Old Isaiah

There are probably not very many Jews in the United States yearning to see Merrick Garland appointed to the Supreme Court so that their co-religionists might hold four out of its nine seats. Nor, for that matter, is there any reason to believe that a significant number of people now seeking to thwart Garland’s nomination are doing so because he is Jewish. For just about the whole country, his religious identity is utterly beside the point.

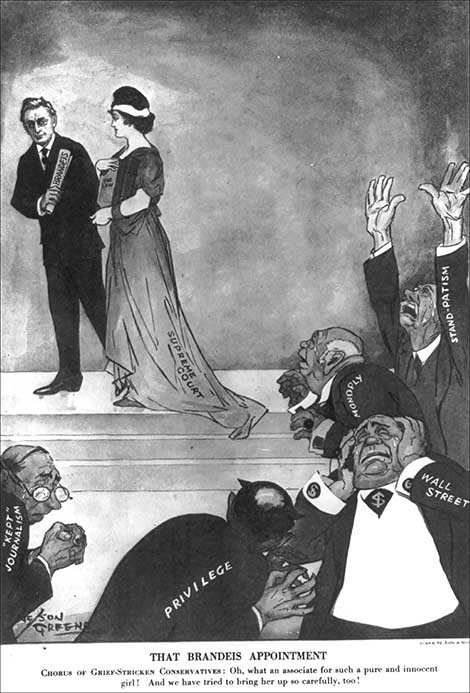

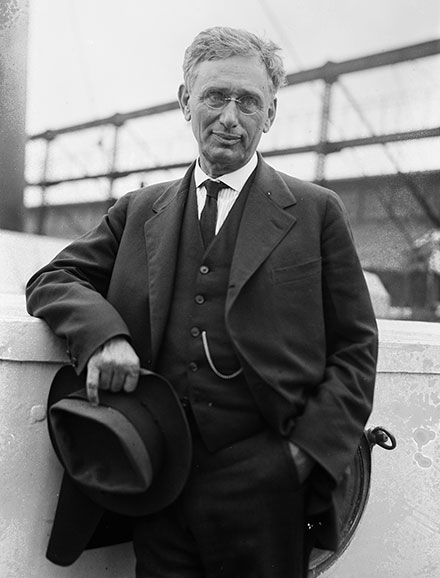

Things were very different a century ago, when Woodrow Wilson became the first president to nominate a Jew for a seat on the Supreme Court. President Wilson’s announcement of his choice of Louis D. Brandeis, “the people’s lawyer,” on January 28, 1916 precipitated a four-month Senate battle. It was the most contentious fight over the confirmation of a Supreme Court justice in American history prior to the 1987 Senate battle over Robert Bork. In his fine new biography, Louis D. Brandeis: American Prophet, Jeffrey Rosen, who covered the Supreme Court for the New Republic and is now the president of the National Constitution Center and a professor at The George Washington University Law School, shows how some of that battle revolved around the fact that Brandeis was a Jew.

George Wickersham, who had been attorney general during the Taft administration and the president of the New York City Bar Association in 1916, attacked Brandeis’s supporters as “a bunch of Hebrew uplifters.” Anti-Semitism was also certainly a factor in the opposition of A. Lawrence Lowell, Harvard University’s president. When Brandeis’s nomination was announced, Lowell, an early supporter of the Immigration Restriction League and one of its national vice presidents, gathered a petition of protest against him that had 55 signatures, including the names of many of the most eminent leaders of Boston’s banking and legal establishments. William F. Fitzgerald, a conservative Boston politician and longtime political foe of Brandeis, wrote that “the fact that a slimy fellow of this kind by his smoothness and intrigue, together with his Jewish instinct can be appointed to the Court should teach an object lesson” to true Americans.

Plenty of the opposition to Brandeis, however, had little or nothing to do with his Jewishness. As Rosen recounts, former President William Howard Taft, who was no anti-Semite, was furious when he heard the news of Brandeis’s nomination. “He is,” Taft fulminated, “a muckraker, an emotionalist for his own purposes, a socialist, prompted by jealously, a hypocrite [. . .] who is utterly unscrupulous [. . .] a man of infinite cunning [. . .] of great tenacity of purpose, and, in my judgment, of much power for evil.” Within days of Wilson’s surprise announcement, Taft also began mobilizing opposition to Brandeis amongst the leadership of the American Bar Association. Together with six other former American Bar Association presidents, he sent a scathing letter of protest to the Senate Judiciary Committee stating that “the undersigned feel under the painful duty to say to you that, in their opinion, taking into view the reputation, character, and professional career of Mr. Louis D. Brandeis, he is not a fit person to be a member of the Supreme Court of the United States.”

Brandeis, however, had a great deal of support from liberal politicians across the political spectrum, who regarded him as one of America’s preeminent social reformers and an important leader of the progressive movement. Progressive Republican Senator Robert La Follette who, as Rosen notes, Wilson had secretly consulted prior to announcing the nomination, applauded Wilson’s appointment, hailing the Brandeis nomination as a historic moment for America. A man who had risen to prominence as a defender of trade unions, women’s suffrage, and a shorter workday for women, Brandeis was the inventor of savings bank life insurance and also pioneered the idea of pro bono public interest work by attorneys. Brandeis earned the sobriquet “the people’s attorney,” achieving fame as one of the champions of the progressive era and as one of the most vocal critics of the excesses of corporate power and the “money trusts.”

President Wilson remained steadfast in his support for his nominee throughout the bitter Senate confirmation battle and, with 56 Democrats and only 40 Republicans in the Senate, the Senate vote on Brandeis’s nomination was never really in doubt. On June 1, 1916, the Senate voted 56 to 28 to confirm his appointment. In the course of the next 23 years, he was to become one of the most important and influential justices ever to sit on the United States Supreme Court.

Brandeis played a singular role in developing the modern jurisprudence of free speech and the doctrine of a constitutionally protected right of privacy, writing some of the most important Supreme Court opinions about free speech, freedom from government surveillance, freedom of thought and opinion, and law and technology. Many of these opinions, originally written in dissent, have become the law of the land and bear upon constitutional questions still confronting us today.

In 1928, in the Supreme Court case of Olmstead v. United States, Brandeis sought to apply the principle of a constitutional right of privacy to changes in electronic technology, such as wiretapping. When the federal government began to tap telephones in an effort to enforce Prohibition, it arrested a Seattle bootlegger named Olmstead, on whose phone conversations federal agents had been eavesdropping for five months. Olmstead protested his indictment on the grounds that wiretapping violated the Fourth Amendment, which guarantees people the right against “unreasonable searches and seizures” of “their persons, houses, papers, and effects.” In what Rosen calls “his visionary dissenting opinion in Olmstead,” Brandeis sought to translate “the founders’ late eighteenth-century views about privacy into a twentieth-century world.” In the age of radio, Brandeis pointed out, telephone conversations were more or less the equivalent of sealed letters, which the Supreme Court had ruled in the 19th century could not be opened without a judge’s warrant. To provide the same amount of privacy that the framers of the Fourth Amendment intended to protect, it had become necessary to prohibit warrantless searches and seizures of conversations over the telephone, even though wiretapping didn’t involve the actual entering of a person’s home. In a remarkably prescient passage of this opinion, notes Rosen, “Brandeis seemed to look forward to the age of web cam and cyberspace, predicting that technologies of surveillance were likely to progress far beyond wiretapping.”

There is some irony in the fact that Brandeis’s Jewishness played such a large part in the struggle over his confirmation, for he had the least substantial Jewish background of any of the eight Jewish justices who have so far served on the Supreme Court. His parents, well-educated German-speaking Jews from Prague, did not belong to a synagogue when they settled in Louisville, Kentucky, nor did they celebrate any Jewish holidays or keep kosher. Brandeis himself was never observant; he had a Christmas tree in his home and famously relished the Kentucky hams sent to him from time to time by his brother Alfred in Louisville. He became a committed assimilationist, a man who could affirm on the 250th anniversary of Jewish settlement in North America that “[h]abits of living or of thought which tend to keep alive difference of origin or to classify men according to their religious beliefs are inconsistent with the American ideal of brotherhood, and are disloyal.”

Yet by 1914 Brandeis had assumed the leadership of the American Zionist movement. This was the culmination of a process that began in 1910 when he mediated the great strike that had paralyzed the garment workers’ industry in New York. It was at this time that he first came into contact with Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe—workers as well as employers—an experience that had a profound impact on him. Brandeis was deeply impressed by their intellectualism and social idealism, and greatly moved by their accounts of the anti-Semitism that had forced them to emigrate from Eastern Europe to America. “What struck me most was that each side had a great capacity for placing themselves in the other fellows’ shoes,” Brandeis wrote. “They argued, but they were willing to listen to argument. That set these people apart in my experience in labor disputes.” At the age of 54, notes Rosen, Brandeis “had gained faith in the Jewish immigrant masses and become conscious of his own Jewishness.”

Brandeis evolved into a Zionist largely as a result of his meeting in 1912 with the Boston editor and journalist Jacob de Haas, who had been Theodor Herzl’s secretary in America and who educated Brandeis about the great man. That same year Brandeis chanced to meet a man who overawed him, the noted Palestinian agronomist and discoverer of “wild wheat,” Aaron Aaronsohn. As a great admirer of Jeffersonian agrarianism and ideals of small government and local democracy, notes Rosen, Brandeis was “thrilled” to learn from Aaronsohn that the Jews were applying principles that he valued highly—“scientific agriculture and self-governing, small-scale democracy”—in Palestine.

Equally important to Brandeis was his encounter with the social philosopher Horace Kallen, who coined the term “cultural pluralism” and who shared Brandeis’s commitment to the liberal values and social idealism of the Progressive movement. As Rosen points out, Kallen’s essays “helped Brandeis to reconcile two ideals—Zionism and Americanism—that he had previously found to be in conflict.” The key to Zionism’s legitimacy for American Jews, as Brandeis came to understand it, was its link to Americanism. In speech after speech throughout 1914 and 1915, Brandeis told Jewish audiences across the United States that his approach to Zionism came through Americanism and that the two were based on common principles of democracy and social justice. This approach led Brandeis to make what would be his famous and oft-quoted

Zionist formulation, inextricably linking Zionism and Americanism together. “To be good Americans, we must be better Jews,” proclaimed Brandeis, “and to be better Jews, we must become Zionists.”

On August 20, 1914, Brandeis assumed the top leadership position in the American Zionist movement. Barnstorming the country, he raised unprecedentedly large sums of money for the Zionist cause and massively increased the number of people affiliated with it. With Brandeis at the helm, the American Zionist movement became a major political force in American Jewish life. Behind the scenes, too, Brandeis performed vital services for Zionism. In 1917 he was “instrumental in persuading” President Wilson to endorse the Balfour Declaration, “after wavering about whether the time was ripe.” This inspired Jacob de Haas to declare, as Rosen reminds us, that “the most consistent contribution to American Jewish history in the twentieth century has been that of Louis Dembitz Brandeis.” Many decades later, after that century has come to a close, this is still a defensible statement.

At the time of his 75th birthday in 1931, Brandeis’s friend Louis E. Kirstein, the Boston Jewish philanthropist, publicly praised him as “a modern prophet,” adding that “I am not the first, nor shall I be the last to suggest that.” Franklin D. Roosevelt famously called him Isaiah, as did members of FDR’s inner circle during the New Deal, and Rosen is evidently disposed to regard him in the same light. As he shows, Brandeis’s deep ethical commitment, rooted in his determination to protect individual liberty and economic opportunity, led him frequently to denounce injustice in a decidedly “prophetic” mode. But Brandeis could pull surprises. On May 27, 1935—known as Black Monday—he and his colleagues on the Supreme Court handed down three unanimous opinions striking down New Deal programs on the grounds that they created unchecked centralized federal power. Brandeis’s support of the unanimous Supreme Court decisions in these three cases stunned FDR—who said in shock, “Well, what about old Isaiah?” Social justice evidently wasn’t the only thing on the prophet’s mind.

Immediately after the announcement of these decisions, Brandeis met secretly with Roosevelt’s adviser Benjamin V. Cohen, one of the most influential architects of the New Deal, and, as Rosen notes, told him to convey a dire “prophecy” to FDR and Felix Frankfurter, Brandeis’s longtime friend and associate who was then a Roosevelt adviser. “You must see that Felix understands the situation and explains it to the president,” Brandeis said. “They must understand that these three decisions change everything,” he warned. Then, in an act of questionable judicial propriety, Brandeis told Cohen to ask Felix Frankfurter to advise FDR that he would have to redesign much of his legislative program. “The president,” Brandeis said, “has been living in a fool’s paradise.”

Brandeis’s secret meeting with Cohen was not his only questionable action. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he used Frankfurter to secretly publicize his political opinions by generating articles and editorials concerning public policy for the Harvard Law Review, the New Republic, and other publications that would appear under Frankfurter’s name. That one of the most renowned and respected justices in Supreme Court history, who has always been portrayed as a paragon of judicial virtue, secretly engaged in extrajudicial political activity that seemed to go beyond the bounds of judicial propriety remains an undeniable part of Brandeis’s judicial legacy that cannot be forgotten or ignored.

In his Epilogue, in which Rosen argues that Brandeis’s legacy remains relevant, he discusses some of the most important legal issues and cases of our time—including the challenge of new technologies to the right of privacy, and the Supreme Court’s controversial 2010 Citizens United decision. On the basis of interviews with Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Stephen Breyer, and Elena Kagan, Rosen is able to document Brandeis’s direct impact on their jurisprudence. All three have been influenced by Brandeis’s judicial opinions and explain why they embrace Brandeis as a judicial model and why Brandeis still matters for them today. Needless to say, you don’t have to be a Jewish justice or even a liberal justice to follow in Brandeis’s footsteps. As Rosen notes, Brandeis’s famous dissent in Olmstead, the 1928 wiretapping case, has been invoked by justices of very diverse judicial perspectives “who are united in their devotion to protecting privacy, from Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy to Ruth Bader Ginsburg.” There is every reason to expect that Brandeis will continue to be as much of a mentor for future Supreme Court justices as he has been for those of the past and present.

Suggested Reading

A Maimonides in Monsey

Maimonides’s only son, Abraham, fought to protect his father’s rationalist legacy. Now a direct descendant has republished his works, and a new Maimonidean controversy is percolating in “yeshivish” circles.

That in Aleppo Once

Does the most accurate biblical text belong in the synagogue, or in a museum?

Red Rosa

A newly published collection of letters shows a new, softer side of Rosa Luxemburg.

“Jacob Gazed into the Distant Future”

In Jacob & Esau: Jewish European History Between Nation and Empire, Malachi Haim Hacohen provides a dense but lucid account of how the history of this typology of sibling rivalry unfolded, first in the later books of the Bible and then, following the invention of a linkage between Edom and the Roman Empire, in rabbinic literature, and, finally, in later Jewish and Christian writings, down to modern times.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In