The Rothschilds of the East

“The Splendor of the Camondos” (La splendeur des Camondo) opened at the Musée d’art et d’histoire du Judaïsme in Paris (The Museum of the Art and History of Judaism, hereafter the MAHJ) in November 2009, and by the time it closed its doors this spring, it had been seen by an estimated 45,000 visitors. Le Figaro described it as an exhibition that succeeded in representing the artistic tastes and inclinations of an extraordinarily diverse family over the course of five generations. L’Express praised it for paying much-deserved homage to a family without any heirs and therefore in danger of being forgotten.

Those few who do recognize the name Camondo most readily associate it with the Nissim de Camondo Museum, named after a member of the family who was killed fighting for France in 1917. The museum is situated in the family mansion on rue Monceau in the eighth arrondissement of Paris, which his father Moïse donated to the city in 1935 in his son’s memory, together with the art they had amassed. The museum was opened to the public the following year, and remained open throughout World War II. It possesses one of the great collections of 18th-century French furniture, including such rarities as a table topped with petrified wood that was once owned by Marie Antoinette, an outstanding collection of Chinese porcelain, fine French paintings, and much else. But visitors to that museum are likely to receive only a glimpse of the evolution of the Camondo family and its Ottoman roots. This is the point of departure for the MAHJ exhibition and catalog, which draw upon the resources of a variety of museums and private collections in order to demonstrate the wide range of the Camondos’ interests.

Abraham-Salomon Camondo’s career set the stage for the rise of the family once known as “the Rothschilds of the East.” Born in Istanbul in 1781 into an already prominent financial family, he inherited the relatively modest banking establishment founded by his father in 1832. Abraham-Salomon had good connections at the sultan’s court, due in large part to his subventions to the Ottoman regime. He became a spokesperson for the Jewish community, intervening in its favor at times of unease and oppression by local authorities, as well as for Jews in trouble elsewhere in the Empire. When Moses Montefiore came to Constantinople in 1840 to obtain the sultan’s condemnation of the famous blood libel in Damascus, Abraham-Salomon was his host.

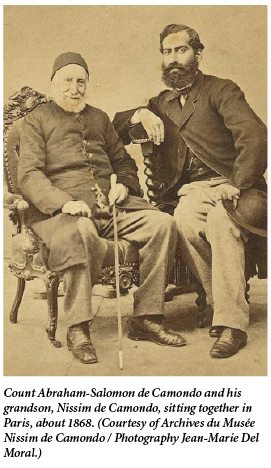

But Abraham-Salomon was more than an old-fashioned “Court Jew,” or shtadlan; he was an active agent of change. He helped to persuade the Ottoman government to grant the Alliance Israélite Universelle the right to set up a network of modern Jewish schools throughout the Empire, and fought to establish other, more modern institutions for Istanbul’s Jews, including hospitals and other health care facilities. Despite his modernism, Abraham-Salomon continued to wear traditional Ottoman dress throughout his life. He was described by a contemporary as having been “clothed in silks of different colors, occupying a throne furnished with cushions of purple and gold” on the Seder night in 1856. In a photograph dating from 1868 we see him still garbed in salvar (traditional Turkish pants) and caftan, sitting comfortably beside his grandson Nissim, who had by then adopted modern European dress. Abraham-Salomon stuck to his traditional language too; his business ledger from the 1840s, shown in the exhibit, is written in Ladino.

The Camondos’ modernism was tinged with a certain snobbery. At the same time that they fought against traditionalists in the community who were opposed to the Alliance’s activities, they lambasted the poor French of the Alsatian teachers who had come to teach in its schools. Their pronunciation, they complained, was “vicious.” In part, one assumes, to escape such insufferable provincialism, the extended family, which had a few years earlier received Italian nationality, decided to transfer en masse to Paris in 1869-70. This move brought with it not only cultural and aesthetic advantages, which were no doubt of especial importance to the younger generation, but political and economic benefits as well.

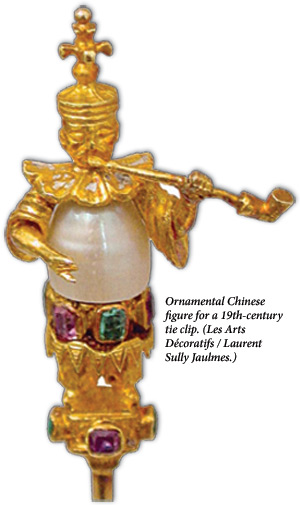

In Paris, the Camandos brought their bank into association with a local firm and settled into elegant living quarters, models of which appeared in the exhibition. It was in Paris too that several family members became passionate art collectors in ways that neither their Jewish nor their Ottoman backgrounds would have led one to expect. Newly arrived in the city and middle-aged, Nissim de Camondo, Abraham-Salomon’s grandson, developed a craving for extremely elaborate jewel-encrusted tie clips, created by leading Parisian jewelers. Many of them were gifts from his American-born mistress, the countess Alice de Lancy. While he undoubtedly made use of some of them, others were clearly intended only for his collector’s cabinet. One of the tie clips from the late 19th-century shows a Chinese man dressed in a traditional Chinese outfit and smoking a pipe. His face, hat, and pipe are made of gold, his body is composed entirely of pearls, and his dress is made out of emeralds and rubies encased in gold. Nissim’s son Moïse, who inherited his great fortune, loved 18th-century furniture and decorative arts, and went on to build his exquisite collection through connections with dealers and visits to auctions and galleries, where he encountered a world of antiquarians, some of the leading ones of Jewish origin—the Seligmann brothers, Wildenstein, and Kraemer.

Indeed, the world of art galleries, antiquarians, and auction houses of art had become an important avenue for the acculturation of Jews into the haute bourgeoisie in the 19th-century, and a profession that came to be synonymous with Jews (and accordingly maligned) in most major cities of western and central Europe. As his collection grew, Moïse became convinced of the need to have it concentrated in one place. The mansion which he built for this purpose in 1911 eventually became the Nissim de Camondo Museum. Although the MAHJ exhibit was lavish, it could only offer a fraction of these extensive holdings, elaborately displayed in the show’s catalog.

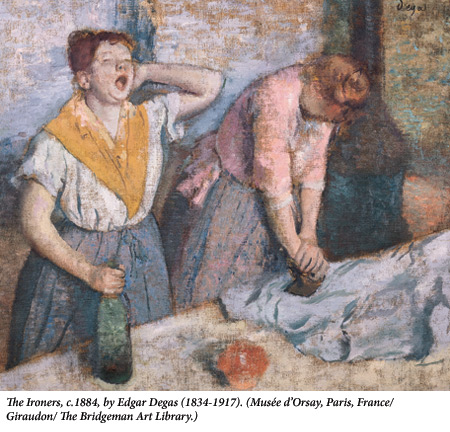

Moïse’s cousin, Isaac de Camondo, neglected finance almost entirely, while discovering the beauties of the arts. His passion for music was first excited by Wagner’s operas but in time he produced his own compositions of more popular orchestral and vocal music. He generously supported the development of new musical talent, musical magazines, and operatic productions in Paris. Isaac was also enthralled with the new impressionist paintings and Japanese prints, some of which appeared in the exhibition. Perhaps the fact that he was a Turkish immigrant helped Isaac ignore the conservative taste of the leading French art collectors as he assembled dozens of outstanding, and now universally acclaimed, works by Manet, Sisley, Degas, Monet, Cézanne and many others, building one of the finest private collections of Impressionist paintings. When he donated them to the Louvre, the curators described them as “horrific,” and kept them in the storerooms under lock and key until fashions changed. One of the more famous paintings exhibited, now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay, Degas’ The Ironers (1884-86), portrays two working-class women, one yawning broadly as she takes a break from her labor, and the other bent over, pressing her iron down hard on yet another shirt.As Isaac’s involvement in music and art intensified, he drew further and further away from the Jewish community and tradition. Significantly, neither he nor his cousin Moïse left any indication of having been disturbed by or engaged in the Dreyfus Affair, which roiled the Jewish community and French intellectuals in the 1890s. Their growing distance from things Jewish was clearly apparent. The heirloom Judaica they had brought with them to Paris—attractively shown in the exhibition and catalog—was dispersed in 1910 to a number of different recipients. Acculturation to the haute bourgeoisie had apparently been fully accomplished.

The MAHJ is situated in an attractive 17th-century mansion, known as the Hôtel de St. Aignan, located in the Marais district of Paris, a short walking distance from several museums, including the popular Pompidou Museum. After various alterations and divisions of the original mansion over the centuries, it served as home in the 20th-century for Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, several of whom were deported during World War II. Restored sensitively, the building was eventually offered to the Jewish community of Paris by Mayor Jacques Chirac in 1986 to serve as a museum of Jewish civilization. MAHJ was inaugurated twelve years later, with several floors dedicated to a permanent collection devoted to showing the history and artistic development of the Jews in France.

Walking through the exhibition, as it winds its way from the ground floor to the upper levels, one can see through the windows an adjacent wall of the former premises emblazoned with the names of the Jews who had lived there and been deported. The less than glorious past intervenes as one encounters the Camondo “splendors.” I was struck by a small stained-glass window from 1879 showing Count Abraham-Béhor de Camondo, a grandson of Abraham-Salomon, receiving the plans for his mansion, which was to include a private synagogue, from his architect. All of the figures appear in the window dressed in Renaissance attire. It reminded me of a fin de siècle painting by Anton von Werner. Von Werner was commissioned by the German-Jewish newspaper magnate Rudolf Mosse to paint a family banquet at which the Mosses and their guests are depicted in elaborate Renaissance clothing, enjoying a frolicsome and jovial dinner and merrily raising their goblets. Such partying was not uncommon in European high bourgeoisie circles at this time, but it has seldom been documented among Jews. Apparently, both Abraham-Béhor Camondo and the Mosse family entertained the fantasy of living in a Renaissance court.

Such 19th-century fantasies could not stand the harsh realities of the century to come. Nissim, who appears in several photographs proudly attired in his military uniform, was killed in battle in 1917. Other photographs depict his sister Beatrice, a passionate equestrian, dressed in riding apparel. Married to Léon Reinach, a scion of the distinguished family of financiers, politicians, and scholars, she converted to Catholicism in 1942, but was still sent to her death at Auschwitz, together with her husband and two children. Since Beatrice’s uncle Isaac had no legitimate offspring, the family’s name—and the family itself—disappeared. Its legacy and “splendor” remained only in those French museums that benefited years earlier from the munificence of the Camondos, and, of course, in the museum named after Nissim. The “Rothschilds of the East” failed to emulate the actual Rothschilds, whose descendants in various countries continue to pursue many of the goals and projects undertaken by their forefathers, both financial and philanthropic.

Splendor is the hallmark of the catalog. Bound in a gaudy gold cover, it offers helpful essays, pages and pages of excellent images of works by Manet, Monet, Degas, and many others, Japanese prints, Judaica, and exquisite French decorative arts and paintings, often with still more gold coloring in the background. What this volume cannot recreate, however, is the experience undergone by the museum visitor as he views the originals of the works it reproduces in a building where one is within sight of reminders of the Holocaust.

Holding this exhibition of “splendor” in such a building and bearing in mind the last, tragic stage of the Camondo family’s history, the curatorial staff of the museum had to decide how to incorporate the Holocaust. Wisely, the curators accorded it its due in the chronological evolution of the family’s saga, without allowing it to overtake the exhibition. Upon exiting, we see two large photographs of the Nissim de Camondo Museum. There, we are tacitly informed, lies the memory and true legacy of the Camondo family. Indeed, it also lies in the Louvre and several other museums.

Suggested Reading

Sephardi Soap

With the runaway success of the novel The Beauty Queen of Jerusalem, a television adaptation was all but inevitable, and the decision of Yes Studios to invest record amounts of cash in the show, while eyebrow raising, is also unsurprising.

One State?

Sari Nusseibeh's recent book is a new formulation of an old proposal.

In Giorgio Bassani’s Memory Garden

If you visit Ferrara, Italy, you can let Giorgio Bassani be your melancholy guide as you stroll along “the crowded rows of stores, shops and little outlets facing each other” to arrive at the synagogue’s “baked-red facade.”

A Moral Voice

Morality is the title of the last book Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks published in his lifetime. It was released in the United States in September, and he died in November at the age of 72.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In