The Shtetl Trap

As its somewhat forbidding title indicates, Jeffrey Shandler’s new book focuses not so much on the Eastern European market town as on the changing ways in which Jews have employed it as “social space to think with,” a ready-made idiom with which to address contemporary concerns. Following a brief section titled “Phenomenon,” on the historical shtetl itself, Shandler traces its evolving image through several centuries and regions. Thus, collapsing time and space, Shandler introduces readers to the 19th-century Hasidim, who adopted the names of their towns (i.e., the Belzer, Chortkover, Gerer, and so forth), thereby imbuing them with sanctity and eventually making them “sites of return journeys for [contemporary] hasidim seeking spiritual enhancement.”

By contrast, he argues, maskilim from Yosef Perl to Sholem Yankev Abramovitsh (Mendele Mokher Seforim) transformed the shtetl into a literary abstraction of stultifying provincialism. In their satires, shtetlakh became archetypes with “comical, faux-indigenous names” like Glupsk (in fact, a provincial town, not a shtetl). This is correct as far as it goes, but it fails to note the growing complexity of maskilic attitudes toward the shtetl in the latter part of the 19th century as disillusionment with selective emancipation set in—something one can see, for instance, in the fiction of S.Y. Abramovitsh.

In the 20th century, Shandler shows, among other things, how the shtetl was perceived as a repository of authentic Jewish folk culture on the eve of World War I, as a fossil in Soviet Jewish culture, as a symbolic home for American immigrant members of the landmanshaften groups (a kind of combination of the Eastern European kahal and American fraternal orders), as an object of longing in interwar American Jewish popular culture (as, for instance, in the films of Molly Picon), and as a symbol of loss after the Holocaust. Its increasing remoteness from us now has endowed the shtetl with, Shandler writes, “greater significance as a metonym for a bygone way of life and for its values—intimacy, piety, provinciality, insularity, [and] rootedness.”

Shandler also showcases the creative ways in which a generation with no direct memories of Eastern Europe has conjured up images of the shtetl as a form of bereavement. He correctly cautions, however, that these projects can be both liberating and limiting. Through their participation in Hasidic pilgrimages, heritage tours, and museum visits, Jews have tried to experience the shtetl vicariously, to touch the things, breathe the air, and walk in the footsteps of their ancestors. Such journeys attempt to defy “the destructive will behind the Holocaust,” but they also demonstrate the impossibility of return. Projects such as Yaffa Eliach’s attempt to recreate a shtetl on 67 acres in Rishon Lezion, Israel, only accentuate the chasm between the original and the reproduction. Such expressions of reflective nostalgia sometimes acknowledge their contradictions but, to quote, Svetlana Boym, always “cherish the shattered fragments of memory.”

According to Shandler, 20th-century scholarship on the shtetl, which appeared much later than artistic representations, was always driven by activist agendas. Folklorists like S. An-sky (Shloyme Zanvyl Rapoport) traveled to shtetlakh to gather the raw materials of Jewish folklore that would inform “projects of political action and cultural innovation.” Similar motivations lay behind the creation of YIVO in 1925. The author demonstrates how post-Holocaust works such as Abraham Joshua Heschel’s The Earth Is the Lord’s: The Inner World of the Jew in Eastern Europe and Mark Zborowski and Elizabeth Herzog’s extraordinarily influential Life Is With People constructed an enduring paradigm of an exclusively Jewish world enveloped in sanctity. Historian Lucy Dawidowicz’s anthology, The Golden Tradition: Jewish Life and Thought in Eastern Europe, was an important corrective, shifting the focus from the evocation of a timeless ethos back to figures who actually lived in history. Nonetheless, the idea of “the shtetl,” as “a social space to think with” (to return to Shandler’s useful formulation)—that is, as a paradigm—has persisted.

Shandler writes that even today’s researchers have found it difficult to leave behind “devotional or communally affirmative motives” for their work. One might add that even a sophisticated, erudite study such as Shandler’s sometimes appears insufficiently removed from the cultural processes of memory and imagination that it documents. The tendency to use the shtetl as a paradigm is a trap that keeps us from seeing, even at a historical distance, actual shtetlakh and the people who lived in them.

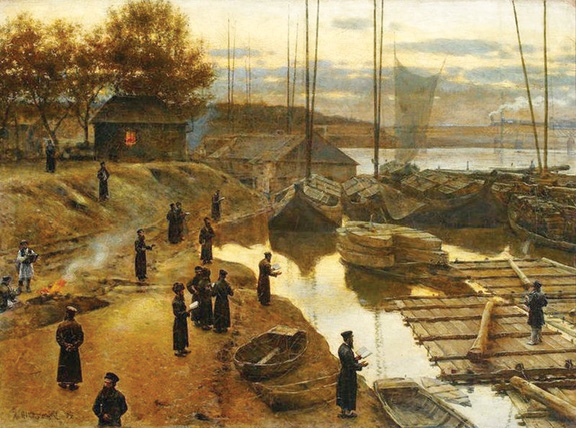

In contrast to Shandler’s discursive shtetl, Yohanan Petrovsky-Shtern’s town is exceedingly corporeal (if, in the shtetl, life was “with people,” he focuses on a decidedly different class of company than previous chroniclers). On the basis of extensive work in the archives, Petrovsky-Shtern proposes to radically revise the history of the shtetl. He argues that Jews enjoyed a “golden age” in the shtetl from the 1790s to 1840s:

We begin the story of the shtetl’s golden age at the moment when Russia moved westward and inherited these formerly Polish territories with about one million Jews, one third of whom lived in central Ukraine. For the author, this story also began with a hunt for primary sources. That hunt brought me to the strongholds of previously classified archives, where a wealth of documents has lain dormant for more than two hundred years. To gain access to these documents, I sometimes disguised myself as a Ukrainian clerk, a Soviet speleologist, and a Polar explorer. This unorthodox approach yielded several thousand archival sources in seven languages, from six countries and dozens of depositories that reveal the shtetl in its years of glory.

This gives a good sense of the exuberance of Petrovsky-Shtern’s authorial voice. What of his historical thesis? This period is generally associated with the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) followed by decades of reaction and repression, so it is certainly a bold one.

The center of the shtetl’s “years of glory,” Petrovsky-Shtern argues, “revolved around [the shtetl’s] economic axis . . . above all, on the market and money,” which was tied to the fortunes of the Polish landlords. Relying on the scholarship of Gershon Hundert, Moshe Rosman, and Adam Teller, Petrovsky-Shtern affirms that the economic alliance between Jews and Polish magnates in the early modern period propelled a burgeoning Jewish economy, especially in the sophisticated leaseholding (arenda) system. But he doesn’t agree (or even engage) with these scholars’ conclusion that signs of disintegration were already discernable in the Jewish economy by the last decades of the 18th century. According to Hundert, for instance, the erosion of the Jewish economy not only stemmed from opposition from the Sejm (the lower house of the Polish parliament) and the Catholic Church. There were also structural pressures: Jews found themselves at odds with Polish magnates who sought to “rationalize the administration of their [inefficient] estates”—a process accelerated by the Polish partitions.

Not so, contends Petrovsky-Shtern: The partitions suddenly removed all these pressures, leaving “Jews to their own devices,” no longer under Polish control yet not entirely governed by an inept and corrupt Russian provincial administration. Taking advantage of this “lawless freedom,” Jews and Slavs in the Ukrainian provinces profited from the black market economy, which flourished as a kind of Wild West frontier phenomenon. Petrovsky-Shtern’s golden age met its demise when the imperial state finally decided to crack down on these unruly border towns out of “xenophobia and nationalism.” As a result, he writes, the shtetl disintegrated into a “ramshackle town, perhaps even a village, stricken by poverty and pogroms.”

Despite Petrovsky-Shtern’s bold thesis about the non-interference of the Russian state in shtetl affairs until the 1840s, he begins his story with the meddling policies of Catherine II. In the 1790s, he argues, the Empress’ desire to suppress the subversive Poles led to the establishment of new customhouses, excise taxes, and bans on luxury goods. Such measures, quips the author, posed few obstacles for Jewish borderland traders: They simply resorted to creative solutions including smuggling contraband, paying bribes to corrupt officials, and forming “gangs” with rough non-Jews, even Cossacks who, he notes, are “notoriously present in Jewish cultural memory as cold-blooded killers of Jews.” These contrabandists may have been “nightmares for Russian administrators,” but Petrovsky-Shtern proudly declares that they were “fighters for freedom for ordinary Jews and Slavs.” It was this “Judeo-Slavic brotherhood,” united against two common enemies—informers and capricious Russian bureaucrats—that formed the basis for the “golden age.”

The contraband cases are riveting; however, like many court cases, they involve criminals who were caught and prosecuted. Without a more rigorous comparison with law-abiding merchants, it is difficult to judge whether they represent the norm or, as Rabbi Isaac Mikhal of Radzivilov put it, the misdeeds of a few members “from the rabble who invent ways to bring contraband into Russia through their swindling.” Whatever the case, if economic restrictions (during a period of supposed “lawless freedom”) really turned respectable merchants into “a mafia of Jewish contrabandists,” how golden was this age? Moreover, the existence of black markets generally signals economic decline and stagnation, not growth.

According to Petrovsky-Shtern’s golden age model, the Jewish liquor trade and tavern culture were also central to shtetl life. Employing excise tax records, he documents the prominent role of Jews in this lucrative business. The tavern, he writes, provided a space in which to discuss business, engage in matchmaking, gossip with Russian officers and Polish gentry, and, of course, drink. It also allegedly played a mystical role in Hasidism: The rebbes “claimed that the tavern could bring them closer to God.” While alcohol no doubt played an integral part in Hasidic social life, this borders on the19th-century parodies of the maskilim.

The social ills of drunkenness and alcoholism that plagued Jewish families who complained to rabbinic authorities such as Rabbi Eliyahu Guttmacher (1796–1874) also find no place in Petrovsky-Shtern’s valorizing account of the tavern. He maintains, in short, that drinking was not only a good thing in the golden age but entirely compatible with economic production. The good times would have continued had the Russian state not intervened to undermine the Polish town owners by removing “one of their main sources of income—the Jewish tavernkeeper.”

Lovers of the rowdy tavern and skillful contrabandists, Jewish residents of the golden age shtetl were, Petrovsky-Shtern writes, “quite the opposite of those meek, short, narrow-shouldered, nearsighted, hunched over, and physically inept images we find in memoirs and travelogues and prose narratives.” Rather, they were robust men who could “handle weaponry” and deliver “horrible obscenities . . . that could knock a police man off his feet.” Zionist historians were wrong; Jews mastered the language of violence “before they discovered Pushkin and Gogol,” which put them on “an equal footing with Christians long before any civil rights did.” For the objects of this violence, this age of criminality could not have been all that golden, but their experiences barely register here.

Not only could Jews fight for themselves; the author observes, based on police records, that they also resembled their Slavic neighbors in physical appearance: “fair-haired and shaven or bearded yet almost always without sidelocks or large, hooked noses.” Perhaps, he suggests, Jews owed their Slavic appearances in the reports to the limited vocabulary of the police clerks or the absence of late 19th-century anti-Semitic discourses imported from Western Europe. But part of what made it a golden age, the author suggests, is that even the police described Jews “as genuine Slavs,” a sign of Ukrainian interethnic harmony.

If Petrovsky-Shtern’s archival research offers us fresh materials on economic matters—albeit framed with dubious generalizations—his treatment of family and women moves us decidedly backwards. In fact, notwithstanding his anti-sentimentalist stance, his own subtitles strike a nostalgic note: “Beautifying a Housewife,” “Holy Sex” (with a nod to Shmuley Boteach, no less), “Protecting the Family,” and so forth. His treatment of these topics is shockingly crude and simplistic, reminiscent, again, of 19th-century maskilic satire. He writes that the matriarchs ruled the roost while their burly husbands only imagined that they had power. Many Jewish wives—“if not most . . . resembled Toibe Sosye from Mendele’s autobiographical novel—a corpulent woman with a shrieking voice.” Even if every woman in the shtetl actually weighed four hundred pounds and had a voice like a belfry, what would that prove about the family?

And what can one say of the following in an ostensibly serious work of history that invokes Clifford Geertz’s ideal of thick description and yet describes marital relations as follows?

To emphasize that family really matters, Yiddish proverbs reinforce the importance of figuring out the sexual urges of one’s wife and meeting them half way, especially those of a young wife, who in Yiddish is described as a devotee of

di groyse kishke—which in this case does not refer to the traditional Sabbath meal.

It is hard to know what is worse here: the brazen generalization or the winking innuendo that accompanies it.

Petrovsky-Shtern also contends that silence was the “best variant of self-defense” against rape for women “chose to preserve family over justice.” They had to depend on the community to resort to “mob violence” or take the offender to a rabbinical court. Perhaps a more informed discussion of how 19th-century societies dealt with rape would have been instructive in explaining women’s silence and shame.

As a result of modernity, the author declares the number of “Jewish illegitimate children and vagabond orphans skyrocketed, and promiscuity became a cultural norm.” Regrettably, he fails to muster any sources to document this trajectory from “holy sex” to widespread promiscuity. More important, the very cases of wife beating, marital rape, divorces, and agunot that Petrovsky-Shtern utilizes to demonstrate the heroic efforts of the community to preserve the sanctity of the family actually suggest serious problems, not a golden age.

The golden age thesis also flounders in his discussion of print culture, which allegedly flourished under the radar of the Russian state until the 1830s. The author claims that independent Jewish printing presses were not only ubiquitous but also published a disproportionate number of Hasidic and kabbalistic books (though most were, in fact, reprints). In 1836, the Russian state took a greater interest in the “harmful content” of Jewish books, closed most of the Jewish presses (except in Zhitomir and Vilna), and imposed stricter censorship. This is all well known, but according to Petrovsky-Shtern “reading a censored kabbalistic or Hasidic book persecuted by the regime became for Jews what touching the Turin Shroud or kissing a healing icon was for a devoted Christian.” Concrete documentation would have been helpful in appreciating such an intriguing comparison.

The demise of the golden age shtetl, contends Petrovsky-Shtern, was a byproduct of the czarist regime’s conquest of the western borderlands and suppression of Polish economic, political, social, and cultural institutions. Just as the state’s negligence had created the conditions for flourishing shtetlakh, “state-supported xenophobia” suffocated them by “debilitating their markets and weakening trade networks” and forcibly supporting administrative towns like Zhitomir. In fact, however, cities represented an expansion of the local economy, not its contraction. What really “brought down” the shtetlakh was the railroad, not the establishment of Russian provincial centers. Moreover, the real threat of Polish nationalism was in the northwestern provinces of Lithuania, not in the shtetlakh of southern Ukraine, as demonstrated in the Polish Uprisings of 1863–1864.

Equally problematic is the author’s argument that as Jewish merchants migrated to new centers like Odessa, the vibrant shtetl became “an impoverished godforsaken village,” rife with “provincialism, timidity and stupidity, ghettoization, uncivilized manners, a coarse accent, pedestrian thoughts, and bad taste.” Such a theory gives far too much credit to the czarist regime, which could barely enforce its laws of registration among the Jews in the early 19th century, let alone engineer this feat of cultural transformation. Petrovsky-Shtern also reads literary satires of the shtetl as if it were straightforward reportage. Rather than going “beyond colloquial stereotypes” of the sentimental shtetl, The Golden Age Shtetl more or less reverses them: brawny Jews, vibrant black markets, Slavic-Jewish interethnic harmony, the impious tavern as the center of social life, sexually starved corpulent women, and so forth.

The dizzying wealth of archival sources drawn upon in this book is impressive, but often enough they undermine the credibility of the historical portrait Petrovsky-Shtern wishes to paint. (In other instances, the details from these unpublished sources are simply incongruous—we are given little background, for instance, on an amazing and rare count of Rabbi Abraham Twersky’s “447 books,” incongruously noted in a policeman’s report about criminal schemes against the “Sovereign Emperor.”)

In analyzing the fascinating case of Gershko Kapeliushnik, the hat maker, Petrovsky-Shtern seems to me to take too much liberty with his sources. The Christian apprentices accused him of uttering words that were “tempting and blasphemous for Christians.” Petrovsky-Shtern claims that the apprentices’ reluctance to provide details “implies that Gershko enticed them with common Judaic invectives against Christian theology: Jesus was a poor bastard and the immaculate conception was obstetrical nonsense.” If “bastard discourse” were so common in this time and place, one would expect other similar cases to be adduced as well.

Despite Petrovsky-Shtern’s rich base of archival sources, he does not show that a golden age of the shtetl ever existed. He is also not the first to depict a rough-and-tumble shtetl. Consider Sholem Asch’s fictional shtetl “Koyl,” where Reb Israel Szochlin and his rugged sons, “who were no students,” resided, surrounded by their Jewish-Slav gang, their livestock, and many taverns. Though the inhabitants of the shtetl felt thoroughly ashamed of these coarse boors, butchers, and fishmongers, “if a shepherd set his dog on them, or a drunken Gentile started beating Jews—everyone, old and young ran screaming into the [Koyler] Street.” Even this new history, based on archival sources from the former Soviet Union, falls into the trap of painting yet another paradigmatic shtetl in broad strokes and garish colors.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Funny How a Poem Can Get Under Your Skin

On Celia Dropkin’s avant-garde Yiddish break-up poem and a political insight.

The Man’s Learning Moves Me

Isaac Casaubon, the Hellenist who loved Hebrew.

Adventure Story

Anita Shapira's new book raises the bar for short histories of Israel.

In Whose Image?

On the spectrum between animal and divine, where do human beings fall?

hurwitzedith

aT bOOKLYN cOLLEGE i DID A RESEARCH PAPER ON tHE sHETLE AND THE KIBBUTZ AND HOW SIMILAR THEY WERE. i ONLY HAD zABOWSKI AND hERZOG IN THE FIFTIES. hOW ENLIGHTENING IT IS TO REVIEW ALL THE DOCUMENTATION THAT "pETROVSKYsHETERN,S BOOK PROVIDES"iTS EQUALLY IMPORTANT TO HAVE THE OVERALL VIEW OF sCHALER'S FINE SYNTHSIS TO COMPLMENT IT.

charles.hoffman

after years living in the US, my father reflected on the shtetl where he'd been raised:

"It was a one-horse town; 'til somebody ate the horse"

Looking back on poverty and deprivation with nostalgia is the sign of a life with no hope in its future.

efrayim

This golden age book sounds most odd

Marcus Moseley

The Shandler book yeh--that is the academic discourse of the day--innocuous.

The "Golden Age" book I agree with the reviewer is more than a little bit disturbed and disturbing.