The Zionavar Tapestry

The Canadian fantasy writer Guy Gavriel Kay recently published his 14th novel. A Brightness Long Ago is a romance set in a 15th-century Italy that has been lightly altered with name changes and touches of magic. Yet Kay would be assured a place in the history of fantasy literature even if he had never written a word. That’s because, when he was 20, J. R. R. Tolkien’s son (whose wife was a friend of the Kay family) asked him to help edit his late father’s manuscripts, resulting in the 1977 publication of Tolkien’s mythological epic, The Silmarillion.

Kay was born in Saskatchewan in 1954. His father, a doctor, was a Jewish immigrant from Poland, and his mother was an artist. An undergraduate at the University of Manitoba when his work for the Tolkien estate carried him off to England for a year, Kay subsequently returned to Canada and earned a law degree from the University of Toronto. His own career as a fantasy writer was launched a few years later with the publication of the Fionavar Tapestry, a trilogy of novels consisting of The Summer Tree (1984), The Wandering Fire (1986), and The Darkest Road (1986).

In the trilogy, five university students travel to a medievalesque fantasy world and participate in an epic battle against an evil god. The first novel opens with the students attending a lecture at the University of Toronto given by a famous scholar of Celtic studies. The scholar turns out to be a wizard who magically sweeps them off to the land of Fionavar, much as Kay was swept off to Oxford by the legacy of the legendary professor Tolkien.

Tolkien’s influence is seen throughout the trilogy. Kay’s imports include Tolkien’s tragic dwarves, ancient elves, evil orcs, ent-like giants, a traitorous wizard, and a dark lord whose very name, Rakoth Maugrim, echoes the name of the evil foe in The Silmarillion, Morgoth Bauglir. Kay’s Dalrei, an equestrian, plains-dwelling people, resemble Tolkien’s Riders of Rohan—though I wonder if the name is also a wink at Del Rey, the fantasy imprint that launched in 1977 with the publication of Terry Brooks’s bestselling Tolkien knock-off, The Sword of Shannara.

Tolkien’s influence dominated fantasy literature written in the late 1970s and 1980s, when his Lord of the Rings trilogy had for many become definitive of the genre itself. What is unique about the Fionavar Tapestry is the pathos it generates by wrestling so openly and pervasively with this influence. Kay’s trilogy constantly poses this question: Is it possible to write fantasy in the shadow of Tolkien? In fact, it is hard not to see the trilogy’s epic battle with Rakoth Maugrim as a figuration of Kay’s battle with Tolkien. The Fionavar books overflow with images of influence and the struggle against it: multiple instances of sons rebelling against fathers, heroes trying to rewrite their own stories, and discourses about tapestries and whether one is free to undo and reweave what has already been woven.

Even the original plot devices in the trilogy relate to this theme. In one memorable instance, Kay offers a macabre rewriting of perhaps the central myth in Tolkien’s fiction—that of the twilight of the elves, who pass from Middle Earth over the sea in ships, leaving history to mortal men. In Fionavar, the elves have been doing this for centuries—or so they thought. Kay’s protagonists discover that, all this time, a sea monster has been gobbling up the migrating elves before they ever reach their destination. This episode is a bold attack on Tolkien and his beloved elves, yet it also expresses anxiety about the master’s influence and Kay’s originality since Kay’s monster also absorbs and mimics the voices of its victims.

The most striking feature of the trilogy is the fantasy mash-up brought about when King Arthur, Lancelot, and Guinevere are imported into Fionavar in order to defeat Rakoth Maugrim. Kay was not the only fantasy writer of the time to make use of Arthurian elements or, for that matter, of the Celtic mythology that also runs through much of the trilogy. Yet by enlisting Arthur and company against Rakoth Maugrim, Kay evades Tolkien’s impossible influence by accepting the deformations of a different one. This is a sacrifice play, mirrored in the books by the many instances of characters sacrificing or mutilating themselves in order to achieve some victory.

One such sacrifice is Kevin Laine, the trilogy’s only Jewish character—and the only one of the five students who does not survive. Is there a connection? Unlike his friends, Kevin is not transformed by his arrival in Fionavar. His companions become heroic: One becomes a mighty warrior, another a mystic priestess. One even discovers that she is the reincarnation of Guinevere. But not Kevin, who remains a talented law student if rather useless in a war against a god. “He had nothing to contribute,” writes Kay. “What he seemed to be, here in Fionavar, was utterly impotent.” His role is mainly to witness the transformations and struggles of his friends—a clear figure of the author within the work.

Except that in book two, Kevin does finally take on a heroic role: He sacrifices himself to a love goddess on Midsummer Eve, an act that breaks the spell of permanent winter being used against Fionavar. Earlier on, we are told that Kevin’s most distinctive characteristic is his intense erotic sensitivity—ironic given his narrative “impotence.” Sex is, for Kevin, “a blind, convulsive reaching back into a falling dark. . . . It took away his very name.” He therefore intuits that he is the incarnation of Fionavar’s mythic hero Liadon and is meant to enter the goddess’s cave and leap into the chasm within. In a paroxysm of desire, he does so—albeit with a final note of Jewish guilt at the sorrow his death will cause his widower father (“Abba, he thought, incongruously”).

This episode too is not without echoes of Tolkien, since Gandalf also sacrifices himself by falling into a chasm in the middle of Lord of the Rings. Yet Kay links Kevin’s death more directly to a different story, the Greek myth of Adonis. Like Adonis (or Liadon, as he is known in Fionavar), Kevin is wounded by a boar during a hunt earlier in the tale, dies in the arms of a love goddess, and has his death memorialized by red, springtime flowers. Nonetheless, as we will see, though killed off midway through the Fionavar trilogy, Kevin returns perennially in Kay’s subsequent novels, an ambivalently Jewish figure for Kay’s ongoing ambivalence about fantasy, myth, and desire.

After the Fionavar trilogy, Kay turned from epic fantasy to historical fantasies such as A Brightness Long Ago. These novels are based on real-world settings but with the names changed, events altered, and a patina of magic laid on. His next several novels were set in versions of Renaissance Italy, medieval Provence, medieval Andalusia, the Byzantine Empire in late antiquity, and 9th-century England. Rather than contending with the influence of Tolkien or Arthurian romance, he accepted the more impersonal yoke of history and wrote his story around the edges.

Kay makes use of a good deal of Jewish history in some of these novels, especially The Lions of Al-Rassan (1995), which is based on 11th– and 12th-century Spain and focuses on the interaction among Jews, Muslims, and Christians. He cites the great historian S. D. Goitein in his acknowledgments, and, in the course of the novel, he quotes poems from the corpus of medieval Hebrew poetry. Yet Kay’s fantasy religions differ in that they worship celestial bodies. The Kindath (Jews) worship the two moons that orbit this world, the Asharites (Muslims) worship the stars, and the Jaddites (Christians) worship the sun. This largely contentless scheme works for a novel that tends to view religious differences as fanaticism or hypocrisy, an obstacle to be overcome by more universal virtues of refinement, education, and compassion.

Kay further detaches his world from the historical by making women far more emancipated than were their real 12th-century counterparts. Jehane, the Kindath protagonist, is a freewheeling doctor, a kind of female Maimonides turned adventurer who pursues zesty romances with both Jaddite and Asharite men. Kay’s novel renews a tradition, dating back to 19th-century Germany and England, of historical romances of Moorish Spain featuring noble Jewesses, some of which were written by Jewish authors such as Grace Aguilar and Ludwig Philippson, others by philo-Semitic writers such as Sir Walter Scott. Like these precursors, Kay emphasizes the values of cosmopolitan tolerance against religious fanaticism and exclusion.

One notices that, unlike historical Jews, Kay’s Kindath have no concept of a Zion from which they came and to which they might one day return (or even visit as pilgrims). They are defined by their status as eternal wanderers (“we who call ourselves the Wanderers are the symbol of the life of all mankind”). So, while Kay draws from many of the rich, diasporic aspects of Iberian Jewish culture, a figure such as Judah Halevi, the great Hebrew poet of medieval Spain who yearned for Zion, is not included. Tellingly, the center of Kindath culture is seemingly modeled on Ottoman Salonica, not Jerusalem.

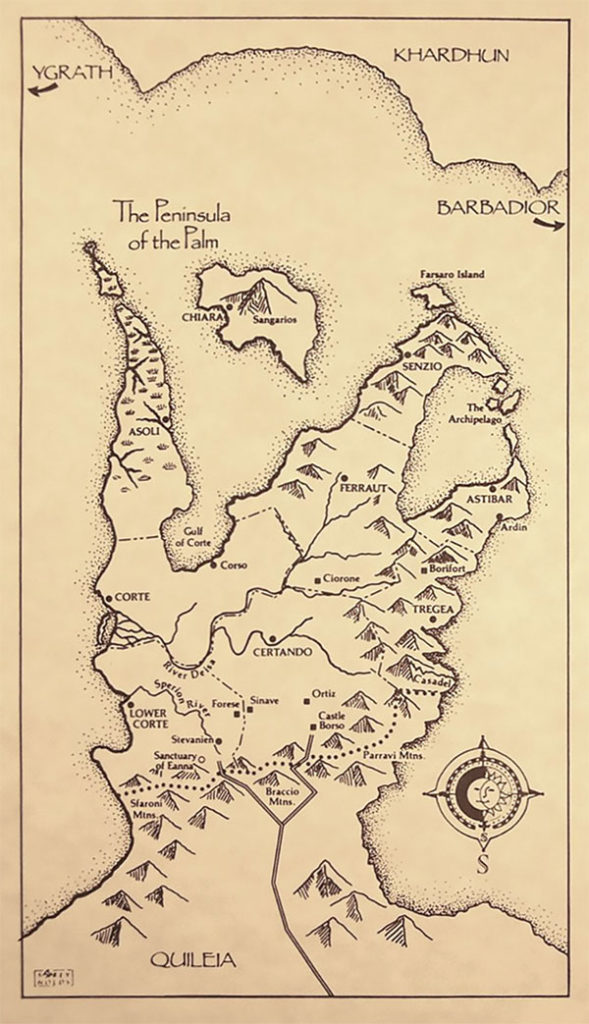

On the other hand, his earlier novel Tigana (1990) is haunted by a Zionism that never becomes explicit. Tigana is a powerful story about revenge, politicide, and the lengths people will go to in order to suppress or hold on to their memories. The setting resembles fractious 16th-century Italy, though in this case one of the conquerors of the novel’s peninsula is a powerful sorcerer. In retaliation for the death of his son in battle against the rebellious republic of Tigana, this despot uses his magic not only to crush the population’s resistance but to eradicate its very name and memory. Only the survivors of the rebellion can recall their country. A spell prevents anyone else from believing that there ever was such a place as Tigana, which has been renamed after a rival state. “He made it as if we had never been,” says one of Tigana’s exiles, “Our deeds, our history, our very name.”

In his afterword to the 10th-anniversary edition of the novel, Kay cites a series of historical events that he says directly inspired or parallel his story. He mentions the Soviets crushing the Prague Spring, Communist whitewashing of undesirables from their histories and photographs, the colonization of the Irish by the English, and the attempt to preserve languages by nationalists in Wales and Quebec.

This is all intriguing, but might there be another example of a people driven into exile who struggled against seemingly insurmountable odds to maintain their cultural memory and eventually restore their nation’s sovereignty? “Tigana, let my memory of you be like a blade in my soul,” proclaims one of the exiles as his most sacred oath. Might this have been inspired by a different exilic vow: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, let my right hand lose its cunning”?

Tigana, one of its partisans tells us, was renamed by its imperial conqueror “after the bitterest of our ancient enemies among the provinces.” Does this not call to mind—despite its absence from Kay’s afterword—the Roman renaming of conquered Judea as “Palestine,” after the ancient Philistines? It may be going too far to suggest that Dianora, a woman from Tigana who winds up falling in love with her people’s enemy, has a name that sounds, appropriately, like the term for the dispersion of the Jews. But it does seem less than coincidental that the name of Devin Bar Garin, another of the Tiganans who wakens to his country’s erased history, recalls the first prime minister of Israel.

Much as the magic spell forces the people of Tigana to remain silent about their identity, Kay remains silent about the concern with Jewish memory and identity that informs the thematic substratum of the novel, which might otherwise be dubbed Zionavar. Tigana, as Kay explains in the afterword, demonstrates both “the necessity of [memory], in cultural terms, and the dangers that come when it is too intense,” a formulation that describes the ambivalence of many a Western Jew toward Judaism and the Jewish state. At one point in the novel, the Tiganan exiles discuss their parents’ unwillingness to claim their provenance openly, and they do so in terms that recall both Holocaust survivors and Jewish responses to anti-Semitism:

“Few of the survivors spoke of those days,” Baerd said

“Neither of my parents did,” said Catriana awkwardly. “They took us as far away as they could, to a fishing village here in Astibar down the coast from Ardin, and never spoke a word of any of this.”

“To shield you,” Alessan said gently. His palm was still touching Devin’s. It was smaller than Baerd’s. “A great many of the parents who managed to survive fled so that their children might have a chance at a life unmarred by the oppression and the stigma that bore down—that still bear down—

upon Tigana. Or Lower Corte as we must name it now.”“They ran away,” said Devin stubbornly. He felt cheated, deprived, betrayed.

Alessan shook his head. “Devin, think. Don’t judge yet: think. Do you really imagine you learned that tune by chance? Your father chose not to burden you or your brothers with the danger of your heritage, but he set a stamp upon you—a tune, wordless for safety—and he sent you out into the world with something that would reveal you, unmistakably, to anyone from Tigana, but to no one else. I do not think it was chance. . . .”

As if all this subtext were not enough, Devin, whose name, in addition to its similarity to David Ben-Gurion, rhymes with Fionavar’s Kevin, has a dream that links him to the earlier Jewish character.

In the dream, he sees a mythic figure called Adaon (a version of Liadon from the earlier Fionavar episode). Like Kevin/Liadon, Adaon also meets his death at female hands in a cyclical ritual, though here Kay makes use of the Greek story of the maenads, the wild women followers of Dionysus who rend men apart in their savage ecstasy. Adaon is a “dying god” who each year must be “torn apart in frenzy and in flowing blood by his priestesses,” which allows the agricultural cycle to resume in the spring when he returns to life and couples with two goddesses, “his mother and his bride, his sister and his daughter,” a tracing of the Adonis myth back to its Sumerian roots. Adaon, in Devin’s dream, stands at a “high chasm”—like Kevin at his sacrifice in Fionavar—waiting for the women who will bring his ritual death. Kevin’s erotic self-sacrifice from the earlier novel here irrigates the soil of the Tiganan homeland. Myth, sexual desire, and Jewishness are again sublated in the novel’s, and the character’s, subconscious.

Kevin Laine returned a third time in Kay’s 2007 bestseller Ysabel, a kind of exorcism of Fionavar and its preoccupations. Unlike his other novels, it is set entirely in the present day of our own world. The fantastic element takes the form of characters from Roman and Celtic antiquity who break into our 21st century, threatening to take possession of the novel’s protagonist and his friends in order to reenact their ancient story. The main character, Ned, is a teenager who accompanies his photographer father on an assignment to Provence. He ends up having to rescue his father’s assistant Melanie when she is possessed by Ysabel, a two-thousand-year-old woman who has been fought over for centuries by two rivals.

Ysabel is a meditation on the allure and danger of being overwhelmed by the intertwined forces of fantasy, of erotic desire, and of the mythic stories that come before us. For the first time in Kay’s post-Fionavar novels, he brings back his earlier characters. Ned’s aunt and her husband turn out to be two of the students from the Fionavar trilogy—though it is the dead Kevin who presides over the novel, his sacrifice a talisman that protects the characters from harm at one point, and who is eulogized by his now middle-aged friends in words lifted from those first books.

Ned reprises the role of Kevin, though without his Jewishness. Kay sets the Fionavar redux scene with, again, a boar, a cave, a chasm, and a woman-goddess transfigured by the power of eros. But this time, Ned interrupts the myth and breaks the cycle of romantic sacrifice. The poignant but unachieved hope of the Fionavar novels, to rewrite the story and assert control over myth, finally comes to pass here. Regarding the ritual he has derailed, Ned realizes: “They had collided with a wall—with him—and the intricate spinning had come to a close on this mountain. . . . It was not preordained, what had just happened, not compelled.”

Kay allows Ned not only to withstand the force

of myth and narrative but of erotic desire as well. The vivacious Melanie,

still partly possessed by Ysabel, kisses Ned at the edge of a literal and moral

precipice—but they go no further, and there is

neither Kevin’s erotic apotheosis-suicide or a betrayal of Ned’s more

age-appropriate girlfriend waiting for him at home. A question, perhaps

unanswerable, remains: Did Kay find it necessary to leave out Kevin’s

Jewishness in order to achieve this more peaceful resolution?

In any case, Melanie returns to her human self, and Ned decides to descend the mountain, physically and symbolically moving from the exalted plane of myth to the more difficult, mundane one of choice:

His turn to look away, out over so much darkening beauty. “We should get down. This isn’t a normal place.”

“Neither are we,” said Melanie. “Normal. Are we?”

He hesitated. “I think we mostly are,” he said.

The new novel takes place in the same world as Kay’s other historical fantasies, in an Italy roiled by political rivalry and haunted by the fall of Constantinople. There is much period flavor, and the central action sequence is a version of the Palio di Siena, a centuries-old festival and horse race that today attracts thousands of tourists. Kay’s many fans have hailed the book as one of his best, but I was not won over. The main characters—the poor-kid-made-good Guidanio Cerra, the highborn rebel Adria Ripoli, and the freethinking healer Jelena—are not especially vivid or engaging, even as the melodramatic types they are. Moreover, they are so modern in their outlook and are rewarded by their author to the extent that they do not take their historical horizons seriously; their Renaissance context feels at times like stage decoration.

More interestingly, Kay periodically arrests the narrative of palace intrigue and derring-do in order to focus, as the title suggests, on how his characters recall their choices years later. Rather than weaving a neat tapestry, Kay pulls at the individual threads of his protagonists, suggesting random entanglement rather than organic design. This may be another of Kay’s challenges to the determinism of epic fantasy—or of history. And yet, because of the deficiencies in characterization, the overall effect lacks the emotional impact Kay is aiming for.

Given the novel’s focus on remembrance, it seems appropriate that Fionavar returns once again in ghostly fashion. In an odd interlude, Jelena picks anemones, the red flower of Adonis and Kevin. “A favourite, that flower, associations going a long way back,” Kay writes. She then encounters a mysterious woman who wears a distinctive ring that identifies her as one of the characters from the Fionavar novels. But the apparition vanishes, and the brief episode takes place in a graveyard.

Suggested Reading

A Journey Through French Anti-Semitism

There is a problem with the inevitable reflexive warnings after every vicious attack not to slip into Islamophobia. A short personal history of how France got here.

If God Wills It, a Broom Can Shoot

“Are you really intending to raise our kids,” my wife Tali asked me one Saturday afternoon after our Shabbes lunch, “in a world that doesn’t have Harry Potter in Yiddish?”

Equine Ambles into a Watering Hole: An Interview with Jessica Cohen

An interview with Jessica Cohen—winner of the 2017 Man-Booker International prize for her translation of David Grossman’s Horse Walks Into a Bar—on translating Hebrew literature and jokes.

Tradition, Creativity, and Cognitive Dissonance

What are the conditions for a Jewish intellectual renaissance? Disagreement is one, inconsistency might be another; look at the early Zionists.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In