Montefiore and the Politics of Emancipation

In March 1846, Moses Montefiore, an unusually tall, clean-shaven, traditionally observant, and inordinately wealthy English Jew, crossed the Dvina river in his luxurious private carriage, braving the thawing ice floes in order to travel along Russia’s notoriously poor roads to St. Petersburg, the capital. His appearance was extraordinary in every sense, and he meant it to be so. He arrived wearing the scarlet uniform of a Sheriff of London, with gold epaulets, a plumed hat, and a sword by his side. Once in the city, he made his way up the ladder of officialdom, first meeting with Tsar Nicholas I’s important ministers and, ultimately, with the Tsar himself.

Montefiore encouraged Nicholas, who had ruled for decades over millions of Jews but had never before spoken to one, to follow the example of Western European countries and grant the Jews of his empire equal, or at least greater, rights. The officials and the Tsar himself resisted any such ideas, complaining about the baneful influence of the Talmud, the Jews’ self-segregation through clothing and language, and their continued involvement in questionable economic practices such as smuggling and selling liquor to peasants on credit.

During his stay in Russia, Montefiore’s fellow Jews celebrated him enthusiastically. In St. Petersburg, he met with delegations of Jews from across the Pale of Settlement and prayed with Jewish soldiers in the capital’s barracks. Afterwards, on his way home, the 30,000 Jews of Vilna and the 36,000 of Warsaw welcomed him as a hero if not something of a messiah, the political futility of his visit notwithstanding. Montefiore’s trip to Russia became part of the folklore of Russian Jewry, retold for generations, with each new version diverging further from reality.

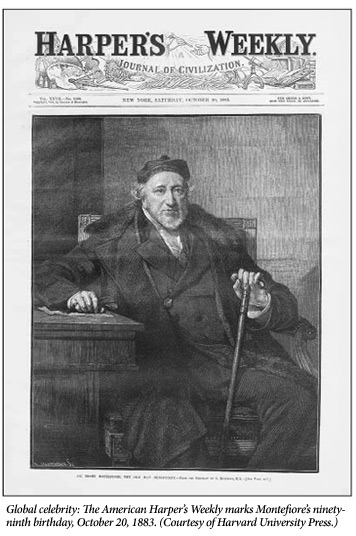

Very few people tell these stories anymore. Famous in his own day as an international advocate for the Jews, who journeyed on their behalf to Egypt and Constantinople, Russia and Palestine, Morocco and Roumania, Montefiore has mostly disappeared from the historical memory of contemporary Jewry. Today, his name usually brings to mind nothing more than a hospital in New York, a windmill in Jerusalem, or perhaps a local old age home. Why has such a towering figure been virtually forgotten?

The answer to this question has to do with what could be called Montefiore’s “emancipation politics.” Not only have such politics been overshadowed by the Holocaust and the establishment of the State of Israel; they have been discredited to the point that, for many Jews, they seem inconceivable if not ludicrous. This is as much the case in the academic as in the popular Jewish imagination. Scholars of modern Jewish history teach that from the 17th– to the end of the 18th-century, Jews engaged in the politics of intercession or shtadlanut, through which Jewish notables, often “Court Jews,” the privileged but precariously situated agents of absolutist rulers, negotiated on behalf of Jewish communities in distress. This practice rested on what the late historian Yosef Haim Yerushalmi dubbed “the vertical alliance”: Jews in the Diaspora looked to the highest power in the land for legally guaranteed privileges, usually given in the form of charters for individuals or communities, and for protection in times of need. Jews did not enter into “horizontal” alliances with other groups in society since these groups were generally regarded as enemies or economic rivals, or both.

Jewish historians have also described how the turn of the 20th-century marked the beginning of “modern Jewish politics,” the time when Jews began to organize themselves into the kind of ideological and political groupings that were currently emerging in Europe in consequence of the widening of the franchise and the mobilization of the masses. They have recounted how the 1890s witnessed the foundation of organized Jewish liberalism (1893), socialism and Zionism (1897), with organized feminism (1904) and Orthodoxy (1912) soon following. Yet, most of these same historians would be at a loss to come up with a label or rubric for the century between the era of shtadlanut and the modern period. One of the many virtues of Abigail Green’s new biography, Moses Montefiore: Jewish Liberator, Imperial Hero, is that she has given us a vivid picture of 19th-century Jewish politics, which we might call the “politics of emancipation.”

Sir Moses Montefiore was a shining example of the Jewish politics of emancipation: his life virtually spanned the century (he was born in 1784 and died at the age of 101), and he was a political prime mover for over half of it. Born into a Livornese commercial family whose members followed the flow of trade to London, Montefiore made a fortune in the city as a broker and business partner of his wife’s brother-in-law, Nathan Rothschild. He helped to found several major companies in the 1820s. He was also among the first of the Anglo-Jewish elite to be admitted to the Athenaeum club. When Queen Victoria ascended the throne, he was named a Sheriff of the City of London, one of whose perquisites was the uniform he wore to meet Tsar Nicholas. He of course purchased a country estate (Ramsgate, Kent), the sine qua non for entrance into the upper rungs of English society, and ultimately was appointed a Baronet.

What was particularly significant about Montefiore’s early business and political career is that it crossed religious lines. His business partners included Christians, especially Quakers and Catholics. Montefiore contributed to, and participated in general and Christian charities in addition to Jewish ones. In fact, in 1835, after he had decided to withdraw from business, he “for the first and last time in his life . . . contracted for a major government loan” that financed the “final abolition of slavery in the British Empire.” This was “bad business but very good politics”; for it demonstrated “his place at the heart of Britain’s philanthropic and abolitionist nexus.” In short, Montefiore entered into “horizontal alliances.” There was a high degree of genuine cooperation, even friendship, between elite Jews and elite Christians. Montefiore’s friends aided him and his fellow Jews by electing him Sheriff.

Emancipation also altered the “vertical alliance.” This is not to suggest that Montefiore and his collaborators fought for Jewish emancipation or political rights in public. They decidedly did not. “The campaign itself was conducted largely behind closed doors—at meetings called in private houses and at political dinner parties, where Montefiore, Goldsmid and Rothschild (and their wives) hobnobbed with the great and the good.”

In view of this kind of collaboration, and for other reasons as well, it would be wrong to say that this campaign was like the politics of the previous period. Montefiore was not a “Court Jew”; he was a subject of the British Crown engaged in elite politics in an age of elite politics. True, he perpetuated the vertical alliance in looking to the state to remove the Jews’ remaining disabilities, yet the state he addressed was not comprised of a sole ruler with the power to banish him at a moment’s notice. It was a constitutional monarchy with a Parliament and functioning democratic institutions—however limited the franchise and corrupt some of the institutions. Montefiore and his collaborators were not asking the sovereign for a favor; rather, they were petitioning Parliament and lobbying its members for a favorable vote. Montefiore carried on public advocacy and closed door politics, both of which were and remain the standard practices of democratic politics.

What really made Montefiore famous, however, was not his domestic politics but his travels and sustained intercession on behalf of Jews elsewhere, a commitment that derived in the first instance from his faith. Montefiore was the sort of believing, though non-intellectual Jew, typical of Anglo-Jewry. His Jewish education was limited to the Bible in English and the liturgy. He had little Hebrew and even less knowledge of Talmud and Rabbinic literature. Yet he was a fervent believer and his arduous pilgrimages to the Holy Land in 1827 and 1839 deepened his faith and strengthened his commitment to his fellow Jews. Montefiore, Green writes, had spent the ten years prior to his first trip “refashioning himself as an English gentleman,” but “he now shaped himself consciously as a practicing Jew” and underwent a “spiritual rebirth.” Upon his return to England, he immersed himself in synagogue (the Spanish and Portuguese Bevis Marks) and community affairs. He became President of the Board of Deputies (1835) and empowered a committee to write a constitution to place it on “a formal footing”: it would have regular financing from the constituent congregations and would “assume sole responsibility for the political welfare of British Jews.”

When the Jews of Damascus became the victims of a blood libel in 1840, Adolphe Crémieux came to London on behalf of the Parisian Central Consistory to seek the help of Montefiore, whom he saw as the man best fit to represent Anglo-Jewry in the Middle East. Montefiore set sail for Egypt alongside Crémieux with the blessing and backing of the English authorities. So began his efforts as the defender or advocate of the Jews. In that capacity he was to make four more trips to the Holy Land (1855, 1857, 1865, 1875), two to Russia (1846, 1872), one to Rome (1858), one to Morocco (1864), and one to Roumania (1867).

Montefiore’s intervention on behalf of Jews abroad was not merely a humanitarian endeavor but represented an extension of his emancipation politics at home. Montefiore believed deeply in a “gradualist approach to emancipation,” through which states incrementally relieved the Jews of disabilities and granted them additional rights. The Jews themselves would meanwhile learn the language of the country in which they lived, and obtain the skills to function as an integral and increasingly welcome part of the larger society. During his trip to Russia, Montefiore encouraged Jews to learn Russian and broaden the curriculum of their schools at the same time that he petitioned the Tsarist government, and especially Uvarov, the Minister of National Enlightenment, to proceed with legal emancipation. It was precisely his promotion of secular education in Palestine that propelled the ultra-Orthodox to excommunicate him in 1855.

Montefiore’s promotion of emancipation and the Jews’ use of the vernacular did not signify a willingness to exchange Jewish observance for political rights. On the contrary, he declared in his diary, “I am most firmly resolved not to give up the smallest part of our religious forms and privileges to obtain civil rights.” His position was thus identical to that of Chief Rabbi Nathan Adler, who promoted an acculturated Orthodoxy that combined traditional belief and stringent practice with middle or upper class respectability. Montefiore vociferously opposed Reform Judaism in England and “cut his brother dead” when he founded the West End reform synagogue, refusing to speak to him for the last twenty-five years of his life.

The distinctiveness of Montefiore’s politics can be seen by contrasting his methods with those of the shtadlan (community intercessor) and the Court Jew. For the typical shtadlan in Eastern Europe in the 18th-century, there were three methods to approach the powers that be: emotional appeals, including crying and wailing; claiming legal rights on the basis of writs, charters, or other documents; and the presentation of gifts or payments, in other words, bribery. Court Jews who attempted to overturn Maria Theresa’s 1744 decree expelling the Jews from Prague, and who brushed aside the incompetent community intercessors of Prague and Vienna (Maria Theresa despised their wailing), created a controlled network of diplomatic correspondence with court and church officials across Europe. They acted entirely behind the scenes, winning the intervention of the Pope and numerous Archbishops, the Estates General of Holland and the Kings of England and Denmark.

Montefiore worked in an altogether different manner. Green instructively describes his conduct in the course of the “Mortara Affair,” in which a Jewish boy in Bologna had been surreptitiously baptized by a Catholic servant and was subsequently kidnapped by the Inquisition to be raised within the Church:

First, apply for cooperation from Jewish communities overseas; second, publicize the issue as widely as possible and stress the universal aspects of the case; third, reach out to other religious and political constituencies in Britain that were likely to prove sympathetic; fourth, persuade the Foreign Office it ought to intervene; and fifth (if necessary), send a deputation . . .

Emancipation and civil society, voluntary associations and the press, combined with a cross-confessional humanitarianism, had created entirely new conditions for politics. Montefiore was operating in a different world from that of the shtadlan or even of the Court Jew. He not only recognized these conditions but also mastered them. He was a consummate choreographer, recording and publicizing each philanthropic step.

This is not to say that such interventions were always or completely successful. In the Damascus Affair, he and Crémieux succeeded in getting the remaining prisoners released yet they neither conducted the independent investigation nor gained the exoneration they had promised. When Montefiore continued on to Constantinople he did get the Sultan to issue a firman prohibiting the blood libel, but that didn’t prevent the charge from cropping up soon afterward elsewhere in the Ottoman Empire. He succeeded, however, in turning himself into the hero of the day.

Montefiore was fortunate to have the British government on his side. His interventions often converged with British imperial politics. Foreign Secretaries such as Clarendon and Palmerston backed Montefiore’s efforts in the Holy Land and the Ottoman Empire since they thought that they helped to support the Ottoman Empire and enlarge Britain’s sphere of influence. The British did the same for Montefiore’s efforts in Morocco and in Persia, considering the Jews’ rights “as part of the imperial nexus of commerce, Christianity and civilization.” Only near the end of Montefiore’s life, with the Balkan crisis or “Eastern question” of the late 1870s, when Montefiore was in his nineties, did these interests diverge. Montefiore then joined Disraeli as the target of accusations of a Jewish conspiracy against Christendom.

Throughout an astoundingly long career, Moses Montefiore made skillful use of all the available institutions of the new civil society. He added to the shtadlan‘s and Court Jew’s arsenal of private diplomacy a new dimension of public politics. The Jewish political movements at the end of the century were to develop and exploit these public politics in ways that Montefiore could hardly have imagined and, in so doing, they ironically went on to repudiate his legacy and efface his memory.

Suggested Reading

Fiction and Forgiveness

Dara Horn’s novel goes down to Egypt to guide its perplexed characters through a Joseph story.

Pew’s Jews: Religion Is (Still) the Key

Who are the “Jews of no religion” in the much-discussed Pew Research Center's “A Portrait of Jewish Americans”? It’s a question that gets at the deep structures of Jewish life and the inadequacy of many of the sociological methods used to describe it.

History of Mel Brooks: Both Parts

On-screen, Mel Brooks was hysterically funny. Off-screen, he could quickly shift to morose or mean.

Mystical Teachings Do Not Erase Sorrow

In Yehoshua November’s new collection, however, it turns out that the difficulties of being a Jewish poet do not primarily flow from being either Jewish or a poet but from the underlying difficulties of life itself.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In