New Gleanings from an Old Book

This summer in Alon Shevut, a community in the Etzion Bloc, south of Jerusalem, Lent will once again meet Mardi Gras. Every year here, the Herzog Academic College hosts its annual five-day seminar on the study of Tanakh, the Jewish Bible, during the week before Tisha b’Av. This is a time when the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple is traditionally commemorated by abstaining from meat and alcohol, from leisure activities like swimming and vacationing, and even from bathing and shaving. Despite this sobriety, at the seminar people are always excited, enjoying the company of old friends, teaching colleagues, and fellow Tanakh aficionados as they peruse the new books and compare notes with friends who have attended a different one of the seven lectures offered in each time slot (more than 200 lectures take place over the course of the week).

Grandmothers and their grandsons sit together, taking notes and debating subtleties. Charismatic teachers pack the lecture halls and are treated like rock stars as they roam the corridors. Innovative scholars test out new ideas, happily anticipating the sparring that will ensue when the knowledgeable audience begins to push back. What began humbly a quarter-century ago as a continuing education program for a hundred of the college’s alumni now boasts more than 5,000 participants who come from all over Israel, as well as North America and Europe.

The seminar is a visible expression of the explosion of biblical commentary that has emerged in “the Gush,” as Herzog College, the Beit Midrash for Women–Migdal Oz, and their parent institution, Yeshivat Har Etzion, are collectively known, over the last four decades. These institutions have come to be identified with a distinctive new derekh ha-limud (way of learning) in their approach to the Bible. This provides an important shared vocabulary of study, but what allows this intellectual subculture to take root and thrive has been its inclusion in the beit midrash, the noisy, boisterous, uniquely Jewish “house of study.” Even if one were to conclude, as some academic Bible critics do, that Gush Tanakh is merely religiously correct, watered-down pseudo-scholarship that avoids examining or undermining orthodoxies, one must still understand it as an extraordinary and surprising phenomenon that has not been replicated in other circles of Jewish learning.

The beit midrash of Yeshivat Har Etzion is, in most respects, like that of any other large, traditional yeshiva. Each student has barely enough shelf space for a small personal reference library consisting of a compact Babylonian Talmud, a small set of Maimonides’ code of Jewish law, several volumes of commentary on topics and tractates under study, perhaps a few ethical or philosophical treatises, and a one-volume Tanakh. This is not rare in itself. The Talmud often cites biblical verses, and meticulous students in every yeshiva are in the habit of looking up the verse to read and understand it in context.

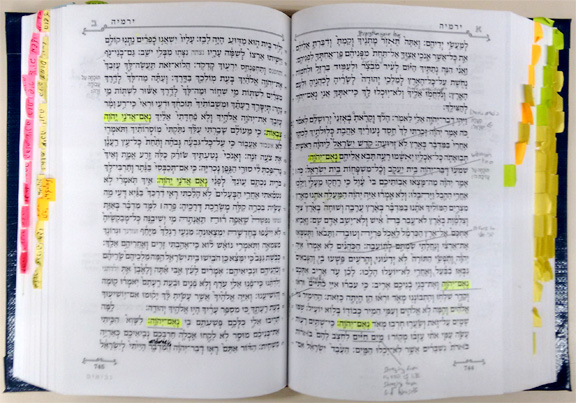

In this beit midrash, though, the Bibles are easier to spot as they inevitably have a bunch of color-coordinated Post-it tabs sticking out of the margins. Opening to one of the marked pages reveals a complex network of crisscrossing lines, highlighted keywords, nested brackets that stress the structure and topography of the biblical verses, and succinct notes that send the reader to a similarly themed, structured, or worded section of Tanakh. A student who sits nearby will, inevitably, have an alternative reading of the same segment, and the disagreement between the two of them may stem from disagreements between their respective teachers who have hashed out their exegetical differences in the beit midrash itself or in pamphlets and journals published in the Gush. The same thing is happening nearby at the yeshiva’s sister institution for women, Migdal Oz.

That is, Tanakh study in the Gush has partially displaced the Talmud at the heart of the yeshiva’s discourse. This is much more radical than outsiders may realize, for study of the Bible for its own sake, and in particular the study of its literary structures, has never been a central feature of the yeshiva curriculum. This innovation is a legacy of the Gush’s founder, Rabbi Yehuda Amital (see “The Audacity of Faith,” Fall 2011), who insisted from the outset that Tanakh be part of the yeshiva’s curriculum. Two of the first students that Rabbi Amital attracted to his new yeshiva were Rabbi Yaakov Medan and Rabbi Yoel Bin-Nun; their debates over biblical narrative became legendary within the yeshiva. They are remembered as arguing over key biblical narratives such as Joseph’s concealment of his identity from his brothers or David’s relationship with Bathsheba like heavyweight prizefighters, throwing prooftexts at each other in the beit midrash instead of punches.

Bin-Nun, the elder of the pair, was born to Hebrew philologists and came to the Gush after studying at the Merkaz Harav Kook yeshiva, where he had been imbued with the notion that Tanakh and the Land of Israel are metaphysically inseparable. His subsequent studies of Tanakh attempt to reconstruct the real-world settings in which biblical dramas unfold in a way that is far from the bookish, often hagiographical spirit of much rabbinic commentary. His preferred mode of teaching has been on-site, often on an archaeological dig. His interpretations often fly in the face of all prior Jewish interpretation, though he is just as willing to disagree with present-day archaeologists and academic scholars as with classical commentators. Medan came from a similar intellectual background; his father was a noted Hebrew grammarian. But unlike Bin-Nun his creativity is generally exercised in defense of the traditional commentators. One often finds him connecting the dots between apparently stray statements from across the rabbinic spectrum to demonstrate how seemingly fanciful interpretations emerged from straightforward inquiries into the biblical text. Though reluctant to offer interpretations that fly in the face of traditional exegesis, he is not dogmatic. Rather, he exploits textual gaps and quirks to imagine entire dialogues and scenes as he attempts to show how midrashim emerge from a deep engagement with the straightforward meaning of the text.

Another influential personality in the yeshiva’s early years was Rabbi Dr. Mordechai Breuer. A friend of Amital’s, he joined the yeshiva’s faculty to head its Tanakh program. As the scion of a major German Orthodox rabbinic family, his brilliance, pedantry, and self-certitude were virtually a birthright. At the Gush, he argued that the Torah should be read as a composite document—not because of multiple authorship, but because God’s truth is irreducible to a single human perspective. What began as debates in the beit midrash spilled over into the very first volumes of Herzog College’s quarterly journal on the study of Tanakh, Megadim, where, under Breuer’s editorship, the back-and-forth between Medan and Bin-Nun would unfold over multiple issues. They engaged with the biblical text, but more importantly, they engaged with each other, and in doing so they engaged with their students and audiences, drawing them into the drama of their debate.

The nascent movement got a boost in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when it began taking inspiration from academic scholars who were studying the poetics of biblical narrative. Scholars such as Meir Sternberg at Tel Aviv University and Robert Alter at the University of California, Berkeley, tended to bracket the traditional questions of academic biblical criticism—who wrote this?—in favor of literary questions—what does it mean?—which was conducive to the religious and intellectual environment of the Gush. By this time, Amital was sharing leadership of the yeshiva with Rabbi Dr. Aharon Lichtenstein, who held a doctorate in English literature from Harvard (he passed away in April of this year). In fact, before coming to Israel, Lichtenstein had delivered a lecture in the early 1960s at Yeshiva University’s Stern College for Women calling for a distinctively Orthodox literary study of the Bible. The content of that lecture was prescient, but so was its context: Women are notably present and participate at every level of the intellectual discourse generated within the Gush.

The unique religious and intellectual environment of the Gush cannot be divorced from the broader context of post-1967 Israel. One can only ignore Tanakh for so long in Israel. The establishment of a Jewish state after millennia of statelessness, followed 19 years later by the resounding victory in the Six-Day War, left Israel in possession of almost the entire biblical land of Israel, including the Etzion Bloc itself, which had been the site of several Jewish settlements that fell on the eve of Israel’s independence.

The Gush Tanakh phenomenon is distinctly Israeli, distinctly religious Zionist in fact, but it has been increasingly influential in North American Modern Orthodox communities. A generation ago, English-speaking students at the Gush would likely have encountered the approach in classes and on Bible-in-hand hikes with Rabbi Menachem Leibtag. Leibtag challenged students to look at the broader themes, literary structure and composition, and geographical and historical setting of extended passages and even entire books of the Tanakh. His classes were among the first offerings of the Virtual Beit Midrash (vbm-torah.org), the Gush’s website established in 1994. Within a few years, the VBM was hosting an impressive array of courses, as well as translations of particularly significant articles from Megadim.

Recently, Yeshivat Har Etzion, together with Jerusalem’s Maggid Books, an imprint of Koren Publishers, launched its ambitious Studies in Tanakh series with the goal of producing book-length studies of each biblical book. Most of these books also began as VBM courses, including the fourth and most recent installment, Dr. Yael Ziegler’s Ruth: From Alienation to Monarchy.

Ruth, one of the shortest books in all of Tanakh, has a simple plot: A man from Bethlehem moves with his family to Moabite territory to ride out a famine in Judea, his two sons somewhat scandalously marry Moabite women, and all the men subsequently die. The widowed matriarch, Naomi, decides to go back to Judea and discourages her daughters-in-law from accompanying her. One accedes, while the other, Ruth, famously declares her loyalty: “Do not urge me to leave you, to turn back and not follow you. For wherever you go, I will go; wherever you lodge, I will lodge. Your people shall be my people, and your God my God. Where you die, I will die, and there I will be buried. Thus and more may the Lord do to me if anything but death parts me from you.” (Ruth 1:16–17). Once back in Bethlehem, Ruth goes gleaning in the fields as a pauper to feed herself and Naomi, and she encounters the benevolence of Boaz, a relative and potential redeemer. Their hunger temporarily abated, Naomi cooks up a scheme for Ruth to seduce Boaz, which Ruth follows. After overcoming some legal hurdles, Ruth and Boaz marry, and their great grandson is none other than King David.

Ziegler’s command of the body of interpretation of Ruth, from midrashic, to medieval Jewish exegetes, to contemporary scholars, is everywhere apparent, but she tends to relegate technical discussions to the notes. Nevertheless, her book is not a quick or easy read. Readers will have to work to follow her interpretive arguments, but helpful charts and diagrams abound, and the payoff is more than academic.

In Ziegler’s presentation, the book of Ruth is a contrast and corrective to the book of Judges. The opening verse sets the events of Ruth in the era of the Judges (Ziegler barely addresses when the book was composed, noting that scholarly opinion is divided while referring interested readers to the relevant studies), and indeed, the book of Ruth is placed immediately after Judges in the Christian canon. Whereas Judges describes an Israelite society plagued by anarchy, godlessness, and self-

centeredness, Ruth offers a way out, a recipe for overcoming dissolution and building toward a cohesive and godly society. Ziegler supports this thesis by drawing a series of linguistic and thematic parallels between the book of Ruth and other biblical books, particularly Genesis and Judges.

In Genesis, Abraham and his nephew Lot part ways. Abraham becomes the bearer of God’s covenant, calling out in God’s name and paving the way for a just and righteous society. Lot moves to Sodom and, upon its destruction, continues its legacy by siring, through his own daughters, Ammon and Moab, tribes that are later deemed unfit to intermarry with Israelites on account of their refusal to offer the Israelites bread and water during their desert sojourn (Deut. 23:4–5). In the era of the Judges, however, Israelite society is itself inhospitable, xenophobic, promiscuous, and violent—downright Sodom-like. Ruth leads Israelite society in the opposite direction. As Zeigler writes:

Ruth’s journey to Bethlehem is indeed a “return”; it represents the closing of the circle begun with Lot’s abandonment of Abraham in Genesis 13. That event leads to the creation of the nations of Ammon and Moab, the spiritual heirs of Sodom, who are steeped in cruelty and immorality. Lot’s descendant, Ruth the Moabite, returns to the path of Abraham and becomes a paradigm of hesed [kindness] and modesty . . . She accomplishes much more than that. Ruth produces the Davidic dynasty, which is the vehicle for the nation’s return to the path of Abraham.

Interestingly, Ziegler treats the mother-in-law Naomi as the protagonist of the book, but not its hero. Whereas Ruth and Boaz are entirely positive characters, in Ziegler’s reading Naomi is only somewhat unsympathetic but redeemable—like Israelite society as a whole. The turning point, in Ziegler’s reading, occurs when Naomi responds to the kindness of Boaz and Ruth. Naomi’s acceptance at the end of the book is the inversion of her alienation at the beginning. (In the literary terminology enthusiastically adapted by the Gush school, the relationship between these two chapters is chiastic.)

Like commentators before her, Ziegler pays close attention to the names and epithets used in Ruth. An embittered Naomi (whose name means sweet) asks to be called Mara (bitter); the name of the redeemer who refuses to propagate the name and legacy of Ruth’s dead husband is named Ploni Almoni, the biblical equivalent of John Doe, and so on. On the other hand, there are subtleties that can easily be missed: Ruth herself is variously referred to as a Moabite girl, a daughter (by Naomi and by Boaz), Naomi’s daughter-in-law, and a virtuous woman. Ziegler carefully shows how these different descriptions indicate how Ruth is perceived by others and how those perceptions change throughout the book.

Ziegler points out two instances where the book itself registers surprise at fortuitous coincidences. When Boaz happens to visit the field where Ruth is gleaning, and when Ploni happens to pass by the city gate when Boaz wishes to arrange for Ruth’s redemption, the text employs the word “Hinei”—“Lo and behold!”—suggesting a literal deus ex machina. For Ziegler it is significant that these examples of indirect divine intervention are both in response to generous human initiatives, namely, Ruth’s offer to glean on Naomi’s behalf and Boaz’s offer to ensure Ruth’s redemption. In the socio-religious economy of Ruth, God’s bounty is bestowed through human kindness rather than divine miracles, that is, by humans acting in a godly manner.

Following Medan, Ziegler takes midrash seriously as exegesis and tries to understand what narrative gaps the rabbis were trying to fill with even their least tenable interpretations. For example, several midrashim condemn Naomi’s husband Elimelekh for abandoning his people during a famine when he could have sustained them with his wealth. As Ziegler notes, nothing in the text indicates that Elimelekh’s flight was motivated by miserliness or abdication of social responsibility. The most plausible reading of his flight to Moab is simply that he was fleeing a famine.

Ziegler suggests that in their disapproval of Elimelekh, the sages are reflecting on his choice to relocate to Moab. When earlier biblical figures leave Israel in times of famine it is always for Egypt, where one can always count on the Nile’s waters, not Moab, whose climate is like Israel’s. Moreover, Moab is the land of Sodom’s heirs. And to turn to Moab is, morally speaking, to follow Lot. The sages thus connect Elimelekh’s relocation with the book’s broader theme of return from the path of Lot to the path of Abraham.

Ziegler never mentions current events, yet it is clear that she intends her book to be read with an eye on contemporary Israeli society. Questions of selfishness and tribalism, treatment of proselytes and immigrants, cohesiveness and social responsibility, leadership and exploitation are once again relevant in this old-new land, and its people are once again turning to Tanakh for moral insight. Ruth: From Alienation to Monarchy shows how literarily and morally rich the biblical book of Ruth is, undercutting all attempts to reduce it to an apologetic attempt to domesticate nasty rumors about King David’s lineage, mere polemics against xenophobia, or “mere” anything else. Yael Ziegler has written a commentary that exemplifies the unique combination of literary analysis, theology, and loyalty to rabbinic tradition of the new Gush method of Bible study.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Lives in Translation

The elegant essays in Hillel Halkin's new book are the fruit of a lifetime devoted to Hebrew literature.

Pro-Creation

Economist Bryan Caplan thinks parents “overcharge” themselves when it comes to investing in their children. Glückel of Hameln knew better.

The Other Bernstein

Late August 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth and the first Yahrzeit of his brother, Burton, who wrote an incredible family memoir.

The Nazi Rosetta Stone

The interagency task force meeting at an elegant suburban estate was like any other such meeting, except for its agenda: the “final solution.”

ravnatih

Kudos to Elli Fischer on his excellent review essay of Yael Ziegler's wonderful new volume on the book of Ruth and his overview of the Gush Tanakh phenomenon, as he labels it. One small addition. R. Fischer notes that while this phenomenon is an Israeli religious-Zionist one it has come to influence the American Modern-Orthodox scene through the exposure that many students (who later became rabbis and educators) had to educators such as R. Menachem Leibtag at Gush and through reading essays of this type on the VBM through the internet. This is certainly a large part of the story.

However, we should also note the indigenous American phenomena of educators and scholars such as R. Shalom Carmy (at YU) and R. David Silber (at Lincoln Square Synagogue and Drisha) amongst others who in the 1970's and 1980's taught generations of students and laypeople and exposed them to the literary-theological method here in the states that closely dovetails many of the methods and insights developed robustly by the Gush methodology. They brought the insights of close readers like U. Cassutto, B. Jacob, M. Weiss, R. Alter and many others to their students and coupled that together with their own literary creativity and vast knowledge of the rabbinic exegetical tradition to bear and guided students in pursuit of understanding peshuto shel mikra- the plain sense of the text-, psychological insight into biblical characters and over-arching themes in the text to the forefront of a serious and sophisticated study of Tanakh.