Inventing American Judaism

This year, the 500th anniversary of the creation of the Jewish ghetto in Venice is being commemorated with lectures, arts commissions, a multimedia exhibition at the doge’s palace, and a production of The Merchant of Venice, the first time that Shylock has ever been brought to life in the ghetto itself. Among the international group of scholars, artists, and writers flowing in and out of the watery city, there’s more talk about multiculturalism than about anti-Semitism and xenophobia, which may account for the oddly celebratory quality of the observances.

But having arrived in Venice from Princeton, recently the site of a landmark exhibition about American Jewish life before the Civil War, I took a more severe view. By Dawn’s Early Light shows that in terms of civil liberties, the contrast between Jewish life in Venice and in America is stark. Both communities were, in part, comprised of Jews driven out of Spain and Portugal by the Inquisition, many of them conversos who were now able to reclaim their Jewish identities. But while the Venetian Jews were confined from the 16th century onward to a small, gated island; restricted to the professions of moneylending, rag trading, and medicine; prohibited from owning real estate; forced to wear an identifying yellow cap; and charged extortionate taxes for those privileges, the Sephardi Jews who arrived in New York faced no such restrictions. Even before the new republic enshrined freedom of religion, the Jews of New York, Charleston, and Newport prospered. As a community, they built synagogues, worshipped freely in them, and observed laws of kashrut and Shabbat; as individuals, they built commercial and familial networks with Jews in Jamaica, St. Thomas, Curaçao, Suriname, and elsewhere in the Caribbean. Unlike the Jews of Venice, whose charter was anxiously renegotiated every decade or so, American Jews participated in civic life, confidently building themselves a future.

Three and a half centuries later, exhibitions on American-Jewish history have an inevitable hint of triumphalism, as the subtitle Jewish Contributions to American Culture from the Nation’s Founding to the Civil War suggests. But as curators Adam D. Mendelsohn (University of Cape Town) and Dale Rosengarten (College of Charleston) show, that influence worked both ways: Being Americans deeply marked the lives of America’s Jews and shaped their understanding of themselves.

Drawing on the remarkable collection of Leonard L. Milberg, a Princeton alumnus who sponsored the exhibition, the curators have taken on the challenge of mounting a show dominated by print: books, pamphlets, newspapers, magazines, prayer books, and even printed sheet music. As an object in a glass case, a text is a stubbornly reticent thing, and walking around it reveals only upside-down print. But the curators, eschewing high-tech bells and whistles, have crafted labels that summon the force fields that gave rise to these objects, and surrounded them with rarely seen portraits and other images, all of which bring the world of early American Jewry to vivid life. The richly illustrated catalog includes 13 original essays on history, politics, theater, religion, and art by an extraordinary group of scholars. Taken together, this exhibition and its catalog give a scope and depth to early Jewish life in America that we haven’t seen before. (Full disclosure: As a Princeton faculty member, I taught an undergraduate course based in part on the exhibition; Princeton University Library, which oversaw the exhibition, generously donated copies of the catalog to my students.)

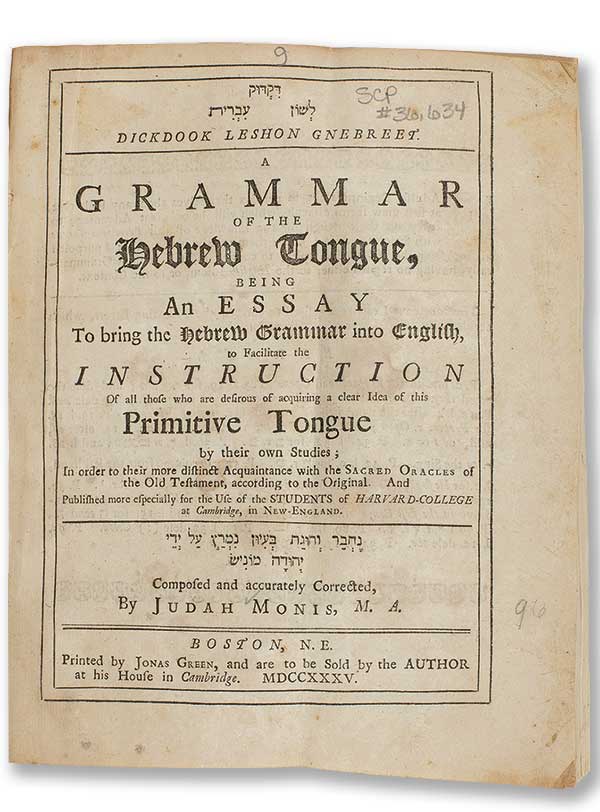

The exhibition opens by exploring the difference it made for Jews to live in a Protestant, rather than Catholic environment. As the late Sacvan Bercovitch argued in The Puritan Origins of the American Self, the Puritans identified with the idea of Jewish nationhood and linked the New World with the biblical Promised Land. The 18th-century Congregationalist minister (and seventh president of Yale) Ezra Stiles was fascinated by Jews and studied Hebrew with Judah Monis, a descendant of Portuguese conversos who chose baptism, at least in part, to take up the first post in Hebrew at Harvard. Monis’s book, A Grammar of the Hebrew Tongue (the quaintly transliterated Hebrew title was Dickdook Leshon Gnebreet), became a standard text at Harvard and other colleges. Moreover, a theory that Native Americans were a lost tribe of Israel led New Englanders to connect Jews with indigenous tribes and Hebrew with their languages.

Christian divines such as Increase Mather were convinced that Jews would play a role in the redemption of mankind, and his 1669 investigation The Mystery of Israel’s Salvation described itself as a “discourse concerning the general conversion of the Israelitish nation.” Some avowed philo-Semites stipulated that Jews must convert. Their efforts gave rise to confident American-Jewish counter-polemics, beginning with The Jew; Being a Defence of Judaism Against all Adversaries and Particularly against the Insidious Attacks of Israel’s Advocate, the first American-Jewish newspaper, published by Solomon Henry Jackson from 1823 to 1825, which is also part of the exhibition.

In the early republic, the line between philo-Semitism and anti-Semitism was blurry; the same missionaries who accorded Jews a crucial role in the redemption of humanity described them, using anti-Semitic tropes, as blind, willful, and materialistic. And what exactly were Jews anyway? Laura A. Leibman’s catalog essay notes the difficulty Jews posed for a census: “sometimes Jews were ‘white’ (albeit of a different religion), sometimes they stood alone in a quasi-racial category between ‘blacks’ and ‘whites,’ sometimes they were a religious group.”

As for Jews and their others, the exhibition portrays the relationship between Caribbean Jews and the human beings they owned as unfathomably complex. Five lithographs drawn from Isaac Mendes Belisario’s Sketches of Character: In Illustration of the Habits, Occupation, and Costume of the Negro Population, in the Island of Jamaica, created in 1837, depict slaves performing in the carnivalesque Jonkonnu festival. Published shortly after the abolition of slavery in the British Empire, these images documented the skill and artistry of black performers even as they fed the taste for images of picturesque blacks and natives. A liturgy for the circumcision of slaves and a handwritten list of mohels attest that Jewish-owned slaves were subject to Jewish laws pertaining to members of a household. Jews, of course, did not have to hold slaves to be complicit in the slave trade. Ties between colonial and Caribbean Jews were tight; communities such as Kingston and Curaçao contributed funds for building colonial synagogues, and hazzanim (who led synagogues before the arrival of trained rabbis) moved from post to post among Caribbean and colonial communities.

By the close of the 18th century, the focus of Jewish life had shifted from the Caribbean to the new republic. Most colonial Jews supported the revolution. In one glass case, we see a miniature of clerically frocked Gershom Mendes Seixas, leader of New York’s Sephardi Shearith Israel synagogue, who famously carried the congregation’s Torah to Connecticut as the British invaded New York. Indeed, most of the city’s Jews preferred exile in Philadelphia to remaining behind and embracing the Tory cause.

After the Revolution, while Caribbean Jews were still seeking to abolish legal disabilities imposed by the British crown, American Jews found their voices as citizens. In the exhibit, we see the famous letter from the Jews of Newport to George Washington celebrating his inauguration and anxiously asking him to guarantee their religious liberties. Quoting the congregation’s letter back to them, Washington vowed that the republic would regard Jews as full citizens, giving “to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance.”

Many individual Jews composed personal letters to American politicians. Journalist, dramatist, and diplomat Mordecai Manuel Noah, who tried (and failed) to found a Jewish colony called Ararat on an island in the Niagara River, sent his account of Jewish history to Thomas Jefferson. The advice he received was more pragmatic than Washington’s. Since prejudice was “disclaimed by all while feeble, and practiced by all when in power,” Jefferson wrote, education was the best way for Jews to achieve “respect and favor.” According to Meir Soloveichik’s contribution “The First Truly American Jew?,” an immigrant from Prussia, Jonas Phillips, wrote to Washington in 1787 to complain about Pennsylvania’s requirement that public officers take a Christian oath. There is no reply on record, and although individual states had such restrictions as late as 1877, the new federal constitution abjured them from the start. Chutzpadik Jews such as Noah and Phillips are given their due in Jonathan D. Sarna’s excellent essay “Subversive Jews and American Culture.”

By the early 19th century, American Jews were publishing their appeals to public figures, to hectoring evangelists, and to one another. Uriah P. Levy, who would become the first Jewish commodore in the Navy despite having been court-martialed six times, published a pamphlet against flogging in the Navy in 1849, which appears in the show twice: once under glass, and again, in an exquisite full-length portrait, gripped tightly in Levy’s hand.

Another pamphlet on display is a speech by the pioneering feminist Ernestine Rose. A rabbi’s daughter, born in Russia in 1810, theyoung Ernestine Potowski sued for emancipation to avoid an arranged marriage and “found a degree of financial freedom by inventing a room deodorizer.” Later, she married a follower of the utopian socialist Robert Owen and emigrated to the United States. Even Ernestine Rose’s radical choices—choices we associate with the post-1880 waves of immigrants from Eastern Europe—were available to American Jews well before the Civil War.

Between 1800 and 1860, while the general population of the United States increased sixfold, the number of American Jews increased 60 times over, from 2,500 to at least 150,000, mostly due to immigration from Prussia, Bavaria, and Central Europe. Despite this phenomenal growth, Jews still amounted to less than half of one percent of all Americans and were widely dispersed among several hundred localities. Rates of intermarriage were high (perhaps as much as 25 percent), missionaries pressed on, and by the mid-1820s, those who were discontent with traditional prayer services became more vocal. Young men in New York and Charleston demanded a variety of reforms, including earlier and shorter Shabbat services, prayers in English, sermons, and a more democratic governing structure. When their demands were refused, they founded their own synagogues. By 1830, the authority of the older institutions, once the cement of the Jewish community, began to erode, and, for the first time, they had to compete for members. Even among traditionalists, this provided a powerful incentive to adapt to the practical needs of Jewish Americans.

With the authority of the synagogues diminished, the Jewish education of both boys and girls was increasingly placed in the hands of women. Prominently featured in the exhibition is Rebecca Gratz, who, following a Protestant model, founded the first Jewish Sunday school, as well as the Female Hebrew Benevolent Society, in her native Philadelphia. Gratz, painted at 50 by the eminent Thomas Sully (she looks a radiant 30—a student of mine dubbed it the “Botox portrait”), collaborated with other Jewish women to adapt Christian catechisms and Bible stories for their children. In an 1838 letter about her new Sunday school to her Christian sister-in-law, Maria Gist Gratz, who was the niece of Senator Henry Clay, Rebecca Gratz suggests that they exchange “meditations” on Bible readings and swap advice on religious education.

A few years later, Charleston-born Penina Moïse became head of religious education at the city’s leading synagogue, Kahal Kodesh Beth Elohim. An advocate for famine relief in Ireland and other causes, Moïse was also the first American-Jewish woman to publish a volume of poetry. Many of the 190 hymns she wrote became staples of the Reform liturgy into the 20th century. But Moïse’s lyric poems, along with most of the other literary efforts by antebellum Jews—even those by the eminent Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise—have fallen into obscurity. The exhibition successfully makes the broad point that 19th-century Jewish writers such as Rebekah Hyneman, Marion Hartog, and Nathan Mayer drew upon their Sephardi heritage and Jewish history more generally in their writings, but it does not quite succeed in giving visitors a sense of the literary texture of these works. (Future iterations of the show, such as the one that will be on display at the New-York Historical Society from October 28, 2016 to February 26, 2017 might consider doing just that via an app or audio guide.) We get a somewhat sharper view of Jews active in the theatre as dramatists, performers, and impresarios. In one striking photo, the chameleonic, sexy stage actress Adah Isaacs Menken poses in a full-length bodysuit.

Shari Rabin’s fine essay “People of the Press” shows how periodicals unified America’s Jews by providing news about the nation’s synagogues, ads for products and ritual services, and notices by those seeking a spouse or a missing relative. But even as they connected Jews to one another, journals such as Isaac Leeser’s The Occident and American Jewish Advocate (founded in 1843) and Isaac Mayer Wise’s The Israelite (founded in 1854) battled over how exactly Jewish texts, beliefs, and practices should adapt to the new American world.

Leeser, a Westphalian immigrant who was lay leader of Philadelphia’s Mikveh Israel for two decades (and of Beth El Emeth for another decade), was a prominent proponent of traditionalism. Leeser innovated, however, by adapting Judaism to an audience that was increasingly fragmented, weak in Hebrew, and determined to assimilate. In By Dawn’s Early Light he is ubiquitous, and with good reason: Here is his translation of the Hebrew Bible, the first in English expressly for Jews; there, his collected sermons; and over there, his Jewish Miscellany, an anthology of tracts (mostly) by and for Jewish women. To promote piety and Jewish literacy, Leeser started the Jewish Publication Society and found tireless allies among Jewish women such as Gratz and the English writer Grace Aguilar. His support, in turn, enhanced their reputations—and in Aguilar’s case, damaged it when Leeser publicly criticized her focus on conscience, rather than commandment.

Isaac Mayer Wise, a liberal rabbi from Bohemia, used his journals The Israelite and Die Deborah (a German-language magazine for women) to advocate for uniting all American synagogues under one religious authority. The exhibition also features Wise’s Minhag Amerika (The American Tradition), the prayer book he wrote to supplant the differing liturgies of Sephardi, Ashkenazi, and Polish Jews. Its theology is unmistakably Reform; gone are references to a personal Messiah, the rebuilding of the Temple, the ingathering of exiles in Israel, and the resurrection of the dead. Tobias Brinkmann’s contribution “Jewish Immigrants from Central Europe in Antebellum America” tells the fascinating story of Wise’s attempt to hold a conference in Cleveland in 1856 to forge a centralized, national rabbinate. This effort was undermined not by traditional Jews (in fact, the idea of a “Central Religious Council” had been Leeser’s, back in 1841), but by the Reform firebrand David Einhorn, who rejected Wise’s theology for its failure to be authentically universalist.

Einhorn is better known, however, for his opposition to slavery, which in 1861 resulted in his being run out of his pulpit in Baltimore; unfortunately, his blistering sermon against slavery does not appear here. But there’s a more glaring omission in this show. The curators highlight conflicts specific to Jews—with missionaries, with public figures, between traditionalists and reformers—but if Jewish “contributions” are on display here, one would like some detailed assessment of how Jews contributed both to the slave trade and to abolitionism, a movement so deeply enmeshed in evangelicalism that few Jews were comfortable taking an active part in it. In fact, the number of Jews who were high-profile abolitionists—Moritz Pinner, Wilhelm Rapp, Abram J. Dittenhoefer, along with Einhorn and Rose—can be counted on one hand. If Jews share in the glory of American freedom, they also share in the shame of American slavery.

Nonetheless, Northern Jews, of which there were about 125,000, by and large supported the Union, while the 25,000 or so Jews living below the Mason–Dixon line generally supported the Confederacy. Jewish families, like so many others, were divided by sectional loyalties. (Rebecca Gratz lost a nephew, who fought against his own non-Jewish cousin at the Battle of Wilson’s Creek.) The highest-ranking Jew of the era was Senator Judah P. Benjamin of Louisiana, who served the Confederacy as attorney general, secretary of state, and secretary of war; the highest-ranking anti-Semite was the Union general Ulysses S. Grant; and the title of premier philo-Semite must go to Lincoln himself, for his executive order reversing Grant’s infamous General Order No. 11, which ordered the expulsion of all Jews from Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi.

Still, an 1861 discourse vehemently defending slavery by Rabbi Morris J. Raphall shocks, in part because Raphall, an immigrant from Sweden, was a New Yorker. Although Raphall was an idiosyncratic Unionist, his sermon reminds us that there were pro-Confederate Copperheads among Northern Jews, but there were also Unionists among Southern Jews, and Southern Jewish slaveholders had sons who renounced the “peculiar” and heinous institution. As much as sectional identities shaped the lives of Jewish Americans, Jews had before them the choices of every other American and made them in sometimes unexpected ways.

Such choices are beautifully illuminated by co-curator Dale Rosengarten’s essay, “Portrait of Two Painters,” on Theodore Sidney Moïse and Solomon Nunes Carvalho, two Charleston-born, self-taught artists who emerged in the 1830s. Moïse, with his fine brushwork and balanced compositions, was the more accomplished of the two in terms of technique, but Carvalho’s dramatic chiaroscuro portraits and his enigmatic allegory of Lincoln and Diogenes make him a more compelling figure.

As Rosengarten points out, this is more than a contrast of aesthetic styles. Moïse spent most of his career in New Orleans, where he gained a following with men of influence and power; in addition to a striking portrait of Henry Clay, he is said to have painted five governors of Louisiana. He also served as a major in the Confederate Army. Like his brother, Edwin Warren Moïse, at one time Louisiana’s attorney general, the painter married a Catholic (after his Jewish wife’s death) and raised their children as Christians. Though one of his sons became a priest and another joined the Christian Brothers, Moïse himself never converted, and when Salomon de Rothschild visited New Orleans, he wrote that he was impressed by Moïse’s “Jewish heart.”

Unlike Moïse, whose New Orleans career depended on what we would now call networking, Carvalho was an itinerant entrepreneur, inventor, and opportunist. Setting up as both painter and daguerreotypist in Charleston, Baltimore, Philadelphia, and later, New York, he developed a technique for coating daguerreotypes in a clear solution that made them more durable. This innovation brought him to the attention of the explorer John C. Frémont, who in 1853 invited the photographer to document his fifth cross-continental expedition. Steve Rivo’s 2015 documentary Carvalho’s Journey tells the story of this catastrophic mission, during which Carvalho, frostbitten and emaciated, nearly died. Nursed back to health by Mormons, he befriended Brigham Young (alas, no fly on that wall) and witnessed a peace council with the Utah Chief Wakara; he would paint both men as noble visionaries, but the portrait of Wakara, in warmer tones, registers pain and loss.

The son of a religious reformer who owned two slaves, Carvalho supported the abolitionist Frémont when he ran for president as a Republican. When “the Pathfinder” lost the election, Carvalho resumed his work as an artist-inventor until cataracts prevented it. For the rest of his life, he immersed himself in Jewish communal work. Thus, while Carvalho’s western journey was a paradigmatic American encounter with the wild, he appears not to have reinvented himself afterward, remaining an observant Jew for his entire life and helping to found the Los Angeles Jewish community.

Carvalho’s legacy as one of the first to photograph the American West was nearly wiped out in 1881 when most of his daguerreotypes were destroyed in a fire. Rivo’s film documents the moving effort of modern daguerreotypist Robert Shlaer, a New Mexico Jew, to recreate Carvalho’s images based on the few dozen still-extant engravings made from them.

In his Mosaic essay “The Problem with Jewish Museums,” Edward Rothstein argues that Jewish museums have an odd relation to the “identity museum.” Unlike museums about other ethnicities, Jewish museums sacrifice particularism to laud the successful integration of Jews in the United States. By the same token, he writes, Jewish museums tend to avoid the simplification and mythmaking inherent in many identity museums. But By Dawn’s Early Light suggests that Jewish particularism in the United States is unthinkable without unique American institutions such as freedom of religion, a free press, public education, westward expansion, transportation networks, and, arguably, the slave trade. To the extent that Jewish Americans eschew identity myths, it may also be because of the diversity within the Jewish community. This exhibition shows that the tenacity of Sephardi pedigrees and Reform Germanophilia were at once respected and limited: respected, as when Wise’s effort to amalgamate American Judaism into a single minhag Amerika went aground; limited by the pragmatism with which American Jews have, from then until now, found ways of assimilating new Jewish immigrants. By Dawn’s Early Light ends with the Civil War, but of course these trends continued. In 1881, when America’s capacity was strained by massive

immigration of Russian Jews, it was a Sephardi-American poet, Emma Lazarus, who convinced not only Jews, but also the American public, to embrace the “huddled masses” as citizens of the future.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Athens or Sparta?

A new "inside story" of the Israeli military reveals more about the current prejudices of the chattering classes than it does about Israel and its neighbors.

Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

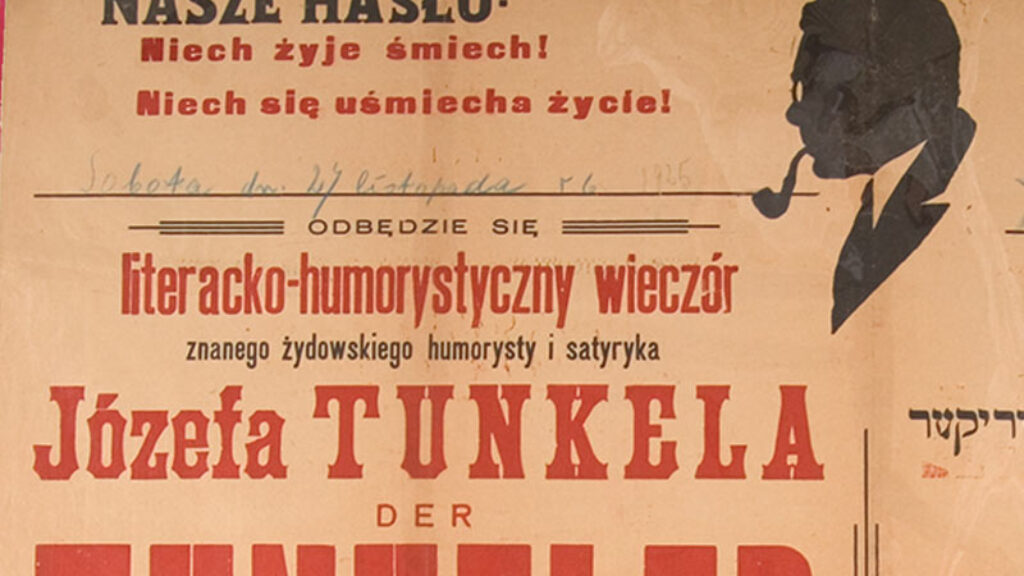

“Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos” and decided to try to make it in Warsaw. A Yiddish satire, translated and with an introduction by Allan Nadler.

Dirty Hands in Difficult Times

Israel's relationship with apartheid South Africa is an inconvenient—perhaps unavoidable—truth.

Between New York and Jerusalem

For twenty-five years, Gershom Scholem and Hannah Arendt, two of the most gifted, influential, and opinionated Jewish intellectuals of the 20th century, maintained a remarkable correspondence. Recently published, these illuminating letters provide a rare glimpse into a relationship that has too often been described as adverserial.

David Z

Excellent article. My only real complaint is about Adah Isaacs Menken. Intrigued by this Jewess of whom I had no knowledge, I looked her up, only to find out... she was no Jewess at all! She married a Jew at one point (and divorced him after some affairs) and apparently was a philosemite who wrote for The Israelite and managed to get herself buried in a Jewish cemetery (in France), but she never even went through a Reform conversion. Not sure she even had a place in this article, but even if you think she did, a mention that she wasn't Jewish was been in order.