Minyan 2.0

In 1953, Abraham Joshua Heschel delivered an impassioned address to the annual convention of Conservative rabbis, asking: “Who knows how to pray, how to inspire others to pray? . . . Who knows how to kindle a spark in the darkness of the soul? . . . People take their precious time off to attend services. Some even arrive with profound expectations. But what do they get? . . . Sometimes even the rabbi sits in his chair wondering: ‘Why did all these people flock together?'”

Between the year 2000 and the present, over sixty separate independent minyanim (prayer communities) have sprung up in the United States and Israel, providing a means for young Jews disaffected from large synagogues to flock together. These minyanim are, in some ways, descendants of the “havurot” (fellowships) of the 1960s and ‘70s for which the Jewish Catalog served as a guide. Those participatory communities were marked by a countercultural, anti-institutional, Do-It-Yourself aesthetic, of which the new minyanim, to some extent, partake.

Of course, Orthodoxy has always had minyanim; shtiblekh and other lay-led prayer groups are the historical norm, and maximum-capacity suburban synagogues the American anomaly. As with the members of havurot, many members of my generation of under-30 Jews say they feel excluded from religious life. Justifiably so: the suburban mausoleum that is the liberal synagogue was, at best, built for a sociological reality decades out of date. A friend of mine reports that when she goes to the synagogue of her childhood, “No one can remember if I’m in college or grad school, if I’m me or my sister—and everyone is either 15 years older or 15 years younger than me.”

In Empowered Judaism, Elie Kaunfer defines an independent minyan as a prayer community that has been organized and led by volunteers, has no paid clergy or denominational affiliation, and meets at least once a month. It is important to distinguish further between two types of independent minyan, which, while often possessing overlapping sets of congregants, have very different motivating impulses. First, there are “partnership minyanim” like Minyan Tehillah of Cambridge, Massachusetts; Darkhei Noam of New York City; and Minyan Urim of New Haven, Connecticut. Fundamentally a response to the difficult question of women’s roles in the Orthodox world, they rely on a controversial halakhic responsum of Rabbi Mendel Shapiro allowing women to lead non-obligatory parts of the prayer service. (Elitzur and Michal Bar-Asher Siegal’s online “Guide for the ‘Halachic Minyan'” is a good resource for such communities.)

The second type of minyan is not an outgrowth of halakhic re-interpretations within Orthodoxy or a response to segregated gender roles, but an effort to meet a “crisis in spirituality,” the crisis that Heschel had already articulated to the Conservative rabbis assembled in 1953. These minyanim, such as Harlem’s Techiyah and Washington, D.C.’s Tikkun Leil Shabbat, presuppose the permanence of innovations made by the Reform and Conservative movements in having women lead all parts of services, men and women sit together, and both count in the prayer quorum. Instead, their aim is to provide an egalitarian prayer service, usually with the full liturgy, but with feeling.

Kaunfer’s Kehilat Hadar is a minyan of the second type, one that has expanded into a non-profit institute (Mechon Hadar) and a yeshiva (Yeshivat Hadar). His Empowered Judaism argues that the reforms introduced by Hadar, and the independent-minyan movement more broadly, can transform Jewish life across, and around, the denominations. And his book arrives on a raft of praise. Hosts of rabbis and Jewish leaders laud it as “remarkable,” “incisive,” “inspiring,” “a passionate and brilliant manifesto,” “a call to revolution,” “a ‘must read,'” “essential reading,” “a prophecy of hope and new vision,” and a “testimony to the vitality of Jewish life.”

Kaunfer introduces the book by telling about his own youthful experience. The son of a Conservative rabbi, he attended a Conservative day school, was active in Harvard Hillel, had a challenging relationship with a religiously skeptical girlfriend, worked as an investment banker, spent time in Israel, started a minyan in New York, became a rabbi, and married a woman he met at the minyan he founded. Proceeding from this bit of autobiography, Kaunfer then narrates the story of the creation of Kehilat Hadar, his “model of empowered Judaism.”

“If you could design your own prayer community from scratch, what would it look like?” In 2001, Kaunfer sat down with two friends on New York’s Upper West Side and drafted a template: “a fully traditional liturgy and Torah reading; a commitment to full gender egalitarianism; a short (five-minute) dvar Torah [piece of homiletics]; a lay-led ethos with high standards of excellence; a service that doesn’t drag and engages the daveners [worshippers] through music.” He goes on to explore the movement, devoting a chapter to various minyan leaders talking about a particular aspect of their institutional lives: children’s services (DC Minyan); membership (Brookline’s Washington Square Minyan); community (Jerusalem’s Shira Hadasha); environmentalism (Washington, D.C.’s Tikkun Leil Shabbat). The book ends with a chapter on “how empowered Jews pray” and, finally, a disquisition on “the real crisis in American Judaism”—for Kaunfer, not the red herring of assimilation and intermarriage, but the “crisis of meaning.”

Questions of meaning, however, are difficult terrain for any author to navigate. As Heschel asked: “Who knows how to kindle a spark in the darkness of the soul?” So perhaps one shouldn’t be surprised that in Empowered Judaism, Kaunfer is mostly concerned with brass-tack suggestions for facilitating prayer and community: keep divrei Torah short; set up seating in rows instead of in a circle, to safeguard prayer from the feeling of being watched; send out announcements of forthcoming events via e-mail instead of spending live time reading them aloud at services; start a collection of crocheted or suede yarmulkes for newcomers, so they aren’t stuck in the “outsider garb” of souvenir bar-mitzvah kippot and scarf tallitot.

All sensible ideas, even wise, but nothing to nail to the door of Wittenberg. As Kaunfer himself writes: “instead of focusing on new ideas, the Jewish community would be better served by connecting to the original ‘big ideas’ of our heritage: Torah, avodah [worship], and gemilut hasadim [charitable deeds] . . . There is no new ‘big idea’; there is just investment in the old, but in a serious, meaningful, and thoughtful way.”

Part how-to and part paean, the packaging of Empowered Judaism inevitably subverts the product. Kaunfer’s investment in the old gives way to the serious, meaningful, and thoughtful ambitions that he shares with his committed, engaged, intelligent, humble, devoted peers and their vibrant, energized, prayerful, sensitive, passionate, affirming communities.

Kaunfer dispenses much professional-sounding lore about building community by, for example, naming minyan councils “teams” rather than “committees” (“After all, no one likes committee meetings, but everyone wants to be part of the team!”) and cultivating a “culture of appreciation” whereby those who arrive early for shul are greeted with “Good Shabbos. My name is Elie. Welcome! Would you like an aliyah this morning?” This is certainly better than “Good Shabbos, you’re in my seat,” or the brusque sizing-up of “kohen or levi?” Nonetheless, here and elsewhere in Empowered Judaism, one hears the tones of a corporate memo. The hands may be the hands of chaverim, but the voice is the voice of the e-bankers, lawyers, and bright-eyed young professionals who form a core segment of the minyan: stockbrokers in Birkenstocks. As the anthropologist Riv-Ellen Prell has written, “corporate terms like ‘quality control'” as applied to prayer “would have horrified” the egalitarians who created the havurot of the ‘60s and ‘70s.

There is an open secret about Hadar: like many other minyanim, it is funded by lots of organized community money, offered by institutions eager to keep young Jews connected to their heritage. (This may explain why Kaunfer writes like someone who has devoted a big chunk of his life to writing grant applications.) Through this, Jewish organizations, while creating opportunities for young Jews to worship and study—and they do create these opportunities, and these opportunities are valuable—also prop up a not-very-impressive aspect of elite American culture: the long-extended enabled adolescence. In an interview with Tablet, Kaunfer called this period the slacker-sounding “post-college, pre-whatever.” It has also been described by Jeffrey Arnett, a psychology professor, as “emerging adulthood,” and in David Brooks’ more august term as “the odyssey years.”

On the ground, what this looks like is upper middle class Americans spending the ten to fifteen years after college messing around and “figuring out their lives” while postponing marriage, children, and responsibilities. One way or another, the bill for this eclectic adventurousness is footed by parents, or, for the best and brightest, by various institutions and sinecures. Certainly, in opting out of synagogue life, most young Jews become unaccustomed to supporting Jewish institutions financially. (“We can feel connected to a particular religious community without attending, paying money, or even living in the city where the community is located” is Kaunfer’s explication of a survey result showing minyan-goers reporting an average of five different community affiliations.) One should naturally allow for the loops and lapses of individual human lives, but what proponents of this experimental period see as an odyssey is often just a layover in the land of the lotus-eaters. In a faith that initiates its 12- and 13-year-olds into adult responsibility, the concept of thirty-year-olds as “emerging adults” should be, at the least, suspicious.

After their minyan had been meeting for five months, Kaunfer and his co-founders, Ethan Tucker and Mara Benjamin, named it Kehilat Hadar, citing as one reason for the name the Talmudic explication of the etrog as pri etz hadar, fruit of the beautiful tree, or beautiful fruit of the tree—that is, a tree on which “well-ripened fruit from years past coexist[s] with newly budding fruit from the current year.” They go on:

We see this as a metaphor for an ideal internal relationship: we all bring to the community our ripened fruit, the experiences and ideas we have developed in our lives, the patterns and rhythms that define us. The challenge is to be open to new ideas and experiences (budding fruit) without rejecting the ripened fruit of our past. We hope to make our prayer community a space where people strive for that internal integration.

Now that independent minyanim have been through several crop cycles, it is reasonable to speculate about their future. “When people ask what will happen to the minyan as it ages, my experience suggests that it simply won’t [age],” writes Kaunfer. “Most people past their mid-thirties leave the urban area, and a new crop of college graduates moves in . . . The institution itself is actually quite stable, because it caters to a demographic that is constantly replenishing itself.”

This vision of a Shaker-like revolving-door community might be fine if it were true, but is it? As a generation grows up in the minyan, some who get married and have kids will move out of the community—but some won’t. Pretty soon, those who stay will need Hebrew school, they will need bar/bat mitzvah training, and before you can say egalitarianism, bang, they’re a shul. Hadar already has an affiliated nonprofit institute and a yeshiva (“one of the oldest forms of Jewish empowerment education”). The Havurah movement had a necessarily different relationship to institutions (part of their function, in the early years, was to earn 4D draft exemptions for those participants who were studying for ordination), but even they could not resist the institutional pull: in 1979, the National Havurah Committee was founded.

Without a doubt, core minyan-goers have a more serious commitment to community and to prayer than does the average synagogue member, who can rely on institutional staff to look after logistics and lead prayers. There are, however, ragged edges to these commitments. Most minyanim that stress prayer over other forms of Jewish communal life do not meet weekly (Hadar is now an exception). To one parent of a minyan-goer, this signals the unseriousness and “lack of commitment of a generation—they can’t even commit to coming to shul every week.” Steven M. Cohen finds, in “Highly Engaged Young American Jews: Contrasts in Generational Ethos” (published in 2010), that while Jews under forty are animated by “Jewish purpose”—creating minyanim and study opportunities, involving themselves in cultural and social-justice endeavors—they resist what they view as “coercive expectations”: that is, such “once widely accepted normative standards . . . as in-marriage and support of Israel.” To cite one statistic from the Spiritual Communities Study (2007), conducted by the S3K Synagogue Studies Institute in collaboration with Mechon Hadar: 58 percent of minyan-goers have had a romance with a non-Jew, 24 percent in the past year. Kaunfer stops short of endorsing the practice, but he does call this “integration with the non-Jewish world” an indication of the open-mindedness and cosmopolitanism of young minyan-goers. To those who think of these young Jews as the most committed of their generation, such numbers may indicate something altogether different.

In what is perhaps the most disturbing result of this antiauthoritarian impulse, independent minyanim have encouraged the growth of communities without rabbis, and sometimes without anyone above the threshold of don’t-trust-anyone-over x (adjusted for my generation’s protracted youth). Ironically, the word “hadar” is used in Leviticus (19:32) as an injunction: Ve-hadarta p’nei zaken (“Show respect for the elderly”). The tradition is full of instructions to align oneself with a rabbi, a mentor, a sage from the previous generation. On a more practical level, what does it mean, in an age of rabbinic unemployment, to value rabbis as teachers but not as poskim (halakhic jurists), spiritual guides, communal leaders, mentors, or models of integrated Torah learning?

It is true that independent minyanim have not dispensed with one particular role of the traditional rabbi: that of teacher (also the least well-remunerated role, it should be said). Hadar in particular was wise to realize that any prayer group will stagnate if not accompanied by a serious educational component. Judaism is a text-based tradition, and the texts—in different languages, ancient, legalistic—are not easy to understand. But here, too, Hadar is an exception.

Where, finally, do the minyanim stand in the rough spectrum of practicing American Judaism? The preference for Hebrew prayer and traditional liturgy is one indicator, and likely stems as much from the upbringing of most minyan-goers as it does from first principles. In maintaining the traditional Hebrew liturgy, Hadar and other communities are to be praised for appealing to the Orthodox, which the havurot never managed to do. Certainly the right wing of Hadar is left-wing Orthodox in observance. But still: Kaunfer is a dyed-in-the-wool, Cradle Conservative Jew, as are 46 percent of all independent-minyan-goers. It is no accident that of the three leaders of Yeshivat Hadar, both Kaunfer and Ethan Tucker are the sons of prominent Conservative rabbis, and Shai Held is the son of a late professor at the (Conservative) Jewish Theological Seminary.

Although none of them owes the Conservative movement lifelong fealty, Kaunfer’s posture of disaffiliation from nothing-in-particular does feel disingenuous. As Riv-Ellen Prell writes, “no one has fully explained why the Conservative movement has been so successful at socializing Jews who are interested in alternatives to the Conservative synagogue and advocates of transdenominationalism.” The 2007 study found that minyan participants are “groomed, not bloomed Jews.” Their renegade independence from the denominational label has been made possible by years of communal education, involvement, and training in denominational institutions, training for which the Conservative movement as a movement has reaped little reward.

If the independent-minyan movement is, at heart, a Conservative critique of Conservative synagogue life, does it not follow that the phenomenon is much less expansive, and less important, than is claimed? Furthermore, the innovations of independent minyanim are fully compatible with Conservative Judaism itself. Unlike the case of partnership minyanim, whose halakhic interpretations, when introduced institutionally, have led to discord within the Orthodox world, Conservative synagogues would like nothing more than to welcome independent minyanim, and their young members, into the fold. But the minyan movement has taken on a life of its own, abandoning rather than revitalizing the Conservative world.

But that is to suggest that the minyan movement also replicates certain core characteristics of Conservative (and Reform) Judaism, characteristics that, for many Jews-young, old, and in-between-are deeply troublesome in themselves. Here is Kaunfer:

Questions like “Can you play musical instruments on Shabbat?” do not have a simple yes-or-no answer. Rather, the values you might assign to either outcome (“music enhances Shabbat” or “loud music is detrimental to Shabbat”) find expression in the halakhic literature.

Such a non-normative concept of halakha is empowering mostly in the sense that it empowers people to think that they are keeping halakha whether or not they really are. The regnant ethos of our time is taken for Torah.

Heschel was himself in his 40’s—just a few years older than Kaunfer—when he articulated the problem of prayer and the crisis of Jewish meaning to the leaders of the Conservative rabbinate. Kaunfer may think he has solved the problem, but really he has just re-articulated it.

Suggested Reading

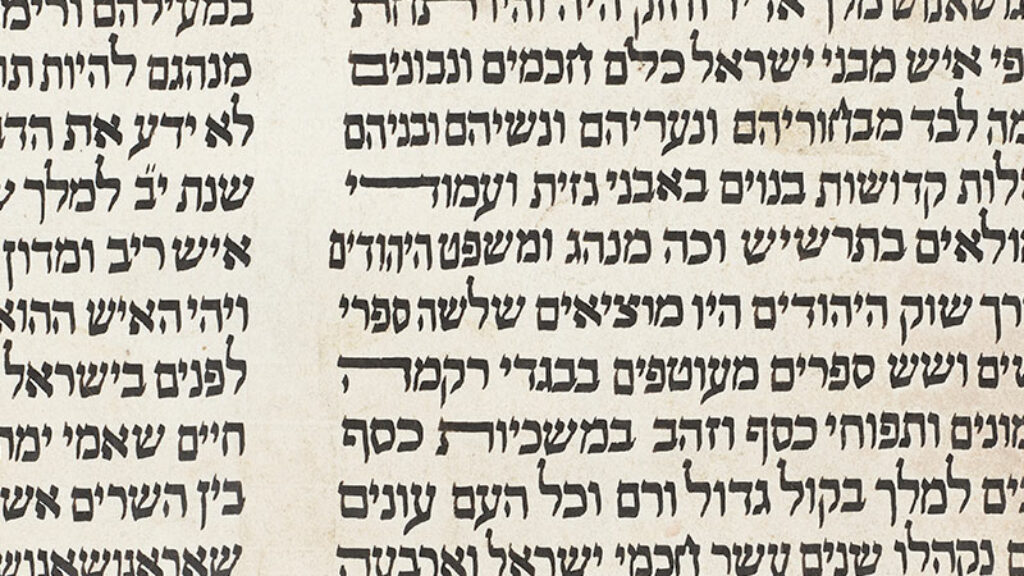

Empty Torah Cases and “Little Purims”

There are more than a hundred known examples of Little Purims commemorating miraculous deliverances of Jewish communities in Europe, North Africa, and the Middle East.

Weird Big Brother

Jacob Frank and his bizarre religious movement still casts a strange spell over. Is Nobel Prize winner Olga Tokarczuk’s newly translated novel the War and Peace of Jewish-Polish heresy?

Rocketmen

A brilliant and moving exhibit at the Israel Museum pairs the Israeli astronaut Ilan Ramon, who died in the space shuttle Columbia explosion, with the obscure biblical gure Enoch, who was also an astronaut of sorts.

Method to Our Madness: A Response to Hillel Halkin

Hillel Halkin is the reason I moved to Israel. I read his Letters to an American Jewish Friend at sixteen, and my life trajectory was changed forever—mine and that of…

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In