Melting Pot

Joan Nathan’s Quiches, Kugels, and Couscous: My Search for Jewish Cooking in France doesn’t have a very French title. Quiche is more American fantasy than true French staple; no one eats kugels in France nowadays; and the French do not speak of “cooking” but rather of “cuisine” or “the table.” But such quibbles should not prevent one from digging into Nathan’s story of Jewish-French culinary culture and its development. Probably America’s leading writer on Jewish food, Nathan (who, I should mention, consulted with me briefly while writing the book) is especially well known for her historical cookbook, Jewish Cooking in America, but she also has experience with French cuisine going back to her student days in the 1950s. In her frequent travels through France, where her family has roots, she has collected recipes, stories, reflections, pictures, and historical data on the local Jewish cuisine.

France is one of the great centers of Jewish cuisine for two reasons. The first, and most obvious, is that France is one of the very few countries in which eating is less a corporeal necessity than a culture unto itself. Indeed, the Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin, the 18th-century codifier of French gastronomy, even banned the word “feed” (“Animals,” he wrote, “are fed, man eats”). French Jews had to adapt to such mores. The second reason is the melting pot that is French Jewry, which is now the third largest Jewish population center, second only to Israel in its diversity. In the past two centuries, France has seen large-scale immigration from both Central and Eastern Europe, North Africa, and the Near East. Each group of newcomers has worked to preserve its traditions in two key realms: liturgy and food.

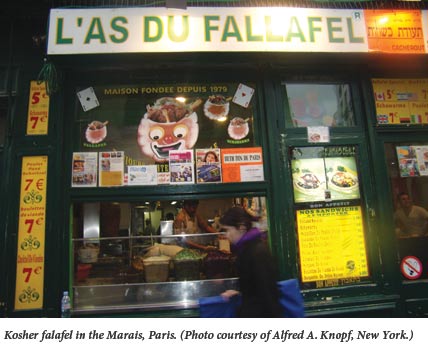

In recent years, French Jewry has also made a massive and unexpected return to religious observance, creating a new demand for kosher cuisine. According to the Shamash worldwide database, France now boasts 379 kosher restaurants, for a Jewish population of about 500,000. (By contrast, the United States has 5.5 million Jews but only 1510 kosher restaurants). Unfortunately, Nathan’s vision of France and French-Jewish cooking has not caught up with these developments. She scants the vast array of kosher restaurants that have transformed Jewish life in France, bringing French-Jewish food to prominence and raising its standards of quality to unprecedented levels. Her list of eighteen notable restaurants includes only three certified kosher restaurants. A fourth restaurant, which she describes as kosher, claims indeed to be so, but was never certified by any rabbinical authority.

In recent years, French Jewry has also made a massive and unexpected return to religious observance, creating a new demand for kosher cuisine. According to the Shamash worldwide database, France now boasts 379 kosher restaurants, for a Jewish population of about 500,000. (By contrast, the United States has 5.5 million Jews but only 1510 kosher restaurants). Unfortunately, Nathan’s vision of France and French-Jewish cooking has not caught up with these developments. She scants the vast array of kosher restaurants that have transformed Jewish life in France, bringing French-Jewish food to prominence and raising its standards of quality to unprecedented levels. Her list of eighteen notable restaurants includes only three certified kosher restaurants. A fourth restaurant, which she describes as kosher, claims indeed to be so, but was never certified by any rabbinical authority.

Nathan’s geographical sense of the Jewish Paris scene is similarly outdated. The Marais and Belleville, of which she writes fondly, have largely vanished as Jewish areas. But visitors who stroll around by Rue Manin (near the Buttes Chaumont park), Porte de la Villette (claiming Europe’s largest kosher meat market), or such West End locations as Rue Jouffroy d’Abbans, Boulevard des Ternes, and Place Victor Hugo, will see Jewish eateries of all sorts, as well as bakeries, supermarkets, butchers, and wine merchants.

And what about the chefs? Nathan also includes several characters and recipes that have only a tenuous relation—or no relation at all—to Judaism. Thus, Daniel Rose, a promising young American chef in Paris, is quoted on several occasions. While Jewish by birth, Rose neither observes the Jewish dietary laws nor shows any interest in traditional Jewish dishes. It would have been more to the point to pay a visit to Chef Ghislaine Arabian, an established star in French cuisine. Arabian is not Jewish, but she has advised Sushi West, a kosher Asian fusion food restaurant chain.

These are disappointing lapses but they should not deter the reader. Nathan is sometimes arbitrary or misleading; but she also has a real and even unique talent for spotting culinary masterpieces in unlikely places, uncovering the Jewish genealogies of classic French dishes, and finding the human story behind a piece of cake or a glass of wine.

A few year ago, Israel’s Supreme Court banned the force feeding of geese necessary to produce foie gras. This was, to digress for a moment, a fourfold blunder. Foie gras is extraordinarily nutritious, a profitable export, the result of the goose’s natural propensity to stock fat, and a genuine Jewish culinary tradition adopted from ancient Egypt. Noting the last two of these points, Nathan introduces us to Anne-Juliette Belicha and her husband, Maurice, who enlisted the help of a local butcher and started producing foie gras under rabbinical supervision in Périgord, one of the top gastronomic enclaves of southwestern France, where she was pleasantly surprised by the gentleness of the actual force-feeding (gavage). “I watched this process for more than an hour,” writes Nathan, “and did not hear a quack.”

Another character in Nathan’s story is Shimon Bellhassen, a Talmudist and veterinarian-turned-shepherd with eleven children who produces kosher cheese—twenty different kinds, including Tomme de Savoie and Reblochon—in a little town in the Alps home to one of France’s top yeshivot.

And how can one not be moved by the story of Lionel Barrieu, the grandson of a Catholic police officer who went underground rather than take part in the round-up of Jews during World War II? A convert to Judaism, Lionel—now Ariel—is particularly proud of a kosher version of his favorite dish, meat lasagna, with a milky non-dairy Béchamel sauce.

Equally fascinating are Nathan’s investigations into the ancient Jewish dishes that are found in the diets of both Ashkenazic and Sephardic Jews. Cholent, the classic Ashkenazic bean-and-barley Sabbath stew, is a descendant of chamin, a dish described in Talmudic literature, and a not-so-distant relative of a Sephardic stew called adafina (“buried stew”) in Arabic, or dfina in Judeo-Arabic. But it also turns out that southern France’s trademark cassoulet, a thick stew with white or fava beans, duck, and lamb, is probably a local chamin adopted by Christians in the 14th century when the Jews were banished.

Another interesting case is the wheat soup (Grün Kern in German, or soupe au blé vert in French) that was customarily served on Friday nights by Ashkenazic Jewish families from eastern France. Nathan “asked all over for a recipe” without success, until by chance, she saw a Tunisian from Paris photographing his mother making soup and realized that it was almost exactly the same dish.

Its shortcomings notwithstanding, Nathan has written a book that one might liken to an old kosher Sauternes wine: sweet, immensely rich, and asking to be savored.

Suggested Reading

Moses, Murder, and the Jewish Psyche

Sigmund Freud had always identified with Moses. At the end of his life, as the Nazis rose to power, he returned to the Bible and the origins of the Jewish psyche. We all know his scandalous theory—or do we?

Some Calming Words

Hillel Halkin shouldn’t be so worried. Democracy is still alive and kicking in Israel. The Israelis who didn’t vote like him aren’t stupid. They’re no less wise, humanitarian, and upright…

In the City of Killing

The Kishinev pogrom originated in a rumor, widely disseminated and believed around the area that Easter, that the imperial authorities had given permission for several days of uninterrupted violence against the Jews.

The Shtetl Trap

How should we think about the Eastern European market town? Did the shtetl ever have a golden age?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In