Pour Out Your Fury

In 1803, at the outset of the vast state-building secularization process known as “mediatization” (deutsche Mediatisierung), the Bavarian government confiscated thousands of volumes from monasteries and transferred them to the State Library in Munich. The man in charge of this operation, the German historian and librarian Baron Johann Christoph von Aretin, discovered innumerable curiosities in the process. The most famous of these was the hitherto unknown Carmina Burana manuscript, a medieval collection of sometimes bawdy poems, tales, and songs. Far less well-known but, as it turns out, equally intriguing was a volume that he described simply as a “Hebrew prayer book with precious illustrations.” In fact, it was a Passover haggadah, but he was right about the illustrations, even if it was for reasons he appears to have missed.

Although its illuminations are exquisite, what makes this haggadah utterly unique is that some of them are also aggressively Christian. For instance, the quotation from Chronicles 21:16 “with a drawn sword in his hand directed against Jerusalem” is accompanied by a Jesus-like figure raising a cross-like sword with one hand and folding two fingers and his thumb into the palm of his other hand to symbolize the Trinity. The same Jesus appears again several pages later when the haggadah beseeches God to “Pour out Your fury on the nations that do not know You.” This time he is capped with a Judenhat and galloping in as the Messiah on a white horse.

The Latin Prologue that precedes the manuscript contains something darker: a detailed outline of the Seder, its laws and traditions, together with several classic (and innovative) versions of Christian anti-Semitism. Almost unbelievably, this and other fascinating elements of the manuscript went unnoticed until nearly 200 years after Aretin jotted his little catalog note.

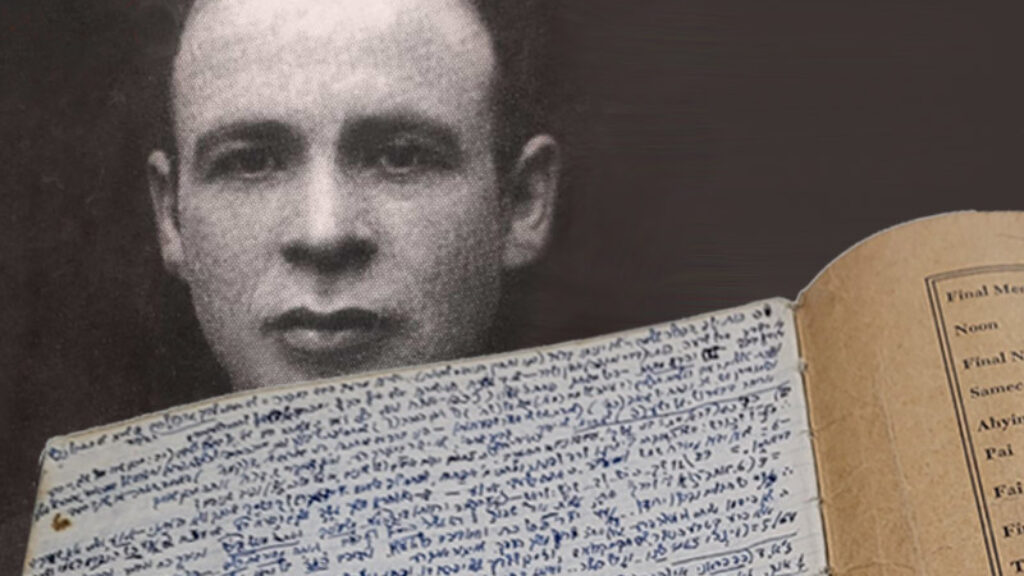

In his moving and surprisingly gripping introduction to The Monk’s Haggadah, Harvard scholar David Stern describes the journey that he and his talented co-editors, Christoph Markschies and Sarit Shalev-Eyni, took in uncovering the mysteries of the manuscript and creating this handsome critical version. (It is the inaugural volume of the Dimyonot series by The Pennsylvania State University Press.) Together with transcriptions and translations of the Prologue, text, and marginalia, the new book contains marvelous essays that make it a comprehensive account of the 500-year life of this mysterious manuscript.

As it turns out, the haggadah had gone through several hands before Aretin’s time. It arrived at the monastery of Saint Quirinus at Tegernsee in southern Germany sometime around 1489, as part of a bequest from the library of Paulus Wann, a priest who preached at the cathedral in Passau. Like all haggadah manuscripts of the time, this one shows every sign of having been written by a Jew, and it is unclear when and under what circumstances it came into Wann’s possession. It may have occurred around 1478, when several Jews in Passau were accused of host desecration (a 16th-century painting by Wolfgang Sauber of the alleged incident shows a group of Jewish men methodically stabbing coin-like Communion wafers bearing the image of Jesus). This led to the forced conversion of 46 Jews to Christianity and the expulsion of the rest from the city. Whether this terrible (but far from unique) episode is what brought the haggadah into Wann’s hands is impossible to know for certain.

In any event, upon Wann’s death, the manuscript arrived at the monastery before being sent by its abbot to Erhard von Pappenheim, one of the many Christian Hebraists of the era, men who saw Jewish texts not merely as targets but as sources of insight. A colleague of the great scholar Johannes Reuchlin and an impressive Christian Hebraist in his own right, Erhard (I will follow the editors in referring to him by his first name) wrote the haggadah’s unique and fascinating Latin prologue before sending it back to the monastery. Here is where things get very interesting and very ugly.

Nearly every element of Erhard’s prologue contributes to its meticulous depiction of a contemporary Ashkenazi Seder. I say nearly because, written in as matter of fact a manner as the recipe for “herosses,” we find the following:

If there is fresh blood, the head of the household sprinkles some drops—more or fewer, depending on how much he has—into the prepared batter, even though, they say, a single drop will suffice. If there is no fresh blood, he grinds dried blood into powder, and then hydrates and sprinkles it as explained previously.

This is, of course, a version of the classic European blood libel, here delivered in what reads like a grisly parody of talmudic legalism, including the distinction between the alleged lekhatchila, or de jure, preference for fresh Christian blood and the bedi’eved, or de facto, acceptance of dried blood in its stead. However, this calumny is soon followed by a much more surprising one:

Once they have set the table with the individual items mentioned previously, the leader of the household sits at the head of the table with his chalice filled with wine before him. Then . . . he takes a single drop from another chalice full of Christian blood, and putting it in his wine, he says: “This is the blood of a Christian child.” Once his own wine is mixed with the blood, he pours a drop into every other chalice.

As David Stern informs us, this second fabrication has no precedent in the history of anti-Judaism. No precedent, that is, unless you consider Erhard’s source for both descriptions: the forced confessions of the Jews of Trent following the infamous Simon of Trent blood libel case of 1475. And who is credited with having translated the Latin protocols of the trial into German? None other than our monk, Erhard von Pappenheim, who was likely present at the show trial.

The fact that Erhard’s Prologue is attached to the manuscript raises interesting questions. In the study of medieval and early modern books, the concept of “authorship” has come to encompass the combined forces that sponsored and conceptualized a given manuscript. In his wonderful study of four illuminated haggadahs from the medieval period, Marc Michael Epstein notes that:

The authorship of each haggadah transmitted a particular ideological, theological, philosophical, historiosophical, political, and social agenda, a way of telling the tale of the relationship of Jews with God, their neighbors, and each other through their exegesis of the narratives of sacred scripture.

What makes The Monk’s Haggadah so fascinating is that different ideological, philosophical, and historical factors were presumably at play at each stage of its production, before it took on its final form.

In order to address the intricacies of all of these factors, each of the co-editors has contributed a chapter or chapters. Sarit Shalev-Eyni, a brilliant scholar of Jewish and Christian art at The Hebrew University, provides a remarkable codicological analysis of the scribal text, marginalia, and illustrations, placing them in their hybrid Italo-Ashkenazi and Christian contexts. Shalev-Eyni concludes that there were at least four pairs of hands involved in the production of the haggadah in its early stages: a talented Jewish scribe; two vocalizers and proofreaders, also Jews by birth, one of whom signs the end of the manuscript as “Joseph, the son of R. Ephraim of blessed memory”; and at least one artist, possibly more.

Shalev-Eyni’s painstaking analysis is as illuminating as the illuminations themselves, and her pointed notes about the uniqueness of the manuscript in the tradition it follows is a crash course in the iconography of the genre. She jumps back and forth from our haggadah to the Murphy, Schocken, London Ashkenazi, and Floersheim haggadah manuscripts, noting similarities and differences effortlessly (or so it reads). The greatest difference of all, the “Christianizing” of Jewish iconography noted above, remains something of a mystery. Were the illustrators Christian? Converts? And who was the patron who commissioned them? Shalev-Eyni simply cannot say for sure, but isn’t it tempting to imagine Wann seizing an unfinished manuscript during the expulsion of 1478 and then subverting its Jewishness with those illustrations? A real haggadah desecration, as it were, in response to the imagined host desecration.

It was Christoph Markschies, a renowned scholar of ancient Christianity at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, who discovered that Erhard von Pappenheim was the author of the Prologue. His essay is a lucid history of Wann, Pappenheim, and the other figures through whose hands the manuscript passed, namely, Ambrosius Schwerzenbeck (the acquiring librarian of the Tegernsee Monastery) and Konrad von Ayrinschmalz (the monastery’s abbot). What he does most brilliantly is describe the Viennese intellectual and theological tradition in which all of these men were trained.

Markschies’ deep knowledge of Christianity and his extraordinary command of 15th-century German humanism give him a precise contextual sense of Erhard’s thought. Thus, where another scholar might be tempted to see something clever in Erhard’s reference to First Corinthians 5:7, “clean out the old yeast so that you may be a new batch, as you really are unleavened,” Markschies is quick to note that “Erhard is not original . . . Rather, he is influenced by entirely basic beliefs of the Christian allegories of the Jewish Passover feast, as formulated in the first generation of Christian theologizing.”

Early Christianity is of course central to understanding the Christian Hebraists’ interest in Passover and the haggadah. The synoptic Gospels and the Gospel of John connect Jesus’ final days on Earth with Passover, and as Anthony Grafton and Joanna Weinberg have pointed out, Protestant scholars would later “claim that the study of Hebrew could be justified by the light it shed on the problems connected with the dating of the Crucifixion.” But Erhard’s interest in the Passover Seder was slightly different. He was most focused on mapping the ritual and liturgy of the Seder onto the dynamics of the Eucharist. Markschies stresses, quite rightly, “The central theological thesis advocated by Erhard in his commentary on Paul Wann’s Haggadah . . . [is] ‘that both Christ at the Last Supper and the Holy Church in the Office of the Mass imitate the aforementioned ritual.’” The paradoxical desire of Christian Hebraists to deride Judaism while at the same time seeking within it the truths of Christianity is displayed more clearly in this haggadah than perhaps in any other document.

For this reason, David Stern calls Erhard’s Prologue “the ultimate Christian Hebraist fantasy,” and his eye-opening essay is a careful reading that places it in the context both of Christian Hebraism and Jewish tradition. Stern leaves not a single intriguing word unaddressed, sometimes with unexpected, even uncomfortable results. For instance, in Erhard’s telling, the sprinkling of the blood at the Seder is accompanied by the enumeration of the plagues and a supplication that “God bring all these plagues and curses upon his enemies, and especially upon the great populace of Christians.” This, of course, will strike many as ironic, even perverse, since the custom of dripping wine at the enumeration of the 10 plagues is generally described in light of God’s lament at seeing any of His creatures drown described in the Talmud (Megillah 10b). In this interpretation, the drops of wine are a symbolic diminishment of our joy. However, Stern quotes the late 14th-, early 15th-century rabbinic authority Rabbi Yaakov ben Moshe Levi Moellin, known as the Maharil, as saying, “It seems to me that the reason [for sprinkling drops of wine] is to say: May He save us from all these [plagues], and may they befall our enemies.” According to Stern this means that “Erhard’s understanding is, then, an authentic reflection of contemporary Jewish belief.”

In his classic Haggadah and History, Yosef Hayim Yerushalmi described the haggadah as “a book for philosophers and for the folk, it has been reprinted more often and in more places than any other Jewish classic, and has been the most frequently illustrated.” Writing in 1973, he counted at least 3,500 editions of the Passover haggadah as having been produced. The Monk’s Haggadah is certainly different from all the others.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Patriotism and Its Discontents

While many Jews embraced the Russian revolutionary cause from the very beginning—four of the seven members of the first Bolshevik Politburo were Jews—the revolution did not embrace them for long.

Think Over My Lesson and Try to Destroy It

When Levinas met a vagabond called Chouchani, he told a friend, “I cannot tell what he knows, all I can say is that all that I know, he knows.” Now that we have dozens of Chouchani’s notebooks, can we finally know what he knew?

Hasidism, Jung, and the Jewish Spiritual Crisis

Carl Jung said that the great “the Hasidic Rabbi whom they called the Great Maggid” anticipated his entire psychology. He learned that from his Jewish student Erich Neumann, whose Roots of Jewish Consciousness was never published until now.

The Lamp of Zion

Over time, the menorah has morphed from a nostalgia-evoking relic of the past to a nation-inspiring symbol pointing forward.

David Z

“It seems to me that the reason [for sprinkling drops of wine] is to say: May He save us from all these [plagues], and may they befall our enemies.”

Of course there's an easy way to stop being an enemy of the Jews... Just stop killing us. We're pretty easy going after that (at least in galut). A more general question that bothers me about the blood libels, and especially as described here. With all the Jewish converts to Christianity (m'shumadim) over the centuries since it first started in the 11th Century, why were they never driven to protest this insane accusation that they drink Christian blood al the years they were Jews? Or do we have records of them trying?

stan

There are such records.