100 Years of Solicitude: Commemorating Balfour

“We are proud of our pioneering role in the creation of the State of Israel. We are proud to stand here today together with Prime Minister Netanyahu and declare our support for Israel. And we are proud of the relationship we have built with Israel.” So British Prime Minister Theresa May assured guests at the Balfour centenary dinner, hosted by the current Lords Balfour and Rothschild. Indeed, her November 2017 speech contained much to cheer the predominantly Jewish, and Zionist, audience. She advertised the growing economic links between Britain and Israel, stated her commitment to Israel’s security, condemned efforts to delegitimize Israel, and spoke about the new

Holocaust memorial under construction alongside the Houses of Parliament. So far, so crowd-pleasing.

But Britain’s relationship to Israel, and to her own history in the Middle East, is rarely that comfortable. Despite rejecting the Palestinian Authority’s demand for Britain to apologize for the Balfour Declaration, May was at pains to emphasize that there was still “unfinished business,” since Balfour’s “fundamental vision of peaceful co-existence has not yet been fulfilled.” As has become customary in any British government statement relating to Israel, the prime minister reiterated her dedication to a two-state solution and her opposition to the construction of settlements beyond the Green Line. In his statement on the Balfour centenary to the House of Commons, Foreign Secretary Boris Johnson also spoke of “unfinished business.” Evidently, the official line was to celebrate the declaration, but not without qualification.

Speaking in response, Netanyahu was gracious to his hosts, praising May for “keeping Britain on the right side of history.” Yet he did not shy away from challenging Britain’s historical propensity to hedge its bets. Noting Britain’s “painful retreats” from the Balfour Declaration during the Mandate, Netanyahu recalled that it had remained unfinished business for the Jews, too. The real tragedy of the Balfour Declaration, he said, was that its fulfilment came three decades too late for the Jews of Continental Europe: “Some people mistakenly believe that there is an Israel because of the Holocaust. In fact, it’s only because there was no Israel that the Holocaust could occur.”

If Anglo-Zionist relations have not always been easy, they could soon be much worse. The elephant in the room—or rather outside it—was Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the Labour Party, who refused to attend the dinner. A patron of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign who has previously referred to his “friends in Hamas and Hezbollah,” Corbyn is the kind of radical leftist until recently considered anathema to mainstream British politics. But these are unusual times. If his election as leader of the Labour Party in late 2015 surprised pundits, his narrow loss in the 2017 snap elections—during which a 25-point Conservative lead in the polls largely eroded over the space of seven weeks—provoked widespread disbelief in the country at large and disquiet in the Jewish community.

Corbyn’s excuse for not attending the Balfour celebration was that he “doesn’t do dinners.” Yet, in the same week, he found time to attend an evening reception in the House of Commons hosted by Muslim Engagement and Development (MEND), a charity with Islamist connections dubious enough for most other members of Parliament to give the event a wide berth. Labour was represented at the Balfour centenary by its shadow foreign secretary, Emily Thornberry, but she was clear that her attendance should not be understood to imply endorsement. Asked about the centenary in a recent interview, Thornberry replied, “I don’t think we celebrate the Balfour Declaration,” adding that “the most important way of marking it is to recognize Palestine.” Had Labour won in June, there may have been no official celebration.

The recent controversy over the celebration of the Balfour Declaration’s 100th anniversary is a microcosm of Israel’s place in British politics. Indeed, the centenary has fallen at a potential inflection point in Anglo-Israel relations. By British standards, the governments led by Prime Ministers Cameron and May over the past seven years have been particularly sympathetic to Israel. Quickly abandoning the critical-friend posture he had adopted at the start of his premiership (notoriously, he described Gaza as a “prison camp” during a visit to Turkey in 2010), Cameron emerged as a vocal ally of Israel. During both Operation Pillar of Defense in 2012 and Operation Protective Edge in 2014, Cameron stood firm in his support of Israel’s right to self-defense against rocket attacks from Gaza, defying not merely a well-organized pro-Palestinian lobbying campaign but also Liberal Democrat members of his coalition government.

Ruling alone since 2015, the Conservatives have been emboldened to go further. In February 2016, taking a lead from several American states, the second Cameron administration introduced new guidance to prevent boycotts of Israel by public bodies in procurement contracts (though this has since been partially overturned by the High Court). May has continued in the same vein. In December 2016, the United Kingdom became one of the first countries to adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s definition of anti-Semitism, which includes “targeting the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity.” In March 2017, the British delegation put the UN Human Rights Council “on notice” over its bias against Israel, warning, “If things do not change, in the future we will adopt a policy of voting against all resolutions concerning Israel’s conduct in the Occupied Syrian and Palestinian Territories.”

But this high-water mark of official British support for Israel still falls short of mainstream positions in American politics. President Obama’s refusal to veto Security Council Resolution 2334, which condemned Israeli settlements including those in East Jerusalem, was widely perceived as a vindication of Palestinian attempts to internationalize the conflict, and a nadir in U.S.-Israel relations. Yet Britain voted for it. While some reports have attributed Britain’s support for the resolution to a mistake by a junior minister, it was in fact consistent with government policy.

The fear of appearing too close to Israel affects more than British policy on settlements. Less than a week after the Balfour centenary, a diplomatic scandal involving senior Israeli officials precipitated the resignation of Secretary of State for International Development Priti Patel. One of the most outspoken supporters of Israel in the Cabinet, Patel had apparently been meeting Israeli ministers, including Netanyahu, behind the foreign secretary’s back, while formally on vacation. Somewhat farcically, she was flown back from a mission to Africa to be dismissed. But the official version of events was soon called into question. The Jewish Chronicle, citing sources in Downing Street, reported that Patel’s unofficial diplomacy in Israel took place with the consent of the prime minister, who had asked her not to disclose the meetings. The truth of the matter remains unclear. But would a breach of diplomatic protocol involving another country have provoked the same response?

Priti Patel’s exit from the Cabinet reflects the wider weakness of the current government. Shell-shocked by a failed election gamble which cost her party its majority in Parliament, Theresa May has struggled to regain her authority and to resolve internal disagreements over Brexit in the Cabinet. Were the government to fall, and another election to ensue, the polls point to a Labour victory.

A win for Corbyn, the most left-wing Labour leader in more than 30 years, would radically reverse Britain’s approach to the Middle East. Yet Labour has not changed its spots overnight. Since Tony Blair’s resignation in 2007—in part precipitated by his defense of Israel’s 2006 campaign in Lebanon—the party has continually moved to the left in both domestic and foreign policy. Ashamed of the last Labour government’s backing for the Iraq War, Corbyn’s predecessor, Ed Miliband, effectively vetoed any British military intervention against Bashar al-Assad.

The party’s policy on Israel was by no means exempt from this leftward shift. In contrast to Cameron, Miliband condemned the IDF during Operation Protective Edge. Two months later, he whipped Labour MPs to back a nonbinding parliamentary motion on the unilateral recognition of Palestine. Whether or not Corbyn makes it to 10 Downing Street, its next Labour occupant is likely to be far less friendly toward Israel than any prime minister since Ted Heath in the early 1970s.

This prospect poses a dilemma for British Jews, whose own relationship with Zionism has evolved significantly over the past century. While the Zionist group led by Russian-born immigrant Chaim Weizmann included several influential figures in the Jewish community (Israel Sieff, Simon Marks, Leon Simon, and Harry Sacher among them), high-profile Jews were also among the most ardent opponents of the Balfour Declaration. On learning that Britain planned to endorse a Jewish national homeland over the summer of 1917, Edwin Montagu, the newly appointed secretary of state for India and the only Jewish member of the Cabinet, circulated a memo “on the Anti-Semitism of the Present (British) Government.” His opposition to Zionism arose from the fear that the establishment of a Jewish state would leave Jews who remained in the diaspora susceptible to the charge of dual loyalty:

But when the Jew has a national home, surely it follows that the impetus to deprive us of the rights of British citizenship must be enormously increased. Palestine will become the world’s Ghetto. Why should the Russian give the Jew equal rights? His national home is Palestine.

Montagu was not alone in objecting to the Balfour Declaration. The dispute in the Cabinet was mirrored in the institutions of Anglo-Jewry. Important members of the Board of Deputies of British Jews (initially) and the Anglo-Jewish Association opposed the Zionist project, while Chief Rabbi Joseph Hertz and the Jewish Chronicle supported it. The final text was, in fact, a compromise, which reflected Montagu’s objection in its insistence that “nothing may be done which may prejudice … the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.”

By comparison to its forebears, modern Anglo-Jewry is much less divided with regard to Israel. Balfour 100 commemorations have filled the communal calendar over the past year. The sense of estrangement from Israel, palpable in parts of progressive American Jewry, is notably less pronounced among British Jews. Indeed, in recent years, they have demanded more vocal support of Israel from the Jewish leadership. Much as the Jewish Chronicle inveighed against the aristocratic Board of Deputies a century ago, a public backlash against the modern board over its muted response to criticism of Israel during the 2014 Gaza conflict provoked a more robust pro-Israel stance thereafter. Jonathan Arkush, president of the Board of Deputies since 2015, pulled no punches in his reaction to the United Kingdom’s support for Resolution 2334, calling the Security Council’s decision “a disgrace” at a public rally against it. He was similarly forthright in his support of Israel’s refusal to allow Hugh Lanning, chair of the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, to enter the country, stating: “If the Palestine Solidarity Campaign wants to avoid being treated like a pariah, it has to stop behaving like one.”

The importance of Israel to British Jews helps explain the dramatic recent shift in their political allegiances. Just prior to the 2010 election, a survey of Jewish voters suggested an even split between Conservative and Labour, with each party claiming 30 percent. By 2015, with Miliband leading Labour, similar research found that 67 percent of Jews intended to vote for the Conservatives, compared to just 14 percent for Labour. In 2017, faced with the prospect of Corbyn becoming prime minister, that gap had widened to 77 percent for the Conservatives and 13 percent for Labour—such that, in an election where the Conservatives lost seats in the capital, constituencies with high Jewish populations in north-west London conspicuously stood out as blue islands in a sea of red.

Jewish nervousness about a Corbyn premiership relates not just to his record on Israel, but also to his apparent indifference to anti-Semitism within his party. Offenders have been merely suspended from the party, rather than expelled. These include the former mayor of London Ken Livingstone, who has repeatedly insisted that there was “real collaboration” between Zionists and Nazi Germany prior to World War II, and Jackie Walker, former vice-chair of the pro-Corbyn campaign group Momentum, who, in a discussion of the Holocaust on her Facebook page, wrote that Jews were among “the chief financiers of the sugar and slave trade.” An internal inquiry into anti-Semitism, which found no evidence of it, was widely dismissed as a whitewash. Corbyn subsequently rewarded its author, Shami Chakrabarti, with a seat in the House of Lords and a position in the Shadow Cabinet. Given Corbyn’s prior record as an apologist for anti-Semitic conspiracy theorists and terror sympathizers, expectations of leadership from him on this issue were low. He has not exceeded them.

If Jews are becoming personae non gratae within Corbyn’s Labour party, the question arises as to what kind of climate he would foster as prime minister. As yet, there has been no widespread Jewish emigration from Britain to Israel, as there has been from France—in part, because British Jews have not been targeted by thugs and terrorists in the same way as their French counterparts have. But might a Corbyn government precipitate a comparable exodus?

Thankfully, Edwin Montagu’s fears about the status of Anglo-Jewry in the wake of the Balfour Declaration have proven largely unfounded over the last 100 years. Nonetheless, it is not impossible that British Jews may come to thank Arthur Balfour for providing them with an escape route.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

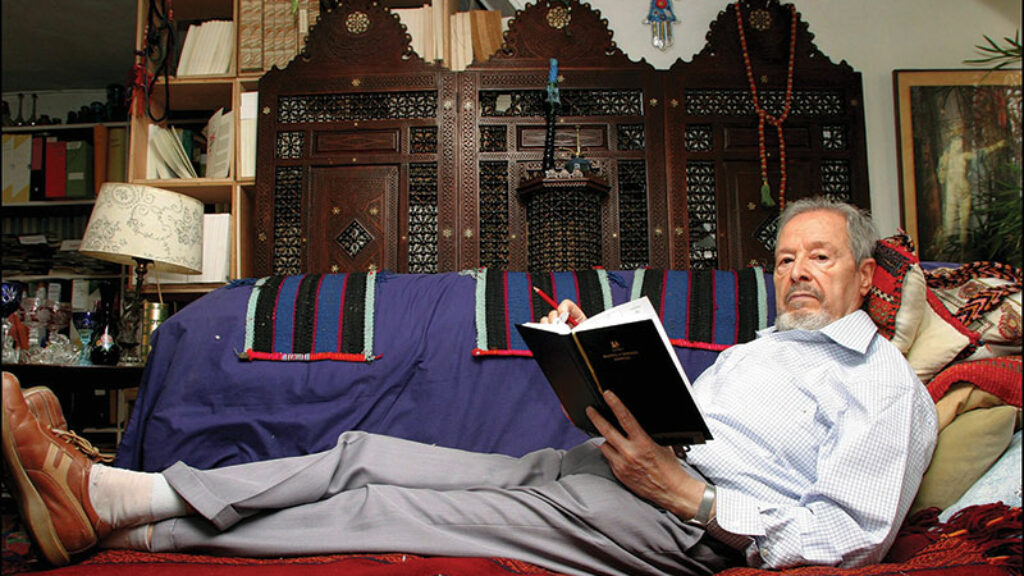

Telling the Whole Truth: Albert Memmi

Albert Memmi began his career as a writer of fiction, but, with the appearance of The Colonizer and the Colonized in 1957, the novelist who wrote like a sociologist became a sociologist who wrote like a novelist.

Sincere Irony

In a new book about religious moderation, William Egginton makes some good points, along with a few immoderate claims.

Talmuds and Dragons

Like the medieval literature to which it pays homage, The Inquisitor’s Tale weaves in supernatural events and divine interventions, mythic beasts and wild peoples, and even entrées into medieval theology, all liberally peppered with puns and potty humor.

Was Exodus a Trick?

“Let us deal shrewdly with them," the Bible quotes Pharaoh as saying. On the deceits of the Exodus story.

gershonhepner

BALFOUR DECLARATION

One nation solemnly once promised land

to a nation called Jews, whom we’ll now call the second,

ignoring the fact that it would soon understand

that a third nation claimed it, would quite soon be reckoned

by Jews a betrayer of its Declaration

which Balfour had signed, and by Arabs regarded

as enemies of the great Arab nation,

whom Balfour’s agenda completely discarded.

Yet Jews who’re Zionists should all be grateful

that Britain was first to get Zion’s ball rolling,

while Arabs who feel Israelis hateful

should listen to bells that for them long are tolling.

What Balfour promised came to to pass. Though granted

some promises were broken, Britain paved the way

for Israel to happen. Don’t be disenchanted.

The goal that Israel scored won’t go away,

providing to all Jews the right that every nation

has to its land. The fact it now exists

is based upon the Abrahamic invitation

God gave their ancestor. The claim persists,

with a history longer than that of all nations

who lack God-given titles to their soil.

I’m sure there would have been far fewer protestations

had God not given Muslims so much oil,

though lots of oil and gas were fortunately found

in Israel, in offshore deposits and

beneath the very soil of this most promised ground,

promising good fortune to the land.

There always have been lots of Jews who are opposed

to what those who love Israel loudly call for,

so that supporter of the state are diagnosed,

as surely was the promise maker Balfour,

as racists and imperialists, a grave defect

that troubles no one more than liberal Jews,

turning Zionists, politically quite incorrect

into Dreyfuses whom they accuse.

gershon hepner

ISRAEL WAS NOT CAUSED BY THE HOLOCAUST, BUT PREVENTS IT

Many people think mistakenly that what caused Israel was the Holocaust;

this connection postulated between them is one that should not be endorsed..

The Holocaust occurred because there was no Israel, as Bibi to the Brits explained

when, celebrating Balfour's Declaration, they about the so-called settlements complained.

Withdrawal to the so-called Green Line would be one to so-called Auschwitz borders,,

and would be more disastrous than the one from Gaza that would give birth to Hamas.

Israel will not take from any of its so-called friends self-genocidal orders,

refusing territorial divestment that's demanded by a Boycott bus.

[email protected]

gershon hepner

ISRAEL WAS NOT CAUSED BY THE HOLOCAUST, BUT PREVENTS IT

Many people think mistakenly that what caused Israel was the Holocaust;

this connection postulated between them is one that should not be endorsed..

The Holocaust occurred because there was no Israel, as Bibi to the Brits explained

when, celebrating Balfour's Declaration, they about the so-called settlements complained.

Withdrawal to the so-called Green Line would be one to so-called Auschwitz borders,,

and would be more disastrous than the one from Gaza that would give birth to Hamas.

Israel will not take from any of its so-called friends self-genocidal orders,

refusing territorial divestment that's demanded by a Boycott bus.

[email protected]