In the City of Killing

When in late May 1903 Prince Sergey Urusov learned he was to be appointed governor of Bessarabia, a province in the far southwest of the Russian empire, on the border with Romania, he knew—or so he wrote later—as little about the region as he did “of New Zealand or even less.” One thing he did know was that there had been anti-Jewish riots there, in the city of Kishinev, the previous month; the governor had been dismissed and Urusov was being sent in to clean up the mess. Around the world, the affair had made headlines and the imperial government was keen to see calm restored.

The basic facts were already well known. On the afternoon of April 19, Easter Sunday, after church services had ended, gangs of youths had begun picking on Jewish homes and shops. Amid shouts of “Kill the Jews!” they had gone on a two-day rampage that ended with 49 people dead, many women raped, hundreds injured, and much destruction of property. The local police failed to intervene, and the bloodletting and violence were only brought to an end when troops finally began to patrol the streets and make arrests.

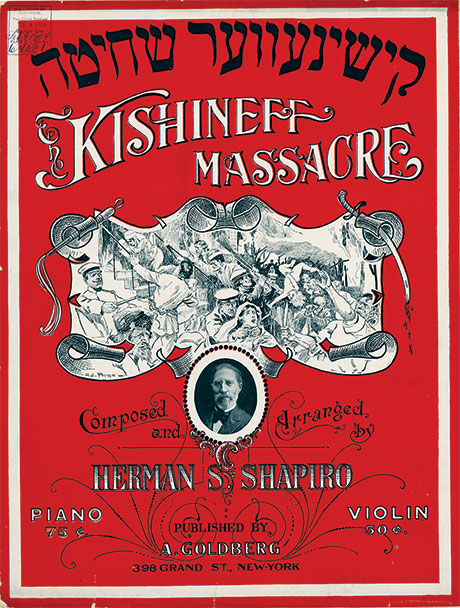

Although there had been a wave of anti-Jewish violence following the assassination of Tsar Alexander II, such an event was still unusual and shocking. Indeed, the casualty toll at Kishinev in one day exceeded the number of dead in the more than 200 pogroms that erupted across the empire in 1881–1882. It was Kishinev that popularized a Russian word—pogrom—and made it common currency in English. When a translation of Urusov’s memoirs was published in America in 1908, the editor helpfully cited a recent entry from Murray’s New English Dictionary: “Pogrom. Devastation. Destruction. An organized massacre in Russia for the destruction or annihilation of any body or class, chiefly applied to those directed against the Jews.”

Organized by whom was the question asked from the start. For some the finger pointed directly to the highest levels of the Russian government, and in particular to the known Judeophobe Minister of Interior Vyacheslav Plehve. The Times (of London) published a leaked letter that appeared to show the minister himself had directed Governor von Raaben, Urusov’s predecessor, not to obstruct the rioters. The Russian ambassador in Washington suggested by way of alternative that the problem was one of class hatred—the peasants were poor, and moneylenders tended to be Jewish—so that what looked like a religious animosity was, in fact, economic in its origin. Nevertheless, the fault—so far as the ambassador and many other Russian conservatives were concerned—lay with the Jews themselves for their purported economic exploitation of the peasants in the countryside. Some Russian anti-Semites even believed the Jews had instigated the pogrom deliberately in order to bring international embarrassment to Russia.

None of these explanations really work. Although Plehve’s animosity against the Jews was well known, the letter was a forgery, almost certainly composed by enemies of his who believed it corresponded to his sentiments. Urusov himself was convinced from the start that, much as he detested Plehve, the cause of the troubles lay elsewhere. Anti-Semitism, whether economic in origin or religious, was clearly a factor, but since it was endemic across the empire, it could hardly explain why the violence erupted when and where it did. Easter had always been a sensitive time, but many Easters had come and gone with no trouble, and this was the first to cause such bloodshed.

The story of the Kishinev pogrom is a useful reminder that fake news, conspiracy theories, and rumor-mongering did not begin with the rise of Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube. Indeed, the era of the pogrom was, as the distinguished historian of Russian Jewry Steven Zipperstein emphasizes, in some ways where all this began. The pogrom itself originated in a rumor, widely disseminated and believed around Kishinev that Easter, that the imperial authorities had given permission for several days of uninterrupted violence against the Jews. Peasants had actually made their way into the town in that belief, though it should be noted that most of the rioters appear to have been townspeople. And many believed another rumor that Jews had ritually murdered a Christian in a nearby town a few days earlier.

The forged Plehve letter helped spread the mistaken view worldwide that the pogrom’s instigators were to be found at the apex of the imperial regime. More significantly, there was another forgery that came to light in those days, carried in the newspaper of one of Kishinev’s most notorious Jew-baiters, Pavel Krushevan, that claimed to reveal the truth about the Jewish bid for world domination: Yes, as Zipperstein shows, drawing upon the research of Italian linguist Cesare De Michelis and others, the first version of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion seems to have sprung directly out of the ideological ferment that followed the 1903 pogrom.

About the 1903 pogrom’s wider significance there can be little doubt. Although Kishinev was soon to be dwarfed by the anti-Jewish violence that erupted amid the revolution in 1905–1906 and again, on an even larger and bloodier scale, in the aftermath of war in 1918–1919, it was a major event in its day and one that became both an abiding stain on the reputation of tsarist Russia and a collective trauma in the modern Jewish consciousness. It is not surprising that the whole tragic story should have attracted Zipperstein’s attention. A professor at Stanford University, whose writings include books on the Jews of Odessa and a biography of Ahad Ha-Am, Zipperstein is ideally suited to explore the history of the Kishinev pogrom. Equally at home in Russian, Hebrew, and Yiddish, he is able to explore the event from all sides. Since the pioneering work of his teacher Hans Rogger and John Klier, there has been a sustained debate among professional historians about the nature of the mass violence that erupted through the pogroms, and Zipperstein’s book is enriched by this discussion and builds upon it.

“On the surface Bessarabia seemed quite beautifully sylvan, a land of rolling hills and pastures full of grazing sheep, wooded in its north, with fewer trees in the south.” Thus begins Zipperstein’s pen portrait of Bessarabia, a former Ottoman province relatively recently incorporated into the empire and a large agrarian society increasingly connected to the global wheat trade, positioned strategically between the granary of Ukraine and the boom port of Odessa. As for the city at the heart of this story: “by the early twentieth century, Kishinev had grown into a prosperous, commercial entrepôt, its vibrancy the product of the region’s agricultural bounty, a lively black market, and a superb mayor who bludgeoned local businessmen to contribute to the city’s improvement.” While always in Odessa’s shadow, Kishinev was growing rapidly, and, as in other cities, it was home to a large and expanding Jewish population. This was itself only part of a larger and immensely polyglot society: Urusov’s waiting room was filled with petitioners speaking 10 languages. Yet despite this heterogeneity—little of which, it must be said, has made its way into the pogrom discussion (which generally presents a world bifurcated into Jews and Orthodox Russians)—Bessarabia did not have a history of unusual ethnic violence and indeed had remained unscathed in the early 1880s. This was a frontier society in which the imperial state was strained to provide effective administration. The grand buildings in the new part of town and fine central boulevard could not hide the poverty down by the river—more like a brook—that trickled through the town.

Where the etiology of the pogrom is concerned, Zipperstein follows in the path forged by Rogger and Klier. Dispensing with the old myth that this had been ordered from above is a key task and easily done. Urusov and others had made it quite clear at the time that the problem did not lie there. Rather, the violence was whipped up by local elites, town boosters like the journalist Pavel Krushevan, who combined work as a Kishinev publicist with intense anti-Semitism that he propagated in his newspapers. Alongside Krushevan was a wealthy contractor in the construction business named Georgi Pronin, a magistrate, a doctor, and a few workers. These activists had used the fake news of the supposed ritual murder in nearby Dubossary and distributed leaflets and circulars in the town’s taverns and cafes, and later passed around weapons such as axes and iron bars, as well—men in the construction business were always valuable from this point of view.

If we return to Urusov, we see other less-tangible factors invoked as well, less dramatic perhaps than the figures of the culpable but equally important in understanding what happened. As an operator within the bureaucracy and a connoisseur of its workings, the governor remains a superb guide to the way Russian rule itself prompted events that caused the regime deep embarrassment. He notes the lack of resources available in the event of a breakdown of public order and the fact that both policemen and local troops were unreliable. The police in particular had a special animosity toward the Jewish population, in part because the special legislation surrounding Jews was almost impossible to enforce and constituted an immense burden on their time. In addition, there was what amounted almost to a local tradition of what Urusov called “Jew-baiting” within the provincial administration that normally expressed itself in demands for money but could, on occasion, emerge as a kind of tolerance for rioters.

But the Russian dimension is not Zipperstein’s sole focus. He is also concerned with tracing the pogrom’s reverberations among the Jews, reverberations which, as he rightly emphasizes, were international in their scope. He shows its enormous impact upon Zionist thought, thanks in no small measure to Ahad Ha-Am’s emissary to the town, the 30-year-old poet Chaim Nachman Bialik, whose extraordinary on-the-spot investigation in the immediate aftermath of the pogrom resulted not only in five notebooks of eyewitness testimonies (in Yiddish) but also in his great Hebrew poem “In the City of Killing,” which Zipperstein describes as “the finest—certainly the most influential—Jewish poem written since medieval times.”

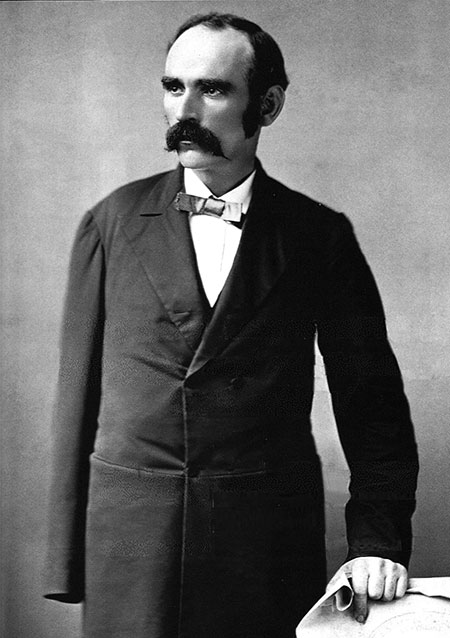

But there were other investigators too whose work left more lasting traces than that of the tsarist police. One was Michael Davitt, a one-armed Irish journalist whose extraordinary life included republican gunrunning, a stint in solitary confinement in Dartmoor, and pro-Boer activism during the war in South Africa before he was sent to Russia by William Randolph Hearst, producing a series of hard-hitting articles on the Kishinev pogrom, along with a revealing diary that Zipperstein also draws upon. Another was the remarkable Anna Strunsky. She was a young Jewish emigrant to the United States from Russia who had become a socialist and travelled back to Russia in the aftermath of the 1905 revolution with her partner, William English Walling. What makes Strunsky and Walling important is less their journalistic work on the plight of the Jews in Russia and more the connections they drew between the pogroms and ethnic violence in the United States. When race riots broke out in Springfield, Illinois in August 1908, the first to target African Americans in the North in half a century, the parallel with what they had seen in Russia immediately occurred to them. One of the outcomes was the formation in their New York apartment, a year later, of the NAACP.

Despite the work Zipperstein has done in the archives, Pogrom is less a new interpretation of Kishinev than a narrative account together with a probing but incomplete analysis of its larger significance. Its achievement is to make connections that have not been made previously or are still too rarely made and to do so in an accessible, sometimes elegant way. There is one inexplicable omission, however, and that is the absence of any real treatment of the pogroms and the Russian left, the Russian Jewish left, and the Bund in particular. Zipperstein writes that “the Bund’s keen preoccupation with the pogrom was silenced by its insistence on its internationalism.” But, in fact, not only did Bundist publications extensively discuss Kishinev, the pogrom contributed to an animated argument about the place of violence in the revolutionary movement, and in short order to the formation of armed self-defense units. As Zipperstein later mentions, these units played an important part in minimizing the bloodshed a few months later when another pogrom erupted in the town of Gomel. If not quite a comprehensive account of Kishinev and its aftermath, then, Pogrom is a wide-ranging survey by a major historian of one of the defining events of modern Jewish history.

Suggested Reading

Hasidic Renewal on the Brink of Destruction

Kalonymus Kalman Shapira, a Hasidic communal leader, and Hillel Zeitlin, a writer who sought to bring Yiddish religious books to a new audience, met on the page, and almost certainly in the Warsaw Ghetto.

Pittsburgh Jews, Squirrel Hill, and the Tree of Life

In the wake of the recent massacre, a local historian tells the story of the Pittsburgh Jewish community and the 154-year-old Tree of Life synagogue.

A Letter to Mama

A story by Isaac Bashevis Singer, with an introduction by David Stromberg.

Jocasta Speaks

The Jewish woman, before feminism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In