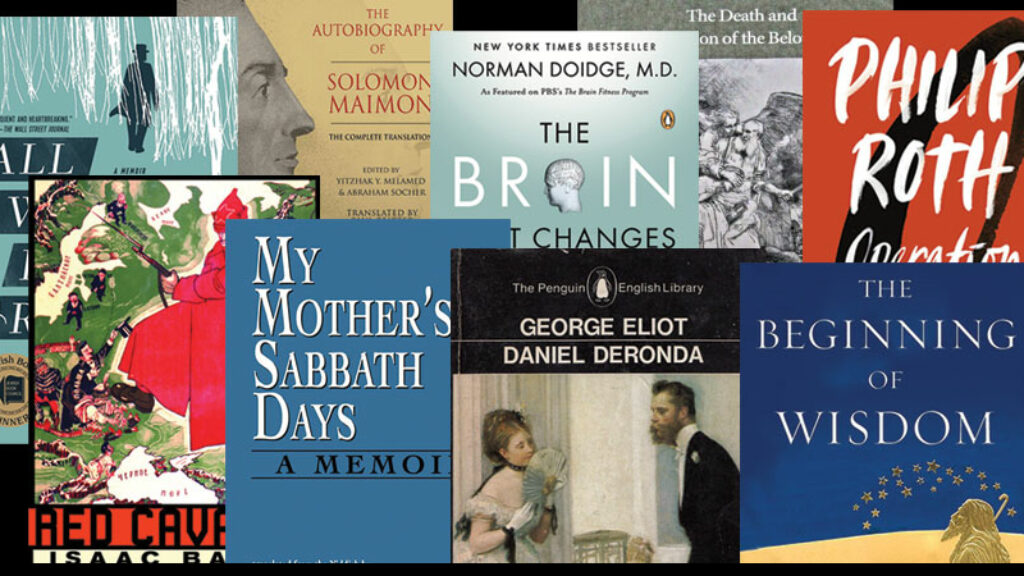

A Decade of Recommendations

In celebration of our 10th anniversary, we asked 10 of our favorite readers which books they had found themselves recommending the most over the last decade.

Videos from Our 2nd Annual Conference

Subscribers and registered users can now watch four sessions from our 2nd Annual Conference, held November 2016 in New York City.

An Indian Play in Warsaw

Janusz Korczak couldn’t save any of his beloved orphans from the Nazis. Jai Chakrabarti imagines one, and sends him to India. It’s a great premise, but does it work as a novel?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In