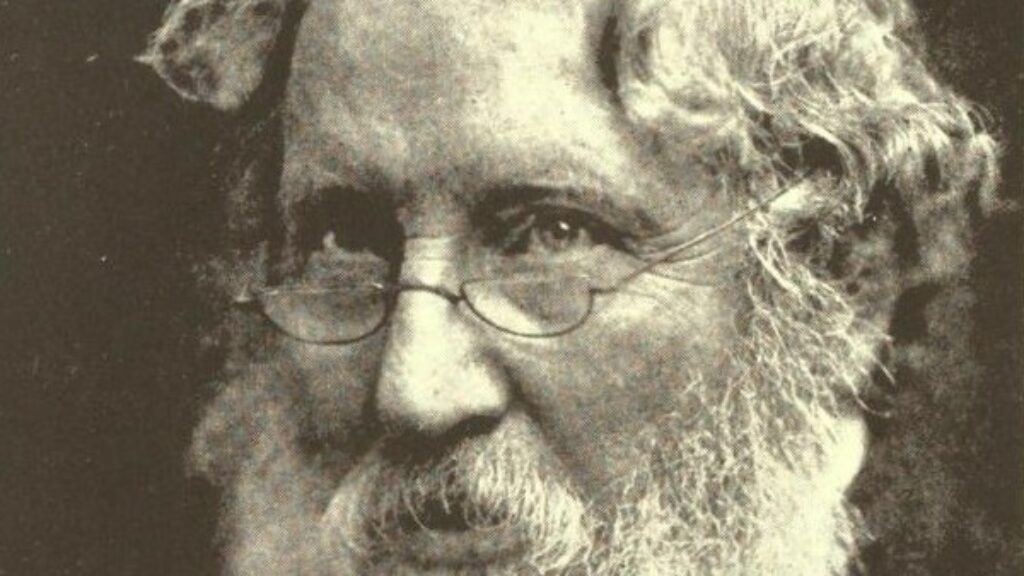

The Jewish Turn of Norman Podhoretz

Norman Podhoretz is a great American success story—a poor Jewish kid from the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, feisty and brilliant from a young age, lucky enough to find an eccentric high school

teacher who introduced him to the world of ideas, then off to Columbia University, where he was quickly on his way to being one of the leading literary critics of his generation. Which he became, at least for a while. Which he was, sort of.

Men of letters often care more for letters than for life; words, for them, are everything. But words were not enough for Podhoretz. For all his ideological twists and turns—ultimately leading him to become one of the most influential figures of neoconservatism from the 1970s to the present—he discovered early on that the craft of writing mattered most as the carrier of clear arguments about the best life, the best society, and the truths of being human. Podhoretz craved success, and fame, and fortune. But he needed to smash idols even more.

This is a story Podhoretz has told with great candor and verve in Making It, his autobiographical polemic (a genre he more or less invented), and its successors Breaking Ranks, Ex-Friends, and My Love Affair with America. But Thomas Jeffers’ new book is the first full biographical study of Podhoretz. When it appeared last year, it received, as one would expect, a great deal of critical attention and also generated some political ire. But few critics have focused on it as the story of a distinctively Jewish life. It is a fascinating story, and Jeffers tells it ably if not brilliantly, providing the narrative tale if not always the most probing analysis of who Podhoretz is as a thinker, a political force, and a Jew.

Norman Podhoretz was born in 1930 to immigrant parents. His Yiddish—speaking father was “a nonobservant New World Jew who at the same time treasured the Hebraic tradition.” But Jeffers only spends a few pages on his family and childhood before moving quickly on to the Columbia classroom of Lionel Trilling, where Podhoretz became the star student of that era’s greatest critic. To placate his father, Podhoretz also studied Jewish history and texts at the Jewish Theological Seminary, a parochial place (as he saw it) without the fascinating charm and power of the ancients and moderns that beckoned him from beyond its cloistered walls. Then to Cambridge University, where he discovered what it meant to be an American, not just a Jew from Brownsville, and that even in the world of high culture there were fault lines just as sharp and deep as among the ethnic gangs of the old neighborhood. So he returned home, PhD-less, served an early-1950s stint in the army, and then “broke in” to the New York literary-

intellectual circles of his day—the “family,” as it famously came to be called—with reviews of Bernard Malamud, Saul Bellow, Simone de Beauvoir, Faulkner, Camus, and other rising and dying literary giants of the mid-century.

His first real job was as a young editor at Commentary—by then, in the mid-1950s, a leading voice of the high-culture, anti-Communist left, with Jewish interests but no defined vision of what a flourishing Jewish future in America (or Israel) should really look like. It was also a magazine in chaos—with its brilliant but troubled editor Elliot Cohen in and out of the psychiatric ward, only to take his own life in 1959. It was then, at age 30, that Podhoretz became editor-in-chief of the magazine that he would shape for the next 35 years and that would help determine the direction of American political, cultural, and intellectual life.

In those years leading to his editorship of Commentary, Podhoretz was writing up a storm and having, as Jeffers narrates, his own adventures in sex and celebrity, hanging out with Norman Mailer and other famous (and now famously ex-) friends. But he was never quite so radical, or so deviant, or so insane as the other Norman, not to mention the Beat poets and other literary lights who felt the sting of his critical dismissal. Plus, he had the great fortune to know Midge Decter, a divorcée with two young children, whom he wed in 1956. Podhoretz quickly had to become an adult, responsible for and to others. But he was also, even once married, still a radical mind, seeing the left-wing revolt against mainstream, bourgeois America as the key to both a great magazine and a national revolution of the spirit—probably in that order of priority.

Podhoretz’s account of this period in Making It was an effort to describe, in bold and limpid first-person prose, the meaning of success in America—the hunger for it, the rivalries that emerged in its pursuit, and the falsehoods that surround all those who claim not to be after it at all. But what makes the book an enduring work of literature is the descriptive genius of its author, whose lacerating eye and beautiful pen brought to life such varied topics as Jewish life, the nature of writing, the experience of being in the army, the character of liberal education, and the illusions of the American individual. Some readers will be fascinated most by the personalities-the luminaries of the New York intellectual scene, warts (or worse) and all. Others will be enchanted by the politics-and especially the romance with radicalism (short-lived as it would prove to be). But if one is looking to understand the author himself, and who he would eventually become,

the Jewish self-analysis—one might even say self-obsession—of the book is the place to look.

Here is his description of the Judaism of his father:

He was sympathetic to socialism but not a socialist; he was a Zionist, but not a passionate one; Yiddish remained his first language, but he was not a Yiddishist. He was, in short, a Jewish survivalist, unclassifiable and eclectic, tolerant of any modality of Jewish existence so long as it remained identifiably and self-consciously Jewish, and outraged by any species of Jewish assimilationism, whether overt or concealed . . . The point was to be a Jew, and the way to be a Jew was to get a Jewish education; never mind about definitions, ideologies, justifications.

Later, and by stark contrast, he describes the (anti-)Judaism of the early generation of Jews within “the family”:

But if not America, then to what did the family think it belonged? Not, certainly, to the Jewish people. They, of course, were universal men. As good Marxists, they regarded Zionism as yet another form of bourgeois nationalism, they considered the “Jewish question” a minor aspect of the crisis in capitalism, and they looked forward with great equanimity to the disappearance under socialism of the Jews as a distinct people, seeing no point in their survival… So little point did the family see in Jewish survival that the threat being posed even at that moment by Hitler to the actual physical survival of Jewish men, women, and children did not, to judge by the files of Partisan Review, seem a matter of urgent concern.

Even while the inward-looking world of the Seminary would never be enough for Podhoretz, he already harbored, in the 1960s, a nascent contempt for the Jewish self-hatred of those first-generation intellectuals, as well as an unwillingness, even then, to settle for the watered-down Judaism of second-generation Jewish literary chic. At the time, Podhoretz had little of a positive Jewish nature to offer the world-which was the gist of a famous attack on Podhoretz by the theologian Michael Wyschogrod. But eventually, he would need to find a different way—an American version of Jewish pride and a Jewish version of grand history, that would honor his father’s survivalism but go much farther, and that would embarrass the anti-Jewish and pseudo-Jewish Jewish intellectuals, armed with the truths and poetry and political triumphs of his own people.

It was around then, as the 1970s dawned, that Podhoretz had a revelatory experience at his country house in upstate New York, an experience upon which Jeffers dwells at some length and that marked the end of his radical politics and Jewish ambivalence. It is also a story that Podhoretz himself has never written about. Suffering from a mix of writer’s block and an existential hang-over from the 1960s that he did not yet fully understand, the now 40-year-old Podhoretz had a vision that Judaism was true, that “all modalities of human existence” are subject to a moral law, and that we are called to “choose life” in the face of our own mortality. As he would recall in a letter a few months later:

Alas, so sunk in sin am I that I can scarcely even remember “it” [his vision] any longer. That, too, was part of the discovery—that as soon as the truth is revealed it is forgotten, which is why Jews are commanded to daven (usually translated as “pray,” but meaning in my view something closer to “recite” or “rehearse” or “remind” than to supplication and praise). I quote from memory from the Bible: “Thou shalt teach them [the commandments] to thy sons and thou shalt speak of them as thou liest down and as thou risest up and as thou goest forth on the road.” This is to make sure that the revelation of how one is to live . . . won’t slip away as it constantly threatens to do. It slips away leaving the mind utterly blank; at other times it slips away into over-complication and the falsities of the abstruse. Why does it slip away? Because to know it, to remember it, to hold onto it firmly (one is told to hold onto the Torah, the law, the commandments, as to the Tree of Life) is to hold firmly to the awareness of one’s own mortality.

A new Podhoretz gradually emerged—still the same brilliant mind, the same sharp pen, the same personality in search of greatness and renown. But the editor had a new purpose, and a new inspiration. Seeing, as he now saw them, the destructive idols of the cultural, political, and anti-theological Left, he would devote the next four decades to three great ideological wars—for American and Israeli strength in the face of appeasement at home and deadly enemies abroad; for the imperfect but real prosperity of freedom against the poverty and coercion of communist and liberal utopianism; and for moral responsibility and family life against the destructive culture of sexual nihilism. In fighting these fights, he would become the confidant, educator, and irritator of professors and presidents, making many new friends and impressive enemies along the way. In all these fights, Podhoretz believed that he had Judaism on his side and that he was on the side of the Jews.

He also became a passionate American Zionist—arguably the preeminent political Zionist in America. He saw early on that the anti-Zionism that emerged in the wake of the Six-Day War of 1967, with its relentless attacks on every Israeli effort to defend itself against its enemies, was so irrational, so unjust, and so committed to judging the Jewish state according to pernicious double standards, that it was really a deadly new form of left-wing anti-Semitism. He saw early that efforts to appease Israel’s enemies would only invite further destruction and embolden those who sought to eliminate Israel from the face of the earth. And he saw, perhaps late but vividly, that the supposed tension between Jewish particularity and cultural universalism was a false dichotomy: Jews really are the chosen people; their persistence in history is empirical evidence of their grand purpose; and their teachings, carried forth in the Hebrew Bible, are the truest account of human nature that mortals will ever possess. As Podhoretz wrote in the conclusion of his book on the Hebrew prophets ten years ago:

What we have . . . in the classical prophets is a running response to the social, political, and historical realities of the world around them. Such realities can be as large and momentous as the clash of empires in which the fate of the nation is at stake. Or they can be as trivial as an improper deal between anonymous traders in the marketplace . . . This facet or aspect of classical prophecy can also be understood as a derivative instance—an epiphenomenon, if you like—of the “scandal of particularity.” For just as, in the view of the prophets, the only road to the one God of all is through the revelation He mysteriously granted to one small and insignificant people, so does the apprehension of universal or “higher” truths depend upon a grasp of and an immersion in the realm of the mundane and in the dailiness of life.

At a dinner in 1985 honoring Podhoretz for 25 years of editing Commentary, following toasts and tributes by Henry Kissinger, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, Benjamin Netanyahu, Jean Kirkpatrick, and George Shultz, the honoree himself rose to respond, and jokingly complained that nobody praised him for his humility. It is a joke he would have occasion to repeat over the ensuing decades as well. And if there is a Podhoretzian flaw—perhaps a necessary flaw, driving him forward all these years—it is his naked ambition to be a great figure, and his confident belief that he is one. And so he is, by the normal standards of history. But I also wonder whether this man of visions, who understands so much of his life’s deepest purpose in Jewish terms, is probing enough about the ultimate limits of his own Jewish vision.

He is certainly deeply aware of the Jewish crisis in North America—assimilation through intermarriage combined with a piety toward modern liberalism that undercuts the moral vision of the Jewish tradition, especially on matters of sexual and family life. But just what Jewish fidelity in America requires “in the realm of the mundane and in the dailiness of life” is a deep question that Podhoretz has never really addressed. He admires the Jewish way of life but never articulates, or demonstrates, what a viable, traditional, self-confident diaspora Judaism should look like. For all of his trenchant writings on Jews and Judaism, it is here that one is left wishing for more.

Suggested Reading

Kol Nidre with Dragons

One of the most spectacular books of medieval Ashkenaz, the Leipzig Mahzor, contains a stunning illumination for the opening of Yom Kippur.

The Inheritance of Jacob: A Rejoinder

Abraham Socher closes out his exchange with Tal Keinan, author of God Is in the Crowd with a rejoinder.

Jeremiah, Ben-Gurion, and Hillel Halkin

In one of David Ben-Gurion’s last addresses on the Bible, an essay entitled “The Monarchy and the Prophethood” delivered in October, 1968, the old, former prime minister meditated on Yehuda…

Godly Guardrails and Secular Assumptions

Ilana M. Horwitz convincingly argues that religious students are high achievers. But what’s the special sauce that makes it so, and who gets to decide what counts as an achievement?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In