A Moral Voice

A couple of years ago, my wife and I had the honor of having as our house-guests in Princeton Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory, and his wife, Elaine. The morning after their arrival, Rabbi Sacks and I were up early, ahead of our wives, and met in the kitchen. I, bleary-eyed, began making coffee. Jonathan, however, fully awake and alert, was eager for a serious conversation. “You recall,” he said, “what Hobbes says in the chapter on intellectual virtues?” I did, sort of, but it was early in the morning, and I was struggling with the coffee maker. “For the thoughts are to the desires as scouts and spies, to range abroad and find the way to the things desired,” he (accurately) recalled. “But it’s not like that is it?”

We agreed that Hobbes’s purely instrumental conception of practical reason—that is, the idea that what we ultimately want is a matter of brute desire, and the role of the intellect is merely to enable us to figure out how to get what we want—was seductive (especially in its simplicity) but wrong. We know that our lives are not like that. In the most important parts of our lives—love or learning, for instance—reason does not function simply as what Hume, following Hobbes, would describe as “the slave of the passions.” Sometimes we want things because, or in virtue, of our rational grasp of their intelligible value as intrinsically fulfilling and, as such, worthwhile. We grasp with our minds what fulfills us—what is objectively humanly good—as the complex (physical, rational, affective, relational, morally responsible) creatures we are, and we desire what is good precisely as aspects of our flourishing as human beings.

He noted that this is implicit in the biblical story of creation. Genesis tells us that human beings, though mere dust of the earth, are fashioned in the very image and likeness of the divine Creator and Ruler of all that is. Of course, we are not God. In fact, we are so far below him as to make his even noticing us a matter of wonderment. “What is man,” the psalmist asks, “that You have been mindful of him, mortal man that You have taken note of him?”

Yet, by God’s design, we are like God, albeit in limited and imperfect ways. By our God-given nature, we possess and come to exercise the Godlike capacities of reason and freedom—we are agents; God has given us a role—a certain sharing, in his creative power and activity. Like God, we can envisage states of affairs that do not (yet) exist, understand the point—the advantage, the value, the goodness—of bringing them into existence, and act freely on the reasons provided by our understanding. Such understanding is not merely a scout or spy to “find the way to the things desired.”

In virtue of our being made in the divine image, we are bearers of profound, inherent, and equal dignity. Even the poor, the weak, the vulnerable, the physically or cognitively disabled, the unloved, indeed the despised, the “defective,” the “useless,” the self-debased, the sinner, the dying, are of immeasurable value. Each is and, as a matter of strict moral obligation, must be regarded and treated as, in Immanuel Kant’s words, “an end and never as a means only.” That is why Jews and Christians were scandalized by infant sacrifice and are appalled today by the harvesting of transplantable vital organs from, say, severely cognitively disabled persons or even from convicted criminals, as is done in China. Any ideology that submerges the value of the individual person into the collectivity or sacrifices the dignity of the person on the altar of “the greatest good of the greatest number” stands condemned under the biblical standard of morality.

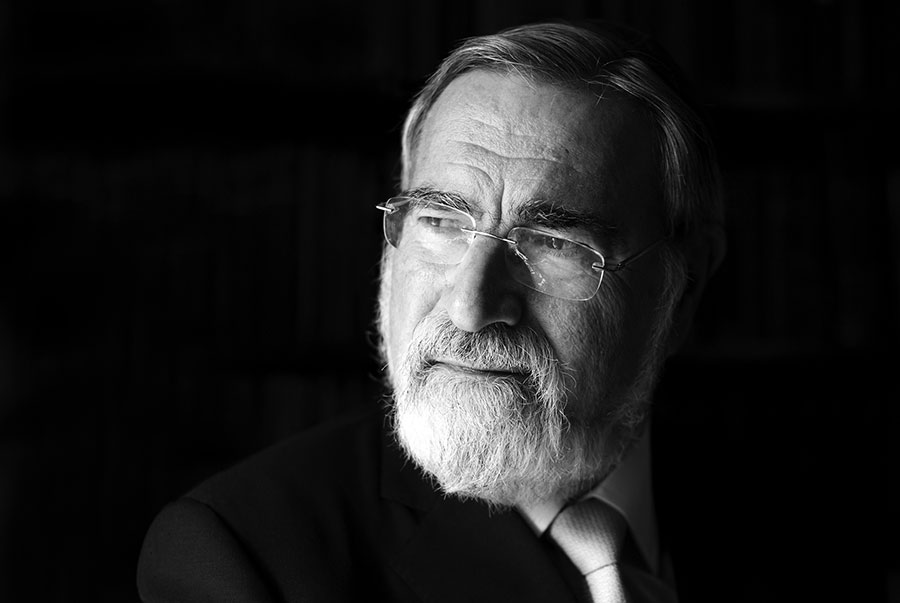

Morality is the title of the last book my beloved friend Jonathan Sacks published in his lifetime. It was released in the United States in September, and he died in November at age 72. Its subtitle is Restoring the Common Good in Divided Times, which brings us back to Hobbes’s mistake and Genesis’s depth. Rabbi Sacks’s argument was ultimately that a shared human nature means that there are certain basic aspects of human well-being and fulfillment that, when rightly understood, provide the basis for human solidarity. There is a common good because shared human goods provide reasons for human beings to cooperate in various forms of community, from families and communities of faith to national political communities and even the community of mankind. Some of the reasons people have to form bonds, relationships, and communities are not merely instrumental; for some communities—for example, the community of husband, wife, and children in marriage, or communities of faith—fulfill human beings in respect of the inherently relational aspects of our nature. This is a point that did not go unnoticed by the great Greek philosophers—consider, for example, Aristotle’s treatment in the Nicomachean Ethics of the inherent (and not merely instrumental) goodness of true friendship—but what really establishes it in the great civilizations of the West is the biblical witness.

Although Rabbi Sacks was a fine philosopher and a deep exegete, Morality is neither a work of moral philosophy nor a book of biblical interpretation. It is a defense of the Judeo-Christian worldview (a phrase and concept Rabbi Sacks did not hesitate to use) for the common reader, for whom the tenets of that tradition can no longer be presumed. At the same time, it is a response to and powerful critique of competing worldviews—the various forms of individualism, collectivism, and identitarianism—that vie in this era of extreme ideological partisanship and polarization to displace and succeed the biblical vision of morality.

A summary description of the argument Rabbi Sacks presents is that those of us living in modern Western societies and shaped by the ethos dominant within them have become fixated on the individual—on me, myself, and I—and the satisfaction of our own desires and attainment of our own goals. We have, to one degree or another, embraced the ideology of individualism. As a result, we have lost our sense of the importance of the common good—of we, ourselves, and us—and the value (and values) of the communities to which we belong and in which alone we can find our true fulfillment. We must move from what Sacks calls our “I society” back to a “We society.”

What Rabbi Sacks wants us to see is that we can avoid the errors of individualism and collectivism—and the trap of identity politics, which combines and feeds on the errors of both—if we correctly understand the nature of the human person. Individualism is false, teaches Rabbi Sacks (in line with the great tradition) because human beings, though packaged as individuals, flourish in significant part by virtue of intrinsically valuable—and not merely instrumentally useful—relationships with others, including by participating in communities, beginning with the family into which persons are born, whose value and dignity is indeed inherent. These are communities whose worth cannot be understood or accounted for purely by reference to services (or the quality of services) they provide. Among such communities are, as I noted, communities of faith. This is certainly the self-understanding of the Jewish community and of Christian communities too.

Man is indeed, as the Greek philosophers taught, a social animal. Still, individual human beings need others not merely for what others can provide—and they need relationships with others not merely for what they can “get out of” those relationships—but because aspects of the integral good of the human person are inherently and irreducibly social. Being a person is more than merely being an individual—for our fulfillment as human persons includes relationships with other persons that are worthwhile and desirable and desired just as such.

To some extent, of course, we need others for the instrumental benefits they provide, and neither Rabbi Sacks nor other thinkers in the Judeo-Christian tradition suppose otherwise. For example, we need the services of the auto mechanic, the doctor, and the lawyer. But our fulfillment also includes, and requires, our participation in noninstrumental forms of relationship—being a spouse, a friend, a parent or grandparent, a coreligionist—in which we love and are loved, in which we will the good of the other for the sake of the other and the other wills our good for our sake, in which we act together for the sake of goods that are not “mine” and “yours” but are truly ours—common goods and a common good.

Rabbi Sacks joins the distinguished Harvard political philosopher Michael Sandel in rejecting the idea that a human being is, or comes into the world as, an “unencumbered self.” Our connectedness to others, far from being an incidental fact about us, is integral to who we are. We enter life as someone’s son or daughter and grandson or granddaughter. Often we are born into communities of which our parents are, and perhaps our forebears were, members—including communities of faith. We will eventually make choices, including choices of relationships and communities to be part of. Still, we have unchosen relationships and unchosen obligations—including unchosen obligations we have in virtue of our membership in communities we did not choose to join.

To get where we need to be, we must understand that the dignity of the human person and the centrality of the common good are two sides of the same coin. This will require our embracing and exercising virtues of character as well as those of intellect and recognizing, as Sacks does, that they are never mere “scouts and spies, to range abroad and find the way to the things desired.”

Rabbi Sacks was not merely the leader of the relatively small Jewish community of the United Kingdom; he was, by virtue of his character, intellect, and eloquence, the leading spokesman for religious believers of all stripes—not only in the United Kingdom but throughout the world. He was simply head and shoulders above most religious leaders of his generation. He has his critics on both the Right and the Left, but I believe that his preeminence will be increasingly recognized in the coming years.

His stature as a moral leader comes through in several moments in this book. In one, he describes visiting a center for juvenile offenders while he was making a television documentary for the BBC on the state of the family:

They were all from broken, and many from abusive, families. When I tried to get them to talk about their childhoods, they refused to do so, out of loyalty to their families. So I changed the approach. I said, “One day you will have children. What kind of father would you like to be?” That is when they started crying. They said things like, “I’d be a tough father, but I’d make sure that there were rules, and whenever the children needed me, I would be there for them.” I found the experience deeply moving, and distressing. . . . I believe that the injustice done to them by society is hard to forgive. A generation imbibed the idea of sex without responsibility and fatherhood without commitment, as if there were no victims of that choice.

What one hears in these lines is not merely a man of empathy and insight but someone who has taken responsibility for his society and its failures—and tried through sermons, books, radio, and television to turn it back toward the common good.

I have said that Morality is a work of neither moral philosophy nor biblical interpretation, but Rabbi Sacks was a fine philosophical exegete, and, thankfully, sometimes he could not resist the urge. Toward the end of the book, he remarks that his doctoral supervisor, the great philosopher Bernard Williams, made an important distinction:

The most primitive experiences of shame are “connected with sight and being seen,” but . . . “guilt is rooted in hearing, the sound in oneself of the voice of judgement; it is the moral sentiment of the word.”

Sacks goes on to suggest that this explains the story of Adam and Eve, which, he says, is not about sex or forbidden fruit nor even original sin. “It is about the respective roles in the moral life of seeing and hearing.” The first reference to shame in the Bible, he notes, is that Adam and Eve were initially not ashamed of their nakedness. When the couple eats the forbidden fruit, their eyes are opened, and they seek to cover their nakedness out of shame. So far, Sacks notes, every element in the story is visual, but it is precisely at that point that a moral voice enters:

Far and away the most interesting line is the one that reads: “They heard God’s voice walking in the garden with the wind of the day. The man and his wife hid themselves from God among the trees of the garden” (Gen. 3:8). Everything about this verse is strange. Voices don’t walk. And you can’t hide from God.

Note, by the way, the unaffected lapidary brilliance of Sacks’s writing. Why, then, do Adam and Eve perceive God’s voice to be walking and imagine that they can hide from it? Sacks posits that they are still governed by sight and shame, but the Bible’s gift to the world is the moral voice. Sacks writes:

Judaism, with its belief in an invisible God who created the world with words, is an attempt to base the moral life on something other than public opinion, appearance, honor, and shame. As God tells Samuel, “The Lord does not look at the things people look at. People look at outward appearance, but the Lord looks at the heart.” (I Samuel 16:7)

As Rabbi Sacks understood, in a world obsessed with image and likes, retweets, and subtweets, this biblical message is as timely and vital as it ever was. How profoundly we will miss his wisdom and inimitable moral voice; thank God he left us his writings.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Chief Rabbi’s Achievement

Lord Jonathan Sacks is the most gifted expositor of Judaism in our day, and has written more than 20 books that are both learned and very accessible.

Religion and Power

Rabbi Sacks, who is in the end an optimistic thinker, sees a process of internecine violence leading to religious moderation happening within Islam now.

Is Repentance Possible?

And should we add a confession on Yom Kippur “for the sin of opening browser windows of distraction”? On Aristotle’s akrasia and Maimonides’s teshuvah.

Revisiting Herman Wouk’s City Boy

Remembering Herman Wouk's "gentle mockery at the shopworn pretensions of bohemian poseurs and ethnic Jews passing as nonhyphenated Americans."

Robert J. Bresler

Prof. George, Thank you for that superb article. In a time when religious thinking was taken seriously, this book would be a major event. -- reviewed and discussed everywhere. You would be the ideal person to organize a symposium of major scholars reflecting on Rabbi Saks' work.

Rob Bresler