The Lost Voices of Salonica

Neither my father—born Jewish, eventually a Spanish citizen, and a Roman Catholic convert—nor his brother—also eventually a Spanish citizen but never converted—ever really spoke about their experiences during World War II. My father spent the war’s last year, when the Germans occupied Athens, in the relative comfort of the basement of the Spanish embassy. My uncle was sent to Bergen-Belsen, along with his wife, their daughter, and her fiancé. All four survived.

I began to understand my father’s silence and his total deference to his brother when I watched Claude Lanzmann’s Shoah years ago and saw someone who had been spared the camps describe the searing guilt he felt toward those who had returned from them. And I began to understand my uncle’s reticence when I read Sarah Abrevaya Stein’s new history of the Levy family from its origins in 18th-century Salonica to their gradual dispersal across the globe. She writes that those “who struggled back to Salonica from Poland on foot found themselves spurned, and even physically threatened, by Jews who had come out of hiding.” Stein describes a woman who, as late as 1957, was considered an unsuitable match for her fiancé, “since she had survived the war in Bergen-Belsen and [her fiancé] had survived in hiding”—hiding not in an embassy but in the mountains, in caves, or in attics, in constant danger, as were those who dared to help them. The relationship between my father and his brother may have been mediated by emotions beyond guilt of which they could not speak. Until recently, on a personal, social, and national level, a wall of silence separated the history of the Jews of Salonica from the history of the Aegean port city that was their home for more than 400 years, since the expulsion from Spain and Portugal. (While the majority of Jews living in Salonica were the descendants of these Sephardic refugees, “Romaniote” Jews have lived in Greek territories, including mainland Greece, since roughly the time of Alexander the Great, in the fourth century BCE).

Family Papers: A Sephardic Journey Through the Twentieth Century, along with several other recent studies,breaks through the silence, which for much of the second half of the 20th century was maintained by the reluctance of Greeks, especially the non-Jewish inhabitants of Salonica, to acknowledge its rich, ultimately tragic Jewish history. The scholarly work of Stein and others complements the civic efforts of Yiannis Boutaris, until recently the mayor of Salonica, to get the city to acknowledge its past. Stein’s Family Papers is an extraordinary work of historical research, but it is much more personal, even intimate, than most scholarship. The book follows a single family, beginning with Sa’adi Besalel Ashkenazi a-Levi (1820–1903), who left his descendants a memoir of his life under the Ottomans. Sa’adi wrote in Ladino—the main language of Salonica’s Jews until French began to replace it in the early 20th century—in the 1880s. His small notebook passed through the hands of four generations of Levys. It traveled with them from Salonica to Paris to Rio de Janeiro and finally found its way to Jerusalem, where it still resides.

Sa’adi’s memoir is the first written record kept by this remarkable far-flung family, whose members were, despite the distances and the difficulties and disruptions, in more or less close, if often interrupted, touch with each other. They exchanged scores of letters that sketch a history not only of their own family but of the times they lived in, their pleasures, their many sorrows, their loves and quarrels, their good and bad fortunes, and, perhaps above all, their attempts to adjust to a modern world that had not been at all what they had anticipated.

Although she builds on the work of others, Stein’s original research has been nothing less than prodigious, locating archives and descendants in Greece, Portugal, Spain, France, Britain, Israel, India, Brazil, and Canada. (Sa’adi had 14 children, and many of them had large families of their own.) She has deciphered letters and documents in eight languages to tell the story of this emblematic Jewish family.

Sa’adi Besalel Ashkenazi a-Levi was personally religious but a liberal modernizer who, among other things, brought the first serious printing house to Salonica. He published a stable of Ladino and French newspapers that sometimes caused him serious trouble with religious authorities. In 1874, when he editorialized against the rabbinical tax on kosher meat, he was excommunicated by the local authorities, along with his young son (on the “trumped up charges of smoking on the Sabbath”). When that did not deter him, “the rabbi’s henchmen dragged and chased Sa’adi and [his eldest son Hayyim] through the streets of Salonica, a mob of five hundred at their heels.” Stein goes on to re-create the scene:

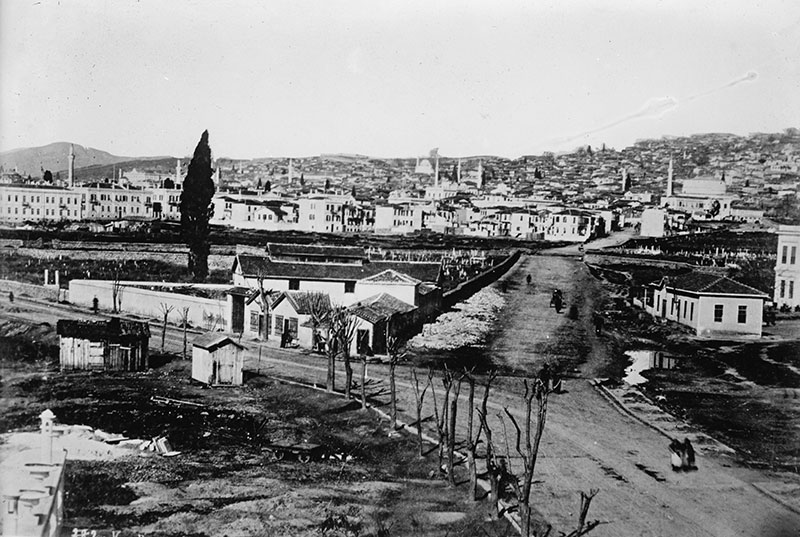

The city’s streets were then narrow and labyrinthine, lined with buildings in the Ottoman style. One can imagine their balconies alive with onlookers, witnesses to Sa’adi’s humiliation. The a-Levi family home was ransacked in the melee. Father and son were spared physical harm only after the intervention of a wealthy friend who succeeded in reasoning with the mob.

Although neither the excommunication nor the would-be lynching deterred him—“they fired a cannonball at me . . . I fired back in kind”—Stein says the experience traumatized Sa’adi and that his memoir was written “[o]ut of anger and a desire to clear his name.”

Salonica was unique in Europe because its Jewish inhabitants worked at all social levels. Jewish stevedores manned the large port (which was famously closed for business on the Sabbath), but there were also Jewish shopkeepers, industrialists, bankers, teachers, and so on, occupying every available professional niche. Although there were inevitable tensions with Greeks, Turks, and Bulgarians, the dynamic was very different from that experienced by Jews in other great European cities because, though they never ruled, they were never a minority either.

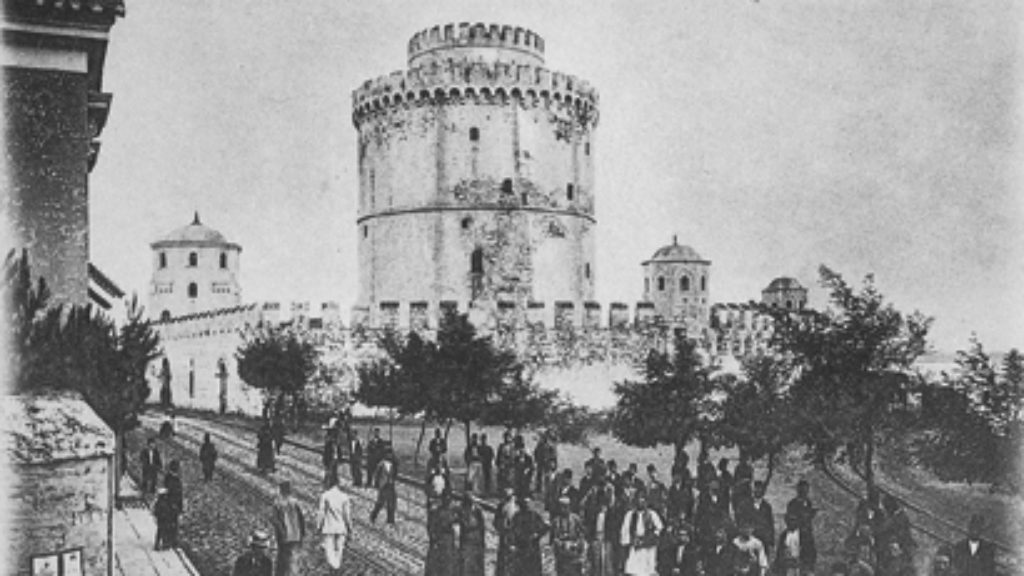

This changed with the incorporation of Salonica into the modern Greek state in 1913. When Salonica (renamed Thessaloniki in 1937) came under Greek control, the city’s Jews confronted a new situation: “What kind of nationals they became was a matter of choice. They could accept the state that formed around them, they could emigrate, or they could seek the protection of a foreign power.” Some became Greek citizens and others left, while some managed to get Spanish or Portuguese papers as the descendants of those who had been expelled in the 15th and 16th centuries.

The Great Fire of 1917 hastened the process, leaving Jews who still lived in the city’s center homeless. Although many of the Levys had already emigrated in the early years of the 20th century—to France for various businesses, to Manchester for textiles, to Brazil for imports and exports, even to India—more left as World War I approached and even more departed after its end as the city’s atmosphere became less and less hospitable. One and a half million Greeks had been relocated from Anatolia after the war with Turkey in 1922, and a huge number of them, primarily Greek Orthodox refugees, all in need of work and housing, descended on Salonica. Suddenly the remaining Jews were a minority in a city whose economic and cultural life they used to dominate.

Sa’adi’s daughter Rachel left and spent most of her professional life in various countries in the Levant as a teacher for the Alliance Israélite Universelle. His son David, who came to be known as Daout Effendi, had worked for the Ottoman administration and then ran the Ottoman-created Jewish Community under Greek supervision. He was chosen to welcome both the sultan of the Ottoman Empire and the king of Greece when they visited the city, at different times—different eras, really—before he was gassed at Auschwitz in 1943 at the age of 81.

Of the roughly 55,000 Jews who were still in the city when the Nazis arrived, in 1941, fewer than two thousand survived. Those who returned to Salonica found their houses occupied by the new immigrants or others who were unwilling to move.

Daout Effendi’s son Leon had already gone to Brazil and, despite an uneven temper which comes through in the letters, he was instrumental in keeping the family together after the war. He tried to locate those who were missing, to hold together those he found, and to help them financially as much as he could. He also visited Salonica several times after the war.

Inevitably, given the times, the family’s correspondence reflects the lives of its men more than its women—Sa’adi’s memoir doesn’t even mention the name of his first wife or his mother—but that doesn’t mean that there weren’t strong and independent women among the Levys. In addition to the teacher Rachel, there was Julie Hasson, Sa’adi’s great-granddaughter, who was “a maternal figure” to the Levys after the war. She was also the sister of the most controversial—not to say despicable—member of the family, Vital Hasson, whose shocking story Stein uncovered.

Vital was, to put it bluntly, a traitor and a war criminal. As head of the Jewish police in Salonica, he collaborated with the Nazis and robbed, raped, tortured, and killed his fellow Jews. After the war, he escaped to Albania before he was captured and returned by the British. He was tried along with his father, wife, and mistress. Although the Greek courts acquitted Vital’s family (who testified against him, along with many traumatized survivors), Vital himself—in the only such case of a Jew on record—was found guilty and executed.

Family Papers is more than a fascinating account of the Levys’ gradual transformation from Ottoman subjects into Westerners and their dispersal throughout the world. It is also an opportunity to hear a small but poignant set of voices break through the silence that we have faced so far about the Jews of Greece. Stein’s prodigious research, a true labor of love, gives voice to some of those who have been silenced.

Today Greece’s Jewish population hovers around a pitiful 5,000 (though antisemitism is rife), but every scholarly study, every discovery of a new memoir, every interview with a descendant of the city’s Jewish families, is proof that Thessaloniki’s present and future cannot be extricated from Salonica’s past.

Suggested Reading

Singing Gentile Songs: A Ladino Memoir by Sa’adi Besalel a-Levi

Sa'adi Besalel a-Levi's memoir of life in 19th-century Salonica provides a rare and intimate glimpse into a lost Ottoman Jewish world. Sa'adi was an accomplished singer and composer and a printer who helped to found modern Ladino print culture. He was also a rebel who accused the leaders of the Jewish community of being corrupt, abusive, and fanatical. In response, they excommunicated him—frequently, capriciously, and, in the end, definitively—though with imperfect success.

Sephardi Lives: From Ottoman Salonica to Rosario, Argentina

Singing women spark indignation in Salonica, a change of seasons in Argentina requires rabbinic expertise, and Jews in the Ottoman army get fat and happy.

Passport Sepharad

The recent offers of citizenship by Spain and Portugal tap into a long, rich, and complicated Sephardi history of dubious passports, desperate backup plans, and extraterritorial dreams.

Jerusalem of the Balkans

In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in Salonica and declared that it was "the only Jewish labor city in the world." Now, because of an open-minded mayor and his nationalist opponents, this formerly Jewish city is experiencing a peculiar mix of Jewish memory and anti-Semitism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In