With Interest

In November 2002, a prominent Al-Qaeda website posted a 4,000-word diatribe described as a letter from Osama bin Laden to the American people. In the course of the screed, which purports to explain the grievances of the Muslim world, bin Laden takes special care to lay out the reasons for America’s moral inferiority. High among them, he writes, is the fact that:

You are a nation that permits usury, which has been forbidden by all the religions. Yet you build your economy and investments on usury. As a result of this, in all its different forms and guises, the Jews have taken control of your economy, through which they have then taken control of your media, and now control all aspects of your life making you their servants and achieving their aims at your expense.

Here was a compact summation of a centuries-old case for anti-Semitism, complete with the identification of capitalism with usury, the identification of usury with the Jews, and the assertion of a resulting Jewish conspiracy to dominate non-Jewish majorities through the exercise of economic, social, and political power. It showed that Islamism is not so disconnected from prior political and cultural extremisms. But it also evidenced the still thorny and complex relationship between capitalism and the Jews.

Much has been written on that subject through the years, by anti-Semites, by friends of the Jews, and, not least, by many Jewish writers—from Moses Mendelssohn to Milton Friedman. It is a subject riddled with mysteries and contradictions: Why did the decline of Christian prohibitions on usury make the Jews more rather than less resented for their economic prowess? Just why have Jews around the world in fact been such successful capitalists? Has that success helped or harmed the Jews’ attachment to their religion? How could Jews be at once so closely identified with both capitalism and the assault on capitalism by socialism and communism? And what explains the exceptional persistence of the familiar tropes of anti-capitalist anti-Semitism—demonstrated by Bin Laden’s charges?

These questions point to even deeper dilemmas regarding the social and cultural character of capitalism, and the inevitable scars and distortions wrought upon the Jewish soul by the struggle for survival in the Diaspora. It takes a scholar of uncommon broad-mindedness to take up such large problems, which combine economics, history, theology, and philosophy.

In his new book, Capitalism and the Jews, Jerry Z. Muller fully acknowledges that he has taken on a daunting task. And rather than undertake a futile effort to be comprehensive, he approaches the subject from a few distinct angles, and attempts especially to counter some easy and commonly held assumptions. The result is an accessible, intriguing, and singularly perceptive little book.

Muller is a professor of history at The Catholic University of America and the author of several books on capitalism and the history of economics (most notably The Mind and the Market, published in 2002). He is certainly far more a scholar of capitalism than of the Jews, and his book generally uses the Jewish question as a lens through which to better understand the market economy and its social implications, rather than the other way around. But in the process, he clarifies the tension between the Jewish world and the modern world in a way that students of Jewish ideas will find very helpful.

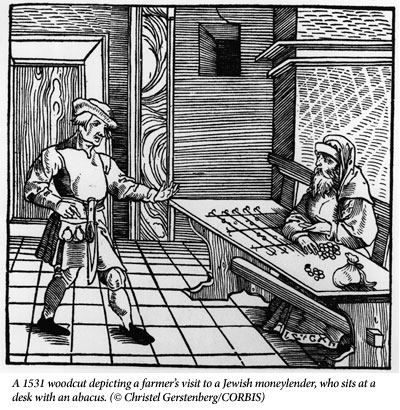

He begins, like bin Laden, by looking at the identification of the Jews with usury. Moneylending was forbidden to Christians by the Church and therefore left open only to Jews in medieval Europe. This defined their identity in European thinking well into the capitalist age. As capitalism advanced across the continent, Muller argues, anti-Semitism was often a surrogate for anti-capitalism, and vice versa. The new economic thinking was understood by some (especially among those most injured by its consequences) as essentially an extension of usury—of the making of money from money, and of the elevation of trade over work—all of which had long been associated with the Jews. Capitalism was therefore seen as a Jewish idea, a kind of conversion of Europe to Jewish ways of thinking. “The Jews have emancipated themselves insofar as the Christians have become Jews,” Karl Marx infamously wrote in 1844.

This view was further strengthened, as Marx’s comment implies, by evidence that the Jews were thriving under capitalism. And indeed they were. Muller, with a keen historian’s eye, brings to bear a mountain of evidence to illustrate Jewish advancement in those nations where capitalism took hold.

This, he contends, in an argument indebted to Max Weber’s famous account of the “Protestant Ethic,” had more to do with Jewish culture than with medieval Jewish moneylending. “The life of mitzvoth,” he writes, “meant a style of life based on discipline, on the conscious planning of action . . . Jews came from a culture that favored nonviolent resolution of conflict, and that valued intellectual over physical prowess. All of this was a recipe for what economists now call cultural capital.” And capitalist success is at least as much a function of cultural as of economic capital.

That success, of course, brought a further identification of capitalism with the Jews, and further resentment, especially when capitalism brought dislocation. As Muller shows, the response of the Jews to that resentment, and so to mounting anti-Semitism, played a crucial role in giving shape to Jewish life in the 19th and early 20th-centuries.

Some Jews internalized the criticism and were driven into the arms of anti-capitalist movements, where they soon became prominent voices. But most, Muller argues, defended capitalist economics and the liberal politics that often came with them. This is not the image we generally have of the economic and political views of European Jews before the Holocaust, and perhaps the book’s most significant contribution is Muller’s careful parsing of the evidence to show that the vast majority of Jews in pre-war Europe supported pro-market liberal parties, and that openness to socialism (not to mention communism) was a decidedly minority view.

“The identification of Jews with capitalism was based on an exaggeration of the reality that Jews really tended to be more successful capitalists,” Muller writes. “The identification of Jews with Communism was grounded in the fact that while few Jews were in fact Communists, men and women of Jewish origin were particularly salient in Communist movements.” It was their effectiveness, not their numbers, that made the Jews stand out in anti-capitalist parties.

But whatever the reason, they did stand out, and both before and after the Second World War, this meant that Jews were identified with communist movements—so that having been resented as the embodiment of capitalism, they now came to be hated as the enemies of it. As first Russia and then much of Eastern Europe came under communist domination, men and women of Jewish origin were prominent among the leaders of almost every communist regime, and local populations increasingly came to resent the Jews as their oppressors. As the Chief Rabbi of Moscow is said to have told Leon Trotsky (born Lev Bronstein): “The Trotskys make the revolution, and the Bronsteins pay the price.”

The response of some of the “Bronsteins” was of course to turn to Zionism. Oddly, Muller has almost nothing to say about the deep links between socialist idealism and the Zionist movement, though he devotes his final chapter to an analysis of the links between nationalism and capitalism. Far from a reversion to ancient blood ties in response to the displacement brought about by capitalism, he writes, nationalism was essential to bringing about the efficiency and order demanded by the capitalist economy. Strong central governments ruling cohesive nation-states are far more hospitable to orderly markets than are loose multi-ethnic empires, and the division of much of Europe into ethnic states was therefore an element of the larger process of industrialization and the evolution toward markets.

Just like the emergence of capitalism, and of anti-capitalism, this turn in European thinking also brought with it a wave of anti-Semitism. Nationalism left the Jews without a home, and in some places (above all Germany of course, and with it much of Europe when the Second World War came) in outright mortal danger, and worse.

In the end, the picture Muller paints is one of Jewish success against all odds—with every turn in the story providing fresh fodder for virulent anti-Semitism but also fresh paths to Jewish prosperity and prominence. Reactions against capitalism have often taken the form of reactions against the Jews, and it is in those places where capitalism has been ascendant and harsh reactions rare (especially the United States and Britain) that the Jews have thrived most. Their fate, Muller suggests, has been closely tied to the fortunes of capitalism.

While he tells a gripping story, and illustrates his case with copious evidence and arresting insights, Muller does leave some holes, especially with regard to Jewish religious and cultural life. He seems to describe both Jewish capitalism and Jewish anti-capitalism as paths away from tradition. But in fact, the story of Jews in the age of capitalism has not simply been a story of increasing alienation from orthodoxy. Among the most interesting facets of that story are the means that Jewish communities have developed to take part in the economic life of the larger society while maintaining the coherence and integrity of their religious life. Almost entirely missing from his story, moreover, is the distinctly Jewish critique of capitalism: the ways in which some Jewish moral teachings, especially the emphasis on justice drawn from the words of the prophets, have been employed in condemnation of the ethic of capitalism.

In his effort to highlight Jewish support for capitalism, Muller shows how the cultural capital of the Jewish community, combined with some powerful biblical injunctions to hard work and honest dealing, were important in giving form to what on the surface was a secular commitment to the ethic of the market economy. But he ignores the mirror image of that phenomenon: the ways in which echoes of the biblical injunctions to seek worldly justice were often plainly audible in the passion of Jewish socialists, even when they sought to couch their criticism of the market system in secular terms. Such echoes are, at least implicitly, still very much a part of many Jewish responses to democratic-capitalism in America, in Europe, and in Israel.

Capitalism and the Jews is, in short, more about the former than the latter, but Muller does not pretend otherwise. And by providing many valuable insights about the modern economy gleaned from the varied roles the Jews have played in its development, he also raises questions pertaining to Jewish thought and history that will no doubt be taken up by others.

In the meantime, in a lean and compact volume, Muller has offered a rich and valuable history filled with insights about the character of capitalism and the sources of anti-Semitism—both of which could hardly be more timely subjects.

Suggested Reading

The Mabam Strategy: Israel, Iran, Syria (and Russia)

In 2017, Israeli fighter jets hit an Iranian weapons facility in Syria, and such strikes have continued over the last 18 months. But as Assad solidifies his victory in the Syrian civil war while Iranian and Russian forces remain on the ground, the next Israeli government must rethink its strategy in “the campaign between the wars,” known in Hebrew as mabam.

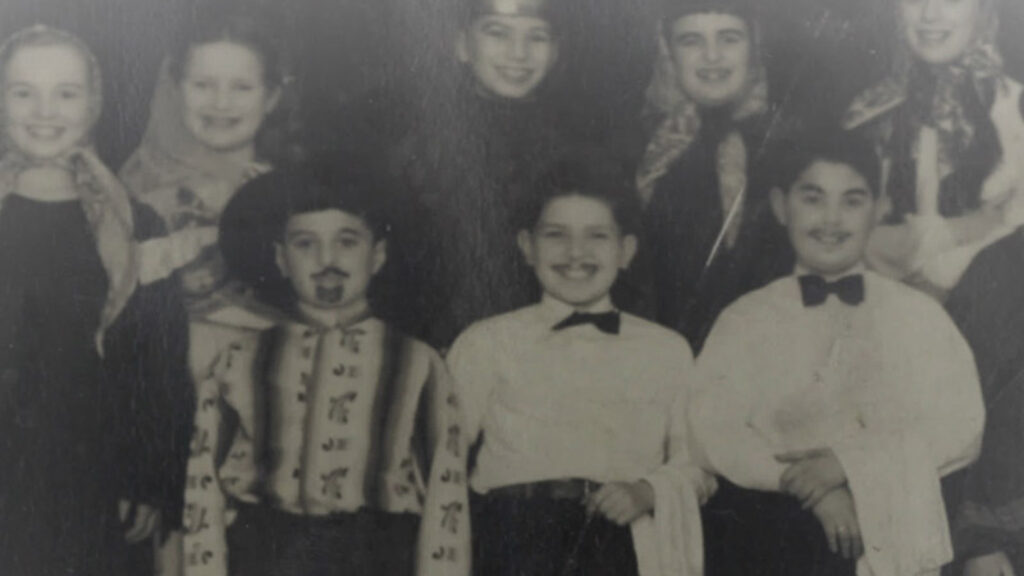

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

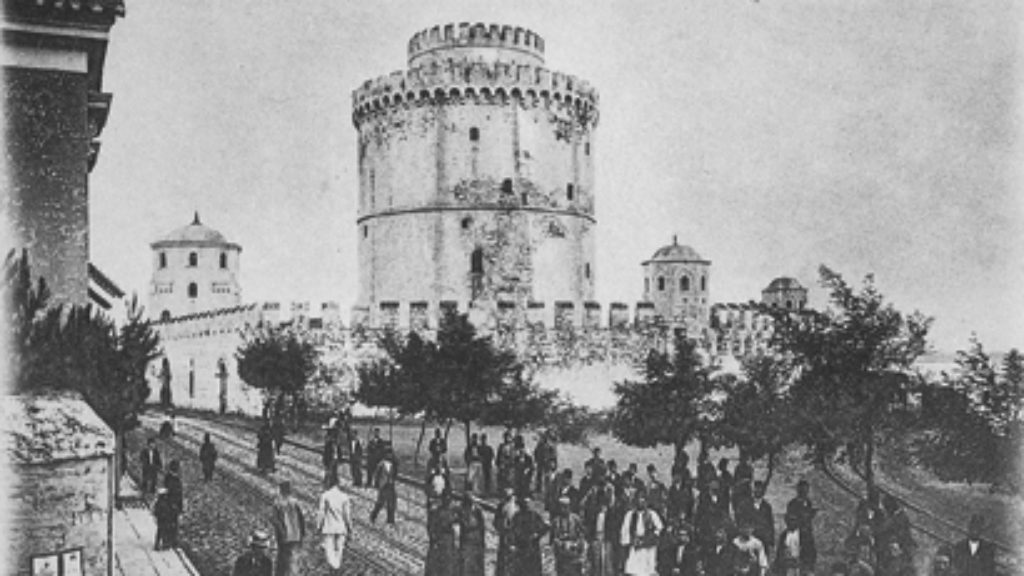

Jerusalem of the Balkans

In 1911, David Ben-Gurion spent several months in Salonica and declared that it was "the only Jewish labor city in the world." Now, because of an open-minded mayor and his nationalist opponents, this formerly Jewish city is experiencing a peculiar mix of Jewish memory and anti-Semitism.

Equine Ambles into a Watering Hole: An Interview with Jessica Cohen

An interview with Jessica Cohen—winner of the 2017 Man-Booker International prize for her translation of David Grossman’s Horse Walks Into a Bar—on translating Hebrew literature and jokes.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In