The Poet from Vilna

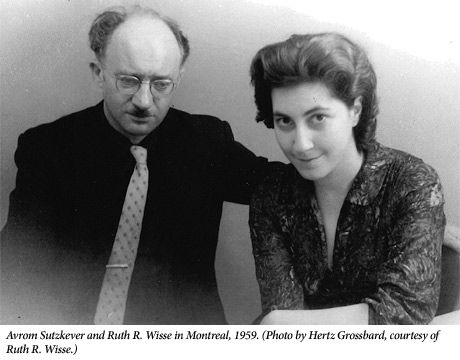

On the 6th of June, 1959, I arranged a rendezvous for the Yiddish poet Avrom Sutzkever, who was then on his maiden visit to North America. Unable to get a visa for the United States, he had come on a speaking tour of several Canadian cities, spending most of his time in Montreal, where I was living at the time. Quite a number of his friends who had known him before the war and writers who wanted to meet him for the first time made the trip across the border, swelling the audiences for his public lectures and readings. But the meeting I set up for him was to be secret and private. On the agreed morning, my husband Len and I drove Sutzkever to the Montreal airport where we picked up his visitor and then took them both to a cottage we had booked at La Chaumière, a secluded lodge in the foothills of the Laurentian Mountains. Once we saw them settled, we drove back to the city, returning the following afternoon to execute the plan in reverse.

Sutzkever’s clandestine visitor was Max Weinreich, linguist and historian of the Yiddish language, who had been his mentor in Vilna before 1939. The two men had not seen one another in twenty years. When the Germans invaded Poland, Weinreich happened to be attending a conference in Denmark with his elder son, Uriel. Father and son left for the United States, where Max took time off from his Yiddish scholarship to write Hitler’s Professors, documenting the participation of some of Germany’s most distinguished thinkers in the Final Solution. Meanwhile, Sutzkever and his new bride Freydke had been incarcerated with some 80,000 fellow Jews in the double ghetto that the Germans set up soon after they occupied Vilna in the summer of 1941. They were among the few who survived the massacres and deportations, reaching Moscow in March 1944, Paris (via Vilna and Lodz) in 1946, and Tel Aviv in 1947.

“It is true that we deal in words, each of us in his fashion,” Weinreich wrote to Sutzkever when they established a correspondence after the war, “but it doesn’t require words to express what we feel for one another.” It was Weinreich who had asked that their meeting be private so that they could spend their short time together without fanfare or interruption.

Len and I had met Sutzkever two years earlier, during our honeymoon in Israel, and I was now shepherding him around Montreal, but I had not met Max Weinreich before. The three of us waited in the reception area, and when Weinreich emerged from the swinging doors, Len and I hung back as the two men greeted each other.

Their reunion was the most dramatic I was ever to witness. No more than a long hug betrayed their nervous joy, but I knew from the eagerness of some of the letters and phone calls leading up to this moment how badly they wanted to be face to face. Lithuanian Jews—as compared with their reputedly more warm-blooded and earthier Ukrainian, Galician, and Polish kinfolk—are known for their passionate reserve. Weinreich and Sutzkever never switched from the formal to the intimate second-person form of address. As Weinreich wrote in one of his letters, they would always have “weightier subjects” to talk about than their feelings.

Weinreich, nineteen years the elder, had founded in Vilna the Jewish scouting movement Bin (Bee), in whose magazine the nineteen-year-old Abrashe—as he was then known to his intimates—published his first poem, in 1932. Weinreich was also co-founding director of Vilna’s Yidisher Visnshaftlekher Institut (YIVO Institute for Jewish Research), where Sutzkever came in the late 1930s to pursue his interest in Old Yiddish literature. When they had last seen one another, Sutzkever was transposing the early epic, Bove Bukh, into modern Yiddish, and Weinreich was touting Vilna’s talented emerging poet as one of the YIVO’s best fellowship students.

Now, the seniority appeared to be reversed. For one thing, Sutzkever had been there. Among my parents’ friends I had noticed how those who had survived the war in Europe were treated as valued messengers from the beyond. “I saw Nadushka right before the February roundup.” “Berl was still alive the day the SS came to pick up Wittenberg.” “The child was already skin and bones.” “Their farmer betrayed them.” In general, refugees occupy a lower social status than settled immigrants, but in this case the testimony of those who came to be known as survivors often lent them authority that far exceeded that of earlier arrivals. And Sutzkever was more than such a witness. The young poet, who had continued writing and reading his poems in the Vilna ghetto, had become a symbol of its creative resistance.

On the strength of his reputation, he and his wife had been airlifted from occupied Poland to Moscow, where he wrote In vilner geto, an itemized account of the horrors of the Final Solution in Vilna. The Soviet writer Ilya Ehrenburg convinced the Kremlin to have Sutzkever testify on behalf of Russian Jewry at the Nuremberg Trials. A clip of him refusing the court’s invitation to be seated is available on YouTube. He delivers his testimony standing at attention like the soldier he could not be during the massacres he is describing. Of the aftermath of one roundup he says, “It looked as if a red rain had fallen.”

As part of his work in the ghetto, Sutzkever had organized the concealment of the most precious materials in the YIVO archives. After the war, he defied Soviet prohibitions and arranged for their transfer to Weinreich in New York. The student was now more experienced than his instructor in what the world had to teach.

I was twenty-three at the time of their meeting, two years married, two years out of college, working as Press Officer for the Canadian Jewish Congress, under whose auspices I had arranged Sutzkever’s Canadian visit. I had no idea what I “wanted to do with my life,” though that weekend I wished for nothing more than to act as go-between for these two men. Vilne was my ancestry no less than theirs. My maternal grandmother, Fradl Matz Welczer, had run a publishing house in Vilna when it was still part of the Tsarist empire. My mother was raised in Vilna’s modern Yiddish and Hebrew culture when the city was Polish between the World Wars, and my father was class of 1929 in chemical engineering from Vilna’s Stefan Batory University. When my grandmother contracted tuberculosis, her doctor was Tsemakh Szabad, about to become Max Weinreich’s father-in-law. On one of his last visits, the doctor said, “You can’t patch up silk.” This intended compliment to my grandmother’s refinement my then-fifteen-year-old mother correctly heard as a death sentence. She never forgave the good doctor his diagnosis. I myself had never been to Vilna, yet thanks to stories I had been hearing since childhood, I felt I knew the “green bridge” across the River Viliye as well as I did the one across the St. Lawrence seaway.

Shortly after that day spent ferrying my betters, Sutzkever asked me what I was planning to do in the future, implying that my job at the Canadian Jewish Congress was not commensurate with my abilities. Flattered by an assessment I fully shared, I said I would probably pursue a graduate degree in English literature. “Why don’t you study Yiddish literature?” he asked. I laughed, “And what would I do? Teach Sholem Aleichem?” Those words were no sooner blurted out than I realized how I had insulted Sutzkever and the culture in which I had been raised. I had been making arrangements with a local impresario, Sam Gesser, for a Folkways recording of Sutzkever reading his poems: why, then, should I have questioned the status of Yiddish literature? I had been reading Sholem Aleichem since I was in grade school, so why doubt that he could be taught—or taught by me? When I tried to explain to Sutzkever that universities did not include Yiddish in their curricula, he informed me that Max Weinreich was in fact teaching Yiddish at City College and that his son, Uriel, ran a graduate program in Yiddish at Columbia University where one could study both literature and linguistics.

The next day, I called Columbia to see how soon I could begin. Uriel arranged for my admission to the doctoral program in English and Comparative Literature, with Yiddish as my main secondary field. My husband supported my decision, and for pocket money I got a job teaching Jewish Sunday school in a suburban synagogue. I fancied myself independent, like those young men in 19th-century novels who go to the big city to seek their fortunes. It never occurred to me that during the two men’s time together, Weinreich might have shared his concerns about the lack of students, or that Sutzkever might have been serving as his recruiter.

As it turned out, Uriel was on leave in Israel the semester I came to Columbia, so he arranged for his father to conduct a private weekly tutorial for me, his only graduate student in Yiddish literature. “Ruth Wisse has arrived,” Max Weinreich wrote to Sutzkever in January 1960; “we will be devoting a semester to Mendele (the Yiddish and Hebrew writer, Mendele Mocher Sforim). “She is the kind of student vos ‘bagert‘ and she has a feeling for literature and good common sense.” Bagern, like the German begehren—a word Weinreich placed in quotation marks—means to desire, to crave. Students are sometimes said to crave learning, but used as it is here, without an object, the verb suggests that I must have seemed hungry for more than literature.

He was probably right. There was more erotic adventurism in my decision than the common sense for which he gave me credit. These two men were tested in a way that my coddled cohort of friends could never be. Giving not a thought to the practical outcome of my decision, I wanted to prove myself at least as daring as they were.

Weinreich and Sutzkever exuded potency—the quality that I had always associated with Yiddish. It was maddening in the years that followed to hear people say, upon learning what I studied, something like, “Oh, I spoke it with my grandmother,” or, “Isn’t Yiddish a dead language?” I never took the trouble to explain that I was attracted by the virility of Yiddish, whose exemplars were so much grittier than Shelley, a writer I was studying simultaneously, and livelier even than Samuel Johnson, then my favorite British author. It was the youthfulness of Yiddish that appealed to me. At Columbia, I worked on the literary group Yung Vilne, of which Sutzkever had been a member, and my first book on Yiddish literature was on the group’s New York counterpart, Di Yunge.

Reading about the Second World War, I concentrated not on Jews who were led “like sheep to the slaughter” but on the songs of Leah Rudnitski, the heroic feats of Abba Kovner, the soup kitchen Rochel Auerbach ran in the Warsaw ghetto, and Yitzhak “Antek” Zuckerman’s exploits on the Aryan side. These people had all been under the age of thirty.

Grittier than Shelley: When speaking of the war, Weinreich insisted we say not Nazis, but Germans. “One does not refer to international conflicts by political parties, but by the countries that fought them: This war was prosecuted by Germany.” As a graduate of the University of Marburg, Weinreich was sometimes consulted by post-war German scholars. He told me he never entered into correspondence with anyone from Germany without first asking for a full account of the person’s actions during the war.

We would have these conversations after our weekly tutorial over dinner at a Chinese restaurant on Broadway near 125th Street, where he and the waiter discussed distinctions between dumplings and kreplakh. After dinner, in the late wintry hours, I accompanied him to his subway stop at Lenox Avenue; we were usually the only white people on the bustling street. Only later did I realize that my teacher was blind in one eye, courtesy of anti-Semitic students who had attacked him in Vilna—and that this builder of institutions and author of the 1937 social science study, Der veg tsu undzer yugnt (The Way to Our Youth), was undertaking this weekly effort for the sake of a single student.

As for Sutzkever’s own nerve, the first book of his poems he gave me, Ode to the Dove, contained this “Song of the Lepers,” from a cycle inspired by a visit he had made to South Africa:

Warrior, dip your arrows in our blood,

The enemy will lose his feet.

Our blood is not from father-mother

But God’s spit in crippled limbs.

When we die, the earth will boil like sulfur

Our blood can set water afire.

Warrior, dip your arrows in our blood

Whoever is struck-will not live.

Merely touched by its shadow-he will not live.

If the arrow misses its target-the fire endures.

Lightning birds in high nests of thunder

Singing, fall dead into the abyss.

We ourselves, we have no fingers,

We cannot rush the enemy-

Warrior, dip your arrows in our blood.

The leper-pariahs who turn their disfiguration into the deadliest of weapons are taking aim at an enemy otherwise beyond their reach. Accursed, they curse. Condemned, they condemn. Despised and feared, they deliver their sentence of death. The song reminded me of the closing lines of the 137th psalm, where the captive Jews of Babylonia charge others to wreak the vengeance they cannot exact on their own. The leper colony Sutzkever visited in Africa had obviously reminded him of the ghetto, but where was the poet in relation to this poem? Was he the avenging warrior whom the lepers urge to dip his arrows in their blood, or was he one of the powerless, inciting others to wreak vengeance on their behalf?

Because both Weinreich and Sutzkever godfathered my Yiddish studies, I became aware of how differently they assessed the future of our common project. Weinreich’s confidence waned over the next decade, or more precisely, until his death in 1969, as Sutzkever’s grew. This was certainly not due to any competition between them. In fact, what drew my attention to the asymmetry of their expectations was the intensity of their mutual regard. One often spoke to me of the other with the same ardor they had displayed in Montreal. Nor did the difference in age seem decisive. In many respects, Weinreich was exceptionally youthful; I might have said about him, er bagert. He headed an apparently thriving institution in opulent America and was engaged in the culmination of his life’s work— the definitive history of Yiddish from its origins in Western Europe, a subject independent of the fate that befell the speakers of the language. By contrast, Sutzkever occupied a small office in a Tel Aviv government building, working under a daily burden of grief— as one of his poems puts it— to keep the dead from dying.

During my years at Columbia, the YIVO in New York appeared to be the thriving successor of its destroyed Vilna branch. My favorite haunt was the reading room on the second floor of its building at 1048 Fifth Avenue (now the Neue Galerie, which I have never had the heart to visit). I enjoyed the heavy traffic inside the building, the permanently harried state of Dina Abramowitz who oversaw the library, and the steady rise and fall of its dumb waiter bringing documents to and from the archives below. In 1960-61, the annual conferences drew standing-room-only crowds. But Sutzkever saw things differently, or perhaps Weinreich took him into his confidence. He regretted that Max had not accepted the chair in Yiddish that the Hebrew University of Jerusalem offered him in 1952. When I asked Weinreich about this, he said that not having contributed to the building of Israel, he was not entitled to accept its bounty, but he may also have preferred to head his own institution in New York, where his wife and sons had already been resettled and where he now belonged as he had once belonged in Vilna.

But as the time approached for publication of the History of the Yiddish Language, I began to share Sutzkever’s doubts about whether Weinreich had truly succeeded in grafting a strong branch of Jewish Vilna in New York, and about his own assessment of what he had achieved. The complete History came to four volumes—two of text and two of footnotes. When the YIVO’s Board of Directors tried to persuade the author to publish only the text, as a cost-saving measure, Weinreich was as bitter as I ever heard him. He said that in any case his work would have only ten readers—who would, however, be precisely the ones to want the notes.

Sutzkever happened to be in New York during the negotiations. Infuriated by this snub to the world’s leading Yiddish scholar, he accompanied Weinreich to the board meeting, ostensibly as a guest, and berated the members for basking in the glory of their office while nickel-and-diming the man who earned it for them. I had no way of knowing if Sutzkever was reporting on how things really happened at the meeting, but both men credited him with securing the funding for all four volumes. Weinreich thenceforth spoke of his champion as a mentshn-kener, someone more adept than he was at dealing with people.

I don’t think that Sutzkever understood people any better than Weinreich did. Any attentive reader of Sutzkever will recognize how little insight he even attempts to offer into any soul but his own. He seemed rather to know his own strength, certain that he could set wrongs right. The preeminence he ascribed to poetry persuaded him that he had supernatural powers, and no doubt this confidence gave him more than ordinary influence over others.

He, Freydke, and their infant daughter, Rina, arrived in Tel Aviv in 1947, shortly before Israel’s independence. Food was rationed, Arab armies were poised to invade, the provisional Jewish government had its hands full, dealing with the British blockade of arriving refugees on one and resettling those who made it through on the other. Exigencies of absorption and defense ratcheted up the importance of consolidating Hebrew as the common language of incoming Jews from east and west. Sutzkever, however, was bent on founding a Yiddish literary journal. He was warned that the odds against getting financial support were greater than they had been against his survival in the ghetto, but took that as proof that he would prevail. With the help of Zalman Shazar, who would later become the third President of Israel, he secured the financing he needed from the Histadrut, the Federation of Labor, and in 1949 started up the journal Di goldene keyt, named for the golden—unbroken—chain of Jewish tradition.

For the next fifty years, Sutzkever’s Yiddish quarterly was the central meeting point for a dispersed and depleted literary community. Around him there gathered a new group of poets and writers, Yung Yisroel—Young Israel. The American modernist Yiddish poet I.L. (Judd) Teller, who had stopped writing verse at the start of the Second World War, credited Sutzkever for his return to it. Di goldene keyt helped to defuse the conflict between two Jewish languages, enticing some Hebrew writers into Yiddish and raising the profile of Israeli culture in Yiddish. With the help of the Tel Aviv municipality, Sutzkever established a prize for Yiddish named for the poet Itzik Manger, who settled in Israel before his death.

Sutzkever liked to tell the story (which has been claimed by others) of being stopped on a stroll through the ultra-Orthodox neighborhood of Meah Shearim by a small boy who asked him why he wasn’t wearing a hat. “The sky is my hat,” he answered smartly. “Too small a head for such a large hat,” the child replied. Actually, Sutzkever shared the child’s sense of proportion in national as well as metaphysical terms. From the moment he arrived in the country, Sutzkever drew inspiration from the land, by which I mean not only its people, and not only the idea of “a third Jewish commonwealth,” but also its wadis and animals and stones.

I had come to know something of this first-hand, before the rendezvous in Montreal, back in the summer of 1957, which Len and I spent in Israel. We had married in March of our graduating year— I from McGill University, he from the Université de Montréal Law School— and decided to go to Israel for what Yiddish calls the “kissing weeks.” We were mostly in Tel Aviv, rooming (on Sholem Aleichem Street!) with a family my parents had known in Europe, but we explored as much of the country as we could. The poet Melekh Ravitch, with whom I had read Yiddish literature in Montreal, had provided an introduction to the well-known Avrom Sutzkever.

I dutifully called him shortly after we arrived. He was correcting proofs, and suggested we join him at the publishing house. Emerging to greet us, he looked just like the person in the photograph Ravitch had shown me, a trim man with a neat moustache, in white short-sleeves, wearing a cap against the sun. From behind glasses, the blue eyes gripped us, seeing and taking note. Apparently satisfied, he invited us to attend a wedding with him and his wife the next night. Len and I were incredulous. We had spent anxious weeks before our wedding paring down lists of relatives and friends, yet here was an almost-stranger inviting us on the spot to a wedding of children of friends who were “certain,” he assured us, to welcome us. His wishes, it seemed, were everyone’s command, and soon became ours as well.

Shortly afterward, on a visit to the Sutzkevers’ apartment, Len and I described what we had already seen of the country and mentioned a planned road trip to Eilat. Sutzkever proposed a slightly different route: Why not drive to Ein Gedi—the oasis near the Dead Sea where David had hidden from an irate King Saul? He and his daughter Rina, by now a teenager, were eager to see the area and could join us on our expedition. Before we knew it, we were discussing dates for the upcoming trip. When we later ran this by Didi, the son of the family with whom we were staying and our companion-guide on these travels, he was less enthusiastic. Having been through the army, he knew the terrain and was worreid. The secondary roads past Beersheva were poorer than the highway to Eilat. One needed military permission to drive to Sodom. Civilian vehicles were probably not allowed near Ein Gedi, which was virtually at the border with Jordan. Five people in a car (this was before air conditioning) might not be comfortable driving through the desert in the middle of summer. Where would we stay in Beersheva or in Sodom or in Ein Gedi? There were no hotels.

But if Didi had served in the army, Sutzkever had survived the Vilna ghetto. All obstacles swept away by his enthusiasm, we rented a car and set out, with Len driving, Sutzkever riding shotgun, Rina and Didi in back with me in the middle. There being no hotel rooms in Beersheva, the five of us shared a huge room in a sheikh’s house with beds along the walls, dormitory style. Long after the others were asleep or pretended to be, Sutzkever asked me to go on telling him all I knew about the Yiddish writers of Montreal. The next morning, we consulted the police about the route before ignoring their warning not to proceed without military escort. The sight of Sodom when we reached it at midday called to mind the punishment heaped upon it in Genesis 19. A soft-drink and sandwich stand squatted at what looked like the end of the earth.

In sum, all of Didi’s qualms had proved justified. But, thankfully, Sutzkever’s nerve prevailed. At the solitary gas pump a young man introduced himself as a member of the kibbutz at Ein Gedi, offering to act as our guide in exchange for a lift. The road? No problem. Accommodations? The kibbutz would be glad to have us. We could swim in the fabled oasis pool and visit King David’s cave. Long before we reached our destination, our guide confessed his deceit. The “road” was only a jeep path over rough terrain. He had missed yesterday’s scheduled transportation and had we not come along, he would have had to wait another two days for the next van. But he did know the route, and once we reached our destination we were indeed given a short tour of the kibbutz, including a swim in the fabled pool and visit to the cave, supper in the common dining hall, and five outdoor cots for the night. As we lay down under the stars our hitchhiker came to advise us that it would be best for the tires if we started out before sunrise the next morning.

I have not been back to Ein Gedi since then, except in Sutzkever’s poems recalling the trip. Naturally, he had felt a kinship with the psalmist “behind the waterfall in David’s cave,” inspired to write his own song, “A Mizmer in Ein Gedi,” about the place where

I walk inside your veins.

My heart beats in yours.

I am a prayer dressed in wounds

Like a tree

arrayed with birds in a storm.

But the best of that trip was yet to come. Though we missed breakfast, we were rewarded by wondrous sights— clusters of cranes at the edge of the water and young deer prancing across a still and empty landscape. There was nothing manmade on the horizon. We drove as slowly as we could, so as to be less intrusive than we already were, and because we knew ourselves uncommonly blessed.

When I began studying Sutzkever’s poetry, I realized that he had actually already visited the shore of the Dead Sea once before. One of my favorite poems, “Deer at the Red Sea,” was composed in 1949. It also dawned on me that since he did not drive, Sutzkever always had to arrange such trips more or less like the kibbutz member who needed a ride. He could not see the land without transport, and it was imperative that he grow intimate with the land.

Sutzkever’s translators, even Benjamin and Barbara Harshav, who have supplied what is so far the largest selection of Sutzkever in English, and his biographers, even the incomparable Abraham Novershtern, who has produced the most reliable overview of Sutzkever’s life and writing— indeed, all who have written about the poet to date— inadvertently slight his poems of Israel. This is understandable given the more obvious drama of his pre-Israel life and the greater rhetorical force of his earlier verse. But Sutzkever started out as a poet by finding the signature of the Eternal in nature, and the discovery of nature in Israel was the corollary of that intuition. When he accompanied the army into the Sinai in 1956, he was also getting to know the landscape. He even navigated the cafés of Tel Aviv like an explorer of suns and shades. He drew much strength from the land—in this sense most differently from Max Weinreich who had been imbued in his Vilna youth a love of his physical surroundings but formed no similar attachment to New York. Sutzkever is one of Israel’s modern psalmists. Were I choosing a thesis topic today, I would start with the Dead Sea poems and trace his discovery of the land.

For my Master’s thesis at Columbia in 1961, I translated and wrote a commentary on a series of Sutzkever’s prose poems, Green Aquarium, that recalled the final days of the ghetto and the kinds of courage that Jews manifested in its aftermath: A partisan and Polish Catholic nun bring a dead boy to burial in the middle of a rain-soaked night; a partisan and his lover are separated and reunited in the swampy forest; two lovers conduct a romance from neighboring chimneys. These works are all about beating back death. Several years before I was to hear Theodor Adorno’s pronouncement that “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric,” or to read the essay in which he contends that our whole world is becoming “an open-air prison,” I was persuaded by Sutzkever’s contrary definition of poetry as the only credible alternative to barbarism. Governed by an autonomous standard, impervious to the Germans’ depravity or any corruption, poetry was for Sutzkever not another casualty, but rather the antidote to Auschwitz.

Teaching Yiddish literature over a lifetime, I have Sutzkever and Weinreich to thank for my profession, though nothing thereafter ever went quite as smoothly as my admission to Columbia. For a number of reasons, I returned to Montreal without completing a doctorate, and eventually began graduate work afresh in McGill’s fledgling program in English Literature. Meanwhile, I stayed in touch with Max Weinreich and visited New York periodically to be guided by him on the Yiddish study that I was pursuing on my own. His death on January 29, 1969 hit me much harder than his son Uriel’s even less timely death had two years earlier.

When I learned the news, I took the night train to get to New York for the funeral. I was in a rage, as though Weinreich had died to spite me. Our next meeting had been scheduled— I had his postcard in my purse— but he had followed his son to the grave instead of remaining my tutor and friend. And the funeral was spiteful: Max had given orders that there was to be no prayer, no Yiddish hesped or English eulogy, no words or music. We mourners sat in the silence to which the deceased had condemned us. I suddenly understood something I had read in a story by Isaac Bashevis Singer. The expression opshrayen a mes is used to describe a woman who screams a corpse back to life. This expression had made no sense to me when I read it, but leaning over the casket I said aloud, “Ikh vel aykh opshrayen fun toyt!”— I will scream you back from death! For a moment I was convinced that my fury could overpower his too great willingness to die. Yet as he did not rise from his coffin, I joined one of the buses taking us to the cemetery and even shoveled some obligatory earth into his grave.

Sutzkever fought his despair to a better end. A recurring highlight of my visits to Israel was the prospect of one or more rendezvous with him at one of his favorite hangouts. When he could no longer navigate even the short distance from his apartment building to the nearest café, we would be served tea in his living room by a part-time housekeeper. Our last visits were at Beit Shalom, a supervised residence just a few blocks from a café on Dizengoff that we once frequented. At the home he joked with attendants as he once had with the waitresses who used to reserve his favorite table. The staff respected and helped him maintain the fastidiousness of his dress. He suffered the indignities of a failing body with dignity, but he had not wanted to age, and did not reconcile himself to the process.

No official representatives of Israel’s government attended Sutzkever’s funeral on January 24 of this year. The poet would have been hurt by the slight. But President Shimon Peres was among dozens of notables at a large public commemoration held at the end of the month of mourning, and Dan Miron, a professor of Hebrew literature who has written splendidly about Sutzkever, informs me that the mayor of Tel Aviv intends to name a street after him. In one of his early poems, Sutzkever asks to be permanently “enfaced” in the radiance of Sirius, the morning star. I am sure he has been, but he may also soon be wryly pleased by his humbler enfacement in Tel Aviv.

I doubt that New York will name a street for Max Weinreich. Is it too much to hope that their two names might grace intersecting streets in their beloved Vilna, a city whose fame they will carry into history? Neither of them would have sought the honor, but should it come about, the city’s fame will grow on their account.

Suggested Reading

The Living Waters of History

A historical novel about the Spanish Expulsion tells us as much about current reading trends as it does the lives of Jews in 15th-century Spain.

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?: A Rejoinder

To sharpen Stern’s point, we may say that the person who believes God literally gets angry metaphorically angers God.

Category Error: A Response & Rejoinder

Yoram Hazony responds to Jon D. Levenson's critique of his book. Levenson replies.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In