Foundation Stone

On June 12, 1994, Menachem Mendel Schneerson, leader of the Chabad Lubavitch movement, died. His death shook the Chabad community, which, under his leadership, had grown to become a billion-dollar global outreach enterprise. Its astronomical growth from what was basically a Hasidic neighborhood in Brooklyn to a dominant force of contemporary Judaism was premised on a belief, cultivated and fortified by Schneerson, that the messiah’s coming was imminent.

Growing up in a Chabad family, I was alerted to Schneerson’s death when I heard my mother break down in sobs in her bedroom. She was pierced with pain at the news that she had lost her mentor, her teacher, her messiah. It was not long, however, before I learned from my mother that the “Rebbe has not died,” that he continued to live among us even more than he did before. That statement, and the fervency with which it is believed by many Lubavitchers, is Yoram Bilu’s title to his gripping and carefully researched new book, With Us More Than Ever. The book’s subtitle, Making the Absent Rebbe Present in Messianic Chabad, captures how my mother and many like her have transformed their pain over Schneerson’s death into various “media” by which they creatively construct a reality according to which he is in some ways more alive than ever.

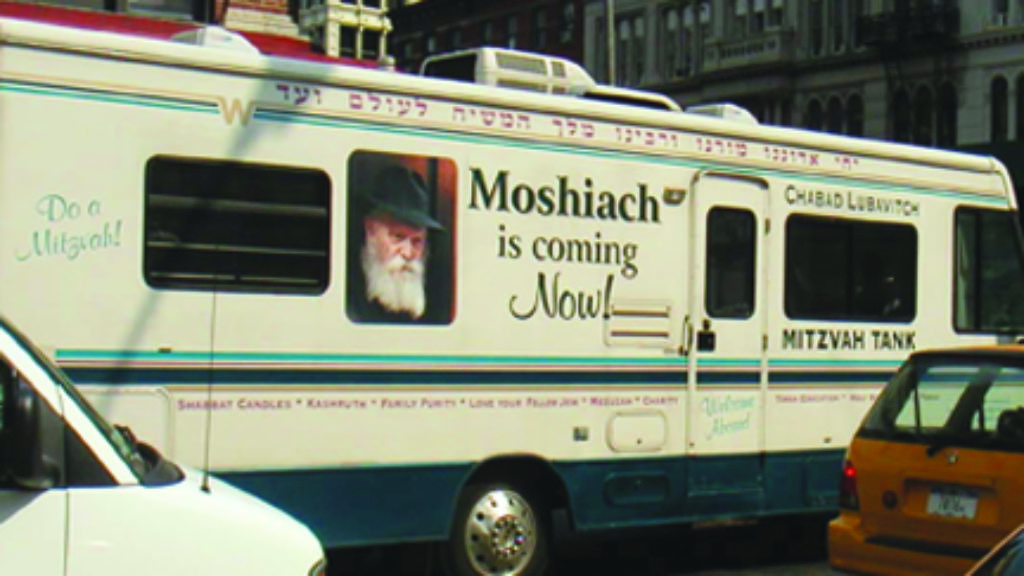

Chabad is known for its outreach. For some, that means a young man on Madison Avenue invasively asking passersby if they are Jewish; for others, it is the warm young couple in Missoula, Montana, providing free bar mitzvah lessons; for still others, often Modern Orthodox families on vacation, it is the convenient kosher Shabbat meals offered in Venice, Italy, or a California beach town. To most, though, Chabad resembles what we might call “Hasidism-lite”—with all the advantages of “authentic, traditional” Judaism minus the off-putting isolationism and rejectionism of most other Hasidic sects. While teaching a Jewish adult education course in New York, I asked my students whether they felt more kinship with non-Jewish European tourists or the Hasidim on Forty-Seventh Street. The class unanimously chose the former. But when I refined my question and asked whether they felt more kinship with Chabadniks in particular, my students’ faces lit up. Chabad rabbis, they felt, are like other rabbis, including Hillel rabbis who often hail from the Conservative and Reform movements; they just happen to wear beards, cool fedora hats, and genuinely inclusive smiles.

Bilu’s book provides a different image of Chabad, or at least one segment of it. His book “focuses on the experiential world of ordinary and marginal Hasidim,” those he calls radical messianists. Bilu doesn’t say how many Chabad Hasidim are radical messianists, but his impression is that they make up only a small, outlier subgroup within the broader Chabad movement. It is possible that many, if not most, Chabad Hasidim believe that Schneerson will prove to be the messiah in some sense (though it is impossible to say just how many). The radicals, however, work hard to ensure that even before he redeems the world from its current state of exile and re-presents himself in the flesh and blood for all to see, the Rebbe remains palpably present. They write letters to him, slipping them between pages of his collected correspondence, and then divine his answer from the words on the page; they fill their homes with pictures of Schneerson so that his gaze is almost always upon them; they make pilgrimages to 770 Eastern Parkway, Chabad’s headquarters and Schneerson’s synagogue, where Schneerson is imagined to still be physically alive. By studying these Hasidim, Bilu shows how the capacity to maintain “the sense that [Schneerson] continues to live among them” is realized.

The central claim Bilu promotes is indisputable: a segment of Chabad engages in a wide range of practices by which they manage, every day and much of each day, to connect to a Rebbe who died over two and a half decades ago. Anthropologically, this is uncontroversial, but Bilu’s unwavering focus on lived experience while ignoring its theological basis does his otherwise fascinating study a disservice. His assumption that the theological and anthropological dimensions of Chabad can be neatly disentangled is misplaced.

Although Bilu sporadically describes meshichists’ (messianists’) beliefs and practices as “revivals” of ideological currents that were already present in Chabad, the thrust of With Us More Than Ever gives the distinct impression that most if not all the practices Bilu documents are inventions of the last two and a half decades. His focus “is not the classic Chabad movement and its theosophy, nor the messianic teachings of the last Rebbe, but rather the means that his followers developed in the past generation to make the Rebbe manifest in their world.” His focal point is the behavior of meshichists. To the extent he touches on theology, it is the beliefs of the meshichists, most of which he also portrays as inventions since Schneerson’s death.

To grant that behaviors alone can be studied, divorced from theology, one has to accept that the two are separable in the first place. But what if many of the practices Bilu records are attributable not only to the desire to feel personally connected to the Rebbe but also to the power of theology and the need for theological consistency?

For example, Bilu describes in great detail the various rituals radical messianists engage in at the synagogue in Chabad headquarters, which is known simply as 770. They remove the covering from Schneerson’s red velvet chair because he will be sitting on it during prayer; they gaze at the spot where he is believed to be stationed; and they call him up to the Torah for aliyot, parting ways to make room for him as he “walks” up to the bimah. Bilu’s explanation of these behaviors as inventions to make an absent Schneerson feel present to his followers is convincing. But it elides another explanation: that devotion to Schneerson’s teachings compels these behaviors.

Schneerson’s teaching about the messiah and his not-so-subtle suggestions that he was the redeemer for which Jews have prayed for millennia date back to the very first day he assumed the mantle as Chabad’s seventh leader in 1951. Schneerson would often refer to his predecessor and father-in-law, the Frierdiker Rebbe (previous Rebbe), as the nasi hador, the prince of the generation, thus implicitly describing himself as the next one. A nasi hador is not just the leader of a single Hasidic sect but the leader of world Jewry, and, indeed, the world writ large. Many consider Chabad to be hubristic because of its aggressive outreach, but it is important to remember that blaring Mitzvah Tanks and Chabad Houses in the farthest corners of the world are the institutional expressions of a theological doctrine. Schneerson taught, and Chabad Hasidim continue to believe, that Chabad’s seven leaders—starting with Schneur Zalman of Liadi, its founder, up until its final leader, Schneerson—were (and in Schneerson’s case still are) the prince of the generation for all Jews, indeed, for all humans. The nasi hador is the even hash’tiya (founding stone) of the world, what scholars of religion have called the axis mundi (world axis). In short, without him, the world could not continue to exist since the divine energy that sustains the world at every moment is channeled through the Rebbe.

Elaborating on a rabbinic saying that the foundation stone is buried but extant, Schneerson taught that the same was true of the nasi hador:

Just as the world’s foundation stone must be present in some place in the physical world, and it persists continually without any changes or ever changing—not even the “change” of burial, similar to the holy ark and the like—so too the judge and prophet must exist in a continual way in every generation . . . as the world’s existence is founded on him.

Taking this and similar teachings seriously and engaging in a bit of deductive reasoning, the “radical” messianists argue that Schneerson must be physically alive still today because the world still exists.

The idea that a man of ninety-two years who was ailing, died, and was buried in a Queens cemetery somehow continues to remain physically alive is indeed radical. But, arguably, it is not any less radical than countless other beliefs Hasidim, including Chabad Hasidim, have about their Rebbes, for instance that they are capable of interfering with nature and performing public miracles. It is, for instance, common knowledge within Chabad that the Rebbe redirected the course of Hurricane Andrew in 1992. Given Schneerson’s abundant teachings about the role of the Rebbe, it should not come as a surprise that there are Chabad Hasidim who today believe he is still physically alive or even that he has divine status. And yet it does come as a surprise to Bilu, who consistently refers to meshichists’ beliefs as astonishing and in need of explanation—which Bilu happily provides in anthropological terms by describing practices that “make the Rebbe more present,” without ever touching on the theological foundation stone upon which such practices are built.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

The Chabad Paradox

Despite its tiny numbers, the Hasidic group known as Chabad or Lubavitch has transformed the Jewish world. Not only the most successful contemporary Hasidic sect, it might be the most successful Jewish religious movement of the second half of the twentieth century. But two new books raise provocative questions about it.

Publishing Godliness: The Lubavitcher Rebbe’s Other Revolution

Much of the discussion of the Rebbe's legacy focuses on his charisma, his saintliness, and his organizational skills, but first and arguably foremost, he was a book publisher.

The Alter Rebbe

In Immanuel Etkes's new biography, we meet the young Shneur Zalman shortly after the death of his master Rabbi Dov Ber Friedman, known as the Maggid (or preacher) of Mezheritch in 1772.

President Grant and the Chabadnik

In 1869, President Grant received an unexpected visitor at the White House: Haim Zvi Sneersohn, a flamboyant and eccentric Chabad emmisary from Jerusalem. Bedecked in what The New York Times described as an "Oriental costume" consisting of a "rich robe of silk, a white damask surplice, a fez, and a splendid Persian shawl fastened about his waist," he strode self-confidently toward the president. Grant instinctively rose to greet him.

Joseph Newfield

Zalman is correct; Professor Bilu shies away from the underlying messianic theology within Chabad circles. Then again, Bilu is an anthropologist, not a theologian. As such, he tries to stay within his lane. For those wishing to learn more about Chabad Messianism, my recent essay in the HDS Bulletin on this topic will be informative. https://bulletin.hds.harvard.edu/after-the-death-of-chabads-messiah/