Babel’s Transcendent Mistakes

When I was 12, my parents bought me a gigantic Yiddish-Russian dictionary. Maybe this was their way of compensating for the fact that they had not told me I was Jewish until second grade, when I came home singing a Ukrainian ditty with the word “zhid.” Or maybe the gift was inspired by the Soviet Union’s collapse, which made it possible to purchase such a dictionary in a regular bookstore. That year, I spent many afternoons trying to memorize the words that began with alef. I had a craving for a Jewish language—as identity, as an answer of some sort—and I knew that neither Russian nor Ukrainian would suffice. Needless to say, neither the alef words of Yiddish nor the shreds of Hebrew I picked up in the newly opened Sunday school helped me very much.

That same year, my parents gave me a volume of Isaac Babel’s short stories. The book was handed to me with a gesture that suggested the reverence one reserves for ritual objects—and with a certain glee that seemed to undercut the reverence. And there it was: Babel’s Russian was the first Jewish language I could come to call my own.

Reading, and rereading, Babel particularly his Odessa stories, was an almost hallucinatory experience. The sensory overload of every single image, the dense, drunken music of it all, bewildered me in a way that was visceral. Even today, 25 years later, I still remember how my body felt when I read that book. It was an illicit pleasure—and not merely because of the subject matter—above all, it was the broken Russian grammar and phrasing, wrought with mistakes, that was quite unlike anything else I had ever seen in print. Babel’s characters—Benya Krik, Reb Arye-Leib, Lyubka, Tsudechkis—spoke Russian infused with the hint of another language. It beckoned me: “Forget for a while that you have glasses on your nose, and autumn in your heart.”

Both my grandmother and my aunt taught Russian language and literature in high school. Along with my mother, who grew up in their menacingly pedagogic shadow, they were exacting in their demands on my Russian, which was to be grammatically impeccable and spoken with a properly modulated Slavic diction at all times, whether I was tagging along to the marketplace or reciting poetry. Babel offered an alternative that was revelatory. I may have intuited that the deliberately broken and Yiddishized Russian spoken by Babel’s characters was, like all such creoles or patois, not a sign of backwardness or a symptom of a lack of education. Instead, this was a way one could carve out a self within a culture that seemed to swallow you whole without ever accepting you.

I couldn’t fully understand any of this at the time, of course, but I’ve been thinking about it a great deal lately as I read Val Vinokur’s new translation of Babel’s stories, The Essential Fictions. To translate Babel is to attempt to invent, or reinvent, a language—a Jewish language—particularly given Babel’spredilection for marrying the argot of the underworld with highly sophisticated narration. What would its English equivalent be? Saul Bellow’s high-low American English? Jackie Mason’s tonalities? Mickey Katz’s lyrics? Yeshiva talk? None of these seem quite right, but it is clear that Vinokur is willing to experiment. There is an iconic scene in “The King”: A nameless young man interrupts Dvoira Krik’s wedding celebration. He gets Benya’s attention with a phrase that betrays a Yiddishism lurking behind it, with two twisted conjugations and a well-misused word. There isn’t a trace of this in Peter Constantine’s fine 2002 translation, but Vinokur takes a chance with “I got a couple things to tell you.” The dropped preposition may not create a sense of an invented language, but it hints at something lurking underneath, as does, for example, “Benya, you know what kind of notion I got? I got a notion our chimney’s on fire,” which, too, is smoothed over in Constantine’s work.

Vinokur also pays close attention to names, one of Babel’s specialties: street names, Yiddish names, Slavic names, and especially nicknames. Thus, in Vinokur’s rendition, you get, among others, “Froim the Rook,” “Monya Gunner,” “Lyova Rooski,” and “Ivan Fiverubles.” Vinokur’s impressive work is most challenged, however, in Babel’s complex narration. For instance, describing Benya’s raid he translates, “on that dread night when stuck cows bellowed and calves slipped in their mothers’ blood.” This sounds a bit rough around the edges, especially when compared with Constantine’s elegant “that terrible night when the slashed cows skidded in their mothers’ blood.”

As I read Babel’s Odessa stories in the book my parents gave me, I became more attuned to our older relatives, the ones I saw on our annual pilgrimages to the small village of Haschevato, where my father’s family has its roots. Every year we gathered at the local cemetery, near the mass grave where members of our family who had been too old or reluctant to evacuate during the Holocaust are buried. There, a large wall bears surnames that were very familiar to me, along with first names, of the sort I only encountered in Babel’s work. The elderly relatives I met there, those of my great-grandparents’ generation, spoke Russian much like Babel’s characters did. Listening to them, I understood that the reason my parents had given me this book with such reverence had something to do with these relatives.

Not long after the Soviet Union collapsed and Ukraine became its own country, the government rushed to create a sense of a national literature, slapping together a quick high school curriculum, which I was unfortunate to encounter. We read works of dubious merit—but at least they were written in Ukrainian. A play “One Hundred Thousand,” by Ivan Karpenko-Kary, describes a Ukrainian peasant-dreamer who gets ripped off by an anonymous Jewish counterfeiter. The author had clearly read The Merchant of Venice but lacked Venice, a sense of humor, and an understanding that a Jew had not only eyes etc., but, as Shylock insists, “dimensions.”

He did, however, allow his Jew to speak, occasionally dropping what Karpenko-Kary thought to be Yiddish, or Yiddish-sounding, phrases that elicited much mirth from my classmates as we read the play out loud and recited monologues by heart. To this day, I feel the cold sweat on my neck and the paralyzing shame shooting through me when I think of that play. If I could go back in time and say something to my terrified 13-year-old self, I’d begin with Babel, whose brilliant appropriation of Russian was the real mic drop to Karpenko-Kary and others like him.

The twisted Russian of Babel’s characters is full of sublime mistakes. In one of Benya’s finest monologues, the author reveals to us what they are really all about:

[If] you need my life you may take it, but everyone makes mistakes, even God. A huge mistake has been made, Aunt Pesya. But wasn’t it a mistake on God’s part to settle Jews in Russia and let them be tormented worse than in hell? And would it have been so bad if the Jews lived in Switzerland, where they would be surrounded by first-class lakes, mountain air, and nothing but Frenchmen? Everyone makes mistakes, even God. Listen to me with your ears, Aunt Pesya.

The first Jewish language I learned was the language of mistakes. Mistakes that turned, in defiance, into pure poetry.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

What’s Going On With Antisemitism?

Jonathan Karp responds to Reviel Netz

Facing Faces

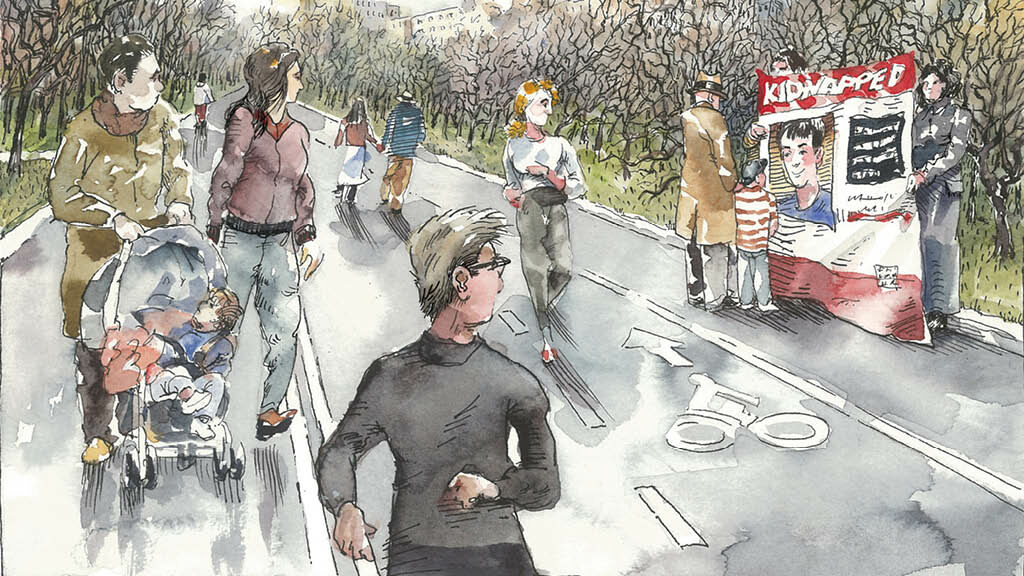

Nearly every morning since October 7, I open my phone and look at the faces of the war’s most recent victims. I gaze at these portraits fearfully, searching for a…

Wandering Jews

Jews have been travelers since God told Abraham to get up and go. How deeply has this constant motion been imprinted on the Jewish psyche?

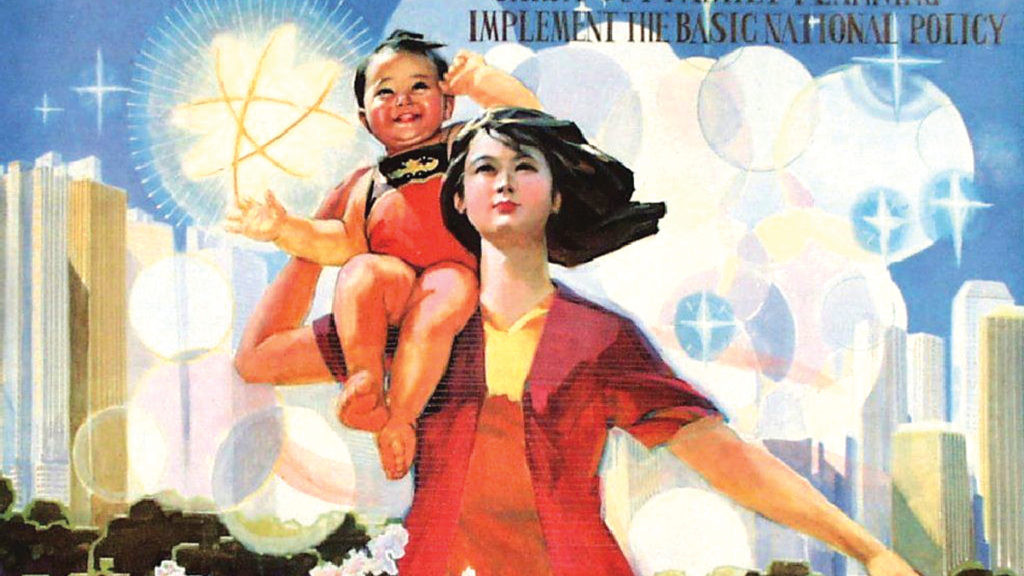

On Not Bringing Up Baby

What happens when the rising cost of raising children meets the downward pressure on reproduction?

judydarsky

Helps me understand what it was like to be Jewish in Russia. Thank you, Jake Marmer.

gershon hepner

LIKE PATIENTS ETHERIZED UPON A TABLE, ISAAC BABEL AND T. S. ELIOT

“Morning came oozing down on us like chloroform oozing down on a hospital table,” Isaac Babel,

a Jew’s description of his experiences with Cossacks while they fought the Jews,

foreshadows T. S. Eliot’s far more famous, “like a patient etherized upon a table,”

though, “That is not what I meant, at all,” might well have been his counter-ooze.

Isaac Babel was unable to grow old, executed when just forty-five;

T. S. Eliot was more successful, almost reaching seventy-seven.

Though he quite infamously reviled in nasty verses all the Jews with whom failed to jive,

I can’t believe his longer life was due to his belief in heaven,

which Isaac Babel surely didn’t, though for many years he did believe that one on earth

would be created by the Bolsheviks, like so many Jews

deluded by utopian fantasies to which lots of them, like Babel, failed to bring to birth,

and with the failure paid the price---their lives. What else is news?

[email protected]