Wandering Jews

The late and lamented travel documentarian Anthony Bourdain won his daily bread by introducing Americans to distant places, exotic cuisine, and fascinating people while uttering truisms in trademark voice-overs: “The journey is part of the experience, an expression of the seriousness of one’s intent. One doesn’t take the A train to Mecca,” he intoned on one occasion. “I urge you to travel as far and as widely as possible. Sleep on floors if you have to. Find out how other people live and eat and cook. Learn from them, wherever you go,” he advised on another. The animating philosophy of shows like Bourdain’s is a kind of roving humanism. And yet just as there are many ways of inhabiting a place and making it home, there are just as many ways to leave it and visit others. Everybody travels, but how they do so is culturally specific.

Consider the Jews. The Hebrew Bible recounts how the Israelites went down to Egypt, wandered through the desert for forty years, and then conquered, settled, and were later exiled from the Promised Land. The postbiblical Jewish diaspora has been a long and often violent sequence of expulsions and dispersions, punctuated by relatively brief moments of refuge and stability. Dramatic movement has also characterized modern Jewish life, with its huddled masses fleeing for American shores and its ingathered exiles realizing Zionist dreams.

To take a portrait of Jewish life is to produce a moving picture, as Joshua Levinson and Orit Bashkin demonstrate in their superbly edited volume, which covers Jewish travel writing from the Bible’s peripatetic patriarchs to contemporary pilgrims signing guestbooks at Jewish heritage sites, like Rachel’s Tomb. Travel gets the Israelites going when Abraham receives the call to go to the land that God will show him, and it is invoked in the final verse of the Tanakh’s last book, when King Cyrus issues a proclamation for exiled Judeans to go up to Jerusalem.

Again, it is not so much the fact of travel that is interesting but its particular meaning—and direction—that is instructive. Levinson observes that Odysseus famously journeys home to Ithaca from faraway Troy, while Abraham sets out from his home in Ur to travel to a land unknown. This unusual national origin story turned out to be an asset for the Jews, who roamed the diaspora for two thousand years. It also exacted a price.

The Jewish experience is still sometimes summed up with the phrase or the figure of “Wandering Jew,” without a very clear memory of who or what that was. As the distinguished Israeli folklorist Galit Hasan-Rokem writes at the outset of her contribution to Jews and Journeys:

The Wandering Jew is the most well-known and widely distributed figurative expression of the various ways in which Jews have been conceptualized as mobile and itinerant in a wide range of texts from popular anonymous chapbooks to masterpieces of early modern and modern art and literature.

In the standard telling, the Wandering (or Eternal) Jew witnessed Jesus’s crucifixion and was then damned to roam the world endlessly, bearing the unbearable weight of Jewish guilt.

It is an anti-Jewish legend that takes old Jewish ideas and ways of self-knowing and twists them into a freakish specter. According to the book of Deuteronomy, an Israelite farmer bringing new fruits to Jerusalem must tell his people’s story by invoking his forefather as, incredibly, an Aramean gypsy: “My father was a wandering Aramean” (Deut. 26:5). It was not only Abraham but also later biblical forebearers, such as Jacob and Joseph, whose lives were punctuated by travels to, from, and between Mesopotamia, Canaan, and Egypt. The faith the patriarchs and matriarchs maintained despite their hard life on the road is remembered in Jewish tradition for a blessing. In the legend of the Eternal Jew, perpetual Jewish motion becomes instead an expression of theological obstinacy.

Scholars have identified the roots of the Wandering Jew among the writings of Church Fathers like Augustine, who applied the curse of Cain to “wander restlessly on the earth” to the Jews for killing Jesus. More broadly, Christian theologians argued that the diaspora was a punishment for the Jews’ failure to live up to their covenant with God. This, too, drew upon an old biblical calculus: if inhabitants of the Holy Land led moral lives, the land absorbed them. If not, it spewed them out.

Like its subject, the legend of the Eternal Jew wandered over the span of centuries, turning ever more strange, sour, and dangerous with the passage of time. It first appears in recognizable form in medieval Italian and English monastic chronicles and later wanders into early modern Central and Northern Europe chapbooks, in which the figure is given a name and a profession—Ahasuerus the Cobbler. How the Eternal Jew got the name of the Persian king in the book of Esther is anybody’s guess. More than half a century ago, the great scholar of ancient law David Daube argued that the name reflects the Christian repurposing of a common nickname for fools in Jewish folk literature. Even if this cannot be proven, Daube’s claim captures the unusual interplay between Jewish and Christian ideas that ultimately produced the Wandering Jew.

Things only began to look up for Ahasuerus during the Romantic period, with its inversion of previously scorned values like individuality, rebellion, and wandering itself (wanderlust is one of the Romantics’ greatest inventions). The many guises of the Wandering Jew among modern Jewish writers who adopted it likewise echo shifts in Jewish belief. For some, he was an old school Jewish penitent seeking forgiveness through self-imposed exile, whereas for others he stands for the exiled Divine Presence, the Shekhina herself.

On the other hand, both Zionists and socialists actively rejected the Wandering Jew, and with it, they hoped, Jewish wandering. And yet, the figure endured and became synonymous with modernity, rambling about town like Joyce’s Leopold Bloom, “surveying the borderlands of Jewishness from all sides, within and without, and emphasizing Jewishness as an open, instable, creative, and ever-developing cultural field.” That nice formulation is Hasan-Rokem’s and would, so it seems, reflect her own values as well.

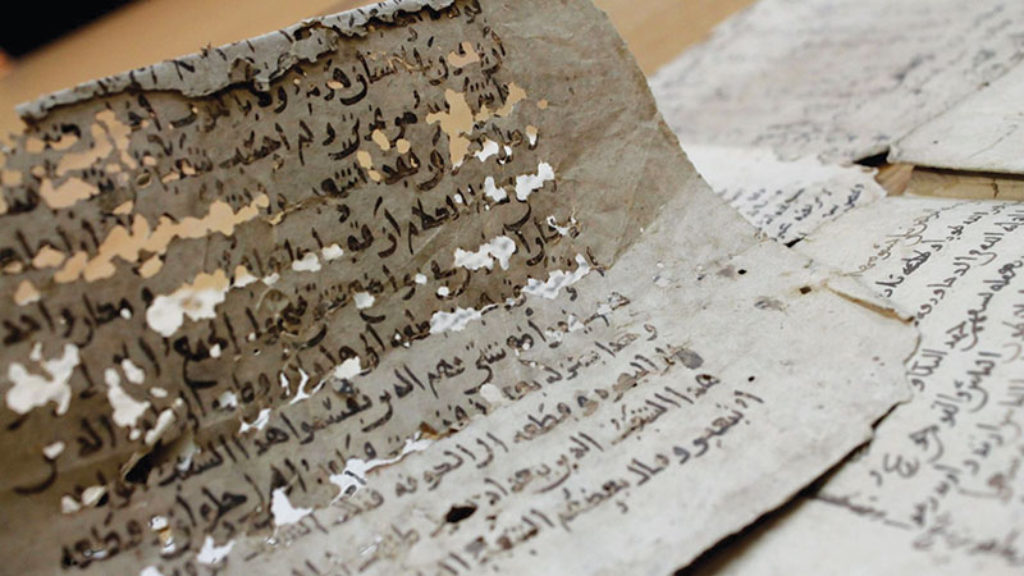

For those interested in original travel writing connected to real, rather than literary, wandering Jews, Miriam Frenkel has uncovered a remarkable trove of letters preserved in the Cairo Geniza. Medieval Jewish vagrants used these letters of introduction to vouch for themselves and the charity cases they represented. In turn, their recommenders used the bearers of the letters as a reliable if unconventional postal system.

Some of these letters beautifully channel the tragic voice of the wretched, undoubtedly illiterate, wandering men and women who carried them: “I wander about like a lonesome bird on a rooftop. . . . I am naked, thirsty, destitute, and have no means of sustenance.” But they also reveal the scholarly concerns of the rabbinic recommenders, such as Judah ibn al-‘Ammānī, who wrote to Meir bar Abū al-Thābit Yākhīn about some Rosh Hashanah prayers that he had composed and sent with a “dark-skinned and thin” vagrant named Samuel ha-Kohen of Baghdad:

When that man, Samuel, told me: “I am going to Al-Mahalla and will stay there for two or three days, after which I will then head directly to Fustat without any delay,” I said to him: “Be careful not to forget the penitential prayers when they are needed, because if you fail to deliver them, all my efforts and your efforts will have been in vain.” I was afraid that he might not go to Fustat at all, but rather to Cairo, to beg there and then go on begging in the small towns nearby, and then head on his way until he returns to his home in the Holy Land. Please, be so kind as to track him down and get the letter from him. The penitential prayers are attached in a small codex.

According to Frenkel, these medieval letters were part of a social safety net as well as a network of scholarly communication. They also reveal one abiding characteristic of Jewish travel—no matter where you go in the Jewish world, there will almost always be somewhere to land.

Of course, not only poor and illiterate Jews left records of their travels. Take the famous Benjamin of Tudela, who preceded Marco Polo by more than a century and whose name is synonymous in Jewish memory with exploration. Benjamin gave us a highly detailed and often imaginative travelogue describing his journeys from Spain to the Aegean, Levant, Persia, and the Arabian Peninsula.

And there is the important fifteenth-century Mishnah commentator, Rabbi Obadia of Bertinoro, who left his home in the Italian Città di Castello in fall 1486 and sailed to Palermo, where he bumped into another Jewish travel writer, the Italian sugar trader Meshullam of Volterra. From there, Obadia continued on to Messina, Sicily, and then the island of Rhodes before reaching Alexandria, sailing down the Nile to Cairo, trekking across the Sinai, making his way through Gaza and Hebron, and finally reaching his destination, Jerusalem, just days before Passover 1488.

In a clear and pliant medieval Hebrew, Obadia describes the impressive fortress of Rhodes and the crocodiles he sees along the Nile. He meets storms on the Mediterranean and looks on as a sailor is publicly flogged for speaking indelicately. As with Benjamin of Tudela’s Travels, the real gems in Obadia’s epistle are the ethnographic vignettes. In one famous passage, he visits the Cave of the Patriarchs in Hebron, which the Ishmaelites “treat with great honor and fear” and where “each day, bread and lentil stew or a different kind of lentil dish is served to the poor, whether they are Ishmaelite, Jewish, or heathen, in honor of our Father Abraham.”

Obadia also describes the unusual operations at the sacred site. Because Jews and Muslims would not enter the inner crypt:

the Ishmaelites stand upstairs and lower down, via the skylight, burning torches that keep the inside of the cave illuminated. The Ishmaelites who come to prostrate themselves donate coins, which they throw into the cave through those skylights. And when they wish to retrieve the coins they lower a virgin lad into the cave who takes them and comes back up.

Obadia’s main interest was in the Jews and Jewish institutions he encountered along the way. He describes the beautiful and dignified Rhodesian Jews, with their elegant clothes and long hair; the pillars of a stunning synagogue in Palermo without “equal in the whole world”; the mosaic of Cairene Jewry, which consisted of some 500 Rabbinite Jews, 150 Karaites, and 50 Samaritans; and the choreography of Shabbat morning Kiddush in Alexandria:

They sit in a circle on a carpet . . . and all sorts of seasonal fruits are brought and laid on the cloth. The host now takes a glass of wine, recites the Kiddush, and drains the cup completely. The cupbearer then takes it from the host, pours for all the attendees in turn, and each one drinks up. Then the host takes two or three pieces of fruit, eats some and drinks a second glass, while the guests exclaim, “Health and Life!” Whoever sits next to him then takes some fruit, and the cupbearer fills a glass of wine for him, saying, “To your happiness.” The guests exclaim, “Health and Life!” and so it goes round.

With all of the many marvels he witnesses, Obadia is most drawn to consider the subtle differences in familiar things, like whether congregants remove their shoes before entering the synagogue, if the three paragraphs of the Shema are recited quietly or out loud, when the congregation bows on Yom Kippur and what the rituals of Simchat Torah are, how they celebrate their weddings, and how they bury their dead. Even today, not a few Jews seeking adventure abroad find themselves quizzing local Jews about their synagogues, cemeteries, cuisine, and religious customs rather than fully immersing themselves in the spectacle of the utterly foreign.

The most important contribution of Jews and Journeys is its focus on those dynamics of Jewish travel literature that upend basic assumptions of much recent scholarship about travel. Ever since Edward W. Said’s Orientalism, it’s been argued that Western travel writing played a crucial role in exoticizing oriental “others,” with the ultimate goal of “civilizing” and pillaging them. It is, of course, true, as Levinson remarks, that “in one form or another, travel narratives are about the construction and representation of identity; one’s own and an other’s,” and “all travel writing engages in a complex interplay between sameness and difference.” Yet, as the Jewish case makes clear, these interrelations between the familiar and the exotic are anything but a boring binary of an imperial West versus a colonized East.

Since the sixteenth century, the Jewish world has been conveniently, if inaccurately, described as split between the Ashkenazi West and the Sephardi East. The writing that emerges from travel between the two halves of the Jewish globe shows that the West is not always synonymous with power and culture, as we find when Ashkenazi writers encounter an often more cosmopolitan Sephardi world. What is more, the interplay between the Jewish East and West in these writings is largely made possible by a common “oriental” language of communication (Hebrew). Even those few Jewish travel texts that do adopt orientalizing tropes, such as an Argentinian Yiddish story, discussed by Jack Kugelmass, about a love affair with Peru and a native Peruvian, are perhaps better read sympathetically rather than postcolonially. Among other things, this is because these writers were themselves orientalized by Christian Europe and processed that experience in unexpected ways.

The frequent focus on the strange and unusual in travel writing, both Jewish and non-Jewish, should also be charitably reassessed. Marveling at the foreign is not always an attempt to exoticize and subdue. Bourdain used to say that “travel is about the gorgeous feeling of teetering in the unknown.” As an old Jewish blessing puts it, “Blessed are You, Lord our God, King of the Universe, Who Makes Creatures Strange.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

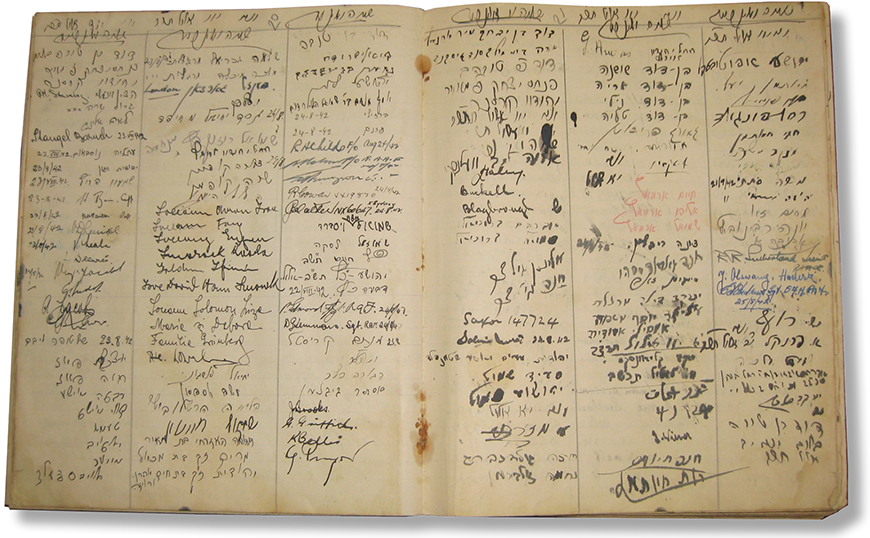

Afghan Treasure

Sometime in the 11th century, a distraught, young Jewish Afghan man named Yair sent a painful letter to his brother-in-law. Life had dealt Yair a tough hand, or maybe it was just his own bad choices.

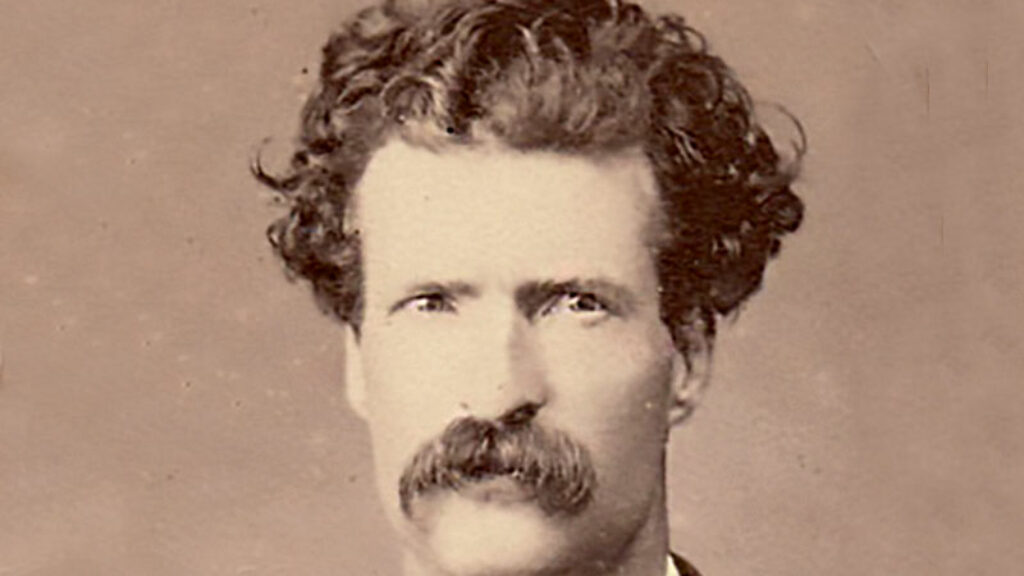

Not So Innocent Abroad

Mark Twain's book about his travels to the Holy Land and back is his bestselling book over the course of his lifetime and remains one of the bestselling travel books of all time.

The Birthright Challenge

Eleven years and four books on, can Birthright Israel save diaspora Judaism?

The Wandering Reporter

Read 86 years after it was originally published, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived can be seen as a chilling and prophetic piece of historical reportage.

j fine

The curse on Cain in Genesis 4:12: כִּי תַעֲבֹד אֶת-הָאֲדָמָה, לֹא-תֹסֵף תֵּת-כֹּחָהּ לָךְ; נָע וָנָד, תִּהְיֶה בָאָרֶץ.

Hosea 9:17: יִמְאָסֵ֣ם אֱלֹהַ֔י כִּ֛י לֹ֥א שָׁמְע֖וּ ל֑וֹ וְיִֽהְי֥וּ נֹדְדִ֖ים בַּגּוֹיִֽם

Amos 8:12: וְנָעוּ֙ מִיָּ֣ם עַד־יָ֔ם וּמִצָּפ֖וֹן וְעַד־מִזְרָ֑ח יְשׁ֥וֹטְט֛וּ לְבַקֵּ֥שׁ אֶת־דְּבַר־יְהֹוָ֖ה וְלֹ֥א יִמְצָֽאוּ

I could go on and on.

And then there's Anthony Bourdain in Parts Unknown (2013) putting on tefillin at the Wailing Wall. His mother was Jewish. Go figure. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lxVibblcvjA

gershon hepner

RESPONSE TO THE WANDERING JEW’S SOLILOQUY

Were our primal parent’s errors not their own,

by God’s omniscient mind foredoomed, foreknown,

as Shelley claimed? Omniscience of God

is not a reason we should spare the rod

when people misbehave, since God’s foreknowledge

cannot, as great philosophers acknowledge,

act as an excuse for actions of the creatures

who, Genesis relates, share many features

that constitute the image that’s divine.

Once God created them He drew a line

between His knowledge and their misbehavior,

right conduct their sole duty and their savior.

Although He knows the future this does not

predestine actions that we should boycott,

and have the power so to do since we

possess a will he destined to be free.

Our primal parents wandered when they fell

from favor, but God sent them not to Hell,

where those who’ve never seen it say men burn,

but taught their children how they could return.

He showed them a divided road and made

two paths, both right, for neither He forebade:

one was repentance, one the right to wander,

seeking always what is far and yonder

rather than what’s right at hand. The choice

is one that makes the Jewish heart rejoice,

because it knows God’s wisdom does not force

the Jew to follow a predestined course.

This poem is a response to Shelley’s “Wandering Jew’s Soliloquy,” which is the last part of a poem “The Wandering Jew” which he wrote when he was 18 and was first published posthumously, in 1831. In the last six lines of his soliloquy the Wandering Jew cleverly blames God for the Fall of Adam and Eve. My poem points out that God’s foreknowledge does not cause predestination, acquitting mankind of their offenses.