Rocketmen

Earth time 5763

20.1.2003

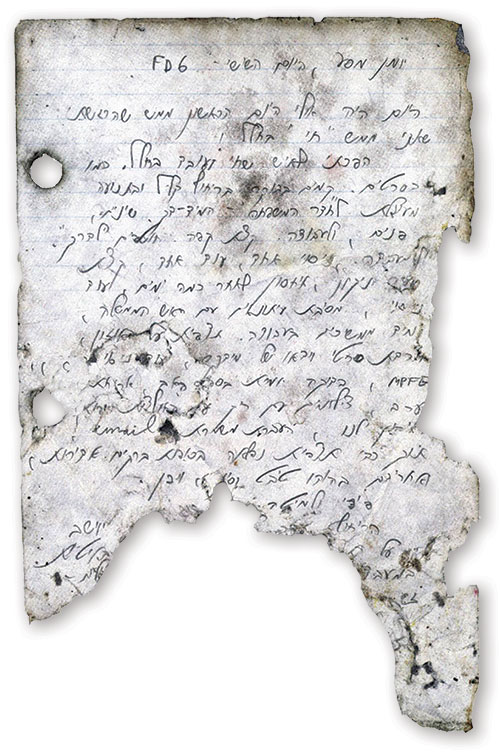

This is not the beginning of a forgotten stanza from Zager and Evans’s old one-hit wonder “In the Year 2525,” but an actual dateline from the extraordinary object at the center of the Israel Museum exhibit Through Time and Space: The Diary of Astronaut Ilan Ramon and a Scroll from the Dead Sea. The entry in question, recorded in a NASA-issued notebook by Israel’s first astronaut, logs the following lines in crisp Hebrew:

Exactly 21 years ago I was meant

to be in space . . . but not my body—just my soul . . .

A mid-air collision.

So here I am, both my soul and my body!

Ramon is referring to a near-fatal crash that took place during his precosmonautical career, when he was a star in the Israeli Air Force (he had been the youngest pilot to participate in the successful Israeli strike on the Osirak nuclear site in Iraq). The collision that took place in January 1982 could have been fatal, wrenching Ramon’s soul from his body and catapulting it into the great void, but he managed to eject and survive. Some two decades later, he flew to outer space as a mission specialist on the space shuttle Columbia. Tragically, just 17 days after its launch, the Columbia disintegrated upon reentry to the Earth’s atmosphere, killing all seven crew members, incinerating the spaceship, and scattering approximately 85,000 pieces of debris, including the damaged pages of Ramon’s diary, over Texas and Louisiana.

One of the themes explored in the small Israel Museum exhibit (it occupies a single, appropriately outer-space-black room) is the drama and pathos that characterized Ilan Ramon’s very 20th-century Jewish life and its place in Jewish history. Born Ilan Wolferman in 1954, Ramon grew up in the Israeli desert town of Beersheva and, like an old-school Zionist, Hebraicized his last name when he became an Israeli Air Force pilot. He conceived of his space mission in national epic terms. On the Columbia mission’s official flight insignia, only Ramon’s name is decorated with a national flag: the Israeli blue star and stripes. As a child of an Auschwitz survivor, Ramon took with him a number of objects linked to the Holocaust, including a haunting lunar view of Earth sketched in the Theresienstadt Ghetto by a 14-year-old boy named Peter Ginz. (Ginz was later murdered by the Nazis, and, in one of the eerie concurrences highlighted by the Israel Museum’s curators, the Columbia was lost on what would have been Ginz’s 75th birthday.) Also packed aboard the spaceship was a miniature Torah that was loaned by Professor Joachim Yosef, a geophysicist at Tel Aviv University who, as a bar mitzvah boy in the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp, had read from the smuggled scroll and kept it safe until liberation.

Some of the pages of the diary, which were not displayed in the exhibit, consist of notes from a press conference given from space, during which Ramon highlighted the historical significance of his mission and drew out the stories of the special objects he brought on board. Other pages, also not displayed, record traditional Jewish prayers and blessings, like the Friday night Kiddush, which Ramon had written out so that he could celebrate the onset of Shabbat—Houston time.

Even after the Columbia disaster, calamity and courageousness continued to characterize the Ramon family’s life. The eldest child, Asaf, was killed in a flying accident not long after graduating from Israeli Air Force training. Ilan’s wife, Rona, established a foundation that supports education, and she lectured widely on a subject she knew well—coping with grief—before tragically dying of cancer at the age of 54. To its credit, the exhibit succeeds in soaring above the anguish by also focusing on the incredible survival and painstaking reconstruction of Ramon’s crew notebook and by considering this seemingly sui generis artifact alongside another equally marvelous Jewish cosmonautical diary—the ancient book of Enoch.

The first recorded human mission to space took place 42 years before Ramon’s when a young Russian cosmonaut named Yuri Gagarin exclaimed “poyekhali”—“let’s go!”—just before his capsule was launched into the heavens. Since then, hundreds of people from dozens of countries have traveled beyond the Earth’s atmosphere—though only one whose native tongue was Hebrew. Yet if we consider flights of fancy, countless people since antiquity have been dreaming and writing about reaching the heavens. Arguably, the first space journal written in a Semitic language was not Ilan Ramon’s diary but an Aramaic travelogue attributed to the biblical character Enoch.

Enoch cuts an unremarkable figure in the Bible, briefly mentioned in a list of antediluvian “begats” early in the book of Genesis:

When Enoch had lived 65 years, he begot Methuselah. After the birth of Methuselah, Enoch walked with God 300 years; and he begot sons and daughters. All the days of Enoch came to 365 years. Enoch walked with God; then he was no more, for God took him. (Genesis 5: 21–24)

Despite this rather colorless vitae, ancient Jews were fascinated by Enoch, and they latched onto a few tantalizing clues in the biblical text. Most importantly, the Bible never states that Enoch died, merely that after having walked with God, “he was no more.” Secondly, the span of his years was significantly shorter than his antediluvian peers (not to speak of his famously long-lived son) and identical to the days in the solar year. Finally, he was born in the seventh generation after Adam, which seemed significant.

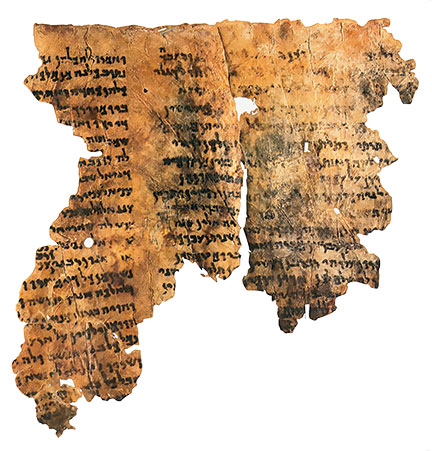

In the third century before the Common Era, Aramaic writings began to circulate that narrated the visions and teachings of Enoch who, although born of woman, had a place among God’s heavenly entourage and was privy to special knowledge, including the complex workings of the solar calendar. According to these texts, Enoch embarked on a number of heavenly journeys, including one inspired by a brief biblical report about “when the sons of God came unto the daughters of men,” yielding giants, “the heroes of old, the men of renown” (Genesis 6:4).

The ancient “Book of Watchers,” a so-called Enochic text, also tells the story of how a group of angels decided to impregnate human womenfolk to calamitous effect and harsh divine decree. From a launchpad located along the lush watercourse at the base of Mount Hermon, Enoch was dispatched on behalf of these fallen angels to beg God for mercy:

And I went and sat by the waters of Dan in the land of Dan, which is south of Hermon, to the west. I recited (to God) the memorandum of their petition until I fell asleep. . . . And in the vision it was shown to me thus: Behold, clouds in the vision were summoning me, and mists were crying out to me; and shooting stars, and lightning flashes were hastening me and speeding me along; and winds in my vision made me fly up and lifted me upward and brought me to heaven. (1 Enoch 13:7, 14:8)

Enoch’s space trip could be fairly described as psychedelic, and it inspired the hallucinatory literature of the Heikhalot (“palaces”)—the oldest surviving genre of Jewish mysticism. After takeoff, Enoch encounters a “wall built of hailstones; and tongues of fire were encircled them all around” and then proceeds into a series of heavenly palaces, where he takes note of curious architectural features like snowy flooring and “a ceiling like shooting stars and lightning flashes.” Seated at the end of the hall on an imposing throne is the Great Glory of God, who answers the Watchers’ request for clemency with a thundering “No!” Yet Enoch’s heavenly tour continues, as angelic guides lead him “away to a dark place,” and he is treated to astounding sights, including “the place of the luminaries, and the treasuries of the stars and of the thunders, and the depths of the ether.” He sees heaven and hell, the mountain of the dead, and a gurgling paradise that recalls the Jordan River tributary where his interstellar journey began.

The Enochic writings present our hero as probing the cosmos in the service of humankind, not entirely unlike an astronaut testing scientific hypotheses in space for the people on Earth below. One ancient Enochic compilation describes itself as the “book about the motion of the heavenly luminaries as they are in their kinds, their jurisdiction, their time, their name, their origins, and their months, which Uriel, the holy angel who was with me (and) who is their leader showed me.” The treatise considers sundry astronomical matters that are used to establish a workable, 364-day calendrical year. Enoch’s conception of the cosmos, with its four climes, seven mountains, and seven rivers, may look, to our eyes at least, deeply mythical, yet the writing has a distinctly scientific cast.

Enoch was remembered by some ancients, such as the writers of the ancient Greek-Jewish work The Testament of Abraham, as “the teacher of heaven and earth.” Actually, as Annette Yoshiko Reed and John C. Reeves document in their meticulously researched Enoch from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, Enoch was evoked in a great variety of ways in a great variety of languages and religious literatures. Enoch was a fascinating figure to many readers of late antiquity and the Middle Ages. The Aramaic texts preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls were translated into Greek and Ge’ez, and canonized by the Ethiopic Church. For other Christians, Enoch was a compelling divine-human hybrid before Jesus; some Syriac Christians called him “the Messiah of the Lord.” There were Muslims who spoke of an ancient prophet named Idris, generally taken to be identical to Enoch, a master of astronomy and medicine who was “the first to take up weapons and to undertake a jihad for the path of God Most High.” The earliest recorded Jewish mystics were inspired by his journeys and attempted to voyage to the heavenly stations he reached. The Zohar was smitten with Enoch and his book and enamored by the treasures of divine knowledge God bequeathed to him. And, of course, Enoch proved to be irresistible to later Christian kabbalists, occultists, and early modern antiquarians. William Blake depicted him as the human conduit of divine artistic creativity.

Notwithstanding the many guises in which Enoch appears in Reeves and Reed’s collection—from prophet and sorcerer’s apprentice to funeral director—Enoch gained his international stature due to his reputation for interstellar travel and the singularity of vision that it afforded. As one verse in the “Book of Watchers” boasts: “I, Enoch, alone saw the visions, the extremities of all things. And no one among humans has seen as I saw.”

There is something mesmerizing about a person who lays claim to, and is himself genuinely astonished by, sights unseen. Israelis found Ilan Ramon compelling even before his tragic demise, and, in his diary, he seems to have accepted the role of surrogate seer. (Brackets in excerpts indicate text that could not be reconstructed.)

Diary—Ilan Ramon, astronaut.

Launch!

No I couldn’t believe it. Until the moment of the engines’ ignition,

I still doubted it would happen. Despite the last few days in isolation at the Cape. Ever since the fateful discussion on Sunday afternoon—by then we all felt that it was real, and yet—we couldn’t believe it. . . .

T-9 and counting! Now you go out to the roof.Time suddenly seems to race . . .

4,3,2,1. A shaking and strong trembling. . . .

We’re in space!What a launch! Everything so [ ]

so fast . . .

It’s amazing to see the halo [ ] light

as if Earth’s globe is wrapped by another globe.

And how thin it is! And then half-an-hour later

it’s sunrise. The atmosphere gets a beautiful

blue shade. And all at once we pass from almost

complete darkness to the strong bright light of the sun.

Sights [ ] impossible to describe . . .

Travel Diary, the sixth day—FD 6.Today was perhaps the first day that I actually felt that I am

really “living” in space!

I have turned into a man who lives and works in

space. Just like the movies. We get up in the morning and float lightly with twisting movements to the “family room”—

the mid-deck. Teeth, face, and to work. Pick up a bit of coffee

“to go.” To the lab. One experiment, another one, a bit of

tidying and cleaning up . . .

shift change, email,

while watching amazing lightning storms . . .

The cursive hand of this passage is clear and legible, and the diary’s language is authentic, confident, and unassuming. Although a highly trained engineer, Ramon mostly avoids technical jargon and foreign loan words. His Hebrew is unadorned yet eloquent, almost literary; it recalls an older register of the language that is now rarely heard on the Israeli street. Ramon’s descriptions of the shaking of the spaceship’s ascent and the thunderstorms on Earth he witnesses from the heavenly windows sound like modern Hebrew renditions of the book of Enoch preserved in the Dead Sea Scrolls. Even when the subject matter is scatological, the text retains a Hebraic dignity—Ramon “urinates” in his astronaut’s diaper, he does not “make pipi,” as in the vulgar convention.

The millennia-long survival of Hebrew and its appearance in a 21st-century diary from outer space is, itself, nothing short of miraculous. But the true wonder is how the exhibit’s ancient and modern artifacts made it, respectively, “through time and space” into the glass cases on the gallery floor of the Israel Museum. If we are to take the word of the book of Enoch, which we most certainly should not, the work was transmitted by its primordial protagonist to his son, Methuselah:

Now, Methuselah, my son, I shall recount all these things to you and write them down for you. I have revealed to you and given you the book concerning all these things. Preserve, my son, the book from your father’s hands in order that you may pass it to the generations of the world. (1 Enoch 82:1)

Still more absurd is the so-called ancient astronaut hypothesis, which claims that humanity originated with extraterrestrial life arriving on spaceships and according to which our very own Enoch and his fallen angels played a signal role in Earth’s colonization.

Yet the West’s recovery of the ancient Enochic writings, at least as it is recounted by its central actor—the Polish priest and philological phenomenon Józef Milik—sounds only slightly more realistic than an Indiana Jones plotline. After centuries of suppression of the book of Enoch on the part of the Catholic church, tantalizing hints in early modern scholarship, a forged 17th-century false start, and then the 18th– and 19th-century recovery, editing, and translation of the Ethiopic Enochic corpus preserved by the Abyssinian church, in September 1952, Milik identified a few fragments of an original Aramaic Enochic text as part of the “heterogeneous mass of tiny fragments” unearthed by the Ta‘amre Bedouins—the tribe that had found the Dead Sea Scrolls at Qumran. “Towards the end of the same month,” Milik writes, “I had the satisfaction of recognizing other fragments, while I was personally digging them out of the earth which filled Cave 4 and before they had been properly cleaned and unrolled.” One of the more celebrated scholarly figures of the mid-20th century—TIME magazine christened him in 1956 as “the fastest man with a fragment”—Milik pieced together what he believed to be seven ancient manuscripts making up an “Enochic Pentateuch.” It was one of the great feats of Dead Sea Scrolls research, and it is thanks to these efforts that one can squint in the faint gallery light and make out the expertly transcribed square characters comprising the Aramaic word for trees, ilanin.

As for the path taken by Ilan Ramon’s journal into the Israel Museum exhibit, this too involves the discovery of fragments on the part of natives, the patient, brilliant efforts of steady-handed experts, and factors that are hard to describe without resorting to words like “miraculous.” But first, let us consider the last page of the diary, which, like the Enochic claim of family transmission, is also addressed to kinfolk, in this case Ramon’s wife:

Rona, I had fun opening your email in the evening

and reading what you wrote!

Tomorrow I’ll tell you to write to me every day!

It’s important. Love you, love you all.

The whole four-and-a-half years that we waited

and wished for this moment—suddenly they all seem like

nothing!

It was worth it! I hope you

feel that way too. What an experience! . . .

This floating. Beautiful Earth.The fragile atmosphere. The company here. I’m speechless.

Rona’s name appears at the top right corner of the page, and the text refers to previous correspondence. It is not uncommon for a diary entry to be written to someone without the author intending for it to reach the addressee. Yet it is overwhelming to contemplate how, ultimately, this accidental postcard arrived at its destination after surviving the fiery cataclysm of the Columbia disintegration; falling miles through the clear blue sky; dropping onto an open field in St. Augustine County, Texas; then being picked up by a Native American tracker and transferred to the U.S. authorities, who gave it to Rona Ramon, who brought it back to Israel where it was reconstructed and deciphered.

Like the Enoch fragments, Ramon’s space journal had its forensic hero, two in fact: In order to ensure that the crumpled and decaying mass of papers would not degenerate further, Michael Maggen, the head of paper conservation at the Israel Museum who has conserved other Hebrew treasures, including the Aleppo Codex and a number of Dead Sea Scroll fragments, sterilized the diary with thymol to kill any microorganisms that might have taken root, and then, working under a microscope, painstakingly separated the pages with tweezers and a fine spatula. The diary was then given to Sharon Brown, a forensic expert at the Israel Police Department’s “Questioned Document Laboratory,” who deployed advanced digital technology and old-fashioned detective work, to reconstruct the text. A partial facsimile of the reconstructed diary (reproducing eight out of the original 22 handwritten pages) has been created, along with the exhibit catalog, which includes an annotated edition of the text.

Ilan Ramon’s diary has a national significance, which is why, in the absence of a criminal inquiry, the Israeli police still devoted considerable resources to its reconstruction.Yet it is a deeply personal document, a letter from a rocket man who, lonely out in space, missed the Earth and his wife. Appropriately, the journal breaks off with the kind of domestic chatter that binds lovers together, even across impossible distances:

The food—I started eating a bit more

The kosher food—is not bad at all Mediterr[anean] chicken

Tomorrow we have half-a-day off

Take it easy!

And tomorrow—we’ll talk! I’m dying already

To see you all—and for you to see me.

Good night.

I am going to sleep late

[ ] than six hours.

Suggested Reading

Zionisms Abound

Gil Troy and Allan Arkush on Troy’s new book, The Zionist Ideas.

The Red Beret and the Rabbis

What has happened to the Religious Zionist rabbinate?

Letters, Winter 2021

Et Tu, Jewish Review?, The Akedah Conundrum, Crazy Rich Mizrachim?, Josephus’s Jonah, and More

The Closing of the American Mind Now

Thirty years ago, a book was published that hit, in the words of the New York Times, “with the approximate force and effect of what electric shock-therapy must be like.” How has it held up? And what does that have to do with the Bible?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In