In Giorgio Bassani’s Memory Garden

When, in August 1945, Geo Josz reappeared in Ferrara, the only survivor of the 183 members of the Jewish community whom the Germans had deported to Germany in the autumn of 1943, and all of whom were generally believed to have ended up in the gas chambers, no one in the city at first recognized him.”

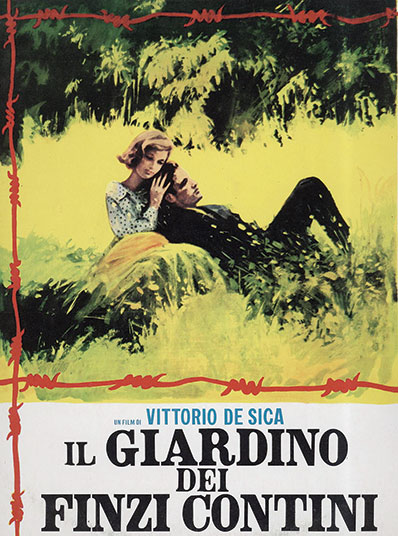

Thus begins the short story “A Memorial Tablet in Via Mazzini” by the Italian author Giorgio Bassani, who was best known for his 1962 novel The Garden of the Finzi-Continis (and the Oscar-winning Vittorio De Sica film based on it). Along with Primo Levi, Bassani was among the first writers to chronicle the fate of the Italian Jews under Mussolini and over the course of the Holocaust. Now Bassani’s complete magnum opus has reappeared in a new English translation by British poet Jamie McKendrick, published in a single volume under the title Bassani chose: The Novel of Ferrara.

Bassani set all six of the separate volumes that comprise his larger saga—the others are Within the Walls, The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles, Behind the Door, The Heron, and The Smell of Hay—in and around his native town of Ferrara, where Jews have lived since 1277. The city’s medieval walls and the streets of its one-time Jewish ghetto, still intact and visible today, provide physical metaphors for the boundaries that in the centuries before World War II separated the Jewish community from its Christian neighbors while also embracing its members within the shared borders.

Contemporary visitors to Ferrara can also see the actual memorial tablet on Via Mazzini, which was the main street of the former ghetto and, even after that, of the city’s Jewish community. If you visit Ferrara, as I did recently, you can let Bassani be your melancholy guide as you stroll along “the crowded rows of stores, shops and little outlets facing each other” to arrive at the synagogue’s “baked-red facade.” The stone plaques bearing the names of the Ferrarese Jews deported to extermination camps between 1943 and 1945 flank each side of the entrance to the synagogue, a palazzo that dates to the 15th century and whose interior Bassani describes in detail.

This very spot, at no. 95 Via Mazzini, is where, four months after the war’s end, Bassani has Geo Josz suddenly reappear among the living. But how could that be, the town wonders? His name is there for all to see, among the Jewish dead listed on the memorial plaque, and his concentration camp tattoo visibly testifies to where he has been. His clothes resemble a ragtag combination of the remains of concentration camp uniforms, making him look like a ghoulish clown. But rather than being emaciated, his body is weirdly bloated, as if “swollen with water, a kind of drowned man.”

And yet here he is, forcing the townspeople to remember him, even though they would prefer not to recall where, why, and how he and so many other Jews had disappeared. Geo reclaims the former family house that had not so long ago been seized and occupied by the fascist regime responsible for deporting his and the town’s other Jewish families. He compels his fellow Ferrarans to view the photos he has salvaged of the family members who were killed and listen to him recount the horrors of his life in the camps. His very insistence on remembering makes Geo intolerable to them, his survival an impediment to their postwar desire to put the past—including Geo’s past—behind them. Before long, the townspeople shun him, their faces “lit up with malice.” They cannot understand why he doesn’t get over the past and get on with life, as they are. They expel him from a town club and breathe a collective sigh of relief when Geo mysteriously disappears from Ferrara once again.

“A Memorial Tablet in Via Mazzini” was one of Bassani’s earliest short stories, written in the 1950s and included in Within the Walls, the first of his six books of fiction that make up The Novel of Ferrara. The last one, The Smell of Hay, appeared in 1972. Over the course of those years he had increasingly come to see these works as a unified whole. That led him to embark on what might be called a literal re-vision as he reworked the individual books to create his now epic The Novel of Ferrara. This unified edition appeared in 1974, but he was not yet done. He reworked it once more and brought out his final version in 1980, which is what Jamie McKendrick has now masterfully translated.

While free-standing as individual volumes, all six of Bassani’s books hang together thematically, just as his title suggests, as the story of Ferrara. Throughout, Bassani conjures a street map of Ferrara as vivid as it is precise. The city’s distinctive historic landmarks serve as the unchanging backdrop to personal dramas that play out over several decades, while this outward-seeming stability deepens the contrast to the dramatic political transformations that will upend the characters’ lives as the 1930s and 1940s progress. Wherever you go in these stories, Bassani brings you back to the town’s historic center, a spot from which you only need raise your eyes to see the city’s defining structure, the four crenellated towers of the fortress-like 14th-century Este Castle.

The effect of reading them one after another is immersive, carrying the reader to the years before, during, and after Mussolini’s rise to power. It is an epoch that encompasses two world wars and the Holocaust, all shown in microcosm within the walls and on the streets of Ferrara.

Bassani’s focus encompasses the inhabitants of the entire city of Ferrara: Christians as well as Jews, fascists and communists, members of the Resistance, and passive bystanders. We come to know his Jewish characters as they weigh their odds for survival, agonize over whether to escape or stay—and after the war, if they survive, whether to return. We also watch as his non-Jewish characters choose what they wish to see or ignore. He recounts all this with an abundant mixture of tenderness, intensity, and ferocity. Bassani’s prose invites an intimacy that makes it seem as if he is telling us his own life story. And in many ways, he is.

So many biographical details does Bassani share with the first-person narrator of the novels The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles, Behind the Door, and The Garden of the Finzi-Continis that it is difficult not to view the narrator as a fictional double. Born in the university city of Bologna in 1916, Bassani grew up in nearby Ferrara, where both sides of his family had lived for several generations. His father, a physician, had served as a medical officer in the Italian army during World War I; his mother had studied music and voice before marrying his father.

Even in the first years after Mussolini came to power in 1922, Jews experienced little or no anti-Semitic stigma. Many of Ferrara’s Jews, including Bassani’s father, were even proud members of Mussolini’s Fascist Party. The Jews of Ferrara considered themselves as thoroughly Italian as they were Jewish.

And so Bassani depicts Jewish families mingling easily—at least outwardly—with their non-Jewish friends, just as he and his family did: vacationing at the same resorts on the Adriatic Sea, playing tennis at the local sports clubs to which they all belong, and pursuing educational opportunities at public schools and universities that are open to all, regardless of religion.

He also shows the residual anti-Semitism hiding in plain sight even during such halcyon times and how easily it was brought to the fore. That warning pervades Behind the Door, set in the early 1930s. It’s the story of a schoolboy humiliation, but no less traumatic for that. In the narrative sweep of The Novel of Ferrara, it foreshadows the many blows to come.

Here the adolescent first-person narrator is introduced to casual anti-Semitism by two Christian schoolmates, one a wealthy aristocrat, the other an impoverished scamp. These two exist at opposite ends of Ferrara’s social spectrum, yet they agree on one thing, their baseline disgust for Jews. In a cruel prank, the narrator is manipulated into eavesdropping as his two supposed friends laughingly discuss their shared distaste in crude detail. The narrator burns with shame and rage at this pitiless betrayal of trust, but it is also a revelation, exposing the false sense of security and acceptance that Italian Jewry had been lulled into taking at face value.

By 1936–1937, the years in which The Gold-Rimmed Spectacles is set, the book’s narrator, like Bassani, has entered the university at nearby Bologna. Anti-Semitic propaganda has become common, and so have openly anti-Jewish remarks and behavior. Speculation abounds about the possibility of anti-Jewish legislation, with newspaper columns constantly referring to Italy’s “Israelite” problem. Gentile family acquaintances openly praise not only Mussolini but Hitler, and the narrator’s non-Jewish university friends begin distancing themselves from him.

Bassani dramatizes these changes in tandem with the story of Dr. Athos Fadigati, a respectable Christian physician in his late forties. As a closeted gay man he is an outsider whose secret has long been ignored by his many patients in return for his exceptional medical care. When his secret is exposed, he becomes a pariah. The question that hangs over the narrative is: Could a similar trajectory await the Jews?

It could, and it did, starting with the series of racial laws that began rolling out in September 1938. The laws banned the country’s 46,000 Jews from attending or teaching school; from civic service jobs and roles in politics, finance, and government; and from practicing law, medicine, journalism, and publishing, among other professions. They also expelled Jews from memberships in libraries and sports clubs, barred them from most hotels and restaurants, and allowed the confiscation of their homes, personal property, and businesses.

Bassani experienced these outrages himself and vividly depicts his characters’ shock and outrage as the privileges they had until so recently taken for granted are rescinded, one by one. “[W]e no longer belong to any class, we make up a social group apart, as in medieval times,” the recurring character Bruno Lattes bitterly laments.

In his life as in his fiction, Bassani had managed to receive his degree at the University of Bologna by virtue of a loophole; he had enrolled for his final year just before the racial laws went into effect. But unable to follow his wished-for career path as a teacher, he took instead the only educational job available to him as a Jew, which was teaching the Jewish students who had been expelled by the state schools—an alternative work path also chosen by the character Lattes.

Lattes, we eventually learn, manages to save himself by escaping to America, where he builds a successful academic career. But Bassani chose to remain in Italy, soon joining the anti-fascist Resistance. In 1943, he was imprisoned for three months, after which he went into hiding until the end of the war. (The prison building where he served his sentence now houses the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah.)

The Holocaust shadows all six books of The Novel of Ferrara, but especially The Garden of the Finzi-Continis. It is the most fully realized and resonant of the individual volumes and deserves its place at the very center of The Novel of Ferrara.

At its heart lies the friendship and unrequited love of the narrator for Micòl, whom we know from the novel’s very first pages will not survive the Holocaust. The narrator begins his reminiscence when a visit to ancient Etruscan tombs sparks his memory of another once grand but now abandoned monumental tomb built to provide eternal repose for deceased members of the aristocratic Jewish Finzi-Contini family of Ferrara. In 1943, they had been deported to Germany, “and no one knows whether they have any grave at all.”

Even before the war, the narrator tells us, the flamboyant tomb was regarded by Ferrara’s Jews and non-Jews alike as an aesthetic “monstrosity” aimed at separating and elevating the family in death. Similarly, their elegant mansion and its vast garden isolated them from the lives around them, and so old or ill are some members of the family that they seem to have cut themselves off from life altogether.

De Biasi/Mondadori Portfolio via Getty Images.)

But the wealth and prestige of the family lent them a dual aura of mystery and enviability. One day in 1929, when he is in ninth grade, the narrator accidentally wanders into the lushly wooded garden after school and falls asleep. He awakens from his nap as into a real-life dream when he hears Micòl calling him from afar. She has climbed to the top of a ladder on her side of the garden wall, and from there she invites him to climb up his side to join her. But he is not quick enough, and she disappears.

It turns out that though the two have never been formally introduced; they know each other as fellow members of Ferrara’s Jewish community. But what does such a bond actually mean, the narrator wonders?

What, after all, did that word “Jewish” mean? What sense could expressions such as “The Jewish community” or “The Jewish Faith” possibly have, for us, seeing that they entirely left aside the existence of a far greater intimacy, a secret one, to be valued only by those who shared it, which derived from the fact that our two families, not by choice, but by virtue of a tradition more ancient than any possible memory, belonged to the same religious observance.

Possible answers are suggested as the story jumps forward to 1938, two months after the racial laws have gone into effect. The narrator, along with all other Jews, has been banned from the city’s public tennis club, and Micòl’s older brother Alberto invites them to use the clay court at the Finzi-Contini estate. There the group convenes their own club, as it were, with games of tennis the backdrop for flirtation and friendship. As parks, piazzas, and other public places become off-limits to Jews, the elegant snacks provided by the Finzi-Contini staff also serve as an alternative café where the group can sit and chat as they used to. When the narrator is unceremoniously told to leave the town’s library—“a place I’d hung around since my school days and where I always felt at home”—Micòl and Alberto’s father invites him to use his extensive personal library instead, where he finds all the resources to complete the writing of his university thesis.

The self-sufficient Finzi-Contini compound becomes a shared ghetto for the outcasts. The estate, with its alluring garden, promises security from the world outside. But this imagined assurance against harm, whether from within or without, is illusory. When Micòl rejects the narrator’s romantic overtures, he exiles himself from the Finzi-Contini estate, never to see her or her family again.

After the war, only the decaying tomb remains, as well as the narrator’s memory of the garden that, for all its beauty and all its owner’s wealth and prestige, had no power to defend or magic to save them. The expulsion from the garden is complete, and so is the wreckage of a family and a culture.

Bassani’s monumental elegy to the city’s doomed Jewish community restores the dignity that it is owed even as it compels us to relive the devastation endured.

Suggested Reading

The Hands of Others

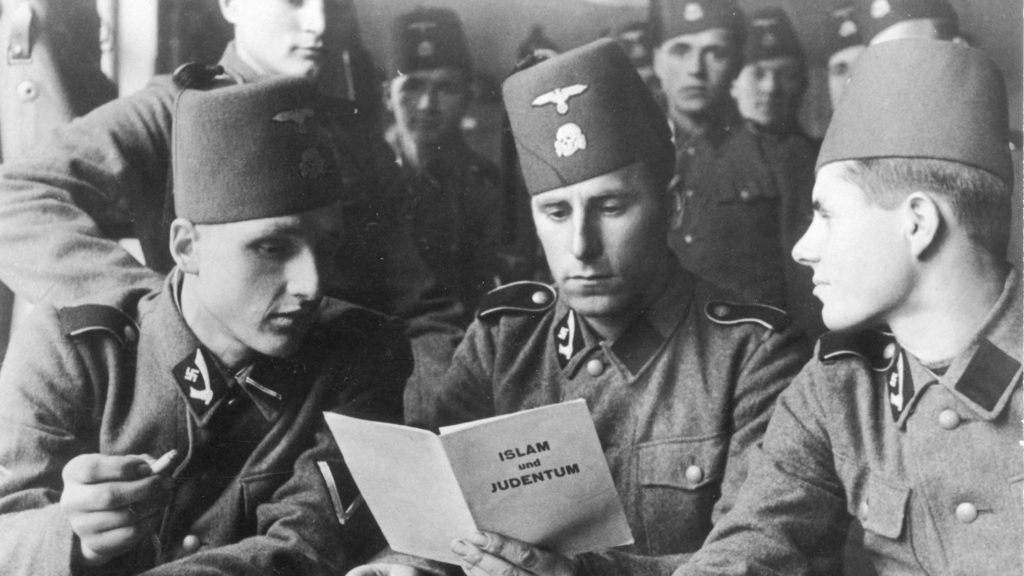

Many people know of Mufti al-Husseini's SS activities. But how many Arabs shared his admiration for Hitler and attraction to Nazism?

What’s Love Got to Do with It?

Shai Held measures up the sprawling mass of Jewish tradition and claims, against incredulous critics going back to Saint Paul, that love has a great deal to do with it.

Historical Agency

Among the many papers discovered in the Cairo Geniza are documents, including letters between Yeshua ben Ismail of Alexandria and Khalluf ben Musa in Qayrawan, in present-day Tunisia. The papers showing disintegration of their partnership shine a light on how a particular kind of business agreement affected the composition of a halakhic guidebook still widely consulted to this day.

On Re-Reading a Banned Book: Nathan Kamenetsky’s Making of a Godol

Rabbi Nathan Kamenetsky spent years on an odd, brilliant biography of his father. The book was banned, and one leading haredi rosh yeshiva said he had forfeited his share in the world to come. Now it is an underground classic that costs $2,503 on Amazon.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In