Playing the Fool

“Let’s talk about something more cheerful. Have you heard any news about the cholera in Odessa?”

That’s the famous ending of Sholem Aleichem’s 1904 story “Hodl,” about Tevye the Dairyman’s daughter who marries a communist and follows him into exile in Siberia. The story is a heartbreaking one, ending with a forced separation between a Russian-Jewish parent and child. But the agony buried within that final joke transcended literature after Sholem Aleichem’s death—when revolutionaries like Hodl’s husband actually succeeded in creating a new Russian regime that promised its Jews lives of integrity, seduced them into compliance, and ultimately ate some of the best of them alive.

The Soviet-Jewish experience took the form of a psychological horror story, brimming with suspense, double-crossing, and twisted self-blame. Its greatest horror came in the undoing of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, a board of prominent Soviet-Jewish artists and intellectuals established by Joseph Stalin in 1942 to drum up financial support from Jews overseas for the Soviet war effort. Two of the more prominent names on the JAC’s roster were Solomon Mikhoels, the director of the Moscow State Yiddish Theater, and Benjamin Zuskin, the theater’s leading comic actor. After promoting these people to the skies during the war, Stalin decided these loyal Jewish communists were no longer useful and charged them all with treason. Mikhoels was murdered first, in a hit staged to look like a traffic accident. Nearly all the others, including Zuskin and several renowned Yiddish writers, were executed by firing squad on August 12, 1952.

Just as the regime accused these Jewish artists and intellectuals of being too “nationalist” (read: Jewish), our long hindsight makes it strangely tempting to read this history and accuse them of not being “nationalist” enough—that is, of being so foolishly committed to the Soviet party line that they were unable to see the writing on the wall and were thus gobsmacked by Stalin’s deadly betrayal. Many works on this subject have said as much. In Stalin’s Secret Pogrom, the indispensible English translation of transcripts from the JAC show trial, Russia scholar Joshua Rubenstein concludes his lengthy introduction with the following:

As for the defendants at the trial, it is not clear what they believed about the system they each served. Their lives darkly embodied the tragedy of Soviet Jewry. A combination of revolutionary commitment and naïve idealism had tied them to a system they could not renounce. Whatever doubts or misgivings they had, they kept to themselves, and served the Kremlin with the required enthusiasm. They were not dissidents. They were Jewish martyrs. They were also Soviet patriots. Stalin repaid their loyalty by destroying them.

This is completely true and also completely unfair. The tragedy—even the term seems unjust, with its implied blaming of the victim—was not that these Soviet-Jewish artists and intellectuals sold their souls to the devil, though many clearly did. The tragedy, for which no one can be blamed but the relevant devil, was that integrity was never an option in the first place.

Of the many varieties of anti-Semitism, or anti-Judaism, that have plagued the Jews over the centuries, two recurrent general patterns can be identified by the holidays that celebrate triumphs over them: Purim and Hanukkah. In the Purim version, exemplified by the Persian genocidal decrees in the biblical book of Esther, as well as by more recent ideologies like Nazism and today’s many versions of radical Islam, the regime’s goal is unambiguous: Kill all the Jews. In the Hanukkah version, as in the 2nd-century B.C.E. Hellenized Seleucid regime that criminalized all expressions of Judaism, the goal is still to eliminate Jewish civilization. But in the Hanukkah version, this goal could theoretically be accomplished by simply destroying the civilization, while leaving the warm de-Judaized bodies of its former practitioners intact. For this reason, the Hanukkah version of anti-Semitism—whose appearances range from the Spanish Inquisition to the Soviet regime—often employs Jews as its agents. These “converted” Jews openly renounce whatever aspects of their Jewish identity are unacceptable to the relevant regime, proudly declare their loyalty to the ideology of the day, and loudly urge other Jews to follow them. These people are used as cover to demonstrate the good intentions of the regime—which of course isn’t anti-Semitic, but merely requires that its Jews publicly flush thousands of years of Jewish civilization down the toilet in exchange for the prize of not being treated like dirt or murdered. For a few years. Maybe.

After many episodes of Purim-style anti-Semitism on the steppes, and especially after the Holocaust, it is perhaps not surprising that so many Soviet Jews fell into the trap of not recognizing Hanukkah-style anti-Semitism when it first became apparent or of actively serving as the regime’s willing agents. In the wake of indiscriminate massacres ranging from Khmelnitzky to Petliura to Babi Yar (the latter two in their living memory), these people may well have found a certain appeal in the prospect of not being murdered, regardless of the cost.

For those artists who worked in Yiddish, the Soviet Union in its early years had the added attraction of apparently not treating them like dirt. In its quest to brainwash national minorities in the 1920s and 1930s, the regime offered unprecedented material support to Yiddish culture, paying for Yiddish-language schools, theaters, publishing houses, and more, to the extent that there were Yiddish literary critics who were actually salaried by the Soviet government. This support led the major Yiddish novelist Dovid Bergelson to publish his landmark 1926 article “Three Centers” about New York, Warsaw, and Moscow as centers of Yiddish-speaking culture, asking which city offered Yiddish writers the brightest prospects. Bergelson’s unequivocal answer was Moscow, a choice that resulted in his execution in 1952.

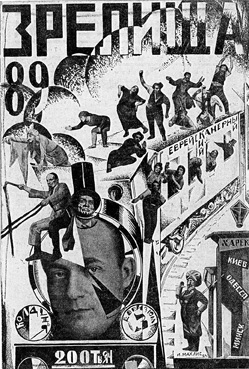

The reversal of Soviet-Jewish fortunes is occasionally presented as abrupt and unexpected, as in the Jewish Museum’s otherwise excellent exhibit on the Moscow State Yiddish Theater in 2009, where rooms full of beautiful Chagall murals and Yiddish films terminated suddenly in a dark room featuring a film of the funeral of the theater’s murdered director Mikhoels, with a voiceover announcing, “Theater is an ephemeral art.” (I couldn’t make this up.) But the truth is that from the beginning, Soviet support for Jewish culture came at a very particular, Hanukkah-style price: the extraction of its Judaism, down to the letters in which it was written. The regime went so far as to create a new, literally anti-Semitic Soviet orthography for Yiddish. This involved eliminating the alphabet’s variable final consonants (a mem at the end of a word looks exactly like a mem anywhere else) and making the spelling of all Semitic-origin words phonetic, so that a word like “Shabbat” (pronounced “Shabbes” in Yiddish), spelled since the Pentateuch as shin–bet–tav (“shin–beys–sav” in Yiddish), was now spelled “shin–alef–beys–ayin–somekh.” If the goal here weren’t spelled out clearly enough, one can see the process even more vividly in the repertoire of the government-sponsored Moscow State Yiddish Theater, which could only present or adapt Yiddish plays that denounced traditional Judaism as backward, bourgeois, corrupt, or even more explicitly—as in the many productions involving ghosts and graveyard scenes—as literally dead. As its actors would be, soon enough.

Enter Benjamin Zuskin, stage left.

Among the many scholarly tomes on Soviet-Jewish history, Ala Zuskin Perelman’s The Travels of Benjamin Zuskin, a memoir of the author’s father, is a breath of fresh air. Zuskin Perelman, who now lives in Israel, was only 14 years old when her father was arrested. But her book—first published in Hebrew and Russian in 2002, and newly available in English in a somewhat abridged form—is painstakingly researched in both Russian and Yiddish sources, and she grew up completely immersed in her father’s world. Her mother was also an actor in the Moscow State Yiddish Theater, and her family lived in the same building as Mikhoels, along with many other important Soviet-Jewish artists. In addition to seeing her parents perform countless times, she also witnessed the destruction of their world: She attended Mikhoels’s state funeral; witnessed the arrest of the Yiddish writer Der Nister, whose apartment was across the hall from hers; and was present when secret police ransacked her home in conjunction with her father’s arrest. We are accustomed by now to reading emotional memoirs of Holocaust survivors or victims written by their children, and, since the collapse of the Soviet Union, we are also accustomed to clinical reports of Soviet crimes extracted from archives opened in the past 20 years. But Zuskin Perelman’s book is a rare thing: an emotional recounting, with the benefit of hindsight, of what it was really like to live through the nadir of the Soviet-Jewish nightmare.

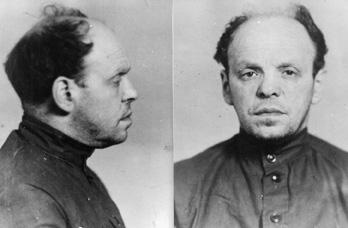

It’s as close as we can get, anyway. Benjamin Zuskin’s own thoughts on the topic are only available from state interrogations extracted under unknown tortures. (One typical interrogation document from his three years in the notorious Lefortovo Prison announces that that day’s interrogation lasted four hours, but the transcript is only half a page long—leaving to the imagination how interrogator and interrogatee may have spent their time together. Suffice it to say that another JAC detainee didn’t make it through the trial alive.) His three years in Lefortovo began when he was arrested in 1949 in a hospital room, where he was being treated for chronic insomnia brought on by the murder of his boss and career-long acting partner Mikhoels; the secret police strapped him to a gurney and carted him to prison in his hospital gown while he was still sedated.

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. In order to truly appreciate the loss here, one needs to know what was lost. And for that one needs to return to the world of Sholem Aleichem, the author of Benjamin Zuskin’s first role on the Yiddish stage, in a play fittingly titled It’s a Lie!

Benjamin Zuskin’s path to the Yiddish theater and later to the Soviet firing squad began in a shtetl comparable to those immortalized in Sholem Aleichem’s work, and part of this memoir’s beauty is the attention it lavishes on how the old world Zuskin came from animated his art. Zuskin, a religious child who was exposed to theater only through traveling Yiddish troupes and clowning relatives, experienced that world’s destruction: His native Lithuanian shtetl, Ponievezh, was among the many Jewish towns forcibly evacuated during the First World War, catapulting him and hundreds of thousands of other Jewish refugees into modernity. He landed in a secular secondary school in Penza, a Russian city with a Yiddish theater presence. In 1920, the Moscow State Yiddish Theater opened, and by 1921, Zuskin was starring alongside Mikhoels, the theater’s leading light.

In the one acting class I ever attended, I learned only one thing: Acting isn’t about pretending to be someone you aren’t, but rather about emotional communication. Zuskin, who not only starred in most theater productions but also ran the theater’s acting school, embodied that concept. His very first audition was a one-man sketch he created, consisting of nothing more than a bumbling old tailor threading a needle—without words, costumes, or props. It became so popular that he performed it to entranced crowds for years. This physical artistry, beautifully described in this memoir, animated his every role. As one critic wrote, “Even the slightest breeze and he is already air-bound.”

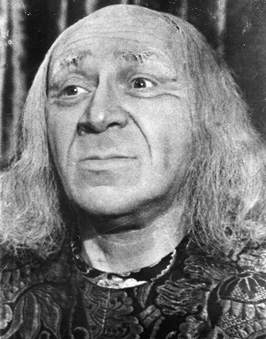

Zuskin specialized in playing comic figures like the Fool in King Lear—as his daughter puts it, characters who “are supposed to make you laugh, but they have an additional dimension, and they arouse poignant reflections about the cruelty of the world.” In an autobiographical essay included in the volume, Zuskin articulates this vividly. As he discusses his favorite roles, he explains that “my heart is captivated particularly by the image of the person who is derided and humiliated, but who loves life, even though he encounters obstacles placed before him through no fault of his own.” Unwittingly, Zuskin was pretending to be no one but himself.

The first half of this memoir seems to recount only triumphs, and students of Yiddish theater will find it indispensable. The theater’s repertoire in its early years was largely adapted from classic Yiddish writers such as Sholem Aleichem, I.L. Peretz, and Mendele Mokher Seforim. The memoir’s title is drawn from Zuskin’s most famous role: Senderl, the Sancho Panza figure in Mendele’s Don Quixote-inspired work Masoes Binyomin Hashlishi (Travels of Benjamin the Third), about a pair of shtetl idiots who set out for the Land of Israel and wind up walking around the block. These productions were artistically inventive, brilliantly acted, and played to packed houses both at home and on tour. Travels of Benjamin the Third, in a 1928 review typical of the play’s reception, was lauded by The New York Times as “one of the most originally conceived and beautifully executed evenings in the modern theater.”

The acclaim came at a price. Consider one of the theater’s landmark productions, I.L. Peretz’s surrealist masterpiece Bay nakht afn altn mark (At Night in the Old Marketplace), first performed in 1925. Zuskin Perelman accurately describes this dreamlike play as a “carnival of ghosts” with “a dying city and a graveyard coming to life.” Those who come back from the dead are not only misfits like drunks and prostitutes, but specific figures from shtetl life—cantors, Hasidim, synagogue beadles, and the like. Leading them all is a badkhn, or wedding jester—divided in this production into two mirror-characters played by Mikhoels and Zuskin—whose repeated chorus among the living corpses is “The dead will rise!” “Within this play there was something hidden, something with an ungraspable depth,” Zuskin Perelman writes, and then relates how after a performance in Vienna, one theatergoer came backstage to tell the director that “the play had shaken him as something that went beyond all imagination.” The theatergoer was Sigmund Freud.

Zuskin Perelman shares this anecdote only to show the theater’s caliber. But as we contemplate the theater’s trajectory toward doom—it was during this European tour that the theater’s famed director Alexander Granovsky defected to the West—it is worth considering why this performance so affected Freud. The production was a zombie story about the horrifying possibility of something that is supposed to be dead (here, Jewish civilization) coming back to life. In this way, this romantic work became a means of denigrating traditional Jewish life without mourning it. That fantasy of a culture’s death as something compelling and even desirable is not merely reminiscent of Freud’s death-drive, but emblematic of the self-destructive bargain implicit in the entire Soviet-sponsored Jewish enterprise. Zuskin Perelman beautifully captures this tension as she explains the badkhn’s role: “He sends a double message: he denies the very existence of the vanishing shadow world, and simultaneously he mocks it, as if it really does exist.”

This double message was at the heart of Benjamin Zuskin’s work as a comic Soviet-Yiddish actor, a position that required him to mock the traditional Jewish life he came from while also pretending that his art could exist without it. “The chance to make fun of the shtetl which has become a thing of the past charmed me,” he claimed early on, but later, according to his daughter, he began to privately express misgivings. The theater’s decision to stage King Lear as a way of elevating itself disturbed him, suggesting as it did that the Yiddish repertoire was inferior. “With the sharp sense of belonging to everything Jewish, he was tormented by the theater forsaking its expression of this belonging,” his daughter writes. Even so, “no, he could not allow himself to oppose the Soviet regime even in his thoughts, the regime that gave him his own theater, but ‘the heart and the wit do not meet.’”

In Zuskin Perelman’s telling, her father differed from his director, partner, and occasional rival Mikhoels in his complete disinterest in politics. Mikhoels was a public figure as well as a performer, and his leadership of the Jewish Antifascist Committee, while no more voluntary than any public act in a totalitarian state, was a role he played with gusto, traveling to America in 1943 and speaking to thousands of American Jews to raise money for the Red Army. Zuskin, on the other hand, was on the JAC roster, but seems to have continued playing the fool. His role in the JAC was comparable to a similar post he held on a Moscow city council, where his contribution was limited to playing chess in the back of the room during meetings.

Zuskin Perelman presents her father as a kind of tam, the classical Hebrew term for both a simpleton and an innocent. It is true that in trial transcripts, Zuskin comes out looking better than many of his co-defendants by playing dumb instead of pointing fingers. But was this ignorance or a wise acceptance of the futility of trying to save his skin? As Lear’s Fool says, “They’ll have me whipp’d for speaking true; thou’lt have me whipp’d for lying, and sometimes I am whipp’d for holding my peace.” Reflecting on her father’s role as a fool named Pinia in a popular film, she writes, “When I imagine the moment when my father heard his death sentence, I see Pinia in close-up . . . shoulders slumped, despair in his appearance. I hear the tone that cannot be imitated in his last line in the film—and perhaps also the last line in his life?—‘I don’t understand anything.’”

Yet it is clear that Zuskin deeply understood how impossible his situation was. In one of the book’s more disturbing moments, his daughter describes him rehearsing for one of his landmark roles, that of the comic actor Hotsmakh in Sholem Aleichem’s Blondzhende shtern (Wandering Stars), a work whose subject is the Yiddish theater. He had played the role before, but this production was going up in the wake of Mikhoels’ murder. Zuskin was already among the hunted, and he knew it:

One morning—already after the murder of Mikhoels—I saw my father pacing the room and memorizing the words of Hotsmakh’s role. Suddenly, in a gesture revealing a hopeless anguish, Father actually threw himself at me, hugged me, pressed me to his heart, and together with me, continued to pace the room and to memorize the words of the role. That evening I saw the performance … “The doctors say that I need rest, air, and the sea . . . For what . . . without the theater?” [Hotsmakh asks], he winds the scarf around his neck—as though it were a noose. For my father, I think these words of Hotsmakh were like the motif of the role and—I think—of his own life.

Describing the charges levied against Zuskin and his peers is a degrading exercise, for doing so makes it seem as though these charges are worth considering. They are not. It is at this point that Hanukkah anti-Semitism transformed, as it so easily can, into something closer to Purim anti-Semitism. Here this memoir offers us what thousands of pages of state archives can’t, describing the impending horror of the noose around one’s neck. Zuskin stopped sleeping, began receiving anonymous threats, and saw that he was being watched. No conversation was safe. When a visitor from Poland waited near Zuskin’s apartment building to give him a message from his older daughter Tamara (who was then living in Warsaw), Zuskin instructed the man to walk behind him while speaking to him and then to switch directions, so as to avoid notice. When the man asked Zuskin what he wanted to tell his daughter, Zuskin “approached the guest so closely that there was no space between them, and whispered in Yiddish, ‘Tell her that the ground is burning beneath my feet.’” His arrest under sedation in his hospital gown seems almost merciful by comparison. Yet there was no mercy in what followed and also no guilt. It is true that no one can know what Zuskin or any of the other defendants really believed about the Soviet system they served. It is also true—and far more devastating—that their beliefs were utterly irrelevant.

Writing about Sholem Aleichem’s work, Zuskin once noted that “Comic and tragic, laughter and tears, these two opposites are woven together and they cannot be separated.” This idea of laughter-through-tears has become such a platitude in describing Yiddish culture that we accept it as though it were a feature of all humor, as though the comic and the tragic were always interwoven, as though it were normal. It isn’t, of course. But in the theater of Hanukkah-style anti-Semitism, where absurdity piles upon absurdity until even 63 years later we are still debating the degree to which these Jews deserved to be executed by firing squad, it is disturbingly consistent.

The Travels of Benjamin Zuskin is not tragic. It is heartbreaking. It is also deeply moving and even more deeply disturbing—particularly today, as one considers how anti-Semitism of both varieties has once again become normal and how, in country after country, Jews are once again being called upon to play the fool.

But perhaps we can instead talk about something more cheerful. Have you heard any news about the cholera in Odessa?

Suggested Reading

“Repent, Repent”

In his new book, How Repentance Became Biblical: Judaism, Christianity, and the Interpretation of Scripture, David A. Lambert argues that repentance, as we understand it today, is absent from the Hebrew Bible.

The Kibbutz and the State

How the position of the kibbutz in Israeli society has changed, and why.

Letters, Fall 2021

We and I; It's a Novel: An Exchange

“Jacob Gazed into the Distant Future”

In Jacob & Esau: Jewish European History Between Nation and Empire, Malachi Haim Hacohen provides a dense but lucid account of how the history of this typology of sibling rivalry unfolded, first in the later books of the Bible and then, following the invention of a linkage between Edom and the Roman Empire, in rabbinic literature, and, finally, in later Jewish and Christian writings, down to modern times.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In