Letters, Spring 2023

Cliff-Hangers

When I first read Hillel Halkin’s assertion in “On That Distant Day” (Winter 2023) that “for years now, Israel has seemed to me like a man sleepwalking toward a cliff” and “now we’ve fallen from it,” I thought it was excessive, though I shared his concerns about the Likud’s coalition partners (Zionist theocrats, anti-Zionist free-riders). Writing now, in the midst of the crisis over judicial reform forced by the new government, I am afraid that Halkin is right. More worryingly—for who am I, after all?—so is President Herzog. In his recent address to the nation he warned that Israelis are about to “fall off a cliff.”

Sarah Gold

Jerusalem, Israel

I agree with Hillel Halkin’s concerns about the future of Israel. However, I disagree with his choice of villains. He blames Judaism, not Zionism. This lets secular Jews off the hook. First, there are many different views of Judaism, not all of them ultra- nationalist. Second, the settlements were originally supported by a Labor government, not a religious one. His use of Yehuda Leib Gordon’s poem, which argues for the Israelite monarchy against the prophet to underline his point, is also questionable. The ancient prophets did not fight for a theocracy so much as for a just state. Sure, there are many Orthodox nationalists, but I would argue the problem is nationalism (and greed). Finally, it is not just religious people who say “God is on our side.” In fact, it is precisely a truly religious person who constantly questions whether he is worthy of God.

Eli Leiter

via email

Hillel Halkin’s piece has been with me continually since I read it and has been the subject of several dinner party conversations. After one dinner, I forwarded the link to those who were there, with the following comment:

It is indeed very dark, but it is also deep—the work of someone who has been wrestling with these issues for well over half a century. I spent much of that half century disagreeing with Halkin, but, as he says, “This time it is different.” He concludes the article with his letter to his friend in Portugal:

What more can I say? We’re both old now. Neither of us will live to see the end of this. I will die, anguished, in my country and among my people, and you will die, tranquil, among foreigners in a foreign land, and it is good that you don’t envy me and that I don’t envy you, and that each of us will have the death he chose.

Halkin and I are contemporaries, so I too will not live to see the end of the worrying developments in Israel. But if the friend to whom he is writing is anything like me, someone who has lived in Israel, who has been intimately entangled with it, whose life was transformed by that relationship in ways beyond measure, I can venture that his former neighbor will not die “tranquil, among foreigners in a foreign land.” Rather, he will die anguished that Israel itself has become “a foreign land.” This is certainly not the death that I would choose for myself, but we do not get to choose our death any more than we chose the birth that started the journey.

Louis D. Levine

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

For further discussion of Hillel Halkin’s “On That Distant Day,” read his exchange on the topic with writers Emily Amrousi, Elli Fischer, Mosheh Lichtenstein, Ze’ev Maghen, Mikhael Manekin, Neil Rogachevsky, and Gil Troy, as well as his reply.

Jewish Princes

I enjoyed the three-way discussion John J. Collins establishes in “Like a Son of Man” (Winter 2023) between himself, Israel Knohl, and Daniel Boyarin about the possible Jewish roots for the Christian concept of a divine messiah. But I think that, in the intensity of the discussion, some simpler conclusions have been overlooked. The royal son of God motif in some biblical poetry is part of the larger literary heritage of the ancient Near East, in which the earthly king is the adopted son of the ruling god. There is no hint in this of a supernatural messiah, even though much later these texts became part of the “messianic verses.” The sudden appearance of a messiah in the Psalms of Solomon and then later texts is most likely not the reappearance of a long- held Jewish belief but rather a contemporary response to unhappiness with Hasmonean rule.

I would contend that the “Son of Man” in the book of Daniel is the angel-prince of Israel in heaven, as the animal creatures who precede him are the angel-princes of the various empires. The later use of the phrase in the Pseudepigrapha is hard to interpret but ultimately had little influence on either Jews or Christians. It seems to me most likely that some of the earliest proto-Christians, still struggling to get a handle on the meaning of Jesus’s life and execution, settled on the term “Son of Man” as the proper title for Jesus, and some of that language was retained in the Gospels. The title was abandoned once Paul and his cohorts defined Jesus as the Christ. I would suggest that the Christ idea is not based on Jewish precedents except in the most generalized way. The Christ is the original idea that made Christianity a new and distinct religion.

Stephen M. Wylen

Wayne, NJ

Nietzschean or Not?

I’ve been a Berdichevsky fanboy since I was six years old, when my father, Rabbi Samuel Z. Fishman, submitted his PhD dissertation on Berdichevsky at UCLA in 1969. Reading Shai Secunda’s review of Zilbergerts’s The Yeshiva and the Rise of Modern Hebrew Literature (“The Fierce Lust for Contemplation,” Winter 2023) stirred the pleasures of familiar skepticism. Secunda refers to “Nietzschean Hebraist and Volozhin graduate Micha Yosef Berdichevsky.” Hebraist and Volozhin graduate? Those are settled facts. But does reading Nietzche make one a Nietzschean? Maybe not. As my father wrote, citing Aliza Klausner-Eshkol:

The evidence offered by the men who were contemporaries of Berdichevsky is divided: Ahad Ha’am, Yaakov Rabinovitz, Yosef Klausner, and A. D. Gordon believed that Berdichevsky was indeed a Nietzschean; Yosef Hayim Brenner, Hayim Tchernovitz (Rav Tsa’ir), and F. Lachover minimize Berdichevsky’s dependence on Nietzsche.

I leave it to professional scholars to say more about whether Berdichevsky may be more properly described as an iconoclastic rival to Ahad Ha’am. Certainly his advocacy of Hebrew revival and Jewish liberation set sail from a home port in the Jewish world, as Zilbergerts’s book suggests.

David M. Fishman

via email

Kaplan, Conversos, Collapse

As a Torah Jew, I don’t share Mordecai M. Kaplan’s enthusiasm for the notion of Judaism as an “evolving religious civilization.” (Jenna Weissman Joselit’s “To Whom It May Concern: Mordecai Kaplan the Diarist,” Winter 2023.) I’ve witnessed all too well the spiritual and, yes, cultural devastation this “post-halakhic” model has visited upon American Jewry as a whole, as well as upon close family members. Judaism is simply and inevitably relegated to whatever is convenient, with no sense of obligation. If anything, Kaplan’s Reconstructionism harkens back to another “evolved religious civilization”: that of the conversos in medieval Spain, and in particular some of their more nefarious leaders such as Avner of Burgos, and Shlomo of Burgos, later known as Pablo de Santa Maria. That, in my estimation, is a legacy to put behind us as swiftly as the winds accompanying a fierce tornado on the Midwestern prairie!

David L. Blatt

via email

Open Letters

Nearly three decades ago, Gary Smith and I proposed to publish the correspondence of George Lichtheim and Gershom Scholem. Gary wrote to Miriam Lichtheim, George’s sister and a distinguished Israeli Egyptologist, suggesting the project and requesting permission. She refused on the grounds that her brother would never have allowed private matters, including his health and mental anguish, to be made public in this way. I see from Benjamin Balint’s very welcome article, “George Lichtheim’s Marxmanship” (Winter 2023), that this correspondence has now been publicly quoted. A complete edition of Lichtheim’s correspondence would still be valuable.

Mark Simon

via jewishreviewofbooks.com

Suggested Reading

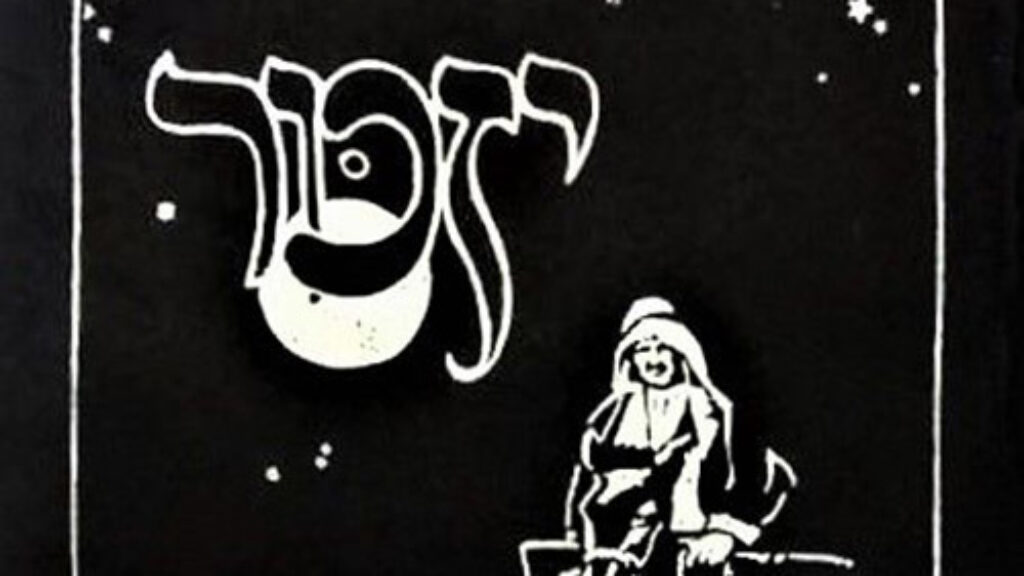

Let the People of Israel Remember

The earliest literary commemoration of Zionism’s fallen heroes was a book entitled Yizkor, published in Palestine in 1911 by members of Poalei Zion (Workers of Zion).

Michael Chabon’s Sacred and Profane Cliché Machine

What's wrong with "knocking down walls"? Well, several things...

Freedom Riders

There is nothing subtle about the theme that runs throughout Philadelphia's National Museum of American Jewish History.

Persian Daughters of Israel

Leah Sarna imagines Jewish and Gentile women doing their laundry on the banks of the Tigris, sharing tricks for keeping their headscarves tied and their bedrooms pure. She reviews Shai Secunda’s new book on just how Babylonian the Babylonian Talmud was.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In