Kol Nidre with Dragons

This fall you might head into services with a mahzor in hand, but in the Middle Ages most Jews prayed from memory and by responding to the refrains of their hazzan (prayer leader). Mahzors were produced not for ordinary Jews but specifically for those leading the congregation in worship and typically contained the full cycle of special prayers and piyyutim (liturgical poems) for the entire year (the Hebrew word “mahzor” literally means “cycle”). I say “special prayers” because mahzors did not include regular prayers like the Shema and the Amida, which, it was assumed, everyone knew by heart.

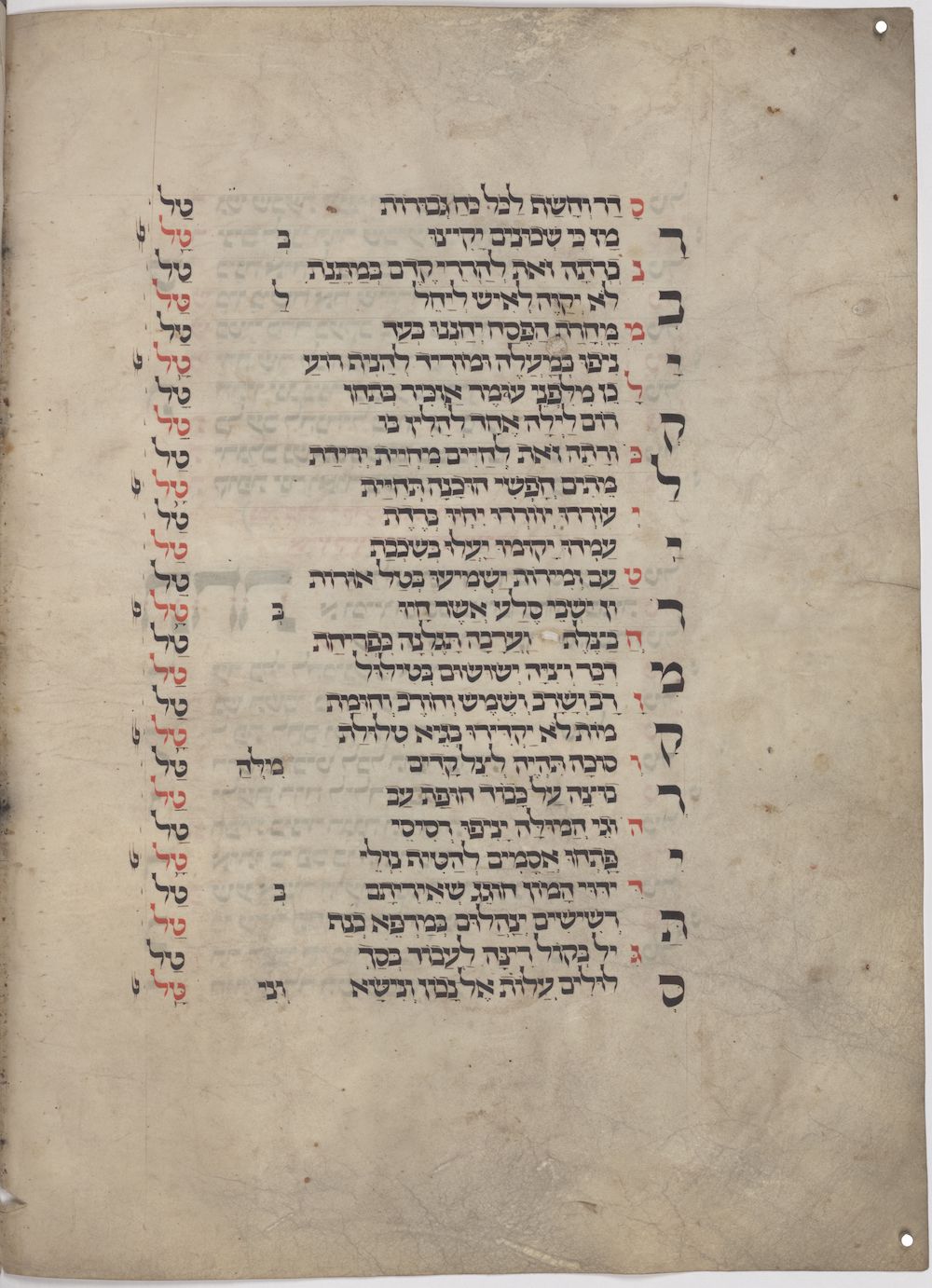

Nor did these mahzors look anything like the prayer books we might be holding in our hands this September. They tended to be massive in size and usually came in two separate volumes (one for the holidays from Rosh Hashanah through Hanukkah, the other for special Sabbaths before Passover through Tisha b’Av). Their oversized folio pages were carefully laid out with large Gothic-looking Hebrew letters written in black and red ink. In keeping with the style of Christian books of that era, pages were often lavishly decorated with gold-leaf letters, arched gates, and borders filled with creeping vegetation and teeming with cavorting beasts, even human figures. In many cases, the meaning of these decorations is difficult to ascertain.

While medieval mahzors were generally commissioned and owned by wealthy individuals, the books themselves were fundamentally communal. The mahzor’s nusach, or liturgical rite, was specific to the community for which the book was produced, and its illustrations often pictured the world of the mahzor’s community. The members of the community could literally see themselves in the pages of their prayer book.

These Ashkenazi mahzors are among the most spectacular achievements of premodern Jewish culture. The famous Leipzig Mahzor—so-called because it has been in the library of the University of Leipzig for the last two-and-one-half centuries—is a particularly astonishing example. It was originally produced in the 13th century for the community of Worms. (Located on the west bank of the Rhine, Worms was one of the great centers of medieval Ashkenazi Judaism, home to, among others, the great biblical and talmudic commentator Rashi and the Ashkenazi pietist Eleazer of Worms, also known as Ha-rokei’ach “the Perfumer.”) The Leipzig Mahzor served the Jewish community of Worms for almost four hundred years. In the wake of violent persecutions, the mahzor accompanied its owner to eastern Galicia (then Poland, now western Ukraine), as indicated by a number of marginal annotations. In the mid-17th century, the mahzor appears to have made its way back to Germany, possibly after the Khmelnytsky massacres in Poland. In 1746, the two-volume set was acquired by the University of Leipzig—apparently one of the library’s first acquisitions—where it has resided ever since. Both its “tremendous weight and its highest artistic style” (as noted in the library catalogue) had sufficiently impressed the university’s chief librarian, a Christian scholar who knew Hebrew along with many other ancient and modern languages, that he was willing to pay a very large sum (26 reichstalers) to acquire the two volumes.

When, midcareer, I first became interested in Jewish books—the physical artifacts, the books Jews have actually held in their hands—I received valuable (and, in retrospect, obvious) advice from an eminent senior scholar in the field. “Go to libraries,” he told me. “Look at manuscripts. Touch the pages. Sniff the parchment. Sometimes you can smell the cow or sheep. Even books can have life in them.” How right he proved to be.

In the summer of 1998, I journeyed to Leipzig. At the time, the university library was being renovated, so the director set me up at a large table in an office, and as the librarians bustled around me doing their cataloguing, I marveled at this eight-hundred-year-old prayer book, the likes of which I had never imagined, let alone studied. My mentor was right: The book really did have a life in it. Books are like people; they have lives. And Jewish books, I realized, are like Jews, and their lives are Jewish lives.

The Leipzig Mahzor’s wanderings, inscribed in physical markings on its pages, were one part of its life as a Jewish book. But there were many other signs. The two volumes were written by different scribes—Menachem and Isaac—each of whom left his name in the volume either by flagging the initial letters in acrostics or by sometimes highlighting his name when it appeared in the texts of prayers. While the scribes were Jews, the mahzor’s artist was almost certainly a Christian, as suggested by the awkward Hebrew letters in some of his drawings. (Christian artists were often hired by the Jewish patrons or scribes to illustrate their books but always under their supervision and direction.)

Some of the mahzor’s illustrations were added in the early 14th century. But even more remarkably, in the course of its wanderings, the two volumes of the Leipzig Mahzor had been rebound, and, in the process, some of the pages were shuffled. One volume was now bound upside down. Inscriptions on end pages carried names of past owners, and other annotations marked ritual changes made by prayer leaders in the various locales through which the mahzor had passed, where the Worms rite had been adapted to those of other communities.

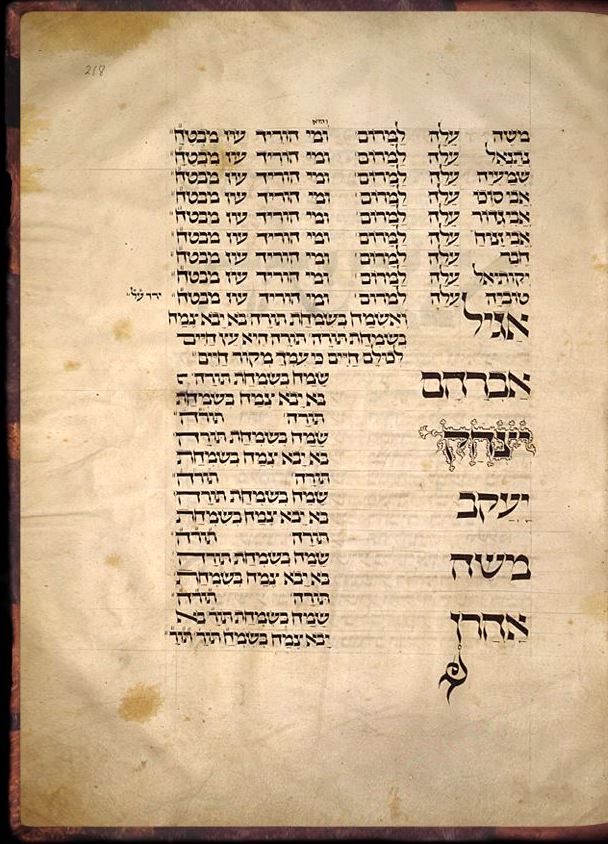

Everything about the mahzor was visually astonishing; even the unilluminated pages had been crafted with great care. The lines of the piyyutim, sometimes even individual words, were written in alternating colors and in different, arresting patterns. Letters were set off at the beginnings and ends of lines to form borders in embroidery-like columns.

But of course, the most striking thing of all was the illustrations. The Leipzig Mahzor’s most famous illustration shows Samson wrestling with a young lion (Judges 14). Found on the opening page of the first volume, it is quite different from the early pictures that were part of the original mahzor and is probably among those that were added in the early 14th century. Exactly what the illustration is doing on the page is unclear; the text written around it in tiny Hebrew script is Ezekiel 1, the haftarah (prophetic reading) for the first day of Shavuot. Perhaps the swirling, intertwined figures of Samson and the lion reminded the patron of Ezekiel’s four-headed beast.

My favorite image, however, appears on the opening page for Kol Nidre, probably the most famous piece in the entire Jewish liturgy (partly because it was immortalized in The Jazz Singer), even though it isn’t really a prayer at all. It is a ritualized court proceeding that annuls all of our vows—a mock legal ceremony that apparently serves as one more way of asking God to forgive our transgressions and failures. Its origins are obscure, but what is most powerful about Kol Nidre is not its legal terminology or its words (Aramaic, by the way, which was probably unintelligible to most Jews in the Middle Ages) but the haunting melody of the chant, the drama created as it builds from an inaudible murmur to a loud and insistent pleading.

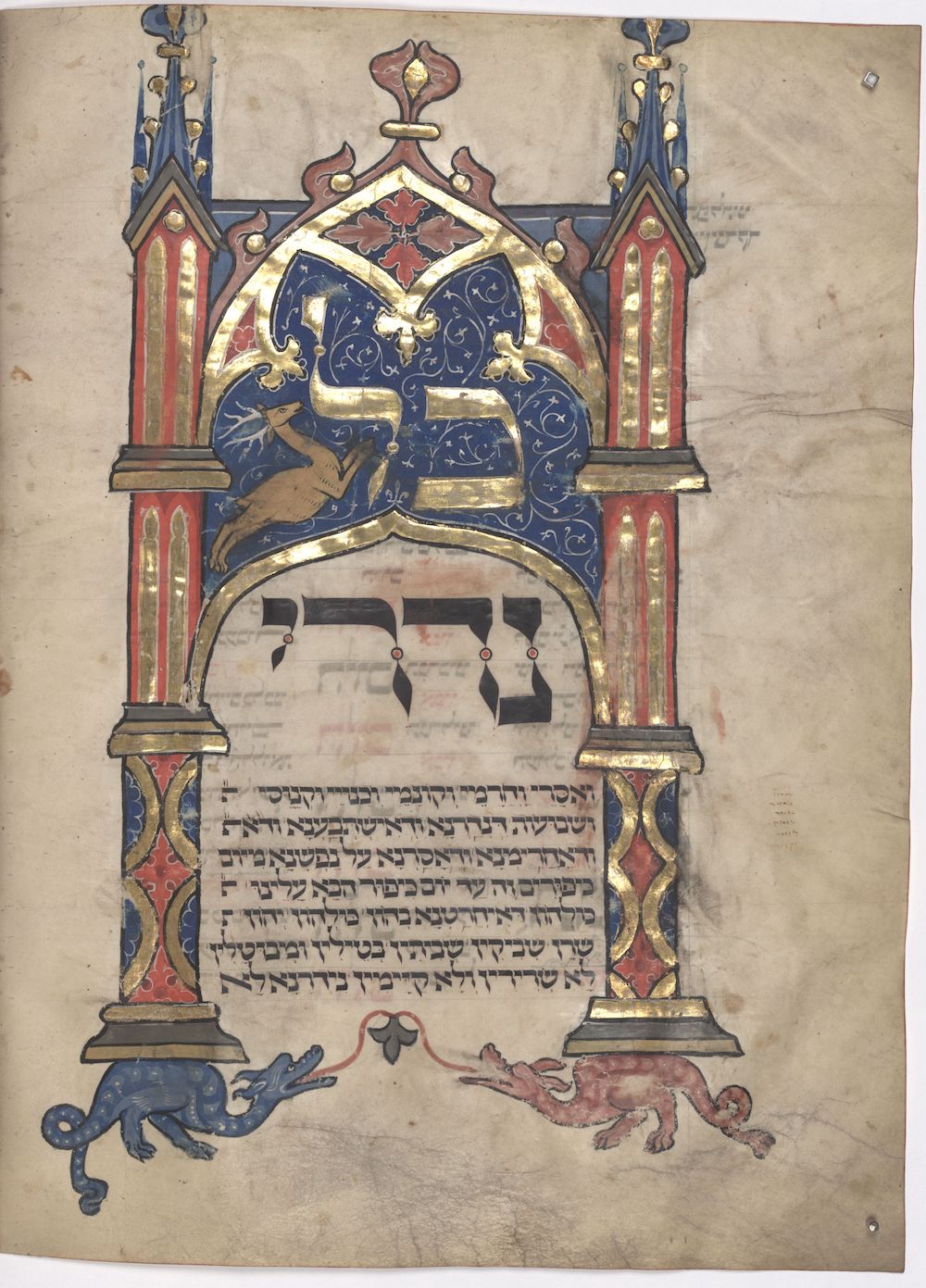

The image on the Kol Nidre page of the Leipzig Mahzor, which takes up far more space than the prayer itself, matches the liturgical atmosphere. A Romanesque gate, outlined in gold leaf, with an elaborate flower-like crown and soaring sculptured towers, fills almost the entire page. (The fact that the tops of the two towers are cut off is not a fault of the reproduction. When books were rebound in the Middle Ages, bookbinders often cut down pages in order to make their size uniform. Such, alas, seems to have been the fate of this page.) Within the tympanum (decorative lintel) of the gate, the word “kol” (all) is written in giant gold-leaf letters against a delicate blue background, and beneath it, hovering in the air in giant black letters, “nidre” (vows). Below that, within the gate’s space, the rest of the Aramaic prayer is written in a smaller script.

The two heavy columns supporting the gate rest on the backs of two fearsome dragons, their tongues meeting in the middle somewhat playfully in a graceful upside-down fleur-de-lis, thereby completing the frame surrounding the entire prayer. These dragons are partly decorative, but they also probably represent forces of evil—powers of darkness, perhaps, or even our distracting thoughts. The Hebrew “drakon” was also the word for “snake.” Dragons (snakes) frequently appear in Christian art of the period as well, typically symbolizing Satanic forces. In the words of Jewish art historian Marc Michael Epstein, they are “the apparently capricious and destructive forces of fate” that “seem to gnaw at the underpinnings of faith.”

But how do the dragons, representing something sinister, function on this page? Are the columns and the text of Kol Nidre itself somehow suppressing them or holding them at bay? Or have these threatening “forces of fate” already been disarmed by the power of prayer and repentance and incorporated into God’s world, where they now serve as the very foundations of the cosmos, whose columns they support on their backs?

Medieval prayer books often used a decorated gate—in Hebrew, sha’ar (the same word we use today for a title page)—to mark the beginning of an important prayer or section. But a gate is also an invitation, an opening for readers to enter. This gate is a supremely appropriate illustration for Kol Nidre precisely because it is an invitation to enter within.

The illustration’s most striking detail, which is hardly noticeable at first, is the spirited stag leaping within the filigreed blue panel inside the tympanum, almost touching the leg of the lamed, the final letter of the opening word “kol.” What is this deer with its great antlers doing in the picture, leaping upwards? Whom might it symbolize? The people of Israel? The community gathered together that evening in the synagogue to pray? Perhaps even the soul of the worshipper? “Like a hind [that is, a deer] crying for water, my soul cries for You, O God,” the psalmist tells us. Follow me, the illustration beckons. What more fitting image could usher in 25 hours of intense reflection and prayer?

Looking for something else to read? We recommend Adam Kirsch’s review of David Stern’s The Jewish Bible: A Material History or our interview with David Stern about the history of the Jewish book. You might also enjoy this other stunning example of a medieval mahzor.

Suggested Reading

Stemming the Yuletide

As the Yuletide rolls in, one finds oneself yearning for some Hanukkah pop with a little more depth than Adam Sandler’s Hanukkah song.

Brotherhood

How did the world's most antisemitic play become a symbol of positive Christian-Jewish relations? Karma Ben Johanan's new book explores an evolving dynamic.

Touch: Passover under COVID-19

It makes sense not to touch during a pandemic. But did we truly touch before it and will we after?

America’s Jewish Bridegroom

Horace Kallen can be found in the ill-starred pantheon of prolific writers known for only one thing: one novel, one sonnet, one treatise, or, in his case, one idea. That idea is “cultural pluralism.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In