The Hands of Others

How much of the blame for the Holocaust can be placed upon the Arabs? And why is there so much Holocaust denial in the Arab world today? According to Gilbert Achcar, only a small minority of Arabs were committed Nazi sympathizers, while hardly any actively abetted the Holocaust. ‘The Arabs’ as a people, he argues, were not co-conspirators of the Nazis and therefore should not have had to pay the price in Palestine for the genocide perpetrated against the Jews in Europe. That “price,” the loss of their homeland in 1948, is in turn the source of Arab Holocaust denial: “The further that Israel goes in its political and practical denial of the nakba, and the longer Israel continues to exacerbate its consequences, the more Palestinians and Arabs will be tempted to riposte by denying the Holocaust.”

Readers made uneasy by these ideas may be even more ill disposed to give them a hearing when they learn the identity of the author of The Arabs and the Holocaust. Gilbert Achcar is a Lebanese-born socialist, a harsh critic of American foreign policy and of Israel, and the co-author (with Noam Chomsky) of a 2007 volume entitled Perilous Power: The Middle East and U.S. Foreign Policy. Dialogues on Terror, Democracy, War, and Justice. Nevertheless, his newest book is an important work, even—perhaps especially—for those who will not agree with it. Its exploration of Arab sensibilities is thoughtful and illuminating, its condemnation of Holocaust denial humane and principled. Yet no less principled is the author’s steadfast anti-Zionism. The book, although meant to overcome what the subtitle calls “the Arab-Israeli war of narratives,” in fact demonstrates the chasm that divides the leftist Arab intelligentsia from its Israeli counterpart.

Achcar begins his book with a comprehensive overview of the different ideological camps in the Arab world during the era of the Holocaust. He endeavors to show that Arabs responded to Nazism in many different ways, with few apart from radical religious figures like the notorious Palestinian leader Muhammad Amin al-Husseini demonstrating deep anti-Semitism. There was a solidly anti-Nazi liberal intelligentsia, which during the 1930s filled the Arabic press in Egypt and Palestine with criticism of Hitler’s regime on ethical and religious grounds, but also expressed fears that Nazi persecution of the Jews would serve to strengthen the Zionist enterprise. Marxist Arab intellectuals became sworn enemies of Hitler, at least after his June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. Some secular Arab nationalists sympathized with Germany because it was the enemy of the British Empire, which stood between them and their countries’ full independence. But only a few thousand Muslims from the entire Middle East and Africa served in Axis forces, while nine thousand Palestinian Arabs served in the British Army, and hundreds of thousands of Maghrebis fought for the Free French. Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani was, Achcar argues, acting as a nationalist and anti-imperialist, not a Nazi collaborator, when, after being forced from office in January 1941, he called on Axis military support for a short-lived coup d’état.

Achcar begins his book with a comprehensive overview of the different ideological camps in the Arab world during the era of the Holocaust. He endeavors to show that Arabs responded to Nazism in many different ways, with few apart from radical religious figures like the notorious Palestinian leader Muhammad Amin al-Husseini demonstrating deep anti-Semitism. There was a solidly anti-Nazi liberal intelligentsia, which during the 1930s filled the Arabic press in Egypt and Palestine with criticism of Hitler’s regime on ethical and religious grounds, but also expressed fears that Nazi persecution of the Jews would serve to strengthen the Zionist enterprise. Marxist Arab intellectuals became sworn enemies of Hitler, at least after his June 1941 invasion of the Soviet Union. Some secular Arab nationalists sympathized with Germany because it was the enemy of the British Empire, which stood between them and their countries’ full independence. But only a few thousand Muslims from the entire Middle East and Africa served in Axis forces, while nine thousand Palestinian Arabs served in the British Army, and hundreds of thousands of Maghrebis fought for the Free French. Iraqi Prime Minister Rashid Ali al-Gaylani was, Achcar argues, acting as a nationalist and anti-imperialist, not a Nazi collaborator, when, after being forced from office in January 1941, he called on Axis military support for a short-lived coup d’état.

On the other hand, there were several pro-Nazi Arab nationalist organizations, and some of them flirted with fascism. The Futuwwa high school student movement in Iraq wrought havoc during the farhud, the murderous pogrom of June 1-2, 1941, in Baghdad. Another nationalist organization, Young Egypt, adopted a truly anti-Semitic platform in 1939 and organized a boycott of Jewish businesses. This group in fact attracted several young men who would become leaders of the Free Officers who seized power in 1952, including Gamal Abdel Nasser and Anwar Sadat. Achcar tries very hard to minimize the degree to which Young Egypt had a pernicious influence on these two men. Nasser, he notes, left Young Egypt because it was “inane,” and Sadat, although solidly pro-German, never displayed “the slightest sympathy for Nazi doctrine in general or anti-Semitism in particular.”

Islamist movements, Achcar stresses, were far more consistently and vociferously anti-Semitic than secular Arab nationalist forces. Reading anti-Jewish rhetoric in classic Muslim texts in the light of pernicious new ideas emanating from contemporary Europe, the Wahabi fundamentalists of Saudi Arabia, backward-looking Islamic reformers like the Syrian Rashid Rida, and the founders of the Muslim Brotherhood all spoke in terms of an inevitable clash of religious civilizations between Judaism and Islam. They were true anti-Semites who believed Jews to possess awesome economic and political power, and to exercise a corrosive effect on the morals of Arab youth. (Similarly fanatical was a Palestinian village sheikh and armed rebel of the early 1930s named Izz ul-Din al-Qassam, after whom Hamas’ armed wing—and rockets—would be named.)

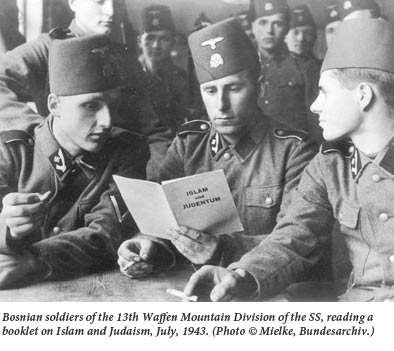

As Achcar makes clear, the most influential of the reactionary pan-Islamists was Muhammad Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem and leader of the Palestinian national movement during the years of the British Mandate. Exiled from Palestine in the course of the Arab uprising against the British in the late 1930s, Husseini ultimately found his way to Berlin, where he met with the highest officials in the Nazi regime, including Hitler, and pleaded with them to support the Palestinian cause and prevent Jewish immigration to Palestine. In Berlin, the Mufti went to work for the Foreign Ministry’s office of propaganda, broadcasting pro-Nazi propaganda to the Middle East on short wave radio. The Mufti knew, and approved of, the Holocaust, and in 1943 raised a Bosnian Muslim division to serve in the Waffen SS.

Husseini plays a central part in Jeffrey Herf’s recent Nazi Propaganda for the Arab World, which draws heavily on transcripts of Arabic Nazi broadcasts, all of them drenched in anti-Semitism, and many explicitly inciting violence. Citing the Qur’an, one typical broadcast called upon Arabs to “kill the Jews wherever you find them.” Achcar acknowledges the Mufti’s anti-Semitism, but he claims that his influence on the Arab and Muslim world was minimal. Bosnian Muslims signed up to fight with the SS not out of any enthusiasm for Nazism but in order to take revenge against the Serbian nationalists who had, earlier in the war, massacred thousands of their compatriots. The SS division that the Mufti raised quickly fell apart, as most of its members deserted to join Tito’s partisan units. Achcar also claims that the Mufti was neither a respected nor an influential leader after 1939, but was hated and feared by his political enemies throughout Palestine, ranging from other patrician families to the radical nationalists of the Istiqlal (Independence) party.

How, then, do we account for the Mufti’s ability to dominate the Arab Higher Committee (AHC), the unified leadership of Palestine’s political parties, even after his departure? Why was he able to stymie Palestinian acceptance of the 1939 White Paper, of which the majority of AHC members approved? And why, despite being unable to return to Palestine after the war, did he remain, even in Egyptian exile, the most prominent Palestinian leader during the 1948 war? On these points Achcar is silent.

The true extent of Husseni’s influence in the 1940s is debatable, but he was, without a doubt, a war criminal. He was guilty at least of collaboration and, as a subject of the British crown, subject to prosecution for treason. The overwhelming majority of Arabs were, however, uninvolved in the Holocaust and innocent bystanders to it. Achcar’s account of this period undermines any argument that what in the Arab world is called the nakba constituted the Arabs’ just desserts for their iniquitous conduct toward the world’s Jews during World War II. Many Palestinians may have hoped for a German victory that would rid them of both the British and the Zionists, but attacks by Palestinian guerillas, and then Arab armies, against Israel in the 1948 War have to be seen in their own terms, not as an attempted extension of the Nazi genocide.

The true extent of Husseni’s influence in the 1940s is debatable, but he was, without a doubt, a war criminal. He was guilty at least of collaboration and, as a subject of the British crown, subject to prosecution for treason. The overwhelming majority of Arabs were, however, uninvolved in the Holocaust and innocent bystanders to it. Achcar’s account of this period undermines any argument that what in the Arab world is called the nakba constituted the Arabs’ just desserts for their iniquitous conduct toward the world’s Jews during World War II. Many Palestinians may have hoped for a German victory that would rid them of both the British and the Zionists, but attacks by Palestinian guerillas, and then Arab armies, against Israel in the 1948 War have to be seen in their own terms, not as an attempted extension of the Nazi genocide.

Arab Holocaust denial was neither immediate nor instinctive. Shortly after the war, the Mufti correctly estimated Jewish losses in the Holocaust as “more than thirty percent of the total number of these people.” During the early 1950s, Arabs frequently acknowledged the genocide though they had little sympathy for Israel. This hint of openness faded as Israel increasingly defined itself in terms of the Holocaust. The Eichmann trial, Israel’s representation of the 1967 War as a would-be second Shoah (though Achcar doubts that Israel was, in fact, in existential danger), and Menachem Begin’s persistent use of Holocaust imagery from the late 1970s onward (the only alternative to invading Lebanon, he said in 1982, is “Treblinka”) dumbfounded Arabs, especially after a mighty Israel conquered the West Bank and Gaza and began to settle it with Jews. Invoking powerlessness while wielding power fueled Arab fantasies of Jewish duplicity, thus encouraging the claim that the Holocaust did not happen, or had been exaggerated.

Achcar’s main arguments are not very different from those of Israeli scholars Meir Litvak and Esther Webman in From Empathy to Denial, an exhaustive survey of Arab responses to the Holocaust. Achcar heaps criticism upon this book, at times unfairly and over minor differences of interpretation. There are, however, at least two important differences in their analysis. While Litvak and Webman interpret the Palestinian cult of the nakba as a mere copy of Israeli Holocaust-centrism, Achcar insists that the Palestinians’ memory of their national tragedy has its own character, wellsprings, and underlying legitimacy. Litvak and Webman also see Arabs, even the secular intellectuals among them, proclaiming the Holocaust and nakba to be equivalent. Achcar, however, insists that he is merely demanding conversation and acknowledgment. He readily grants that the Holocaust, as well as other acts of mass murder and ethnic cleansing, far outweigh anything Israel did to the Palestinians in 1948. But that by no means eliminates his grievance against Israel.

Achcar’s account of the gradual emergence of Holocaust denial in the Arab world calls to mind a parallel process that has taken place in Israel and the Jewish world in general. The Palestinian tragedy was widely known at the time it occurred, and some Israelis assumed a share of responsibility for it. Many Israeli soldiers were witness to, or a cause of, Arab flight. The expulsion of Arabs from Lydda and Ramle was even reported shortly after the fact in Israel Speaks, the New York-based newspaper of the American Friends of the Haganah. During the state’s early years, the plight of Arabs driven from their land and forbidden to return was exposed in the Israeli journal Ha-Olam Ha-Zeh and in a popular book of 1950, Ha-tsad ha-sheni shel ha-matbea (The Other Side of the Coin), by the journal’s editor, Uri Avnery. The expulsion of Palestinians from their village was also the subject of a celebrated and widely-read work of fiction, Khirbet Khizeh (1949), by S. Yizhar. Yet, as Anita Shapira has shown, the fact that some measure of the Palestinian tragedy was due to forced flight was forgotten over time. The flood of immigration into Israel diluted the country’s previously intimate knowledge of the war, and ongoing Arab hostility spurred the creation of a retroactive image of Arab flight as planned by a conniving Palestinian leadership. What might be called “nakba denial,” like Holocaust denial, has been an acquired behavior.

This parallel process of forgetfulness is something that ought to be the subject of discussion among Jews and Arabs, Zionists and Palestinian sympathizers. If Achcar’s book helps to stimulate such conversation, and even lead to honest discussion in the Middle East about the mass exodus of its Jews after 1948, it could do much good. Unfortunately, Achcar’s soothing call for “Cartesian shared reason” is thwarted by his own political agenda. Israel, he claims, is the last “European colonial settler state” that has not recognized and restored the rights of the native population. Even if one accepts the premise on which it rests, this statement is a bit of a stretch—the United States and Canada, for example, have yet to restore North America to Native Americans. Achcar further describes Israel as “a bellicose state that has continued to occupy the territory of its neighbors for sixty years”—not forty (since 1967), but sixty, since its founding. Is the state then, in any territorial form, illegitimate? Must it retreat to the borders of the 1947 United Nations partition proposal? No Arab peace offer of the past fifty years has suggested such a thing.

Underlying these sentiments is the venerable anti-Zionist cliché that Jews comprise a religious community, not a nation, and so do not have a collective right of sovereign self-determination. Achcar sees Arab leaders from Nasser to Michel Aflaq to Yasser Arafat as having undertaken a fundamentally peaceful mission to transform Israelis “from a colonial Zionist population into a non-Zionist religious community enjoying equal rights in a secular Palestine.” Not only does he ignore decades of Arab bellicosity towards Israel and the grim legacy of Palestinian terrorism, but he also conjures away millenia of Jewish corporate existence that transcended confessional boundaries, not to mention the self-definition of the vast majority of world Jewry today.

Achcar is critical of Islamic Jihad and Hamas but sees them as the direct result of Israel’s destruction or delegitimization of secular, democratic, and liberal alternatives. During the 1980s, Israel did, in fact, promote Islamic movements in the West Bank and Gaza as an alternative to the PLO. But Achcar demeans Palestinians, and Arabs as a whole, by denying them agency or moral freedom, and presenting them as mere playthings in the hands of awesome, unstoppable Israeli power. After all, radical Islam has flourished throughout the Middle East without the help of Israel (nor, Achcar’s secularist prejudices notwithstanding, are practicing Muslims necessarily more hostile to Israel than are their secular brethren). Occupation alone does not explain the self-destructive choices that Palestinian leaders have made over the past forty years. The occupied and the occupier each have moral responsibilities, and victimhood does not automatically bestow virtue.

Achcar claims that anti-Zionism is not anti-Semitism because not all Jews are Zionists. Apparently, Jews who are Zionists—the great majority of world Jewry today—are to be condemned. Achcar believes that fundamental critiques of Israel have moved from “the Far Left to the heart of post-Zionism,” and from there to previously committed but now recovering Zionists like Avraham Burg. Leaving aside Achcar’s vast overestimation of post-Zionism’s influence on Israeli or diaspora Jewish society, it is deeply troubling that never once in the book does he offer a definition of Zionism itself. It seems that the word, no matter how conceived, means dispossession and racism. Achcar cannot accept even a Zionism that recognizes Palestinian national rights, that strives to equalize the social position of Israel’s Arab citizens and to foster a stable Palestinian state, while asserting the rights and needs of the Jewish people.

Despite the polemical tone of Achcar’s later chapters, his basic historical argument is sound. The Holocaust was a European crime, for which the Arab world was not culpable. Pro-German sentiment during World War II and even rabid anti-Semitism do not make Arabs co-conspirators in the genocide that took place thousands of miles from the Middle East. Arab Holocaust denial has developed out of the dynamics of the Arab-Israeli conflict in general and the dispossession of the Palestinians in particular. The Holocaust, however central in Israeli collective memory, occurred in another place and was the work of other hands. Its stain upon humanity is dark and deep enough; it must not be allowed to poison the soil upon which peace between Israel and a Palestinian state may finally be attained. Gilbert Achcar has not succeeded at overcoming the “Arab-Israeli war of narratives,” but he has taken an important step towards reframing it.

Suggested Reading

Waiting for Passover—and Revolution—in Venezuela

For the 6,000 Jews left in Venezuela, life is precarious. "...All three of us have been kidnapped," a chillingly relaxed young man at Hebraica Jewish Community Center tells me.

The Way We Live Now

One uncanny thing about this moment is that no one has yet put the experience we are all having—collectively yet separately, sometimes on Zoom—into articulate words.

How Many Tears?

Which played a larger role in Jewish migrations: oppression or economics?

A Foreign Song I Learned in Utah

Despite all of Bob Dylan’s subterfuges, disguises, and costume changes, he really was a child of the American heartland. Winning the Nobel Prize might actually be his most Jewish achievement.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In