That in Aleppo Once

Sometime in the 10th century, in Tiberias, Aharon ben Asher and Shlomo ben Buya’a sat down to produce an annotated copy of the Hebrew Bible. Ben Buya’a was responsible for the lettering, while Ben Asher, whose father, Moshe, was also a great master of the textual tradition, or Masorete (from the Hebrew mesorah, meaning tradition), added the notes. These notes are what made the so-called “Aleppo Codex” (a codex is an ancient book rather than a scroll), or, in Hebrew, Keter Aram Tsova (Crown of Aleppo) the most authoritative Hebrew Bible of the Middle Ages. In fact, ben Asher and ben Buya’a’s text didn’t reach Aleppo until the 15th century, and the question of how it got there is one of the several historical mysteries discussed in Hayim Tawil and Bernard Schneider’s new book.

In the Middle Ages, pretty much all Jews believed that the Torah, the first five books of the Bible, had been dictated by God to Moses. But just as important as its reception was the issue of the Torah’s transmission. The troubling reality in ancient and medieval times was that Torah scrolls were not uniform, neither in letters, nor in divisions of sections or vocalization of words. This was a religious predicament, but it was also a scholarly challenge, for the only solution was to investigate scribal traditions, compare the best biblical manuscripts and Torah scrolls, and make informed critical judgments about which readings made the most sense.

This is where the Masoretes came in. By creating a system of marginal signs and notes they enabled the text—and the proper way to read it—to be passed on in as perfect a fashion as possible. To be sure, there had been a concern with biblical accuracy before this—the Talmud says that the soferim (scribes) were known as such because they “count” (in Hebrew, soferim) the letters of the Torah—but it is not until the 8th century that we find systematic treatments of the text, vocalization, and cantillation of the Torah. The codex, basically a book, was simply the best form in which to record masoretic notes, since the scribe can write on both sides of the page and his reader needn’t roll and unroll to find his place. Indeed, Jewish law, which allows only the unvocalized, unpunctuated, and unglossed letters of the Bible to appear in a Torah scroll, almost makes it necessary.

One hundred years after ben Asher and ben Buya’a wrote it, the Aleppo Codex, was in the hands of the Karaite community of Jerusalem. In fact, it is possible that ben Asher and ben Buya’a themselves had been Karaites. Tawil and Schneider take no side in this disputed issue, but it is not implausible, since Karaites, biblicists who rejected rabbinic interpretation and tradition, had a perhaps even stronger theological interest in finding and preserving the purest biblical text than their rabbinic rivals. Moreover, the field of masoretic studies has seen its share of “outsiders,” as most traditional Jewish scholars preferred to focus on the traditional fields of Talmud and halakhah. (One of the greatest masoretic authorities in modern times, C. D. Ginsburg, was a convert to Christianity, and when traditionalist scholars cite his writings they rarely realize that the “C” stands for “Christian.”)

In his 12th-century code of Jewish law, the Mishneh Torah, Moses Maimonides wrote that he “relied on the well-known codex in Egypt, which contains the twenty-four books [of the Bible] that had been in Jerusalem for several years, upon which all relied because it was proofread by ben Asher.” In the 19th and 20th centuries there was a great deal of scholarly discussion as to whether, as tradition had it, this was the same text that later became known as the Aleppo Codex. But as Tawil and Schneider recount, in a nice bit of detective work, Moshe Goshen-Gottstein, of the Hebrew University, conclusively proved that it was indeed the identical text, though by that time much of the Aleppo Codex itself had been lost.

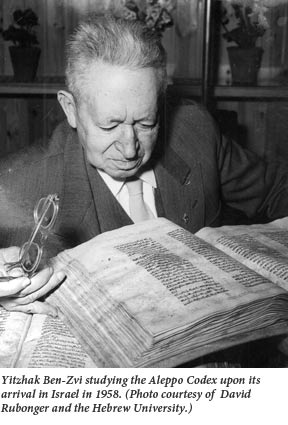

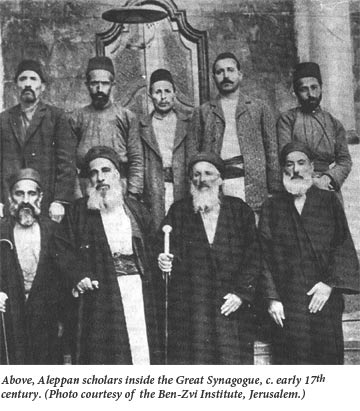

In 1935 Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who later became the second president of the State of Israel, visited Aleppo to see the Codex, which had by then become surrounded by a halo of local history and folklore. It was widely described as the work not of ben Asher and ben Buya’a but of Ezra himself, the biblical scribe who, by tradition, was buried nearby. It was guarded in a safe behind an iron door in the basement of the Great Synagogue of Aleppo, in what was called the “Cave of Elijah,” and believed to be not only holy but magical. Pregnant women prayed near it, and there was supposed to be a curse against anyone who sold it. Both the security measures and the curse may have been inspired by the colorful 19th-century Karaite scholar and forger Abraham Firkovich’s attempt to acquire, perhaps even steal, the Codex. In any event, they did not help Ben-Zvi in his persistent attempts over the following years to convince the Syrian Jewish elders to transfer the Codex to Jerusalem. Although Ben-Zvi was genuinely worried about the safety and preservation of the Codex, nationalism also provided a motive: The Aleppan community had done its job well for centuries, but now that the Jewish home in Palestine had been reestablished, the Crown should return to Jerusalem.

Needless to say, the elders of Aleppo did not see matters this way. In fact, they believed that it was precisely the presence of the Codex that helped protect the community. Even if they could be convinced that the Codex was in danger in Aleppo, they were also terrified by the curse attached to it. Allowing it to leave the community, even if only to be photographed and returned, was regarded by them as no different from selling it.

Intermittent discussions along these lines continued through the 1940s. In 1947, after the UN vote supporting the partition of Palestine, an anti-Jewish riot broke out in Aleppo. The Great Synagogue, which dated back to the 5th or 6th century, was ransacked and burned. Exactly what happened to the Aleppo Codex that day and how part of it was saved is still unclear. The authors discuss seven accounts of how the Crown was saved. Here is the recollection of Moshe Tawil, the chief rabbi of Aleppo at the time (and no relation to the book’s author):

The Crown was accidentally saved . . . Four days after [the pogrom], we entered the Great Synagogue and we saw the ashes of all the holy books. The sexton [Asher Baghdadi] entered and told Rabbi Yitzhak Shchebar that six books were burned and everybody looked at the Crown that was dirty and wallowing in ashes. Immediately, they took the Crown and gave it to a Christian merchant for safekeeping. After four or five months they handed the book to a Jew.

But by this time almost two hundred pages, including most of the first five books of the Bible were missing. Only the last six and a half chapters of Deuteronomy remained. Individual pages were also missing from various books of the Prophets and Writings and the entire books of Ecclesiastes, Lamentations, Esther, Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah are also absent. About forty percent of the original codex was missing.

In 1957 what was left of the Codex was smuggled out of Syria by a man named Murad Faham. According to Faham, Tawil told him that if he succeeded he could give it to whomever he chose. When he arrived in Israel, Faham offered it to now-President Yitzhak Ben-Zvi so that it could be entrusted to the State of Israel. The local Syrian Jewish community regarded the Codex as its property and sued. Although Faham’s story had—like every story about the Codex—some holes in it, the Crown stayed with the State and is today held at the Israel Museum. (It has also now been digitized and made available online.)

For a long time it was thought that the missing sections of the Aleppo Codex had all been destroyed, but Tawil and Schneider are not convinced of this. They collate tantalizing evidence that suggest the missing pages may still survive. A missing page from the Book of Chronicles surfaced in the 1970s, and was later donated by the family that held it to the Ben-Zvi Institute in Jerusalem. According to the family, the page was found on the floor of the Great Synagogue on the day of the pogrom. In the late 1980s, two men in Hasidic garb visited a prominent collector of Judaica at the Jerusalem Hilton, offering to sell him about one hundred pages of what appeared to be the Aleppo Codex for $750,000, before disappearing. And then there is Sam Sabbagh, a Syrian Jew who emigrated from Aleppo as a young man and was living in Brooklyn. For six decades Sabbagh kept a scrap of the Codex from the Book of Exodus in a plastic pouch in his wallet as a kind of good luck charm, or kimeyah. Sabbagh passed away in 2005 and his family donated the fragment, which included the words of Moses on behalf of God to Pharaoh, “Let my people go, that they may serve me,” to the Ben-Zvi Institute two years later. Such stories have convinced the authors that the missing pages need not be lost forever. In 1992 Tawil asked a Mossad agent named Shlomo Gal about the missing parts of the Codex. He was told “Leave the subject alone. You don’t want to know. It’s a very dirty story.” Nonetheless, Tawil and Schneider plainly think that recovering the remainder of the Crown of Aleppo ought to be higher on the agenda of Israel’s cultural and religious authorities.

The story of the Aleppo Codex is dramatic, and, if the authors are right, unfinished. Yet what makes it important is its religious and scholarly significance. At least as of now, virtually all of the five books of Moses are missing from the Codex, making it impossible to check Torah scrolls against it for textual accuracy. But, in a scholarly discovery inadequately discussed in Crown of Aleppo, the Israeli scholar Jordan Penkower was able to find a textual witness to the missing section of masoretic notes recorded in the margins of a Bible printed in Spain in 1490. This new evidence confirmed Goshen-Gottstein’s argument that the Aleppo Codex was indeed the ben Asher text used by Maimonides.

Maimonides had affirmed that the Aleppo Codex was the most accurate text, and if the medieval scholars of Europe had access to it, they would have used it as their guide for writing a Torah scroll. Instead they were confronted with conflicting scrolls and masoretic works, and had to adopt a more eclectic approach. One might therefore assume that since we now know what was in the Codex (which incidentally was very close to the Yemenite tradition), contemporary Torahs should be corrected in its strong canonical light.

The most famous example of how this could be done relates to how the scribe is supposed to write the Song of Moses (Deuteronomy 32). With the exception of the Yemenite community, Torah scrolls today have this song in seventy lines. Yet the Crown has it in sixty-seven lines, as Maimonides in fact ruled. Should Torah scrolls therefore be corrected? One might think so, and some printed Bibles are now produced in accordance with the Crown. Yet when it comes to correcting actual Torah scrolls, scholarly conclusions do not trump religious tradition.

The religious community, the one that cherishes the Torah, studying it daily and reading it publicly a number of times each week, has now been reunited with the most perfect Bible text in existence, the text upon which Maimonides depended and with which religious scholars throughout history would have given anything to spend a few hours. Yet, today, with few exceptions, interest in the Crown is of a historical, not a religious, nature. Our biblical text—mistakes and all—continues to be used, uncorrected.

When, many years ago, I expressed my annoyance about this, I was told “It is true that the Torah scrolls from which we read likely have mistakes, but they are our mistakes.” This still strikes me as profound. It is true that the text of my synagogue’s Torah scroll is not as perfect as that of the Aleppo Codex. Where its letters, line breaks, and spacing differ with what appeared in the Crown of Aleppo, it is almost certainly the case that the Crown is right. Were he alive today, Maimonides would disqualify all non-Yemenite Torah scrolls. But this “less perfect” version of the Torah is what my father and grandfather listened to in synagogue, and it is the version that has been sanctified by the study of countless Torah scholars. It is this that makes it authentic, even more authentic than the Crown that for centuries had almost no contact with the people who would have benefited most from it. Perhaps it is fitting, then, that the final resting place of the Aleppo Codex is not a synagogue but a museum, which is where we place the valued parts of our heritage that we no longer use in our everyday life.

Suggested Reading

Seventy Years in the Desert

At the 1965 International Bible Contest, David Ben-Gurion posed some of the questions. He also asked two to the entire audience: “How many of you are ready to make aliyah to the Land of Israel?” And then, more specifically, “How many of you are ready to come and live with me in the Negev?”

Memory and Terror

How does a survivor of an infamous hijacking piece together her history?

The Other Bernstein

Late August 2018 marks the 100th anniversary of Leonard Bernstein’s birth and the first Yahrzeit of his brother, Burton, who wrote an incredible family memoir.

The Argumentative Jew

The most common understanding of disagreement, in the private sphere and the public one, is that it represents a failure.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In