Kidnapped!

Shortly after Isser Harel engineered the abduction of Adolf Eichmann in Argentina, the legendary director of the Mossad was involved in another kidnapping—two in fact. The first victim was a young Israeli boy named Yosef (“Yossele”) Schumacher, whose ultra-Orthodox grandparents had refused to return him to his parents, whom they regarded as insufficiently religious. Eventually, they spirited him away in defiance of a court order to send the boy home. Yossele’s disappearance in February 1960 roiled Israel, but two years passed and the police still hadn’t located the boy. Finally, Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion put Harel on the case.

Even for the Mossad, locating Yossele was a tough job. For one thing, the agency was startlingly short on agents who knew Yiddish. Nevertheless, Harel quickly learned enough to conclude that the boy was no longer in Israel. Leaving all other Mossad business in the hands of a deputy, he flew to Paris to coordinate Operation Gur (Lion Cub). Two months later Harel’s team was exhausted and frustrated until an agent who had penetrated the haredi community in Antwerp finally came up with the intelligence that broke the case open.

The tip was about a French convert to Judaism named Ruth Ben David. Born and christened in northern France in 1920 as Madeleine Lucette Ferraille, she had moved to Paris with her family at age three. In his exhaustively researched and eye-opening biography, Motti Inbari tells us probably everything that can be known about her childhood, her parents’ divorce, her gradual abandonment of Catholicism, and her first unhappy and very brief marriage just as World War II began to a handsome but somewhat hapless young man named Henri Baud, with whom she had a son.

Lucette wanted more out of life than was within easy reach—more, indeed, than the Vichy regime encouraged. By 1943 she was divorced, with a BA from the University of Toulouse. That year, she also helped a female Jewish refugee escape deportation and certain death. Recruited by the Resistance in early 1944, Lucette, who was beautiful as well as brilliant, made her way into the heart of the local Gestapo by becoming the mistress of a Waffen-SS officer. Unfortunately, Inbari cannot give a detailed account of her exploits at this time, but he does refute accusations that she was a Nazi collaborator, quoting reliable testimony that while undercover she was in continuous contact with the Resistance and performed a “great service to the network, despite the delicate situation of her district.”

Afer the war, Lucette fell into a deep depression and found that neither Christianity nor philosophy could help lift her out of it. “It was Judaism,” she later wrote, “which met my sense of universalism, my concept of unity, my need for a convincing theology, and, above all, an increasingly strong inner calling.” In 1950 visiting Israeli academic named Ephraim Harpaz invited her to come to Israel and marry him. She loved Israel, but she didn’t marry Harpaz. Instead, she returned to France, where she converted to Judaism under the auspices of a Reform rabbi and adopted the name of Ruth Ben David.

Having become active in the Consistoire, the umbrella organization of French Jewry, Ben David met and befriended an Orthodox rabbi from Alsace, who—we should not be surprised to learn—wanted to marry her. The news that their rabbi was going to marry a convert with a somewhat checkered history upset his community, despite her decision to undergo a second, Orthodox conversion.

Ruth had other problems as well. In 1948, she had been involved in a somewhat shady small-scale import-export enterprise, which had led to her expulsion from Switzerland, but it was only in 1952 that she got into more serious trouble, when French authorities accused her and her partner in another import-export business of tax evasion. Inbari seems prepared to follow Ruth in laying the real blame for the crime on her partner, a stateless Holocaust survivor who successfully begged her not to incriminate him. Her fiancé seems to have been unfazed by all of this but eventually backed out of the marriage in 1953.

The couple had taken steps toward settling in Israel, but when their wedding plans collapsed, Ruth placed her son, Uriel (formerly Claude), in a religious Zionist boarding school and returned to France. By the time she returned to Israel in 1954, she had come to believe that “Zionism as a national movement could not meet her spiritual needs”—or those of her son, for that matter. She brought him back to France and installed him in a haredi yeshiva in Aix-les-Bains. Spending her summer vacations nearby, and studying at the institution herself, she “found, in this environment, brotherhood, equality and peace of mind, [and] complete observance of the Mitzvot.”

In 1959, Uriel decided to move back to Israel, and Ruth followed him. There she reconnected with Avraham Elijah Maizes, a haredi rabbi with whom she had studied in France. Now ensconced in Meah Shearim and affiliated with the radical anti-Zionist Neturei Karta movement, Maizes was close to Yossele Schumacher’s maternal grandparents. One day he came to Ruth with an urgent plea:

“Listen,” he said. “There is a great Mitzvah before you, and as I see it, only you can carry this through. It is Yossele Schumacher. Take this child and get him out of the country quickly. I am afraid we cannot do it much longer here. The salvation of a Jewish soul is at stake here—a world on its own. This is your job, go and do it, and G-d will be with you.”

Repeating the calumny that the boys’ parents had been trying not merely to regain their son but to take him back to the Soviet Union, Maizes virtually ordered Ruth: “You must get the child out of Israel!”

In no time at all, the former Resistance agent had worked out a complicated plot involving her son, disguises, and doctored passports that would land Yossele—who had been won over by his captors—in a yeshiva in Switzerland:

On June 21, 1960, Yossele, dressed up as “Claudine,” together with Ruth, took a taxi to the airport. . . . Ruth instructed “Claudine” not to look at people in the eyes. She passed through the security checks with her “daughter” without any difficulties. They boarded a plane and took off: “I knew that Yossele was flying to freedom.”

But this was just the beginning. Ben David came up with new plans and strategies to stay ahead of the Israeli authorities, eventually placing the boy with a host family in Brooklyn.

She couldn’t cover her tracks forever, though, and Harel, armed with the report obtained from the Mossad agent in Antwerp and other corroborating information, decided to kidnap Ben David in mid-June 1962 in Paris. Harel himself conducted the interrogation, unsuccessfully at first, but when Uriel was brought in for questioning in Israel, he spilled so many beans that Ben David’s position became hopeless. Inbari’s dramatic description of the climax of the interrogation is worth quoting in full:

Harel told her that he wanted to make a deal with her, and he read Uriel’s confession. When she heard it, she almost collapsed. Harel said that Uriel was at the center of events in Israel and that he came to conclude that the Yossele affair must be resolved immediately and without delay. Uriel made a deal that he and his mother would not be persecuted as long as she told them where Yossele was being held; if she failed to do so, she would have to pay the full price of kidnapping, smuggling, and concealing the boy, and so would her son.

Ruth was very upset. She struggled with herself: “I was surrounded, caged, with barbed wire cutting into my flesh.” She asked, “How can I know who you are and that you can speak in the name of the government?” Harel knew it was a onetime opportunity, so he pulled out his real diplomatic passport, with his real name, and handed it to Ruth. The people in the room were astonished. Ruth was held illegally in a foreign country, and Harel had just identified himself by his real name and title.

Ruth looked carefully at the passport, and after a while, she said in a voice choked with tears: “Yossele is at 126 Penn Street, Brooklyn, New York, with the Zangwill Gertner family. His name is Yankele.” Harel shook her hand and promised that she and her son would be free once the boy was in his hands.

After the FBI found the boy, Harel kept his promise. Ben David was allowed to resettle in Israel, and no charges were brought against her, Uriel, or, for that matter, anyone else involved in the kidnapping. Inbari argues, convincingly, that the state’s “initial strict response combined with postfactum forgiveness” was the right approach, “since the ultra-Orthodox community has almost never repeated similar criminal behavior.”

When Ruth finally returned to Israel about a year later, she was greeted as a hero by the members of Neturei Karta and met the group’s recently widowed leader, Rabbi Amram Blau. Within a few weeks the rabbi’s emissaries offered her his hand in marriage. She immediately accepted—and then learned his conditions: “Ruth would have to change her tights from beige to black, the color worn by all the women in Blau’s circle in Meah Shearim, and she must change her head cover from a colorful one to a black one.”

The new modesty requirements were, however, the least of her problems. Several of Amram’s children protested. The leadership of HaEdah HaCharedit, the ultra-Orthodox umbrella organization to which Neturei Karta belonged, forbade the marriage because of the twenty-year age gap between the two, the groom’s apparent sterility (hence the marriage’s pointlessness), and the fact that Ruth was a convert. The Satmar Rebbe, Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, offered her twenty-five thousand Israeli pounds as compensation for breaking the engagement. Ben David didn’t accept the deal, and she didn’t back down.

In response to gossip that she was insufficiently modest, she counterattacked:

She told Amram that her son, Uriel, had followed his children and noticed that Zippora, his grandson’s wife, wore tight clothes and did not have black stockings. Another granddaughter was wearing a modern suit, so that on sitting the skirt rises.

She dismissed the authority of HaEdah HaCharedit and went to New York to confront the Satmar Rebbe directly. Rabbi Teitelbaum “told her that he believed that the match would not be suitable for her due to Amram’s sins; his wife, Alte Feige, added that Amram was ‘a bum,’” and a poor one at that. Ruth, in turn, “accused Teitelbaum of perverting the truth in order to bring peace and tranquility among all the groups of Jerusalem.” And she told Feige that she would work for a living, and in any case, she “did not value wealth as American Jews do.”

In a follow-up letter to Teitelbaum, she said that when she learned the court ordered her not to marry Amram because she was too young for him, she couldn’t sleep or hold down her food:

Is being young a crime, she bitterly asked. Having said that, she understood that older men do not have the physical powers of young men, and from a sexual point of view, this can be a health danger if an older man cannot control his sexual desires. However, she assured Teitelbaum, her groom was a Torah scholar and a servant of God, and he never lived for material things.

She also had to refute the unfounded rumor, repeated in the press and by Blau’s children, that she had been a stripper in Paris during the war. Inbari writes that “one journalist even added . . . that an ultra-Orthodox rabbi testified he saw her stripping with his own eyes”—and then points out the unlikelihood of such a rabbi attending a strip club in Nazi-occupied Paris. He also suggests that the rumor may have been the fruit of a disinformation campaign that originated with Harel.

Meanwhile, Amram had convinced his children to retract their opposition and published a self-justificatory pamphlet in which he pointed out that in the Bible, Joshua, Boaz, and David had all married converts. As for the age gap—why Boaz was eighty and Ruth was only forty when they married!

However, the couple still needed Rabbi Teitelbaum’s permission to marry. In the summer of 1965, he granted it, on two conditions. In view of the ruling of the Jerusalem rabbinic court of HaEdah HaCharedit, the wedding would have to take place outside its jurisdiction, and the couple would have to live outside of Jerusalem, at least for a while. They were married in Bnei Brak that fall and eventually allowed to return to Jerusalem on the condition that Rabbi Blau relinquish his leadership of Neturei Karta.

They did not live happily ever after. As Inbari shows, Ruth Blau underwent fertility treatments in the hopes of having a child with Amram. He did not share her hopes and did not seek treatment, despite promising to do so. This infuriated Ruth, who even left him for a time, returning to France. However, she eventually came to terms with her disappointment and undertook an active role as a traditional rebbetzin, making matches and raising funds for yeshivot and seminaries, particularly those serving underprivileged boys and girls of non-Ashkenazi origin. But Ruth’s days of international intrigue were not over.

In January 1979, after the Shah had fled Iran but before the Ayatollah Khomeini had returned to the country, she wrangled a meeting with Khomeini in Paris and got him to promise that he would not punish Iranian Jews for Israel’s mistakes. Leaders of Neturei Karta are infamous for courting Israel’s enemies, but Inbari presents evidence from a former Israeli spy named Ari Ben-Menashe that something more may have been going on. Khomeini, it seems, may have met with Blau because she was covertly representing the Israeli government. The message that Khomeini apparently delivered to Prime Minister Begin was a slightly reassuring one: “Don’t worry Israel. First, my agenda is to deal with my Arab enemies. Then, I will deal with Israel.”

Inbari also reports Ben-Menashe’s claim that Ruth met with Khomeini in Tehran in September 1979, at Begin’s behest, to propose an arms deal with Israel in exchange for the release of the American hostages. He is not fully convinced that this actually happened, but he does find it plausible that she did so, even coordinating her moves with the Mossad, the organization that had once held her hostage.

The next year she traveled to Iran three times in an effort to save the life of Albert Danielpour, a wealthy Iranian Jew who was accused of being an Israeli and CIA asset. Danielpour had been sentenced to death by the Islamic Revolutionary Court in Tehran and then had his sentence briefly commuted, before being executed, despite Blau’s efforts. Later she would head to Beirut to try to save the lives of Lebanese Jews held by Iranian-backed militias. Again, she was unsuccessful.

In her eagerness to help Jews in Muslim lands, Ruth went further than one might have thought an anti-Zionist could go. When Yona Baumel, the father of one of three Israeli soldiers who went missing in a battle on the Lebanese-Syrian border in 1982, asked her to help find his son and the others, she was initially reluctant to get involved:

“At first,” [Baumel] said, “it was a dialogue of the deaf. She asked me to curse the Israeli government, but I refused. Eventually, she agreed to help. She traveled to Jordan with her French passport, and from there she reached Damascus, the capital of Syria.”

As Inbari observes, Ruth “agreed to help based on the halachic commandment to rescue prisoners but did not want anyone to think she was working for the State of Israel or assisting the IDF in any way.”

She didn’t succeed here either, but Baumel remained grateful nonetheless, as did a lot of other people. Although Blau was for a long time villainized by the Israeli press, mainly for her role in the Yossele affair, by the 1980s, Inbari writes, “the media developed a fascination with her” and the “Israeli public learned to accept Ruth as unique and eccentric and a legitimate part of Israeli society.” Her most irreconcilable opponent, the grown-up Yossele, never forgave her. But in the summer of 2021, more than twenty years after her death, her descendants publicly apologized for her actions, and “he accepted their remorse.”

Inbari, too, is generous in his overall assessment of the woman whose story he has so skillfully recounted. He recognizes her fanaticism and flaws but admires her resourcefulness, her courage, and her adherence to her principles. He ends his gripping tale with the assertion that Ruth Blau “atoned for her sins in the way she came to the help of Jewish prisoners in Lebanon and Iran”—though one can only wonder whether she herself saw things this way.

Suggested Reading

Satmar, American-Style

The explosive growth of Satmar Hasidim has shocked and worried many who see their culture as un-American. But two new books argue it was only in America that the sect could have flourished at all.

Kidnapping History

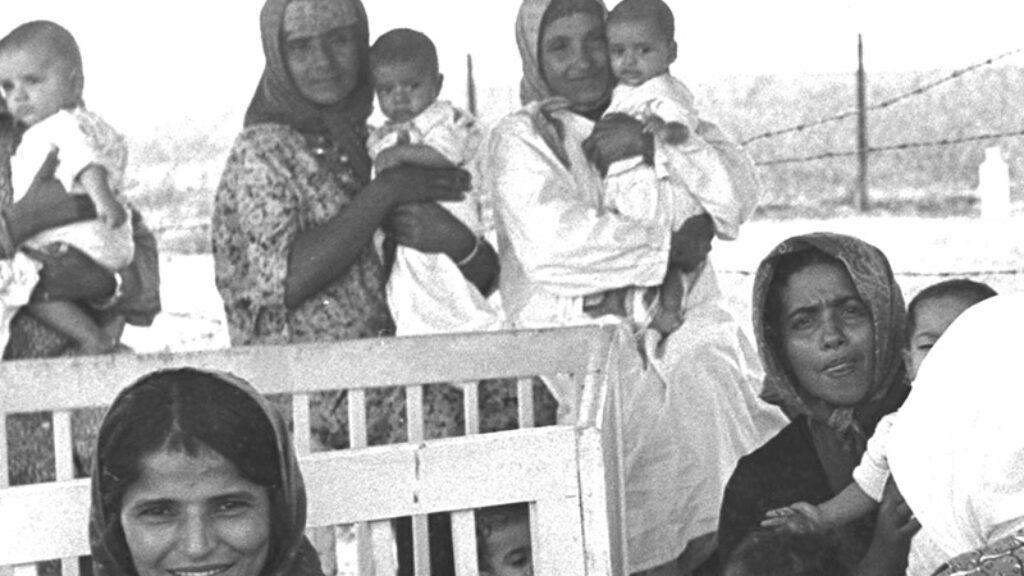

Did the Ashkenazi elite of the early State of Israel conspire to systematically kidnap Yemenite Jewish children?

Of Spies and Centrifuges

Jay Solomon traces decades of spy games between the United States and Iran, a conflict, he writes, “played out covertly, in the shadows, and in ways most Americans never saw or comprehended.”

Eichmann, Arendt, and “The Banality of Evil”

Richard Wolin’s review of a new book about Adolf Eichmann caused a stir, mainly about Arendt. His exchange with Seyla Benhabib on the banality (or not) of evil.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In