War & Peace & Judaism

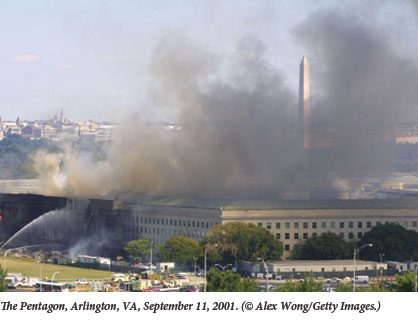

Robert Eisen was walking to his office at George Washington University on September 11, 2001 when he caught sight of an ominous dark cloud in the vicinity of the Pentagon. This moment marked the beginning of a great change in his life. Once he had absorbed the impact of what had occurred, he reports in The Peace and Violence of Judaism, he came to realize that he could “no longer remain aloof from broad global concerns.” He had to “come out of the ivory tower” of medieval Jewish philosophy and “work on global issues involving religious conflict.”

Religious violence, according to Eisen, “has become one of the most—if not the most pressing issue of our time,” and the Jewish religion itself constitutes no small part of the problem—not in the Diaspora, of course, but in and around Israel.

The conflict between Israelis and Palestinians is at the center of the tensions between the Western and Islamic worlds, and it is no exaggeration to say that the well-being of our world in the long term may depend on its outcome.

Eisen believes that he can help to mitigate the threat that this conflict poses by clarifying the extent to which Judaism has helped to heat it up, as well as the ways in which it could help to cool it down. In addition to providing his readers with an inventory of both the violent and the peaceful strains of Judaism, he ventures in his epilogue to offer some tentative suggestions as to how peace-seeking Jews might construe what is admittedly an ambiguous tradition in such a way as to make the Middle East a safer place.

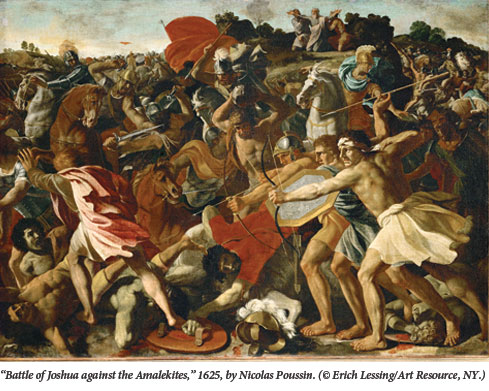

Eisen freely acknowledges the worst things about the Bible. Above all, it authorized God’s chosen people to commit genocide against the inhabitants of the land that He had promised to them. And even if the modern scholars who consider the account of the extermination of the Canaanites to be altogether fictional are correct, this doesn’t eliminate the problem. “The biblical text is still reprehensible for depicting genocide as a good thing; after all, it is commanded by God and carried out at His behest.” In other ways, too, “the Bible encourages its adherents to act violently against outsiders.” There are, for one thing, the passages in the prophetic literature “that predict violence against the Gentile nations during the messianic era.” On the other hand, the “vast majority of non-Israelites” who appear in the Bible “are not the object of scorn, much less genocide.” In many respects, in fact, the Bible “promotes peace between Israelite and non-Israelite.” Most notably, there are the prophetic passages that “describe the messianic period as an idyllic era in which the Gentile nations will acknowledge God’s sovereignty, humanity will be unified, and universal peace will reign.”

Despite his clear preferences, Eisen doesn’t rush to make the kind of pronouncements one might expect. Instead, he asks, among other things, “Why should we choose the peaceful passages in the Prophets over the bellicose ones?” The answer, Eisen makes clear, cannot be found through recourse to the rabbis. “Jewish scholars and ethicists,” he tells us, “commonly see rabbinic Judaism as a school that rejected much of the violence in the Bible and in its stead favored a more peaceful understanding of Judaism.” They’re right. But as Eisen takes pains to demonstrate, “another reading of rabbinic Judaism is possible, according to which the rabbis preserved the violence of the Bible.” And this reading is right too!

Nor can any subsequent school of Jewish thought tell us which of these readings is really the correct one. Among the rationalists and the mystics, and among the Zionists, religious and secular alike, the two divergent viewpoints he has located in the Bible are amply represented. Maimonides, for instance, the greatest of the medieval Jewish philosophers, seems to have interpreted the Bible’s standing order to annihilate the Amalekites as a commandment that “is focused on the eradication of incorrect philosophical conceptions and is therefore not concerned with physical violence.” At the same time, however, he “justifies the war against the Canaanites on the basis of philosophical considerations, leaving the violence of the biblical narrative in place.” Kabbalah is intolerant toward non-Jews and “its doctrines, therefore, indirectly promote violence against them.” But popular Kabbalah in our own day has a universalistic orientation. “Both religious and secular Zionism have exhibited violent strains throughout their history,” but both have also displayed more pacific tendencies.

Unfortunately, history can’t solve the problem created by our tradition’s duality by teaching us how progress makes it possible for “violent Jewish sources” to “be defanged through interpretation.” For “one has to be prepared for the possibility that in our period interpretation might yield views that are more violent than their predecessors.” Indeed, that has already happened in the case of the “readings of Judaism espoused by Meir Kahane and Zvi Yehuda Kook, which have promoted exceptionally militant forms of Zionism.” And who’s to say that their interpretations are illegitimate? Not Eisen, anyhow, much as he

deplores their violence-prone theologies.

Eisen concludes the main part of his book on a modest note of hope that his analysis of his religion’s dual nature will inspire scholars who belong to other Abrahamic communities “to examine their own traditions and engage in the same kind of reflection.” From the language that Eisen employs here, one might suspect that he views Christian religious extremism as just as much a threat to the world as Muslim extremism. It is more likely, however, that his even-handedness stems from his irenic outlook. He doesn’t seem to want to say anything that might smack of Islamophobia. In any case, his main focus is on the Jewish world, to which he finally speaks, in his book’s epilogue, in ways meant not merely to inform it but to shift it in the right direction.

Eisen is not someone who is prepared to “declare in postmodern fashion that both readings of Judaism in our study are legitimate and we should leave the decision about which view is correct to the individual conscience.” But if, indeed, we want help in making our own decisions, he tells us, “our only alternative is to go outside the texts and engage the real world. We must focus on the realm of the empirical. More specifically, we must ask which viewpoint makes more sense on the basis of pragmatic and practical concerns.” The reader who arrives at these statements on page 220 (of 280) can be forgiven for regretting the amount of time he or she invested in sorting through and keeping straight the multitude of sources Eisen assembles. What’s the point of learning about them, one might ask, if they just cancel each other out? True, Eisen hastens to identify strains of pragmatic thinking in the writings of the rabbis themselves. But he doesn’t pretend that they are of decisive importance, for, as he acknowledges, he might with comparable ease have collected rabbinic sources that militated against pragmatism.

What, in any case, does Eisen think would be the truly pragmatic course of action for Israel to pursue in its conflict with the Palestinians, a conflict on which, as he puts it, the “well-being of our world” may ultimately depend? It’s not exactly the same as that recommended by the ancient rabbis in the aftermath of the destruction of the Second Temple. “They encouraged their followers to give up their political independence, eschew violence against their enemies, and accommodate themselves to gentile rule. They valued the preservation of the Jewish community over independence.”

Eisen, for his part, “does not deny that Israel should have a strong army and that it should use force in some circumstances.” Where he does follow the rabbis, however, is in making survival his central concern. And Israel, he asserts,

has the best chance of surviving if it adopts a strategy that involves shrewd diplomacy designed to separate radical Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims from moderates by offering incentives to them to live in peace with Israel while at the same time isolating the radicals. Creating a Palestinian state would be part of that strategy because it would pull the rug out from under the radical elements in the Arab world, who have used the Palestinian issue to drum up support for their cause.

I know Jews who agree with Eisen’s policy recommendations, and I know others who don’t. But I’m not going to tell any of them that the epilogue to The Peace and Violence of Judaism is required reading. The former will learn nothing new from Eisen’s cursory tour of the present situation, and the latter will be unlikely to find his policy recommendations very persuasive. For they generally think that they are being pragmatic, too, in opposing the creation of a Palestinian state precisely because they feel that it would constitute an unacceptable threat to Israel’s survival. This is good evidence of what Eisen himself recognizes, i.e., “[w]hat is considered pragmatic will vary considerably from person to person,” and it demonstrates the insufficiency of the guidelines he offers us.

Eisen has every right, of course, to emerge from his ivory tower to help resolve the world’s problems, but he doesn’t seem to have brought with him anything that will be particularly useful in accomplishing his goals within the Jewish world, nor does he have anything new to say. If he succeeds, however, in his announced goal of inspiring Abrahamic imitators, his labors will not have been in vain—especially if there turn out to be some Ishmaelites among them. For it is the Muslims of the world, far more than the likely Jewish readers of a book like his, who need to get in touch with the peaceful side of their own religion.

In the context of the interfaith peace work in which he has been extensively engaged, Eisen has encountered over the years many Palestinians, Arabs, and Muslims who have little knowledge of Judaism and many prejudices against it. He once sat, he tells us, “with an Iranian ayatollah at an interfaith conference in Italy who asked me whether it was true that all Jews believed that their messianic kingdom would stretch from the Nile to the Euphrates.” People who share this cleric’s misconceptions could learn otherwise and much else from The Peace and Violence of Judaism. I hope that Eisen can get them to read it.

Like Robert Eisen, Alick Isaacs traces his own book back to a moment of violence. In the early 1980s, when he was walking home from a Talmud class in Birmingham, England at the age of 14, a gang of teenage skinheads spotted his kippa and beat him up badly. While they were still hitting him, he made three vows: “to settle in the land of Israel and to enlist and to serve in an Israeli military combat unit.”

By the time the first intifada erupted, in 1987, Isaacs, who had fulfilled his vows, occupied a post in the real world that forced him to use a truncheon against Palestinian demonstrators. He did so with misgivings that he had failed to face the challenge “of behaving humanely in the face of adversity.” But it was only his service as a reservist in the Second Lebanon War in 2006 that spurred him, two decades later, to write A Prophetic Peace.

While Eisen tells us only that there was a time in his life when he was drawn to the viewpoint from which Judaism is “supportive of violence,” Isaacs reports—with some shame—how whole-heartedly he once adhered to it. “I prayed hard at war” in Lebanon, Isaacs tells us.

I wielded “the God of Israel, who gives strength and power unto His people. Blessed be God” like a sword. I prayed to God “with a two-edged sword in my hand; to execute vengeance upon the nations, and punishments upon the peoples; to bind their kings in chains and their nobles with fetters of iron.”

After having prayed so avidly in the course of the fighting, however, Isaacs faces a predicament.

I cannot strive in my daily practice to emulate my greatest prayers. My most urgent supplications to God and most complete experiences of communion with the words of the siddur are of no use to me. They are no use because I am ashamed of them.

But rather than renounce them in horror, Isaacs has written a book devoted to defanging these parts of the prayer book as well as the rest of the bellicose language found in other layers of the Jewish tradition and forging “a theologically disarmed religion.”

Isaacs agrees with Eisen that one cannot simply bypass the unappealing texts by identifying a contrary tendency within the tradition. He understood from the start of his new enterprise that “dismantling the connection between violence and religion would take more than a dovishly selective reading of the Bible or the Talmud or a prayer book.” Unlike Eisen, however, Isaacs doesn’t see the peace-promoting dimension of Jewish literature, taken by itself, as the best point of departure for further ruminations. What he seeks to supply instead are “theological readings of biblical, rabbinic, and prayer texts in an attempt to make good on both biblical and rabbinic statements that present the entire Torah as a path to peace.”

To do this, one has to go beneath the surface and uncover “the implicit imaginative understanding of faith that courses through the veins of religious experience, animating it from within.” Isaacs therefore proceeds to walk his readers along his “post-Wittgensteinian, post-Derridean path to the implicit side of Judaism.” Yet as he himself acknowledges at the end of A Prophetic Peace, his arguments and interpretations don’t “make for light reading.” In truth, this is an understatement. I will confine myself to stringing together some of his more accessible statements in an effort to clarify, to some degree, the goal at which he finally arrives.

“Despite explicit appearances,” Isaacs tells us, “God—and, by way of extension, everything in the Bible (and, as we learned from the story of Babel, everything in language)—defies absolute or specific translation into human politics.” “Isaiah’s vision of peace,” for instance, “is an impossible one for human hands to mold,” since its accomplishment would require the unimaginable elimination of human baseness. “Peace,” therefore, “is part of an implicit prophetic vision that cannot become political with anything less than the greatest caution. By framing prophecies of peace in messianic time, the prophets leave Jewish history with the legacy of anticipating the impossible.” Consequently, the “messianic vision, rather than fueling our flight toward the end of history, quenches or weakens our impulse to drive history toward any kind of ultimate end.”

These remarks reflect what might be considered to be the main thrust of Isaacs’ book: his rejection of the path of the “disciples of Rabbi Kook,” whom he describes as having “demystified the messianic age, concretizing it in their brand of Religious Zionism, dragging Judaism with them into fierce ideological conflict.” Isaacs’ treatment of rabbinic literature has a rather different polemical edge to it. The understanding of the rabbis that he is combating is not that of Religious Zionists as such but one that generally characterizes Orthodoxy as a whole. It is one that is shared, he notes, even by the liberal pluralists with whom he respectfully disagrees, such as Avi Sagi and Menachem Fisch, who maintain that “the halakha seeks—through interpretation or the assumption of rabbinic authority—to determine either the ‘original’ or the ‘current’ intentions of revelation in definitive terms.”

Isaacs declines to participate in this search for certainty because he believes that everyone who engages in such an enterprise runs the risk of engaging in “religious tyranny” through the imposition of his or her own view on others. A better way to understand the halakha is to conceive of it as something vastly more open-ended.

When viewed in terms of the implicit religious purpose of halakhic argumentation, the manipulation of logic and language produces a body of literature that is perpetually deconstructive and puzzling. Ultimately, it offers an apophatic—backward—path away from singular claims about law, ethics, and justice. The implicit rabbinic voice confounds arrogant delusions about the scholarly acquisition of immutable or divine truth, undermines the scholar’s sense of his power as a legislator of divine law, and leads him to display his fallibility before God. It disarms the potential zealotry that emerges when legislators of religious law believe that they are the executors of his will.

Deprived of any sense that they are in sole possession of the truth, rabbinic scholars can be exemplars of genuine religious humility, which then “becomes a crucial aspect of the irenic quality of rabbinic law and its capacity to serve as a model for negotiating peace.” If this model were to be generally followed, Isaacs appears to believe, people would cease to fight over the divine will in public and “search for God in private.”

In his treatment of both biblical and rabbinic literature, Isaacs follows in the footsteps of other Israeli thinkers who have tried, like him, to drive “a wedge between religious aspirations and politics.” While he thinks that he has improved on them, he does not pretend that his book constitutes the last word on the subject. “Indeed,” he says, “I have developed only one of several possible Jewish paths to peace.”

I’m not sure how good a path it is. If it leads away from a politics infused with messianism and toward greater moderation, it is one that I would be content to see other Israelis pursue. But where does it end? It is Isaacs’ goal, he says, to soften “Israel’s ambitions and convictions” and utilize “the religious tradition to undermine the state’s moral certitude.” He does not neglect to ask whether this can be done “within a context that continues to affirm both the validity of state power and the Jewishness of the state.” In fact, he believes that it can, but says little more.

It would have been reassuring to read in this book, so deeply soaked in the kind of postmodernism that looks askance at the modern state as an instrument of oppression, something like Robert Eisen’s unequivocal affirmation “that Israel should have a strong army and that it should use force in some circumstances.”

Eisen and Isaacs’ books both owe their origins to the violent turmoil of the first decade of the 21st century. Eisen traces his back to a horrifying terrorist attack on America; Isaacs wrote in the aftermath of his participation in Israel’s retaliation against a terrorist attack on its armed forces. But both of these authors are preoccupied much less with the threat posed by enemy terrorism than with counteracting the late 20th-century political theology upheld by some of their own co-religionists, the “disciples of Rabbi Kook.” Both seem to have adhered to it in the past, and both want to replace it now with a tradition—based approach to politics that could claim at least as much legitimacy. Finally, both men have sought to advance this purpose by spelling out their ideas in books published by university presses. But isn’t this, on some level, rather strange?

For virtually all of the readers of such monographs, the high value of peace is a given, as is the compatibility of Judaism with such a priority. Most of the people who hold the beliefs that Eisen and Isaacs are challenging live in Israel and don’t read academic studies of Jewish thought published by American and British university presses—as both of our authors no doubt know. It seems, in the end, that their books constitute not so much attempts to exert influence in places where it might be effective as they do public battles with their own private demons.

But if this is true, it is only insofar as the Jewish world is concerned. Eisen, we know, is already very much involved in interfaith peace work, in which The Peace and Violence of Judaism might be of some assistance. Isaacs, for his part, describes A Prophetic Peace as his own Jewish contribution to a future dialogue in which he would like to see “Jews and Muslims—separately and together—offer each other their version of peace’s meaning for careful and thoughtful consideration.” It is hard for me to imagine an argument as dense as Isaacs’ receiving much attention in such a setting, but if his presentation of his thoughts could help to diminish anyone’s antagonism toward Israel that could only be a welcome development.

In the end, however, the books under review here provide at least as much grounds for concern as for satisfaction. Is it really time for what Isaacs calls “theological disarmament”? Would one want to see his arguments, or perhaps even Eisen’s, couched in more accessible language, put into Hebrew, and widely consulted in the circles that are, in their opinion, in greatest need of them?

Even those of us who share some of these authors’ qualms about the ideology currently animating the national religious camp in Israel have to acknowledge that it has been singularly effective in inspiring young people to do what is necessary to keep their country secure. As has been widely publicized, in recent years representatives of this camp have come to constitute a very largely disproportionate and steadily growing percentage of the IDF officer corps and combat units. If they are theologically disarmed, will they still show up for this kind of duty? If one is to be truly pragmatic, such questions cannot be brushed aside.

Suggested Reading

All-of-a-Kind Americans

In the 1950s, Sydney Taylor’s All-of-a-Kind Family books for children told the story of American Jewish acculturation–and pushed the process forward.

Berdyczewski, Blasphemy, and Belief

Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg, one of the towering figures of the rabbinical establishment, found deep lessons about faith in the writings of the Nietzschean heretic Micha Josef Berdyczewski.

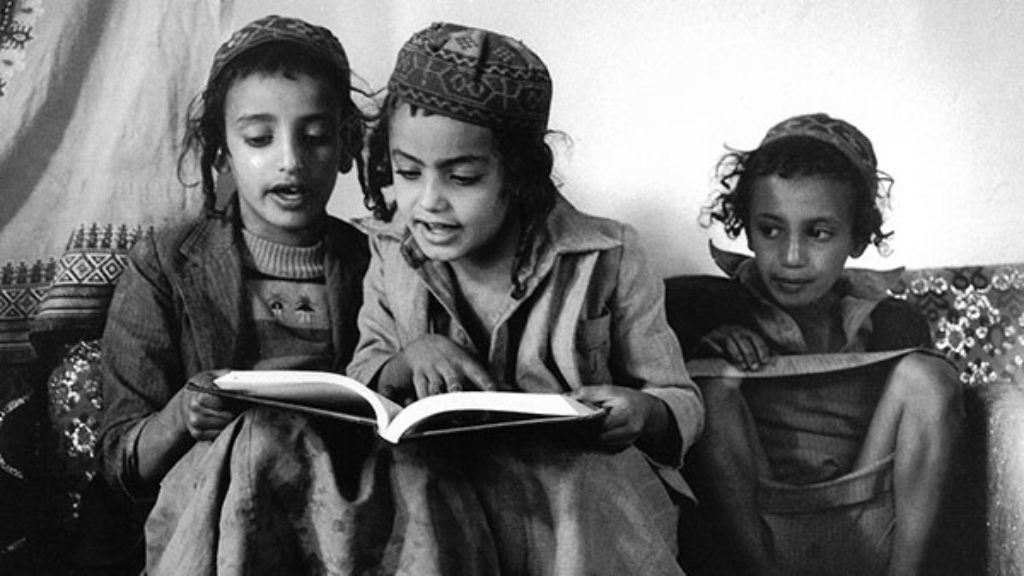

Visiting Yemen in the 1980s: A Photo Essay

"Sometimes one really does find that moment and the image seems to capture a person—this particular Jew, this particular way of life—but often one does not and feels the need to return, to try again." But in this case, there are no Jewish communities in Yemen to return to.

It’s the End of the World as We Know It

Can liberal Judaism survive and thrive in the digital age?

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In