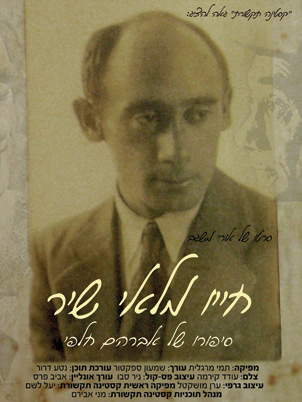

A Cipher and His Songs

If you are a lover of Israeli music then you certainly know Avraham Halfi (1906–1980), though perhaps not by name. The late Arik Einstein’s silky renderings of Halfi poems such as “Atur mitzchekh zahav shachor” (Your Brow Is Crowned with Black Gold), set to music by composer Yoni Rechter, are among the most popular Israeli recordings ever.

As Uri Misgav’s recent documentary about the poet shows, Halfi himself was something of a puzzle. A writer of bewitching intimacy, he nevertheless refused to describe himself as a poet or read his verse in public. He called himself an actor and had a long and successful theatrical career, with a late cinematic turn in the dark, absurdist 1972 film Floch, written by the distinguished playwright Hanoch Levin. An inveterate ladies’ man—the documentary reveals the identity of the muse of “Atur mitzchekh,” the wife of one of Halfi’s friends—he was striking to look at though hardly conventionally handsome, with the stylized eyes and mouth of an African mask and a nose described by one of his friends as “an ad for an Idaho potato.”

A clown, a dandy, a bachelor until his seventies when he married an actress four decades his junior, Halfi remained even to those who knew him a kind of cipher. He was, says one of his fellow actors, “the man across the street, disappearing around a corner.” In his memoirs, the poet Natan Zach recalls Halfi in the 1950s spouting apocalyptic, mystical prophecies in the cafés of Tel Aviv, while in the film Zach rumbles about the surprise he and so many of Halfi’s friends experienced when, after Halfi’s death in 1980, they first learned that he had an adopted daughter. Halfi faced outward, a gifted comic performer, and inward, a lyric poet of resonant privacy, and it is still not entirely clear who stood, Janus-faced, between the two.

Misgav’s film joins a small flood of recent documentaries that explore Israel’s literary past, including Yair Qedar’s Ha-ivrim (The Hebrews), an ambitious series about modern Hebrew writers from Chaim Nahman Bialik to Yonah Wallach, and Hagai Levi’s more uneven Ha-mekulalim (The Accursed), which treats Wallach and other avant-garde culture heroes such as Pinchas Sadeh.

A note of nostalgia runs through these projects, whose directors tend to decry the loss of a bygone humanistic literary culture. Misgav, a journalist and critic (the film is his first), says that in recovering Halfi’s story he felt he was entering “a forgotten world, a world of poetry and art and high culture.” Speaking with me this summer, Qedar used nearly identical language in describing the impulse behind his film series: “I felt I was dealing with a world that was disappearing, a world in which literature and art were central to it, a world of high culture.” Levi ends the first episode of his film with the rueful judgment: “There are no more people like that today.”

Yet this desire to rediscover and celebrate the culture heroes of past generations, reinterpreting them for a contemporary audience, is, I would argue, itself a clear sign of Israeli culture’s continuing vitality. I attended the Jerusalem premieres of Qedar’s new films on the novelist and literary conscience of the second aliyah, Yosef Hayyim Brenner, and the religious poet Zelda, both times along with standing room–only crowds.

The question in the case of each of these documentaries is how and to what extent film can illuminate the life and work of a writer. In the case of a novel, film-makers can always retell the story, but a successful film is often as much an excuse not to read the book as an invitation to do so. Relations between film and poetry are by nature less inherently competitive. Qedar’s films especially delight in using cinematic resources—imagery and voice, music and animation—to enact the adventure of reading a poem.

Yet the documentary impulse eventually halts before the enigma of the poet’s personality and the sufficiency of his or her poems. This is certainly the case with Misgav’s film, which amuses and entices but cannot explain Halfi or the smoldering confidences of his verse. His poems are movingly revelatory, but what they reveal are further secrets, pregnant silences, reservoirs of unspoken loss. As he writes in a poem that turns the Eden of the Bible, in which Adam and Eve “heard the voice of the Lord God going about in the garden” (Gen. 3:8), into his own anti-paradise (in my translation):

I saw how dreams darken.

They hung like birds

on the ends of the branches of the tree.

Darkening.

My voice then went about in the garden—

but was unheard amidst the rustling

of the thirsty grass.

And it didn’t know how to say the things

their life had breathed deep into my body.

And so it died among its silences

and didn’t tell.

One senses that this unspoken sorrow and the atmosphere of solitude it engendered are rooted in the traumas of Halfi’s early years. His mother died when he was three. As a child, he fled with his father from the Polish city of Lodz to Ukraine during World War I, barely surviving a pogrom. Yet, as the film notes, we know very little of Halfi’s life before he arrived in Palestine in 1924 at the age of 18, not even his exact birthdate. Like many immigrant writers of his generation he kept the story of his life in the shadows, and it seeps up like dark water in his poems.

At one point in the film, Zach, who was himself born in Berlin, identifies Halfi as one of these “children of two motherlands,” in Lea Goldberg’s phrase. “It was a one-of-a-kind generation,” Zach growls. “I hope it will never return.”

To read two poems by Avraham Halfi, translated by Leon Wieseltier, click here.

Suggested Reading

Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

More than a shtadlan.

EUGENE NADELMAN: A Tale of the 1980s in Verse

"Our tale's debut / Takes place in 1982 / When I, for one, if not exactly / A double of our leading guy / Was like him, bookish, awkward, shy." - Coming of age in iambic tetrameter.

Letters, Summer 2020

Contradiction?, The Missing Poll, Golden Books, Heroic Acts, and More

Brave New Bavli: Talmud in the Age of the iPad

The Talmud was hypertextual before we had the word. ArtScroll's new app is only the beginning.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In