Berdyczewski, Blasphemy, and Belief

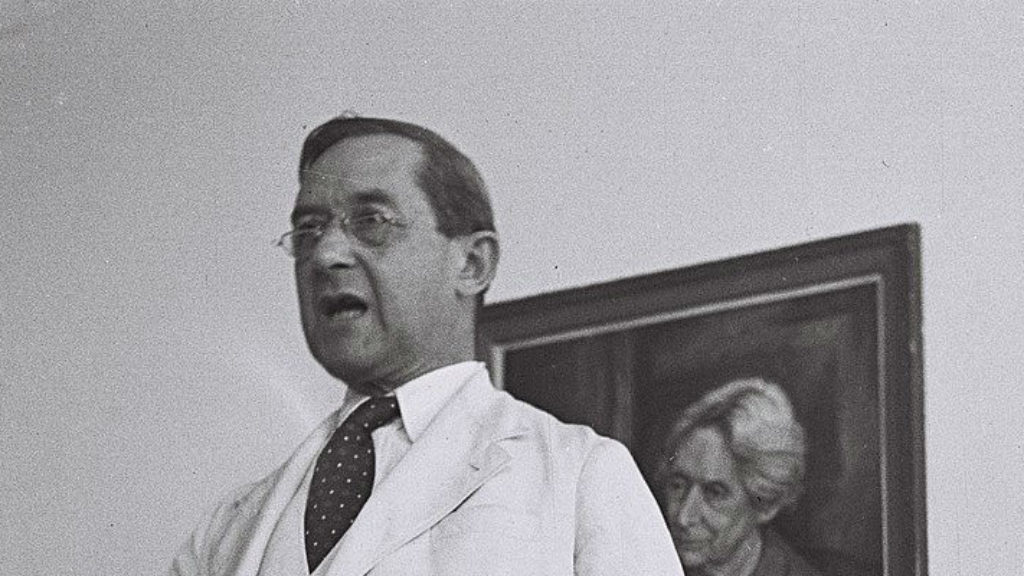

Micha Josef Berdyczewski (1865-1921), the son of a rabbi in the insular Hasidic community of Medzibezh, wasted no time in expanding his horizons. Already in his adolescence he dipped into such suspicious modern works as Nathan Krochmal’s Guide to the Perplexed of the Time. For that, at the age of 17, he paid a high price—the wreckage of his marriage prospects. But it was not until eight years later, after a period of study at the famous Volozhin yeshiva, that he broke with the world of orthodoxy altogether. After studying in Germany and Switzerland, he earned a Ph.D. in philosophy, but his enduring fame is due the novels and essays that he wrote mostly in the Hebrew language.

While other Hebrew writers of his generation sought either to modernize the Jewish religion or to translate its values into acceptably secular terms, Berdyczewski wanted to make a fresh start. He urged his generation to be not the “last of the Jews” but “the first of the Hebrews.” This would entail, in the Nietzschean language that he employed, a “transvaluation of values,” a departure of the Jews from the desiccated world of “the scroll” to the vital world of “the sword.” Propagating this message, Berdyczewski incurred the wrath of any number of contemporary rabbis—but not all of them.

In the excerpt below, we find a surprisingly sympathetic portrayal of Berdyczewski by one of the towering figures of the rabbinical establishment, Rabbi Yechiel Yaakov Weinberg (1884-1966). A prominent Torah scholar who would eventually head the famous Rabbinical Seminary of Berlin, Weinberg achieved recognition in the years following World War II as one of the world’s leading halakhic authorities. He was also an avid reader of modern Hebrew literature. Writing in Jeschurun, the journal of Berlin’s intellectual Orthodox, in 1921, Weinberg maintained that Berdyczewski’s strident opposition to traditional Judaism was at bottom more deeply religious than many people’s unreflecting adherence to it. Orthodox Jews could in fact learn something from him about the nature of religious faith and the struggle that characterizes its highest form. Weinberg presents what is not only an unusual example of Orthodox appreciation of Berdyczewski, but also a sophisticated portrayal of belief, one far removed from the popular presentation of religion as helpful in bringing about “peace of mind.”

He is a unique writer. One cannot find another who provokes so much bitterness and protest in the hearts of the pious. Before him, no one dared express such shocking heresy (apikorsut) as that which is sprung from his pen. His heresy strikes at the heart of the believer, leaving him dumbfounded. Such blasphemy no Jew has yet heard, and his impudence towards Heaven crosses all boundaries. Yet at the same time, no other writer is so close to a pure religious soul. He has no equal when it comes to penetrating the heart of the believer, touching its most delicate cords. Here you are angered at him, and there you follow after him. At times his rebellion against Heaven causes you pain, provokes your anger, and desecrates the Holy of Holies in your heart. You want to stamp your feet, grind your teeth, and scream at him: “Desecrator of that which is holy, Troubler of Israel!” Yet at the same time you feel yourself captivated by his charms. The pain and anger are sunk deep in your soul without you being able to express them verbally. You must hate him, but you cannot debase him; you want to place him under a ban, but you do not want to push him away.

Despite his poisonous pronouncements directed towards Heaven, you remain attached to him. With shame you are forced to admit: We have a spiritual connection and a closeness of hearts. What is the reason? It is because of a shared origin. The heresy of Berdyczewski is Jewish at its roots and branches. It arises from the same spiritual source from which the [Jewish] religion is nourished and supported—from the depth of spiritual yearnings and desires.

Belief and denial do not always oppose one another. There is belief that is itself denial—a man’s denial of himself, his negation of his essence, and his surrender of who he is. There is also denial that has in it an element of belief, and has nothing to do with arrogant abandon. For the latter is nothing more than throwing off the yoke of the Law.

Belief and denial do not always oppose one another. There is belief that is itself denial—a man’s denial of himself, his negation of his essence, and his surrender of who he is. There is also denial that has in it an element of belief, and has nothing to do with arrogant abandon. For the latter is nothing more than throwing off the yoke of the Law.

Belief that is tranquil and satisfied testifies to an inner emptiness and lack of thought. Shrinking in the face of powerful impressions for which one is not spiritually prepared drains one’s essence of its strength. A man is swept away, trapped by the external flow, which influences his senses. His will is broken and he cannot rise up or protest. He believes because he no longer has the strength to deny.

Belief such as this is not worthy of its name; it is merely a lack of disbelief. It cannot be a source for creativity. Perfect belief, worthy of the term, is both religious and creative, and it is by nature tempestuous. It comes from an abundance of strength and moral power. This type of belief is not a passive spirituality, but a forceful expression of spiritual activism that creates and conquers. It is not one that surrenders and is disciplined, but one that decrees and determines, demands and overcomes. Such belief does not arrive after denial has ceased in the heart of man and lost its vitality. Rather, it precedes denial, or arrives together with it, arising and sprouting from within it . . .

The Sages set forth a principle: There is no belief without denial, and there is no positive without negation. A true believer is also a partial denier (kofer). He bows to God and destroys the idol. With one hand he builds an altar and in the other he tears down a high place of idolatry. From this you learn that the great distance between the believer and the heretic looms large to the naked eye, which sees their outward form, but not to one who examines the matter closely, looking into the folds of their souls and the source from which they have been hewn. The Sages spoke of a true heretic, not one who simply throws off the yoke of the Law.

Berdyczewski is a religious heretic. His heresy was acquired not through casual reading of heretical literature, but through spiritual torments and great sacrifices. When we examine his oeuvre, we sense the difficult inner struggle, the convulsions of a grieving soul. Every one of his words is soaked in the essence of his blood. This is a true heretic, one who used to believe and now denies, who once had faith but has just seen it die before his eyes, and has witnessed its death-throes. This is an ethical heretic, a Jewish heretic, whose heresy is suffused with the spirit, which enlivens faith. He still stands at the well of religion, stirring it with his feet and muddying its water. At times he bows his head, drawing with his mouth, and quenching his thirst.

The unique pathos of Berdyczewski makes an impression on the pious reader. One senses immediately that this man has not assumed his place on the literary stage in order to “say his piece,” but has been powerfully prompted to do so by an inner force. The fire found in his bones ejects from his mouth sharp words that sting one’s soul. One senses that it is not from irresponsibility or arrogance that he says what he says.

Berdyczewski is not one of those writers who carefully measures all of his words. When he speaks he closes his eyes and sends down fire and brimstone. He does not concern himself with his listener and or with the latter’s most exalted religious feelings. What is he like at such a moment? A boiling kettle, bubbling over until its heat weakens. Berdyczewski, whose opinions are so far removed from religious Jewry, has a style and pathos that leaves the impression of a religious castigator, who stands at the gate and urges service to the Creator. It sometimes appears that even in his battle against religion there is a great deal of religiosity in him. It is not religion that is defective in his eyes, but the apathy of its adherents that repels him. Religion, whose first appearance in the world was marked by strength and courage, has become a sign of weakness, a place where old women can distinguish themselves.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

A Good Second Choice

Yirimiyahu be-Tzion is a solid work of intellectual history, devoted above all to understanding Judah Magnes as he understood himself, sympathetic but honest, and attentive to the weaknesses as well as the strengths of his thinking.

Total Eclipse of the Brakha

Do we make a blessing on a solar eclipse? Well, that depends if eclipses are evil or not.

Warped Fantasies

Jews observing the resurgence of anti-Semitism in the 21st century may be forgiven for thinking that they inhabit “a warped fantasy.”

Posthumous Prophecy

Milton Steinberg's unpublished novel about Hosea was forgotten for a long time. For good reason.

marcus

Substitute Bob Dylan for MYB--