What the U.S. Can and Can’t Do in the Middle East

The Obama administration’s lack of success in reviving negotiations between Israel and the Palestinians highlights a paradox. The US has a great deal of power in the Middle East, but it is often practically impotent.

How can this be?

The scope of American power, in the Middle East or anywhere else, depends on circumstances and local conditions. Yet Washington policy wonks all too often tend to overlook this uncomfortable fact, viewing situations exclusively from inside the Beltway.

Throughout the many decades of US involvement in the Middle East, there is a pattern of success as well as failure, and it is this pattern that constitutes the backdrop to the knowledgeable and timely new book by Dennis Ross and David Makovsky—the one a veteran of Mideast peace negotiations under several American presidents, the other a seasoned journalist and analyst.

The United States has been and can be extremely powerful and helpful when either of the following scenarios unfolds: 1) a shooting war erupts and threatens to unleash dire regional or even global consequences or 2) the contending parties have already made, on their own, significant steps towards reaching an agreement but still need a helpful push from the outside. In the first case, the US can function as an effective firefighter and bring about a cessation of hostilities. In the second, it can act as a midwife and help clinch the deal.

Examples abound. Let us start with the first scenario—stamping out conflagrations. Towards the end of October 1973, Israel had overcome the first shocks of the Egyptian and Syrian attack; its forces had crossed the Suez Canal, were about to encircle the Egyptian Third Army, and were positioning themselves on the highway to Cairo, at Kilometer 101. The Egyptian forces were in imminent danger of total collapse, threatening unforeseeable consequences for Egypt and the Arab world. The threat of direct Soviet intervention was on the horizon. Washington, for its part, did not want to see the Egyptians subjected to a crushing defeat, rightly thinking that future chances of Egyptian–Israeli rapprochement rested on the establishment of some sort of equilibrium between the two countries. Another humiliating Arab defeat like the one in 1967, it was presumed, would only make the Arabs more obdurate and the Israelis even more arrogant. The US resolved to put an end to the fighting and start a slow process of consolidation. It delivered the tough messages that stopped a victorious Israeli army in its tracks and started the uphill process of two disengagement agreements which eventually led, in their own circuitous way, to Israeli-Egyptian peace in 1979.

In the last stages of Israel’s invasion of Lebanon in 1982 (“The First Lebanon War”), after Syrian agents assassinated the Israeli-backed Lebanese President-elect Bashir Gemayel, Israel was about to burst into Muslim West Beirut. In all probability, this would have brought about a Syrian intervention in what until then had been a limited Israeli-PLO conflict. A few angry phone calls from President Reagan to Prime Minister Begin stopped Israel from occupying West Beirut and led to complex negotiations, which culminated in the PLO evacuating Beirut and relocating its headquarters to Tunis.

A structurally similar but somewhat different case unfolded during the first Gulf War in 1991. After the US military had failed to eliminate Iraqi missile launchers that had been used to dispatch thirty-nine missiles against Israeli civilian targets, Israel considered a major operation against Iraq. Washington feared that this might break up its coalition with moderate Arab states (mainly Saudi Arabia) against Saddam Hussein, and warned Israel that should it launch such an operation, its planes might find themselves confronting US aircraft, or at least denied the codes necessary to fly over American-controlled airspace. The Israeli government under Yitzhak Shamir—a hard-liner if ever there was one—gritted its teeth but gave up on attacking Iraq.

What all these scenarios have in common is simple: the situation was combustible, and what was required of Israel was only a cessation—or avoidance—of a set of military operations. America exerted intense pressure to make Israel stop on a dime. No lengthy processes were involved; a clear “Yes” or “No” was required from Israel immediately (with a “No” obviously ruled out).

There have been other occasions, however, when Israel and its adversaries have started negotiations on their own, made significant concessions to each other, and borne the domestic political costs of their decisions. But then, at the last minute, their failure to resolve some final disagreements bilaterally threatened to destroy the whole edifice of negotiations. In such situations, an assertive American intervention in the negotiations has been proven to be immensely powerful and successful.

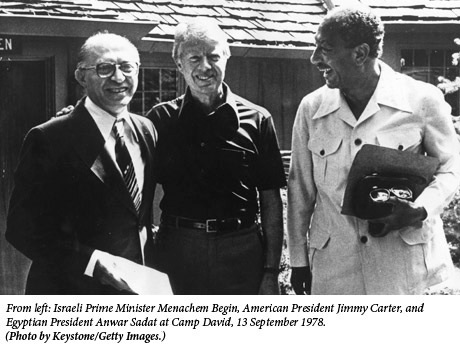

When President Anwar Sadat, for instance, decided to travel to Jerusalem and address the Knesset, his initiative caught Washington by surprise and was seen by the Carter White House as potentially undermining its own hitherto unsuccessful attempts at peacemaking. Hawkish Prime Minister Menachem Begin’s surprisingly generous response led to a year of largely successful bilateral negotiations between Israel and Egypt that brought the two countries to the brink of peace. Yet a few thorny issues still remained unresolved. Both sides found it difficult to make the necessary final concessions. It was at this time that President Carter called the leaders of both countries to Camp David, knocked heads together and used the carrot as well as the stick to make both sides go the extra inch to reach an agreement, which was then celebrated on the White House lawn. Nevertheless, there was historical justice in awarding the Nobel Peace Prize to Sadat and Begin, but not to Carter. The American president had been merely the helpful midwife while parenthood belonged exclusively to the leaders of Egypt and Israel.

A similar scenario unfolded in the 1993 negotiations between Israel and the PLO. Again, the Oslo negotiations were initiated by the two sides, with the US left completely out of the loop and even angry at Israel for starting such a momentous process without divulging it to its major ally. While the secret bilateral negotiations in Norway brought both sides towards the historic achievement of mutual recognition, they were unable to resolve a number of tricky issues. It was at this point that President Clinton got into the act, invited Rabin, Peres, and Arafat to Washington and was able to tighten the loose knots. Again, the US was a midwife, not the initiator or the mediator: what Israel and the PLO did achieve, they achieved—except for the extra few inches at the final moment—bilaterally and on their own.

The Israel-Jordan peace treaty of 1994 was likewise negotiated bilaterally (again, with some American misgivings), but the final photo opportunity at the signing at the Arava Crossing in the desert featured President Clinton, who gave his blessing to an agreement reached directly between King Hussein and Prime Minister Rabin.

The US can, then, be of assistance. But when a shooting war or bilateral negotiations are not already underway, it falls flat on its face. Every American attempt to reach an agreement in the absence of these conditions has ended in spectacular failure: the Madrid Conference fizzled out into jejune and futile committee meetings; President Clinton’s attempt at Camp David 2000 to bring Prime Minister Barak and Chairman Arafat to sign a peace agreement failed dismally; President Bush’s Road Map remained a wish list and his last minute Annapolis Process turned out to be a nice photo opportunity. President Obama’s attempt to dispatch his special representative former Senator George Mitchell already appears to be an exercise in futility.

The reason for this is simple: in the absence of a political will on the part of the local players, an American president cannot bring recalcitrant horses to water. Even if both sides sign a framework agreement, like the Road Map, the test is in implementation, and the devil, as always, is in the details. There are hundreds of details involved in any Israeli-Arab agreement (see the Egyptian-Israeli peace treaty or the Oslo Accords). Carrying out any such agreement, which entails territorial issues, possible population evacuation, and complex security arrangements with a plethora of technical arrangements, takes years. An American president cannot constantly babysit such a protracted process, nor can he oversee all its details on a daily basis (he has, after all, other issues on his plate). Without the necessary preconditions, the process invariably gets bogged down in the eternal and treacherous dunes of Middle East politics.

Ross and Makovsky have very different backgrounds and perspectives, but they are both veteran Middle East experts who are well aware of the checkered record of the world’s greatest super-power in the region. The failure of the Bush Administration to bring about democratization in the Arab world as a consequence of the defeat of Saddam Hussein adds to the bitter aftertaste of good intentions gone sour. Yet the authors are equally troubled by the way some of Bush’s critics—as exemplified in the Baker-Hamilton report—view the Middle East and America’s options in crafting an alternative policy. This brings them to the conclusion that grand theories about the region—be they of the right or the left—fail to resolve its problems. At the root of such theories, regardless of their ideological bent, lie a number of basic myths and illusions. It is this set of myths and illusions that the authors set out to discuss, analyze, deconstruct—and sometimes pillory—as responsible for many of America’s missteps and failures over the years. By their account, realists and neoconservative idealists alike are guilty of imposing theoretical constructs upon a recalcitrant reality. Worst of all, Ross and Makovsky remark, realists can sometimes appear to be ignorant of reality.

The authors focus mainly on three myths: 1) “linkage,” 2) “engagement,” and 3) promotion of regional democracy. The connection of the first two with the supposedly innovative approaches put forth by the Obama administration (in which Ross himself now plays a part) is what gives this book its special significance.

Ross and Makovsky view the myth of linkage as the most pernicious of the three, and call it “the mother of all myths.” They show that it is not really new, and that the “realists” who currently espouse it have a venerable lineage, going back to the 1940s. According to this “realist” view, the problems that the United States faces in the Arab world—and by implication also among Muslims in general—stem from the Arab-Israeli conflict. Once this conflict is solved—and solved, so the proponents of this approach usually, though not universally, suggest—by satisfying Arab demands, the tension between the Arabs and the US will disappear. In political terms, what this has meant for decades is that Washington must compel Israel to dismantle all settlements and return to its pre-1967 borders. The subsequent establishment of a Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital would at once put an end to the estrangement of the Arabs from the US, enhance the standing of America in the region, and (realists being realists) insure an unimpeded flow of oil from the Arab Gulf states to the West. Waxing sanctimonious, some of these realists occasionally add that this would also be in Israel’s “best interests.”

This myth was initially identified with basically conservative groups, business-oriented, sometimes connected with oil interests, and ensconced among the State Department “Arabists.” Occasionally, it was also tinged with strains of genteel anti-Semitism, viewing Jews generally (in American society, as well as in the Middle East), as slightly pushy and disruptive of the established order. It was these “realists” who sought unsuccessfully to thwart President Truman’s recognition of Israel in 1948. At that time, some even viewed the social democratic dominance of the Jewish community in Palestine as being a dangerous prelude to Soviet influence on the politics of the Jewish state.

The right-wing tincture of the “realists” has faded in recent years, and this position is now much more identified with a left-wing approach (how “realists” can really be left-wing if left-wing politics is identified with universalist humanist ideas is a separate issue). Not to put too fine a point on it, this attitude was also, at least in part, responsible for President Obama’s masterful—yet fawning—speech in Cairo.

Ross and Makovsky go to great lengths to show how this linkage theory is faulty, both factually and historically. The authors identify some of the bloody conflicts in the region that have nothing to do with Israel, from the Iraqi coup of 1958 to the Yemeni civil war of 1962-68 to the 2003 Iraq War. Moreover, the major challenge to American regional and world hegemony—the tragedy of 9/11—was initially depicted by al-Qaeda itself as a response to the subversive influence of America on Arab and Muslim lifestyles, mainly in Saudi Arabia. Only much later did the Palestinian issue appear in Osama bin Laden’s fatwas.

The claim that failure to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may embroil the whole area in ever-widening violence and instability has been—at least until now—belied by the facts. The second intifada, for all the support it gained on the “Arab street,” mainly due to Al-Jazeera TV, had little effect in neighboring countries or influence on their relations with the US. No doubt the Palestinian problem and Israel’s occupation of the West Bank (and until 2006 also of Gaza) have added a further element of tension to the area. But it is the “root cause” of neither the region’s instability nor its frayed relations with the US.

The linkage theory has served over the years as a convenient vehicle for the Arab countries’ public diplomacy. Rather than address internal issues of repression, discrimination, authoritarianism, and economic stagnation, it is much easier for Arab rulers—be they monarchist or republican, but in every case non-democratic—to pin all their problems on “the conflict.” This is the best alibi for deflecting local criticism as well as avoiding the kind of inner reforms they so desperately need. The authors mention the courageous UNDP 2002 Arab Human Development Report, written by Arab intellectuals and experts, which states expressly that “[Israeli] occupation has damaging side effects”—but avoids portraying the occupation as the cause of Arab underdevelopment in the areas of education, women’s rights, general human rights, democratization, and liberalization. The attempt to blame Israel, and the conflict, for all the ills of the Arab world is another example of a culture of victimization which is endemic to the Arab world though not unique to it (the Israelis have their own version), and makes the chances of reform in the region even more remote.

Ross and Makovsky also point out that the “realists” choose to overlook the reality and depth of the fundamental Arab unwillingness to accept the Jewish state. This is a deeply felt ideological tenet of Palestinian and Arab historical narratives, and though Egypt and Jordan have found it possible to make peace with Israel by skirting the issue, their populations still adhere to this worldview. The problem is not just the post-1967 occupation of Palestinian territories, but goes much deeper. For “realists” to ignore this is simply unconscionable and certainly renders it impossible for them to provide a realistic map of the situation.

Sticking to the linkage myth will, according to the authors, impede any progress towards peace in the region. The tepid response—to say the least—of Arab countries to Obama’s soaring rhetoric in Cairo suggests that while most Arabs welcomed the President’s non-confrontational approach, they did not feel that it is incumbent upon them to reciprocate.

The authors are equally scathing in their assessment of the neoconservative myth of democratization, but the collapse of this myth in the wake of the second Gulf War has obviated the need for extensive refutation. What is not always explicitly stated, even by an Obama Administration eager to get out of Iraq, is that what the US will not leave behind is a democratic regime. If Iraq does not descend into civil war when the American forces depart, it will be because a neo-authoritarian regime will have consolidated its power in Baghdad. What will happen then to the de facto semi-independent Kurdistan Regional Government does not seem to bother either “realists” or liberals. That the Kurds were the most oppressed group under Saddam and also the US’s best (and only real) ally, does not seem to bother all those who—justifiably—call for the Palestinians’ right to self-determination. Some peoples are obviously more equal than others.

Towards the end of the book Ross and Makovsky tackle the myth of “engagement,” and here their account is most nuanced. While they are not altogether opposed to engagement, especially with Iran, they have serious doubts about Hezbollah and Hamas. On an intellectual level, nobody should be against engagement. This is especially the case when one takes into account, as the authors repeatedly do, that the confrontational approach of the Bush Administration did not stop Iran from proceeding along the road to nuclear development. Yet Ross and Makovsky are skeptical as to whether the adoption of engagement as such will solve the dilemmas posed by Iran’s nuclear ambitions. Developments in recent months seem to prove them right.

The authors propose a number of possible options, but favor a novel approach. Rather than negotiate with Iran in open forums, they suggest opening a secret back channel (the real “realist” Kissinger option). This should be accompanied by a robust policy of supporting, politically and militarily, Iran’s antagonists in the region. What they recommend is in essence a sophisticated carrots-and-sticks policy, but without the public fuss that accompanies open negotiations. It is better for the participants to talk to each other than to CNN. Such back-channel talks should suggest to the Iranians not only the benefits of an agreement, but could also spell out—in grim detail, made possible by secrecy—the dire consequences if an agreement were not to be reached.

This looks and sounds reasonable. But is it perhaps too late for such an approach? Is the current internal turmoil in Iran (which has escalated since this book was published) making such a scenario virtually impossible? These are difficult questions, and in any case there is no doubt that the US needs a sophisticated policy of engagement also with its European allies if it envisages an effective “coalition of the willing” in case the current engagement leads nowhere.

The authors try to reintroduce realism into US policy in the region, but realism based on reality, not on abstract constructs. They also argue that the administration should carefully nurture reform in the Arab world—and they identify some of the more prominent reformers who should be encouraged. But this should be done without undermining existing regimes, realizing this is a long-term process, not a deus ex machina. After all, Bush’s insistence on Palestinian elections granted Hamas not only a plurality but also quasi-democratic legitimacy. Pushing for peace should also be accompanied by a measured assessment of what is feasible, as opposed to a pipe dream, even if it looks nice on paper. Hence, conflict management rather than conflict resolution should be seriously considered—after all, this has been the approach in Cyprus, Bosnia, and Kosovo after more ambitious peace plans have failed.

There is an obvious subtext to all of this: aside from telling a political story, the authors also maintain that the claim that the US should “distance” itself from Israel, and thus regain its standing in the Arab world, is wrong-headed. It is a timely reminder, bolstered by sound historical knowledge and understanding of the region.

The book’s value is enhanced by the fact that both authors are “doves”: they believe in a two-state solution and find the Israeli settlement policies unconscionable on both moral and political grounds. In the past, Ross has sometimes been accused by Israeli negotiators of being “pro-Palestinian.” But being dovish does not mean being starry-eyed or ignorant. Therein lie wisdom and moderation.

Suggested Reading

Belt, Road, and Risk

When Prime Minister Netanyahu visited the White House in 2019, President Trump was said to have put the same point more bluntly: Washington’s security will be compromised if Jerusalem and Beijing grow too close.

Politics and Anti-Politics

Michael Walzer asks new questions of the biblical text, the same sorts of questions we often ask of Locke or Voltaire.

Rallying Round the Flags

Derek Penslar's new book returns to aim Jewish soldiers of the diaspora to their rightful place in Jewish history.

Foundation Stone

The meshichists remove the covering from Schneerson's red velvet chair because he will be sitting on it during prayer; they gaze at the spot where he is believed to be stationed; and they call him up to the Torah for aliyot, parting ways to make room for him as he “walks” up to the bimah.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In