Unfinished Rock

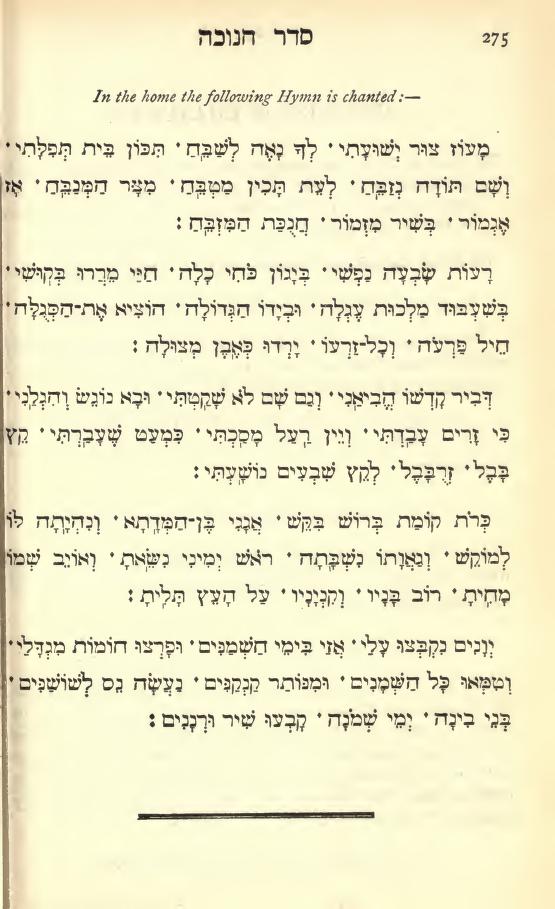

Imagine a Hallmark movie called A Very Teaneck Hanukkah: a large, wholesome family dressed in their best sweaters huddles around a lit menorah singing “Ma’oz Tzur”—the most recognizable and ubiquitous of Hanukkah songs. Or, at least, they quickly sing the first stanza so that they can exchange gifts and sit down to eat the holiday’s traditional oil-fried cuisine.

Yet one stubborn cousin insists that the latkes wait until the family stammer through all six stanzas of this song about salvation from our foes. In the first stanza, the poet praises God, the eponymous Ma’oz Tzur (or Rock of Ages, if you will) and prays that he restore the Jerusalem Temple so that the poet and singer can “finish, with song and psalm, the altar’s dedication.”

From there, a litany of Jewish troubles is laid out over four stanzas in a boppy tune that’s been sung for hundreds of years. First there were the Egyptians and Pharaoh, whose army God “sank like a stone in the deep.” Then came the Babylonians, who took us from the Holy Temple and oppressed us for seventy years. The Persians were next, led by Haman the Agagite, who “sought to cut down” Israel, “the tall fir tree.” Finally the Greeks, enemy of the Hanukkah story, attacked, “defiled the oils” of the Temple,” and a miracle was performed so that “the last remaining flask” lasted eight days. Therefore, the Sages instituted the holiday of Hannukah. Let’s eat!

Not just yet. Most often, the stanza stickler will make everyone sing through several more lines in which the poet leaves behind the description of past events, turns to his present, and shifts from the first person to the second, beseeching God to “bare his holy arm, and hasten the time of salvation” as “the hour has been too long delayed, there seems no end to the evil days.” Thus, the poem that began with a plea that God restore the Temple concludes with a plea that he end the Exile, and the harsh rule of European Christians over Jews. Sandwiched in between are four cases in which God already saved the Jewish people, as if to argue, “Why not save us again?”

Finally, everyone can eat, but a long-debated question remains about the final verse: was it originally part of the hymn? We don’t know much about the medieval Ashkenazi poet who wrote Ma’oz Tzur, but the start of the first five stanzas spells out his name in an acrostic: “Mordechai,” which may be a sign that the original poem was not six stanzas.

While today one would be hard-pressed to find a siddur that omits Ma’oz Tzur’s final stanza, this was not always the case, as the scholar Gabriel Wasserman has shown. Even some siddurim published in the twentieth century lack the sixth stanza and it does not appear in any manuscript or early printed edition of the poem until the eighteenth century, when it was published in the Kitzur ha-Shela”h, a book written by the Sabbatian Michel Epstein. So it seems likely that the last stanza is a later addition, written by Epstein or, at any rate, someone other than the medieval Mordechai.

On the other hand, is it possible that previous Jewish scribes, fearful of the repercussions of singing songs that ask God to smite only Christian rulers, excised the final stanza of Ma’oz Tzur, which Epstein restored? If so, the manuscript and printed evidence would still be difficult to explain: how did an eighteenth-century Sabbatian learn of the lost last stanza? This suggests that the poem may have originally ended with the stanza concerning the Greeks and the miracle of Hanukkah, which, of course, would make sense for a Hanukkah song.

Scholars who favor the theory that Mordechai wrote the sixth stanza point to the thematic consistency of the entire poem. Moreover, while Mordechai’s name is fully spelled out by the fifth stanza, the sixth stanza begins with the letter het. Then its second and third words each begin, respectively, with the letters zayin and qof, thus spelling out the word “hazaq”—strong—a word medieval Hebrew poets often acrostically appended to their names.

The final stanza is also written in the same poetic style of those that preceded it. It echoes the traditional Jewish historical paradigm, which knows of four eras of gentile domination (usually beginning with the Babylonians, though Ma’oz Tzur adds the Egyptians to the scheme), concluding with either Christian or Muslim rule. As noted, the final, dense lines of Ma’oz Tzur deal with the then-current crisis of Christian rule, “the evil nation,” and, as Yitzhak Y. Melamed has argued, the stanza even goes as far as asking God to “bring the end of Christianity,” thereby concluding the historical arc of the poem.

So, what are we to do with lines of a poem that fit thematically but lack a historical paper trail?

I think that the solution to this puzzle may lie not in the final verses of the poem, but in the beginning. In the first stanza Mordechai writes in the second person and beseeches God to rebuild the Temple. Looking forward to that moment, the poet declaims that “it is then that he will finish with song and psalm,” the dedication of the altar. But this line can also be read as a metapoetic comment, in which Mordechai is referring not only to the incomplete nature of the Temple’s past dedication, celebrated on Hanukkah, but also to the unfinishedness of his own poem.

In other words, Mordechai wrote a poem that is intentionally missing a final stanza. In this reading, Mordechai left out a concluding stanza for it is only at that future time, when God ends the exile, that the poet can return to finish the poem. He couldn’t write a stanza on Christianity—not because of the fear of censorship (though that may also be true), but primarily because, unlike the prior historical periods, this one is not yet over. Christian rule is still ever-present, the exile is ongoing, and Jewish history, like the poem, remains unfulfilled.

If we subtract the questionable final stanza, Ma’oz Tzur moves from being a harsh critique of Christianity to being a poignant comment on Exile. In Exile, not only is history unfinished, but so is poetry. Az egmor, bi-shir mizmor—one day, the song will be complete, and we can all eat our latkes in peace.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Lost Music

Jeffrey M. Green, Aharon Appelfeld’s translator for more than 30 years, remembers the beloved Israeli novelist.

In (Partial) Defense of Doublethink

How does one survive psychologically under the control of chaotic evil? Take Evgenia Ginszburg, for example . . .

The Exilarch’s Lost Princess

In real life, or as much of it as historians can reconstruct, Septimania was a name for the region of southern France that included the Jewish populations of such venerable cities as Carcassonne, Narbonne, and Toulouse. Jonathan Levi leans on the most delightfully far-fetched version of these events in his latest novel.

Friendship in the Fields of Moab

Naomi and Ruth have mourned together and are now setting off on the 50-mile journey from the plains of Moab to Bethlehem, toward an uncertain future—alone but side by side.

Menachem Kagan

Prof. Landes,

I really enjoyed your article about Maos Tzur. Even more obscure than the last stanza is ANOTHER last stanza. I first came across it in a Chanukah guidebook put out by the Koidenover Rebbe (they were a small Chassidus before World War One and are being revived by the current Rebbe in Bnei Brak). My father gave them some money and they sent it to me. This siddur (it's not really a siddur, it has Tefilos for Chanukah and some laws and since it is Chassidik stories too!) has another Stanza. The siddur says it originated from the Rema. Indeed, I have a very comprehensive Zemiros and for Shabbos Chanukah they have Maos Tzur. The footnote includes the added stanza of the Rema. I would love to send it to you for your review but there was no way I could attach it to this comment section.

Enjoy!

Menachem Kagan

Woodmere, NY

917-434-5768