The Living Waters of History

On a late Friday afternoon in 1432 Sevilla, a young converso girl named Amalia stops to wash off the ashes her mother has purposefully smeared on her to make her look dirty, before sending her out to the butcher. After throwing the pork sausages and ham she has bought into some tall grass, she begins to scrub herself in the natural spring her mother, a secret Jew, calls mayyim hayyim, “Living water,” though it makes the girl’s “fingers look as pale as the dead.” This finely crafted scene, rich with layered meaning, opens the latest historical novel by Laurel Corona, The Mapmaker’s Daughter. After whispering the Hebrew blessing recited upon washing one’s hands, Amalia, six, begins to clean off the grime.

When my hands are so clean they squeak, I splash water on my face to come home looking fresh for Shabbat. I imagine the sausage hidden in the grass, and since there is no blessing for throwing forbidden meat away, I whisper the words I often hear my mother say. “Please accept that we honor you the best we can.”

Corona has chosen to write the story of Amalia Riba in the first person present, a device that lends immediacy and emotional resonance to much of the story, but sometimes clangs with a disconcerting falseness. The book follows Amalia from her girlhood in Sevilla, across the kingdoms and duchies of Spain and Portugal, to Muslim-held Granada and on to Valencia in 1492 where, as an old woman, she is being chased out of Spain by the edict that expelled all Jews unwilling to convert.

Moving through the narrative with Amalia is a famous atlas, a copy of one made for the king of France at the behest of a Spanish monarch, for Amalia is not just a mapmaker’s daughter, but the granddaughter and great-granddaughter of mapmakers to royalty as well. Corona inserts Amalia into history as the grandchild of Jehudà Cresques, son of the atlas’ creator, who converted after the persecutions of 1391, changing his name to Jaume Riba. “It was too terrible a thought never to see our work again—may the Evil Eye not punish me for such pride—so we secretly made this copy, which we’ve kept all these years,” her grandfather Jaume tells her as they pore over the atlas one Sabbath afternoon. The atlas (which now resides in the National Library of France) serves as a touchstone for Amalia, a reminder of her roots, a guide to her future, appearing at intervals in the narrative, staying with her through the turns of plot and fate.

Corona’s Amalia is also anchored by her association with other famous figures of pre-exilic Spain, a tool that at times is enlightening, but more often than not so grandiose as to be a distraction. Amalia becomes a creature as fanciful as the mermaid that follows a ship in her grandfather’s atlas, serving as her father’s translator and aide at the court of Prince Henry the Navigator. Her father has, conveniently for the story, been struck deaf, and Amalia is felicitously gifted at languages, mastering Castilian, Latin, Arabic, Hebrew, and Portuguese by the time she is 10, in addition to inventing a system of signs she uses to communicate with her father.

If she had crossed paths with one or two names we know from our history books, it would have remained felicitous rather than forced. But Amalia catches the attention of one of Prince Henry’s most important captains, marries him, and bears him two children before a flick of Corona’s pen sends the captain to the watery deep, leaving his wealthy widow to return to her faith and raise her surviving daughter as a Jew. The family that takes her in, teaches her, and provides a husband for her daughter from their sons is none other than the illustrious Abravanel clan, Iberia’s most famous Jews. Leaving them, she becomes a tutor to two grandchildren of the Muslim caliph of Granada, and then to Isabella—the future Isabella I of Castile who would one day expel her and all her kind—via a childhood friendship at Henry’s court with the future queen’s mother.

Corona’s narrative whirlwind is as breathtaking as it is unbelievable. Are we to believe a Catholic queen would say to a converso-turned-Jew, “I can’t say I like what you’ve done, but it is up to God to judge, and no one here need know you were ever anything else”? Would the Abravanels, as urbane and educated as they were, have encouraged Amalia to undertake an intimate relationship with a Muslim, hampered as she is by a genuine Zoharic tradition that warns men who marry widows will die prematurely? Would a Muslim caliph hire a Jewish woman to tutor his grandson? Corona’s bravura tale begins to quake under the improbabilities and impossibilities.

In an interview printed alongside the book, Corona says, “These women existed, despite the fact that we must now invent them, and because they existed, I feel compelled to do what needs to be done so that their lives can be celebrated.” Amalia is certainly celebrated, then inflated, amplified, and magnified. The words of Simone de Beauvoir could easily be Amalia’s: “I am too intelligent, too demanding, and too resourceful for anyone to be able to take charge of me entirely.” Amalia lives within the “sisterhood” Gloria Steinem says every “woman who chooses to behave like a full human being” needs. With her sisterhood she faces down Tomás de Torquemada, taunting him with verses from the Psalms. With her sisterhood she adopts a converso child whose parents have been killed in the Inquisition and invents new immersion rituals to recognize bravery.

Such celebration speaks to our zeitgeist, but it undermines the real stories of the women of that time and place, whose risk-taking and courage have been described by Renée Levine Melammed in Heretics or Daughters of Israel?: The Crypto-Jewish Women of Castile. It belittles the strength it took to keep the laws of Moses when being caught meant unspeakable punishment; the strength it took to remain calm and loving, raising up the next generation of Jews to an indeterminate future; the strength it took to leave Spain for the long journey into the unknown. “The glory of a princess is on the inside,” say the words of the Psalms, or as Corona writes, “the best things must always remain the darkest secrets.” Corona has a real narrative gift, but her novel ultimately tells us more about the 21st-century market for historical fiction than history as it was actually lived by such women. That would require a very different historical imagination.

Suggested Reading

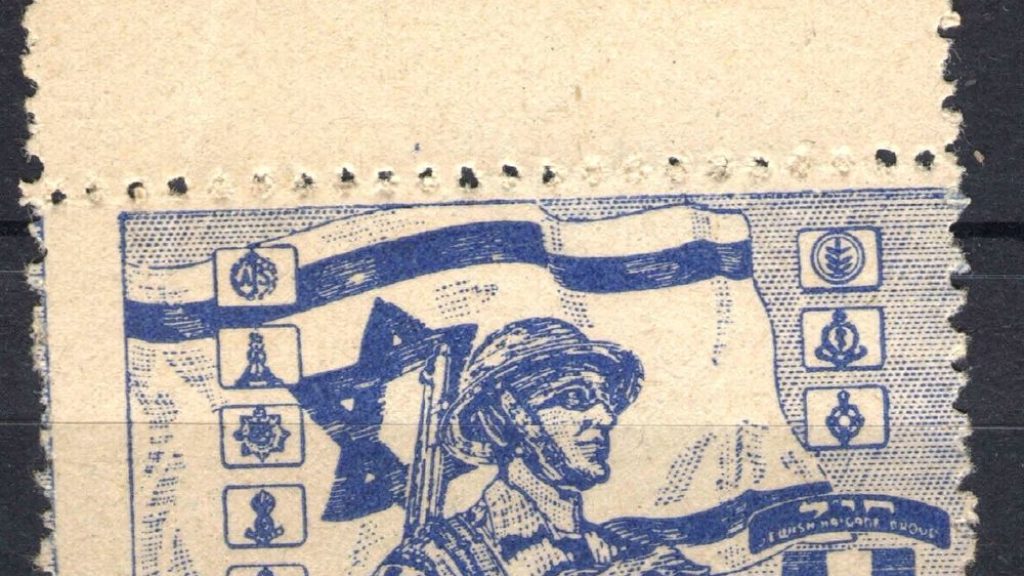

The Jewsraeli Century

Ben-Gurion declared that “with the creation of the state, we are standing on the edge of a new era. Not only in the life of the Jewish community in Israel, but . . . in the history of Judaism itself.” He was right, but not in the way he thought he would be.

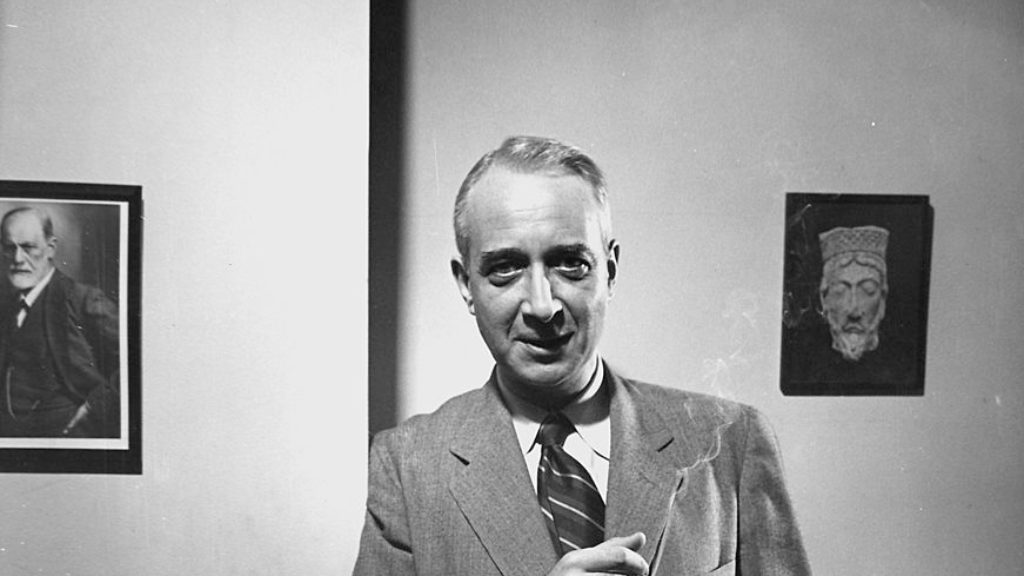

Man of Letters

Adam Kirsch’s judicious selection of Lionel Trilling’s letters throws instructive light on both Trilling’s life and American intellectual culture from the 1920s to the 1970s.

Rashi and the Crusader: A Legend

Did the great biblical and talmudic commentator meet Godfrey of Bouilon? A fascinating excerpt from Gedaliah ibn Yahya's Shalshelet ha-Kabbalah.

East Meets West

Following the Six-Day War, the East German government and the West German far left demonized Israel time and again, often vilely equating it with the worst thing in their own nation’s history: Nazism.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In