Is Beauty Power?

Helena Rubinstein had such a flair for self-invention—was she born in 1870, 1872, or 1880?—that even the venerable Harvard University Press’ reference work, Notable American Women: The Modern Period, informs the reader that Rubinstein attended the University of Kracow and studied medicine in Switzerland. In reality, she never finished secondary school, and hers was much more of a rags-to-riches story than she liked to admit. Her professed scientific expertise was part of the show, an expression of sheer entrepreneurial chutzpah and unrivalled self-marketing. Indeed, Rubinstein—known to all as Madame—was the P.T. Barnum of beauty.

By the time of her death in 1965, she had come a very long way from the genteel poverty of her distinctly unchic childhood home in Kracow’s Jewish district of Kazimierz, where she had been born Chaja Rubinstein. In her deft, highly entertaining biography, Helena Rubinstein: The Woman Who Invented Beauty, Michèle Fitoussi estimates Madame’s personal fortune at the time of her death at about $100 million. As for her business empire, “The Helena Rubinstein brand was established in more than thirty countries, owned fourteen factories and had a staff of 32,000 in salons, factories, and laboratories in fifteen different countries.”

And today? Her once independent company, now owned by L’Oréal, no longer maintains a single store in the United States, and Rubinstein’s name and once ubiquitous brand have receded from the spotlight. Yet Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power, the absorbing and handsomely mounted exhibition on display at New York’s Jewish Museum, makes a strong argument for her importance, and not only as an early Jewish female entrepreneur. Rubinstein was also a prodigious art collector who once bought out an entire gallery show of the work of Elie Nadelman, many of whose distinctive art deco sculptures are displayed here. She was also an influential decorator whose eclectic taste, showcased in her beauty salons and homes, broadened traditional notions of art while also promoting a modernist sensibility.

In keeping with Rubinstein’s taste for a decorative mélange, the galleries at The Jewish Museum juxtapose modernist, surrealist, and cubist paintings by Picasso, Braque, Léger, and Miro among others with arresting masks, statue heads, reliquary figures, and marionette headdresses from across African, Oceanic, and Latin American cultures—all of them pieces that were once part of her collection. The exhibit demonstrates how, through her own mix of personal and business alchemy, Rubinstein managed to effect a larger cultural impact than is generally acknowledged. “Through carefully considered publicity, she made her personal aesthetic taste an integral feature of her business,” exhibition curator Mason Klein writes in the accompanying catalogue. “Conversely,” he writes, “she used the private domestic space of her several homes to dramatically define and champion a multicultural identity and a nonhierarchical assessment of beauty.”

I’ll return to what this suggests about Rubinstein’s own identity as an assimilated Jewish woman. But I think that the most striking impression that those who view the exhibition (which will travel to Florida after its run in New York) or read Fitoussi’s biography will come away with is the inextricable mix of charm, targeted business savvy, and steely determination that made Rubinstein so forceful and flamboyant a personality. How else could Rubinstein have transformed herself from Chaja to Helena to “Madame”?

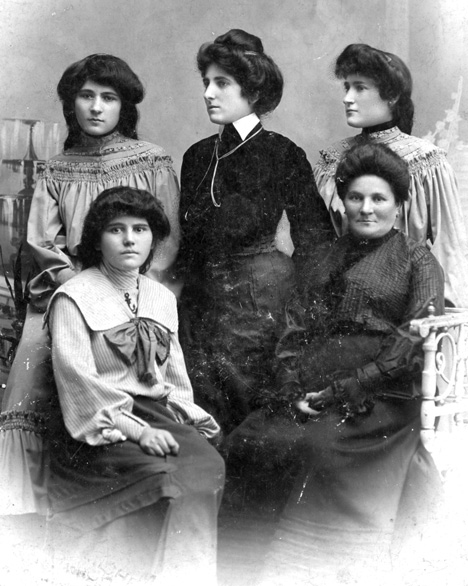

Given Rubinstein’s opulent later life and her predilection for massaging the details of her earlier one—her Torah-studying unsuccessful businessman of a father would become, in her telling, the owner of a vast estate—it’s illuminating to see the exhibition’s single trace of Rubinstein’s modest Kazimierz origins, a family photo from about 1888. In it she takes the central, dominant position amid three of her sisters and their mother. As the oldest of eight sisters in a traditional Orthodox family, Rubinstein had been expected to be the first to marry. Rubinstein, however, refused to submit to an arranged marriage. At odds with her father, she moved first to one aunt’s home in Krakow, then another’s in Vienna (where she improved her German while working for that family’s luxury fur business), and finally to an uncle in Australia. Although Rubinstein claimed to have always dreamed of the adventure of going to the outback, Fitoussi sets the record straight: “Everyone viewed the Australian solution as an honorable way out for an unmarriageable young rebel.” On her passport, she gave her first name as Helena.

At first, it was not a very promising rebirth. In 1896 at age 24 (both Fitoussi and Klein accept 1872 as her birthdate), Rubinstein arrived in the isolated, sheep-farming town of Coleraine, Australia. Her new life consisted of little more than tedious non-stop work as housekeeper and store clerk for her uncle. But during her time in Vienna, she had honed her gift for sales. And among her belongings were 12 jars of facial cream that her mother had given her. When the sun-baked local women would come into her uncle’s store, they would often comment on Rubinstein’s pale, unwrinkled face. How, they wondered, did she manage to maintain such a smooth complexion? In that question, Rubinstein spotted the market opportunity that would change her life. It was her special facial cream, Rubinstein would respond, would you like to try it? Of course they would. Soon she had far more requests from customers eager to buy the cream than her mother could possibly supply from Poland (it was made by family friend Jacob Lykusky and his brother). The only solution, Rubinstein realized, would be to figure out how to manufacture the cream herself. It took her several years and several moves, from Coleraine to Brisbane to Melbourne, to gather the financial and pharmaceutical backing to do so. Fortuitously, Australian sheep wool provided an inexpensive local source for the essential ingredient of lanolin. She opened her first beauty salon in Melbourne and offered for sale the Valaze (supposedly Hungarian for “gift from heaven”) beauty cream that would begin to make her fortune. It was also in Australia that she met her future husband, Edward Titus, another Polish Jew with a talent for reinvention. It wasn’t long before they left Australia behind for London, Paris, and ultimately New York.

By the 1930s, Helena Rubinstein’s salons were offering a glamorous array of “skin analysis, full body and facial massage, makeup, deportment and exercise classes, hairdressing, and lectures,” Klein writes. She had also formulated a full “Day of Beauty” that she marketed to clients with great success. As for applying those beauty lessons once they returned home, the list of products for sale ran to “629 creams, lotions, powders, rouges, lipsticks, nail and eye treatments, perfumes, colognes, soaps, and masks.” Rubinstein even made an early, though ultimately unsuccessful, attempt to find a market for men’s beauty products.

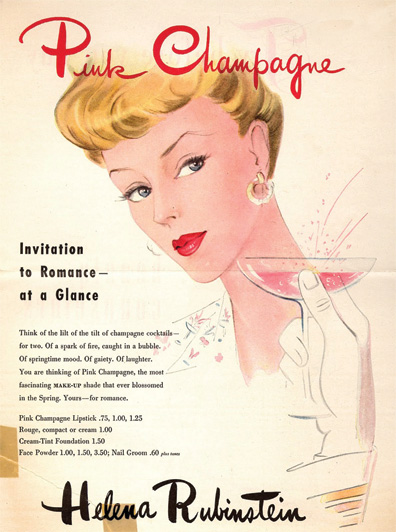

The Jewish Museum exhibit does a particularly good job of using advertisements and news and magazine accounts from the first decades of the 20th century to show how Rubinstein the woman became synonymous with Rubinstein the brand and how together they became ubiquitous. This early example of what is now called “branding” was largely due to Titus, who had a knack for advertising and publicity campaigns that captured the spirit of the moment. “Beauty Is Power” was one of his early slogans, a clever appeal to women eager for independent lives at the start of the suffrage movement. In another astute move, Rubinstein’s face—which, thanks to carefully retouched photographs, never seemed to age—often accompanied print advertisements as a personal promise of quality. Titus is also the one who cannily dubbed her “Madame,” an alluring aristocratic title for an exotic guru of beauty who spoke English in an accent no one could quite place. At the same time, his connections with various social and artistic circles in London and Paris increased the visibility of her brand among the elite style-setters of the time. It was Titus, you might say, who helped put Rubinstein’s name, as well as her make-up, on everyone’s lips.

Rubinstein’s great success funded not only a lavish lifestyle but a lifetime habit of accumulation. In addition to her extensive Western and non-Western art collections and the various homes and beauty salons she was constantly redecorating, Klein writes, “She had an irrepressible impulse to assemble a potpourri of objects—mounds of pearls and emeralds, costume jewelry, luxurious fabrics, Venetian Rococo mirrors” and more. Several display cases at the exhibit are devoted to the eye-catching, dramatically oversized, vividly colorful cuff bracelets, rings, and heavy necklaces she favored. One part of the exhibit is given over to the charming miniature rooms Rubinstein had displayed at her Fifth Avenue salon. Each reproduces in tiny, meticulous detail such diverse decors as a 19th-century London curiosity shop that Dickens would be proud of and an early 20th-century Montmartre artist’s studio reminiscent of a scene from La Bohème (they are on loan from the Tel Aviv Museum of Art). Today Rubinstein would be called a shopaholic, but if you acquire enough art you become a patron.

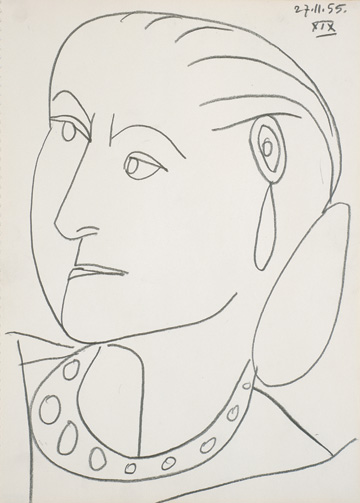

Her status as such is nowhere more apparent than in the gallery wall given over to an array of some of the many portraits she commissioned of herself through the decades. Most are idealized evocations of an ever-youthful Rubinstein often made to seem, even in her 60s and beyond, an alluring temptress. By contrast, in 1957 English painter Graham Sutherland dared to depict her in harsh brushstrokes as an aged autocrat, hawk-eyed, regal, and wary in a dazzling red and gold Balenciaga gown, her bejeweled hands folded in front, her hair pulled back in her characteristic severe chignon. Most revealing of all are the series of 12 sketches by Picasso in 1955, which capture an extraordinary range of moods, from the imperial to the sedate, from death-haunted fear to cold-blooded rage. Retouched photos and fawning portrait artists could lie, but Picasso’s eye did not.

So, beyond the brand, who was Rubinstein? Her marriage to Titus formally ended in 1938 (they had two sons, in whom neither parent, sadly, seemed to take much interest), and with her re-marriage to Prince Artchil Gourielli-Tchkonia, who claimed Georgian nobility and was more than 20 years her junior, Rubinstein re-invented herself, yet again, now as a titled princess, a fairy tale come true, more or less (Gourielli-Tchkonia’s claim on the title was a bit tenuous). Princess or not, Rubinstein continued to demonstrate products and expound on beauty for countless press interviews all over the world. “There are no ugly women, only lazy ones,” was one of her favorite sayings. Never lazy herself, she never stopped selling. Or bossing: A photograph shows her, in her last years, holding court while sitting up in her stylish Lucite bed, her executive staff sitting at attention all around her, awaiting orders in their daily morning meeting with Madame.

What’s clear throughout the exhibit is that the more successful Rubinstein became, the more her public and private personae melded together. It is almost impossible now to distinguish between Helena Rubinstein the woman and Helena Rubinstein the brand, what was for show and what was authentic. But what a showwoman she was: Although she was known for her extensive wardrobe of to-die-for haute couture designs by Balenciaga, Chanel, and Schiaparelli, among others (several are on display), in the exhibit she is also seen in a 1964 photo spread from Life, in one of her manufacturing plants, wearing the simple white lab coat required of her salon employees, as she vigorously stirs a giant vat of cosmetic cream. At four feet 10 inches tall, Rubinstein stands not that much higher than the vat.

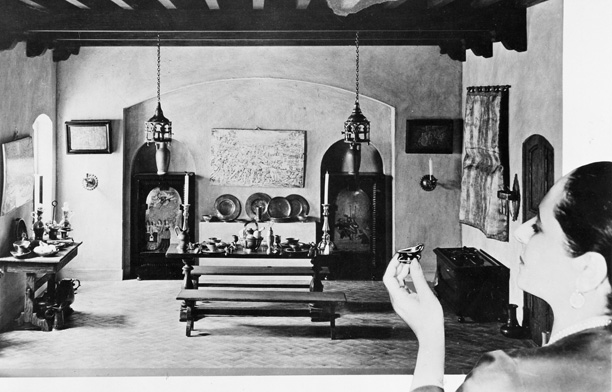

Just as Rubinstein invited the press into her lab—which she sometimes ingeniously described as her “kitchen”—she also projected herself as the gracious hostess showing off her elegantly decorated salons and luxurious homes in New York and Paris. These rooms, featuring bold colors and eclectic art displays, made for chic photo features in Life and Look and other magazines, as well as stunning backdrops for fashion shoots. Nor did she hesitate to invite herself into millions of American living rooms. In 1958, Madame herself appeared in 60-second television ads, in which she (or rather, the mellifluous Russian actress dubbing her voice) intoned, “I’m Helena Rubinstein. Give me just 10 minutes of your time and I’ll make you 10 years younger.”

It was this illusion of youth and beauty that made Rubinstein’s fortune and gave her power. She sold her customers as much through her own carefully crafted celebrity as through persuasion. In this sense, she was a visionary of the business world that surrounds us today. It is overreaching, though, to state as an exhibition wall text does that:

Art and cosmetics embodied Rubinstein’s overarching dual enterprise: to establish a correspondence between modern art and personal beauty, both of which she felt should be interpreted individually and subjectively.

Her embrace of modern art was sincere, but Rubinstein’s patronage was an outgrowth of her first passion—the business of boosting the bottom line—not the other way around. As with everything in Rubinstein’s life, art was part of her brand, and the luxury in which she surrounded her customers was part of the illusion she offered.

I’m also given pause by Mason Klein’s argument that Rubinstein empowered women by encouraging them to take charge of their images through their own choices and use of cosmetic products. If so, it was, at best, a by-product of her canny advertising and steady focus on building a business empire based on female consumers.

The exhibition’s most provocative idea is that of make-up as a method of re-invention. That is also perhaps the most pertinent reason for revisiting the life of Helena Rubinstein—the consummate self-re-inventor—at a venue such as The Jewish Museum. Rubinstein never hid her Jewish heritage (much is made here of the fact that she never changed her last name) and she fended off anti-Semitism with vigor. When, for instance, she was rejected as a tenant by a swank Park Avenue residence that did not allow Jewish residents, she simply bought the entire building. But she was, at best, ambivalent about Judaism, whose religious practice she had abandoned early on. “Scarcely unaware of her ethnicity,” Klein writes, “Rubinstein nevertheless allegedly also made disparaging comments about Jewish taste or certain neighborhoods . . . as ‘too Jewish.’”

This uneasiness, caught between ethnicity (to use Klein’s word) and mainstream taste, suggests, among other things, an intriguing clue to the lifelong rivalry between Rubinstein the immigrant Jewish upstart and her cosmetics competitor Elizabeth Arden. Arden also came from modest origins, but her Anglo-Saxon looks and lineage allowed for a more immediately acceptable mainstream image.

In some ways Helena Rubinstein’s life story is emblematic of 20th-century diaspora success. She acquired, incorporated, and layered adaptation upon adaptation from each new world she entered. She did so with a hungry zest to succeed, and she successfully built an empire. But after her death, it all crumbled. Her business was sold, her massive collections auctioned and dispersed to museums and private buyers around the world. It is not the least of the accomplishments of Mason Klein and The Jewish Museum to have brought so many of those objects back together again.

From this perspective, the rise and fall of Helena Rubinstein, the woman and the brand, approaches tragedy. But The Jewish Museum’s excellent exhibition commands less despair than wonder. It demonstrates that beauty can be power, but it is also fickle, an illusion that inevitably fades.

Suggested Reading

A Plague on the Shores of the Sea of Galilee

The death of the Great Maggid in December 1772, a week before Hanukkah, was a crucial moment in the early history of Hasidic movement.

A Serious Comedy

In A Serious Man, the Coen Brothers found a way to address the realest of subjects—their own childhood, their own sense of Judaism—without sacrificing their style; they “grew up” without losing their humor.

The Lost Voices of Salonica

Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s prodigious research, a true labor of love, gives voice to the long-silenced Salonican Jews.

Homage to Mahj

A traveling exhibit attempts to explain the Jewish fascination with Mah Jongg, a favorite past-time of mid-century Jewish suburbia, Jewish country clubs, and Catskill resorts.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In