Spinoza in Warsaw: Fragments of a Dream

Yoysef Tunkel’s ribald satire, Shpinoza in Varshe: Fragmenten fun a Kholem, first appeared in 1927 in the Warsaw Yiddish daily Der Moment and was reprinted in a 1934 collection of his essays, A gelekhter on a zayt (All Kidding Aside). Nineteen twenty-seven was marked in the Jewish world with an abundance of commemorations of the 250th anniversary of Baruch Spinoza’s death. Unsurprisingly, secular Jewish organizations sponsored most yortsayt events feting the Jews’ most notorious and celebrated heretic.

What did the austere philosophy and life of a 17th-century excommunicated Portuguese Jew who had renounced both Judaism and the Jewish people have to do with early 20th-century Yiddish intellectuals? In the first place, most secular Yiddishists had been “banished from their fathers’ tables” for having departed from Orthodoxy; their identification with Spinoza is easy to understand. Moreover, both the Yiddish and Hebrew biographies of Spinoza emphasized the farfetched notion that his refusal to be baptized indicates that Spinoza never ceased to consider himself a Jew. This may be nonsense, but it was romantic and comforting nonsense for generations of secular Jews. Another reason for Spinoza’s popularity may actually have more to do with his philosophy. For Jews living in tumultuous and uncertain times, experiencing constant displacement, violent persecution, and deep existential anxiety, Spinoza’s insistence that everything is subject to natural law and that the universe proceeds in a fixed and determined manner, regardless of how chaotic things may appear, must have provided a different kind of comfort.

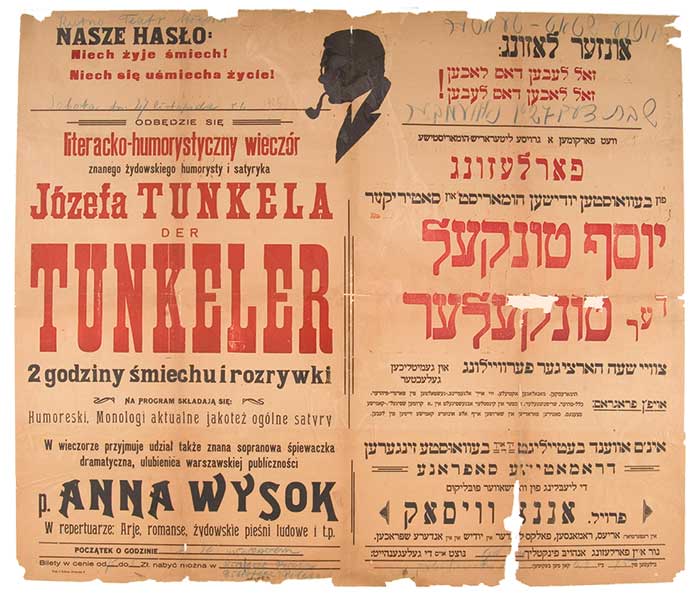

Kutno, Poland, 1925. (Courtesy of YIVO.)

The essay by Der Tunkeler, as Tunkel was known, imagines Spinoza resurrected from the dead and endeavoring to make it among Warsaw’s Yiddish intelligentsia, whose leading lights—many of them self-proclaimed Spinozists—are unimpressed with him. They are unwilling to publish him or even listen to him to at conferences about his own philosophy. Spinoza ends up visiting newspaper after newspaper (each of them a thinly disguised satire of an actual Warsaw Yiddish paper) in a vain attempt to serialize the Ethics, ending in a madcap finale at a scandal sheet. Tunkel’s ironic takedown of would-be Spinozists is of a piece with his skeptical portraits of “high Yiddish culture” in interwar Poland. But the delightfully absurd scenario also satirizes Spinoza himself, specifically his rejection of the existence of a separate and eternal soul, or any other element of transcendence in the universe (not to speak of his humorlessness). The philosopher’s posthumous adventure begins with a letter to the poet and editor Melech Ravitch. Ravitch (néZekharye-Khone Bergner) was the first Yiddish poet to invoke Spinoza as an authority for his own radical secularism. Ravitch’s debut collection of poems, Shpinoze: Poetisheh Pruven (1918) brilliantly rendered the five parts of the Ethics into five poetic motifs in keeping with each part’s central theme. In February of 1927, Ravitch published a long article, Benedikt d’Espinoza Sub Specie Poesia, which took up the entire front page of Warsaw’s weekly literary Yiddish magazine, Literarishe Bleter. Der Tunkeler could not resist the temptation to respond.

Having rested in his grave for 250 years, Baruch Spinoza came to the conclusion that just lying around like that was without telos (takhlis). Every now and then, one ought to get up if only to look around and find out what has been going on in the realm of undying eternity. Having arisen, the first thing he did was to grab a newspaper, in which he happened to read that on that very same day the world was celebrating his jubilee yortsayt.

“How gracious,” he thought to himself, “that the world has not forgotten me; it seems that I decided to resurrect myself at precisely the right time. But now I must give some thought as to my travel plans. Amsterdam is no longer a spiritual center for the Jews, but Warsaw is; I’ll just have to make my way to Warsaw.” He immediately composed a brief letter to Melech Ravitch:

Dear Friend! According to what I have heard, you’ve climbed in the world quite well, but on account of my merits, through your readings and poems. For this, I forgive you. And have no fear that I will be coming to squeeze you. All I would like to ask of you is that you send me a few zlotys so that I can make my way to Warsaw. I’ve heard it said that Warsaw has become quite the grand Jewish center, where I will be able to find more than a few colleagues—say doctor/professors, philosophers—and similarly enlightened folks.

With philosophical wishes,

Your [friend] Borukh

Here is how Melech Ravitch responded:

Of course, do come and travel here, my dear colleague Spinoza, and it is my hope that you will be able to settle in and make a living. Unfortunately, the truth is that right now we happen to have here a plethora of guests: [Zev] Jabotinsky, Shmaryahu Levin, Elisheva, [Chaim] Tchernovitch, Bistritsky, [Vasily] Grossman and many, many more. Nevertheless, I do trust that you remain sufficiently popular so that you have not become entirely oblivious among us (bay undz). It is such a shame, a big shame really, that you did not give us a year’s prior notice so that we might have been able to commission an article of yours for the Varshever shriftn. We might even have found a nice place for you between Professor Leo Finkelstein and Dr. Glicksman. But, as they say, better late than never. Do come.

I await you, as your devoted colleague and friend,

Melech Ravitch

Within days Spinoza found himself hanging around in the Literary Club, schmoozing with its members, every now and then bumming a cigarette in exchange for bringing personal regards from Kant, Hegel, Plato, and Schopenhauer.

During the evenings, he would attend lectures about Spinoza; he would sit, listen, and shrug. Hearing all that was being said about Spinoza but without being able to comprehend what anyone was going on about, simply unable to take it all in with his limited imagination. He did try to intervene a few times in order to insist that he never wrote this, and never intended that. However, the chairmen always stifled him: “Calm down, Mister Spinoza! You’ve been a dust-dweller for the past 250 years, so you must have forgotten what you wrote. When we scholars make a statement, we know of what we speak.”

And so, Spinoza endeavored to receive, at the minimum, a modest honorarium, a cut from the ticket sales for all these many Spinoza-soirées and lectures. . . . The least they could do was help him out. . . . After all, during the entire period that he had remained dead, he didn’t have any need to approach anybody, but now that he had arisen, he required something modest, just in order to live. The community’s “board” answered that they were in no position to give him any money; moreover, surely all the publicity they were giving him should be enough. If not, let him go to the Union of Opticians . . . but Spinoza persisted in sending detailed statements with requests to receive at the very least minimal honoraria, a cut from his translators, his publishers, and those many lecturers.

This matter was then referred to

the Professional Council, but by the time they even began considering his

petition, Spinoza had already begun slowly to die of starvation. He then

decided that he would have to try to find some work from the Warsaw press. With

his Ethics under one arm and his

Theological-Political Tractatus under the other, off he went, drifting

directionless from one editorial office to the other. His first stop was in the

headquarters of the Yarmulke. “And who might you be?” he was asked by the editor

in chief of the Yarmulke.

“Why, I am Spinoza!”

Spinoza? What? The same Spinoza upon whom a cherem was placed?”

“Yup.”

“And on top of that, I’ve been told that you published a Hebrew Grammar!”

“Uh-huh.”

“In that case, be well and get lost . . . mmm . . . well actually, you could hang around with us, but only on the condition that you renounce all of your idiotic ideas and write editorials for us against the Zionists and other evil sinners, may their names be blotted out.”

So, Spinoza picked up his Ethics and the Tractatus and went straight over to the offices of the Big Moment, whose editor welcomed him very cordially. “Sit, sit, Mr. Spinoza, a distinguished guest. Your name is referred to quite often in certain features of our paper.”

“You mean in connection with my [philosophical] writings, correct?”

“Well, not exactly, it is only in our quizzes and crossword puzzles that your unusual name is quite regularly employed.”

“Well then, perhaps you would consider my Ethics for publication?”

“Your Ethics?” the editor began to chuckle, “let me tell you the truth. Your Ethics cannot be published in our pages for a whole bunch of reasons; to begin with, it is way too long for a daily newspaper like ours to serialize; the best we could possibly do is boil it down to two or three summaries, but only if they include corrections since we certainly do not agree with many of your theorems. The best possibility would be to convince a journal to run it, for it is in no way appropriate for any daily newspaper. However, here is one thing we can do: in tomorrow’s paper we will run a warm note about you.”

A very distinguished guest visits the editorial room of Der Groyser Moment

Yesterday, the distinguished Spinoza—who is visiting Warsaw in connection with certain literary matters—came to visit our offices. This eminent guest spent some time engaged in spiritually rich exchanges with the paper’s staff.

With that, Spinoza’s audience with the editor ended abruptly, and with his Ethics in hand, he wandered over to the editorial room of Nekhtiger Tog (Yesterday’s Today).

“Warm welcome,” the editor of the Nekhtiger Tog greeted him. “I assume you have arrived with your delegation?”

“No, I come alone.”

“From Palestine or America?”

“No, no, from Holland.”

Then, in a suspicious tone, the editor asked him, “and, eh, just now, where exactly did you come from?”

“From the offices of Der Groyser Moment.”

“Ah, so it appears you went to them before coming to us, heh? I assume that the editor over there was not pleased with you. So, what do you want from us?”

“I have brought you a work for publication.”

“What does this work deal with? The Jewish Agency?”

“What sort of thing is that?”

“You don’t know? A ‘philosopher’ who doesn’t even know about the Jewish Agency is not someone we can publish.”

“But it’s a good book, my Ethics. Ask around, and you will be told that there are some pretty good ideas there.” “Fine, you know what? We will allow its publication, but on the condition that you add a chapter that deals with some political provocation.”

Well, that shidduch came to naught, so Spinoza went straightaway to the editors of the Horepashnik (Working Class). After having lain in the earth for 250 years, followed by a long day of running all around town, a fatigued Spinoza was only able with great difficulty to climb the stairs to the building’s fifth floor, where the editors of the Horepashnik gave him a mixed greeting. Friendly, on account of his great struggles, and unfriendly on account of his petit bourgeois thought:

“It pleases us to make your acquaintance; you should know that you were the first to articulate the ideology of our Master, [Berlin educator, Heinz] Galinski of our ‘Universalist School’ . . . and so we are in accord with you. We have long been inculcating it in our children. And we have refashioned our folklore in this very spirit. In our ranks, we now declare, ‘If Nature wills it, brooms can fly, Oh Nature, Nature, send some rain, for the children’s gain’; Oh Nature, taste my kompot.

“Granted that this last line lacks rhyme, but it is so deeply in accord with our Weltanschauung that we decided to forsake the poetic aspect. . . . Ah yes, comrade Spinoza, we have much in common; just as you did with the Orthodox in Amsterdam, we have had to put up with a lot from the Warsaw Shomer-Shabbes Society. And yet, we still cannot publish your Ethics. First, because it has a scientific orientation, and we have our own staff writer who runs a piece every Shabbes in the domain of the sciences. Moreover, we heard it said that in your writings you refer from time to time to peoplehood, Jerusalem and so forth, which suggests that it may be the case that you have had an influence on Moses Hess, Ahad Ha’am and others of their ilk . . . but there is one thing we may be able to do for you. Leave your copy of the Ethics with us, and we will hand it over to our comrade Yankev Patt, who will edit and transform it into a book appropriate for children, more suitable for publication in our Horepashaynikl (Little Labor’leh.)”

At that, Spinoza threw himself right out the fifth-floor window and found himself lying in a state of despair, with the Ethics still under his arm. But then, quite suddenly, he noticed in the distance a house with a sign, reading, “Editorial Offices of the Red Grasshopper.”

Yet another editorial office, he thought; one mustn’t tempt fortune, and so he went on in. “Hoorah! A sensation,” the grasshopper-group shouted out upon seeing Spinoza.

“What good stuff can you tell us, Mr. Spinoza?” asked one of that group who specialized in stories about philosophical personalities, thanks to his close acquaintance with Tolstoy and Gandhi.

“I have brought you works for publication in your paper.”

“What are these works called?” asked the editor in chief.

“Ethics and Theological-Political Tractatus.”

“We don’t run that kind of stuff. Perhaps you have some novel theses, say about promiscuity, flirtations, women’s legs, haircuts à la garcon?”

“Nope.”

“Really not? Well, in that case, we ourselves will transform you into a sensation, right boys?”

And so he gave the command to his grasshopper-gang to get right down to work. The following fantastical story appeared, under three large headings:

After being dead for 250 years, he has been resurrected!!!

He had been excommunicated for polygamy!!!

Now he’s a forger of phony diamonds made of glass here in Warsaw!!!

Yesterday, in the offices of the Red Grasshopper, where there is constant tumult and exciting news on millions of topics—there suddenly appeared a man with the name Baruch Spinoza, who had been lying in a cemetery for 250 years. On his way here from Holland, he was kidnapped by a group of pimps in the white slavery trade. He was rescued by the lovely Amalia, who resides at 7 Karmelitzka Street, who soon bore him a child with two heads: one human skull and the other made of cabbage. But it then was revealed that this “Amalia” was, in fact, the [male] assistant beadle of Nozik’s shul. This matter is currently under investigation by the criminal justice authorities.

And then three photographs were appended to this piece, as this important guest was captured by camera from the front, side, and back of his head. Once published, they patted Spinoza on his shoulder and suggested that he leave. Spinoza saw clearly that there was nothing for him to do, so he traveled back to Holland and returned to his eternal rest.

Suggested Reading

Drowning in the Red Sea

Gennady Estraikh said, "It is hardly an overstatement to define Yiddish literature of the 1920s as the most pro-Soviet literature in the world." When Arab riots killed 400 Jews in Palestine in late August 1929, the Yiddish communist press found itself torn between sympathy for the fallen and loyalty to the Revolution.

The Wages of Criticism

The great 18th-century talmudist Rabbi Aryeh Leib Ginsburg never whitewashed his disagreements with other scholars, claiming that most "ruined good paper and ink and embarrassed the Torah." According to a popular rabbinic legend, his downfall came when, in an act of cutting vengeance, the books he had criticized came toppling upon him.

Poisoned Gefilte Fish, Broken Heart

In a characteristic turn of phrase, Der Nister wrote that the realization of the possibility of a land for Jews, where they lived under their own sovereignty would be a “brokhe af doyres” (blessing for future generations). The bitter irony is almost unbearable.

Re-Intoxicated by God

The way out is clearly marked: Intense Talmud study leads to intense study of science and philosophy. Spinoza was (in fact, sometimes still is) a crucial step along the path out.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In