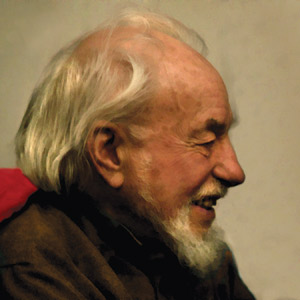

Intense Listening: The Poetry of Harvey Shapiro

In “The Distance,” a poem from Harvey Shapiro’s posthumous collection, he writes:

Prayer, as in:

my silence approaches

God’s silence.

The distance to be covered

is so immense

that there is time

to live my life

peacefully.

The lines are all the more poignant when one knows they were written during the poet’s final, ailing years. His vision, much like the poem’s concluding line, strains under the poem’s weight.

Shapiro’s poem bounced around in my head last Rosh Hashanah, and I imagine that it will this year as well. Standing in a small campus congregation, the singing and mumbling all around me surrounded Shapiro’s lines like a tenacious, contradictory commentary. Doesn’t the idea of praying with silence run contrary to everything I know about Judaism? Part of the traditional congregation’s joy is its noisiness, a cacophony of voices, sacred language running in counterpoint to shuffling, children’s squeals, barely stifled laughter in the back rows. Even the “silent prayer” is supposed to be whispered.

Harvey Shapiro, who grew up in an observant Jewish family, was a connoisseur of distances and silences. In another poem in this collection, an unbridgeable gap is also a metaphor for the poet’s relationship to his life’s work:

Writing, to put distance

between myself

and what I have written.

So I am free to start another life.

Though “another life,” for Shapiro, certainly meant another moment of inspiration, the distance, as in the previous poem, is not an impediment. It is as if poems, like years, build up, each next one rising toward a wider field of vision, another range of

possibilities.

A city poet, Shapiro spent much of his life working for The New York Times—the last decade as the deputy editor of The New York Times Book Review. He wrote his poetry at night, but his worlds did not contradict one another, as he put it in a poem from an earlier collection:

I am on the lookout for

A great illumining,

Prepared to recognize it

Instantly and put it to use

Even among the desks

And chairs of the office, should

It come between nine and five.

And indeed, like other great New York City poets—Walt Whitman, Frank O’Hara—Shapiro casually plucked moments of illumination from amid the city’s most unexpected settings, be it the chairs of the office, side streets of Brooklyn Heights, subway cars, or even the dreaded Long Island Expressway. Shapiro’s language and choice of imagery, too, are often informed by his wry sense of humor, familiar to any New Yorker. An untitled two liner from A Momentary Glory runs: “A bird in a tree said Debit debit. / Another day lost in anger.”

Shapiro’s humor—even in this final collection—may lead one to mistake him for a comic poet. But no matter how ironic, the poems nearly always carry a sense of spiritual inquiry and contact with personal darkness. “Mother of Invention” opens this way: “On my desk are the bills from the living / and in my sleep are the bills from the dead.”

Shapiro spoke of owing a debt of influence to the Objectivist poets, a diverse, mostly Jewish group of Modernists. Louis Zukofsky famously framed their project as “An integral / Lower limit speech / Upper limit music.” In an interview, Shapiro said that such insistence on vernacular language pointed him toward “a belief in the healing power that resides in the eye’s ability to see the world and the belief in that world . . . the belief that words don’t point to words but that words point to real things in the world.” Shapiro was deeply influenced by another Jewish Objectivist, Charles Reznikoff:

Reznikoff had a special meaning for me probably because I was very interested in Jewish subject matter. When I began I wrote a kind of academic poetry, looking back on it now. Then, in an attempt to get in touch with my childhood, I got interested in Jewish subject matter. I was a kid who spoke Yiddish before I spoke English. When I went back to mine that childhood material, I began to write poems that came out of my tribe.

In one of the early collections, Shapiro’s poetry gives voice to his tribal poetics:

. . . Greek redactions of the text

Stalled at the Tetragrammaton.

And violent in archaic script

The name burned upon parchment—

Whence springs the ram to mind again

From whose sinews David took

Ten strings to fan upon his harp.

So that the sacrifice was song,

Though ash lay on the altar stone.

The last line plunges the poem into ambiguity: If the sacrifice is song, where does the altar’s ash come from? This isn’t about art as an ideal sacrifice; neither is it an easy opposition between Jew and Greek. The terse harshness of the lines and the visceral string of words “violent . . . burned . . . sinews . . . sacrifice” stem from the burning need to speak and, through speech, to burn.

In Shapiro’s work, the desire to cut through to life’s essence is confessional, as in an early poem titled “The Intensity”:

When you think over what she said and what you said

The spaces begin to get larger until they modulate

Into silence. You stand there staring at each other

With no balloons floating the words, no

Captions, only the intensity of sight making

A language to scare anyone interested in communication

Or believing that two human beings can connect.

Unlike the distances valorized in other poems, this is a still life of disappointment. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to the poet, perhaps even requiring the invention of a new language, not to communicate but to dissolve communication. In the “Sayings of the Fathers”:

You think there must be more

To it than this—

A narrow examination

Of a life

A secret poring over books

A listening

For whatever stirs

An intense listening.

Perhaps, after all, that’s what the poet’s silence is: “an intense listening.” As in “Distance,” here too each line of the poem is terse and slow and prayer-like in its cadences.

Like Zukofsky and Reznikoff, Shapiro was born into a Yiddish-speaking home and came to American English with an outsider’s perspective and voraciousness. It is for that reason that the urge towards a simple and commonplace vocabulary seems all the more intentional for this Ivy League–educated poet. In his final collection, linguistic disarmament reaches an apex and appears to be a spiritual rather than programmatic effort—a purification ritual of sorts. This puts one in mind of another unlikely Jewish advocate for simplicity, a thinker whose name and thoughts appear continuously throughout Shapiro’s decades’ worth of writing: Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav, who described simplicity as “higher than all else.” For Rabbi Nachman, it was a hard-earned simplicity, the sort that hones one’s words the way fasting hones the body.

The closing poem in this collection, Shapiro’s last, is “Psalm”:

I am still on a rooftop in Brooklyn

on your holy day. The harbor is before me,

Governor’s Island, the Verrazano Bridge

and the Narrows. I keep in my head

what Rabbi Nachman said about the world

being a narrow bridge and that the important thing

is not to be afraid. So on this day

I bless my mother and father, that they be

not fearful where they wander. And I

ask you to bless them and before you

close your Book of Life, your Sefer Hachayim,

remember that I always praised your world

and your splendor and that my tongue

tried to say your name on Court Street in Brooklyn.

Take me safely through the Narrows to the sea.

Suggested Reading

Jews on the Loose

If fame is when everyone understands it is you when only your first name is mentioned, Groucho (Marx) certainly qualifies.

Chaim Grade: Portrait of the Artist as a Bareheaded Rosh Yeshiva

Grade attempted to perform the impossible: to undo in literature what had occurred in history and revive the dead of Jewish Vilna.

Harlem on His Mind

Many Harlem churches that were once synagogues have been torn down to make way for apartment buildings with all the latest amenities.

Letters, Summer 2022

Orthodox Lens; Kafka's Gimel; True Crime or Conspiracy Theory?; Of Censorship and Naughty Boys, and more

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In