It’s the End of the World as We Know It

In my final year at the Jewish Theological Seminary, we were assigned to take “Senior Homiletics.” Our teacher, Simon Greenberg, was the acknowledged dean of Conservative rabbis in his time. Greenberg, who was in his nineties, was at the end of a distinguished career. He had been the founding rabbi of the synagogue my father later presided over (Har Zion Temple in Philadelphia) and had been a mentor of my father’s, so to me he was a part of living Jewish history.

In our first class, he stood before the class and made an apodictic pronouncement: “Your job as rabbis in America . . . ”—feel free to complete this sentence on your own before I tell you how Greenberg concluded; I assure you, the two endings will not be the same. “Your job as rabbis in America,” he said, “is to explain America to your congregants.”

I was thunderstruck. That was what he thought our job was? No doubt it had been his job. For decades, JTS would not allow any classes in Yiddish because it had been vital to Americanize the rabbinate, but that wasn’t an issue by the 1980s. Solomon Schechter famously told students they could not be rabbis in America without understanding baseball, but my congregants would know as much about America (and baseball) as I did! They would be born here as well. (As it turned out, I ended up taking a synagogue with a large immigrant population from Iran, so somewhere in gan eden, Rabbi Greenberg is laughing at me. Still, I wasn’t wrong to be flabbergasted.)

I remembered Greenberg’s pronouncement as I was reading Danny Schiff’s perceptive, thoughtful, and important book, Judaism in a Digital Age. He begins by asking why Reform and Conservative Judaism are in decline. That the liberal movements are in decline is indisputable, and the numbers are pretty startling. According to a recent report from the Pew Research Center:

In the new survey, a quarter of adults who are currently Jewish or were raised that way say they were brought up in Conservative Judaism, while 15% identify as Conservative Jews today. For every person who has joined Conservative Judaism, nearly three people who were raised in the Conservative movement have left it.

Schiff, who was himself ordained in the Reform movement, wisely avoids the usual inaccurate and censorious explanations for these developments.

No, it is not because the liberal movements did not change quickly enough to keep up with the times. Nor is it because they were too lax; as Schiff writes, “In 1990, with 73 percent of American Jews identifying as Reform or Conservative, only 10 percent of American Jews attended synagogue weekly, [and] only 12 percent reported that they kept kosher.” The rabbis were chasing the congregants, not the other way around. Take the Conservative movement’s famous 1950 “driving teshuvah,” which some critics regard as the beginning of the end of the movement. One problem with this version of history is that, for better or worse, the rabbis who wrote the responsum allowing congregants to drive to shul on Shabbat under certain circumstances did so because people were already driving, not because they weren’t. The same can be said of the Reform movement’s acceptance of interfaith households (whether intermarried couples are accepted or not, intermarriage climbs, as do the number of households with little or no observance).

So why are the Reform and Conservative movements in such steep decline? Schiff’s answer is that it is because they were created in the nineteenth century to answer a question Jews no longer need to ask: How do we become modern? Or to take Simon Greenberg’s twentieth-century version of the question: How do we become American? Greenberg spoke almost as much about Abraham Lincoln as he did about Rabbi Akiva, but by the late twentieth century, liberal Jews took America for granted (my immigrant congregants notwithstanding). The primary default identity was no longer Jewish; it was American—and thoroughly modern.

Now, Schiff argues, the challenge to the relevance of the liberal Jewish movements is even more extreme: Reform and Conservative Judaism were designed to usher Jews into modernity, but “modernity is over.” We live in a new digital age. (Orthodoxy, which was originally born in opposition to modernity, faces a somewhat different set of challenges.)

Schiff’s book begins with the bold declaration that “somewhere around 1990, everything changed,” continuing:

Back then, of course, nobody realized that any sort of transformation was underway, but, with hindsight, the revolutionary shift now seems clear. The revolution started with technology, but it didn’t end there. Ultimately, a new era emerged that led to a reevaluation of many fundamental ideas, altering the way we think about much of what is important.

Schiff is right that the internet did more than just streamline commerce and communication. It has radically reshaped the norms and forms of our lives, especially since the rise of smartphones and social media. Schiff quotes Daniel Goleman as calling the changes we have recently lived through as “an unprecedented experiment with an entire generation”:

The way in which humans have transferred skills in emotional intelligence, in managing ourselves and in our relationships is through face-to-face interaction, which means that this skill set is not being learned the way it has been in past generations.

The way we present ourselves and act with others has certainly changed—and not for the better. What you post may not be what you think, but it is certainly what you wish others to think that you think. Your photos may not be who you are, but they certainly depict how you wish to be seen. Norms of privacy and expectations of authenticity have changed. We now interact with each other and inhabit the world differently. As Schiff puts it:

Over the course of three decades, our technology, culture, society, financial system, media, marriages, families, sexuality, privacy standards, and even our mental functioning have changed. . . . The way we live, the way we work, the way we interact, the way we communicate, the way we think, and the way we curate and perceive our reality have all been refashioned. . . . This digital age is thoroughly discontinuous with what preceded it.

But if this new digital age has changed everything and modernity is over, then precisely those Jewish movements whose purpose was always to mediate between tradition and modernity will not survive. “Sooner or later,” Schiff writes, “Reform and Conservative Judaism will become entries in the history books, alongside modernity itself. Pockets of strength will likely continue for decades, but the waning years have arrived.”

So what comes next? And how will liberal Judaism, or any Judaism, speak to this new age? Schiff has read futurologists like Ray Kurzweil and Yuval Noah Harari closely, and he believes that “the technological and civilizational changes that will unfold over the next several decades will be far more momentous than those which have transpired since 1990.” To take the issue that has seized the headlines in the few months since this book was published, Schiff accepts that in the very near future—decades, not centuries—artificial intelligence (AI) will outstrip human intelligence. This will fundamentally alter, if not supplant, human life as we know it. “We are very close to the day when fully biological humans . . . cease to be the dominant intelligence on the planet,” Kurzweil writes. Harari has famously argued that our near-term descendants, if not we ourselves, will no longer be “fully biological humans,” because we will soon engineer ourselves into another species entirely. If such transhumanist predictions sound too fantastic—and they may be—recall that none of us had heard of ChatGPT a few months ago; now it has already disrupted higher education, and that would seem to be just the beginning.

What, then, can Judaism contribute to such a future? Schiff’s answer is surely right in its broad outlines. He knows that the core elements of Jewish life—“engaging with God, Torah, Israel, Jewish law, and Jewish time, as translated into patterns of living structured by mitzvah, halakhah, and mores”—must endure for there to be authentic Judaism. But the future can be energized, he suggests, not simply by reiterating the centrality of old forms of Jewish practice but by applying Jewish ideas to emerging ethical concerns.

Judaism, he argues, must find ways to rearticulate and apply the values that emerge from its profound theological humanism in a future in which those values will be endangered. Schiff runs through several questions that future Jewish thinkers must address, including those that arise from biotechnology, genetic engineering, the possibility of radical life extension, and, more fundamentally, the idea that human life, or whatever comes next, need not be biologically embodied. However, while he quickly sketches some of the theological and ethical questions these developments will raise, Schiff doesn’t give a very robust sense of how they should be addressed. His book is more programmatic than philosophical. He doesn’t tell us much about what Jewish texts and ideas should be drawn upon in answering these questions or why the postmodern world will require specifically Jewish answers.

The concluding pages of Judaism in a Digital Age are, nonetheless, an eloquent paean to the enduring vitality of a uniquely human perspective on the world—vulnerable, creative, and ultimately unpredictable. Schiff is convinced both of the fertility and the enduring relevance of the Jewish contribution to that human perspective.

The tension at the heart of Schiff’s enterprise is the same as the one at the heart of the modern religious project: how does one sustain an open attitude toward the world while remaining faithful to ancient traditions? The changing role of women, to take a nontechnological example, cannot be met with generalizations or good intentions: either they can be rabbis or they cannot; either they count in a minyan or they do not. To take a position either way is to slice off a considerable part of the Jewish world and to make one’s Judaism irrelevant to them.

Such binary choices cannot be remediated by the truth that Judaism has a great deal to say about the advance of bioengineering. In some ways, despite the range of Schiff’s reading and concerns, there is something essential missing from the book. How do we get people to care about the core elements of Judaism when there are so many distractions and alternative systems, not to speak of the option of choosing no system at all?

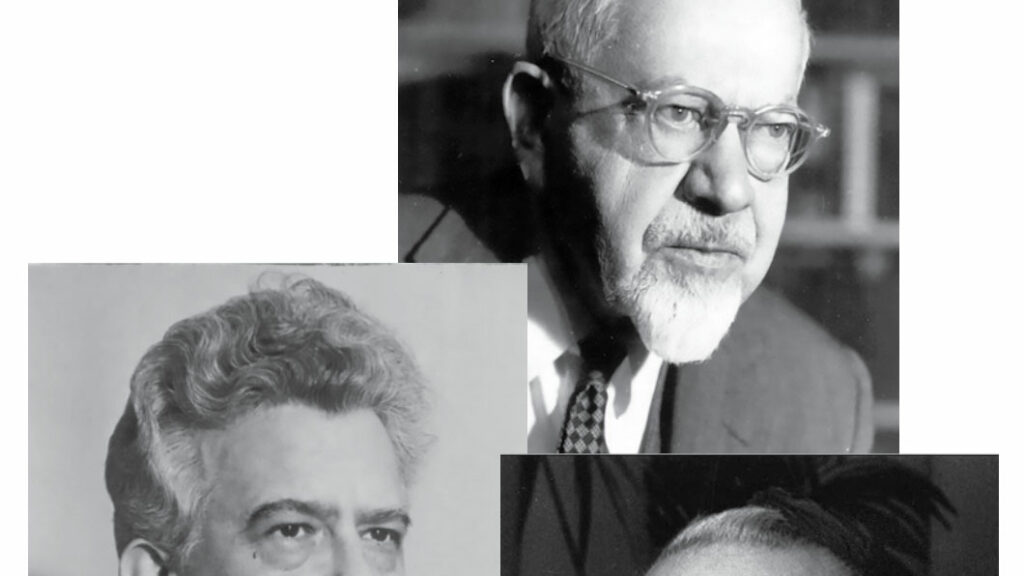

Schiff writes that the synagogue “continues to be essential” and that Jewish practice is indispensable to a living tradition. But he also knows that synagogues are decaying, at least within the liberal movements, which are his central concern. COVID-19 dealt in-person synagogue attendance a blow from which many Conservative and Reform shuls have not recovered. In a final chapter titled “Vehicles for the Road Ahead,” Schiff surveys liberal discussions of halakha, which may point a way forward for the liberal movements. It is an interesting discussion (though strikingly, left-wing Orthodox thinkers such as Eliezer Berkovits, David Hartman, and Nathan Lopes Cardozo dominate the survey), but it is not at all clear how it might be applied to actual liberal Jewish communities. In a poetic summation, Schiff writes:

Halakhah, then, can be described with varying metaphors: It is the practice that emerges from the conversation of an encampment. It is a colorful, musical symphony. It is the encapsulation of the ethical and the holy in a lived community. It is a river that flows with unexpected turns. It is a way of responding that is built upon unalterable principles but which nevertheless evolves and relates with relevance to contemporary conditions.

Jewish thinkers, in particular Conservative rabbis, have been writing in this vein for a century. The problem is establishing the encampment, finding a willing audience for the symphony.

Jewish traditions may indeed have important things to say in the transhumanist future, but first we non-Orthodox Jews have to get there—as Jews. And doing so may require worrying less about, say, the nanotechnology of even the near future and more about the conscious practice of mitzvot and study of Torah in the present.

This is not to say that Schiff is wrong about the nature of the problems that liberal Judaism, indeed all Judaism, will soon face. When an AI chatbot is able to give a more deeply informed halakhic opinion than even the greatest rabbinic scholar, what becomes of a scholar-led book-centric tradition? Before you answer that question, please know that you do not know. None of us do. The great merit of Schiff’s book is that he forces us to confront such questions. In doing so, he has pushed the Jewish intellectual agenda both deeper and further.

Perhaps Rabbi Simon Greenberg was correct after all, but in a new way. Our task is not to explain the workings of America as a nation to its Jewish citizens, who no longer need such explanations. It is to explain how to navigate the brave new technological world America and other developed nations have made.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Michael Chabon’s Sacred and Profane Cliché Machine

What's wrong with "knocking down walls"? Well, several things...

Digital Anti-Semitism: From Irony to Ideology

From tweeting trolls to digital incitement, a contemporary history.

Double Lifers

In 2006, a blogger known as Baal Habos posted about a former rebbe who had once compared heretical media to “a hole in the head.” By then he had become a “ba’al ha-bos” (roughly, a family man), with a position in the community he wasn’t comfortable giving up, he had acquired plenty of holes in his head and wanted to discuss them—anonymously.

Between Literalism and Liberalism

While literalism is intellectually untenable and liberalism is numerically imperiled, many Jews find that what they believe cannot be transmitted, and what can be effectively transmitted they cannot believe.

Lawrence Block

The scholar—led book centric tradition will

not succumb to an AI chatbot, as most Torah commentaries and halakhic discourses are not, as yet, digitally accessible…

Richard Marpet

How do we reconcile this shift with growth of Jewish Day Schools. In 1971 Los Angeles there were about 500 students in (overwhelmingly Orthodox) Jewish Day Schools. Today it's closer to 10,00.

JJ Gross

Conservative Judaism is evaporating in real time because its entire ethos has been one of pandering to the least common denominator. It claims to be halakhic, yet its halakhic decision-making process became the mere rubber stamping as de jure what was already happening de facto. For too long now, the only practicing Jews in most congregations have been the rabbis and, maybe, their families. Ultimately being a congregational rabbi became the world's loneliest profession, and the dearth of interested candidates speaks volumes.

Among the Reform, an opposite trend is in place. The younger generation of rabbis are true leaders -- leading their flocks away from any meaningful engagement with Judaism. Like their mainline Protestant counterparts they specialize in emptying the pews by preaching a progressive intersectional ethos that has nothing to do with religion and even less to do with Judaism. As for Reconsructionism, the less said the better. What is replacing all of these movements in Chabad. Today - and especially since October 7th - Jewish magnet on the college campus is Chabad. Because the young crave genuine warmth and a place of love in a world gone cold and digital and, as we now see, antisemitic. As well, the young are drawn to authenticity, which they see in their Chabad rabbis and their wives and children. And while they, for the most part, have no desire or intent to live like their Chabad emissaries, they do have a desire to authenticate whatever elements of Judaism they will choose to practice. Chabad is THE Jewish success story of our time, proving that there is nothing anachronistic about a combination of nonjudgmental love and the sense of liberation that comes from feeling genuinely Jewish.