Strange Miracle

“It was the faith of the Jewish people that gathered the scattered fragments of a people and made them whole again; that took the language of the Bible and the landscape of the Psalms and made them live again.” As the Jerusalem Post noted, U.S. Vice President Mike Pence took this and similar statements out of the books of Rabbi Jonathan Sacks and inserted them (in collaboration with Rabbi Sacks) into his impressive speech to the Knesset in January. If Pence had given this address a bit sooner, some of his own words would almost certainly have made their way into Samuel Goldman’s new book, for the evangelical Christian vice president’s affirmation of the Jews’ return to the Land of Israel perfectly illustrates the phenomenon Goldman describes and underscores its continuing importance.

God’s Country: Christian Zionism in America draws on several earlier studies to assist “readers who want to learn more about Christian Zionism but have little background in theology, history, or political theory—let alone all of these fields.” Yet, as a political scientist, Goldman has a broader theoretical point to make as well: to provide an example of the contemporary persistence of political theology—“a way of thinking about the order and purpose of politics oriented by God’s will.”

Jerusalem, January 23, 2018. (Photo by Alex Kolomoisky/POOL.)

The political theology in question is almost entirely Protestant. By the time of Augustine in the 4th century, the New Testament texts that would later serve as foundations for Christian Zionism had been relegated to “the margins of Christian thought.” Only a few pages into his narrative, Goldman is already at Luther, though it was not Luther himself, or even Calvin, but Puritans inspired by the latter who first took Paul’s assertion that in the end “all Israel shall be saved” to imply not just the Jews’ ultimate recognition of Christ as the Messiah but their restoration to the Land of Israel. As eager as these Puritans were to identify the New England in which many of them were settling in the 17th century as a promised land, they never mistook it for the Promised Land. Indeed, Massachusetts clergyman John Cotton predicted that “a willing people among the gentiles” would “convey the Jewes into their owne Countrie, with Charets, and horses, and Dromedaries.”

Neither Cotton nor any of his colleagues envisioned their own neighbors playing this role, but some of their spiritual descendants were ready to shoulder the responsibility. John Austin, a Yale-educated Presbyterian minister in New Jersey, moved in 1797 back “to New Haven, where he began preparations for the restoration of the Jews, buying ships and warehouses to convey them and their goods to Palestine.” Austin seems to have been a bit deranged, but, as Goldman puts it, he nevertheless “made an impression on more balanced minds,” including that of Elias Boudinot, a one-time president of the Continental Congress, a member of the first two U.S. Congresses, and the first president of the American Society for Meliorating the Condition of the Jews. The conversion of the Jews to Christianity was, in his eyes, essential, but his organization’s “goal was also to help the people of Israel return physically to God’s country.”

The series of American Christian proto-Zionists who took their bearings from the letters of Paul, the biblical prophets, and the apocalyptic writings included, among others, a 19th-century NYU Bible professor and abolitionist by the name of George Bush, an ancestor of the two similarly named presidents. Bush believed that Christians should not be “waiting for a miracle” but “should concentrate on creating the political conditions for a Jewish return to the land” (after which, of course, their conversion would eventually follow).

It is not until the middle of his book that Goldman discusses the theologians widely and, as he shows, mistakenly believed to be the original forbears of Christian Zionism, the “premillennial dispensationalists.” The foremost among them, the British clergyman John Nelson Darby (1800–1882), taught that the last seven years before Christ’s return would witness “the territorial restoration of Israel, the establishment of a covenant between Israel and the Antichrist, the Antichrist’s betrayal of that agreement and ensuing persecution of Israel, and finally the rescue of a pious remnant by the visibly returned Christ.” While Darby himself kept his distance from Jews and had no interest in politics, some of his successors in this country fused dispensationalism with “more positive conceptions of American destiny” that involved responsibility for the status of the Jewish people. This brought them into contact with early American Zionists.

Of these, the most noteworthy was the dispensationalist theologian William Eugene Blackstone, who is best remembered for initiating the Blackstone Memorial, a petition that called upon President Benjamin Harrison to do for the Jews what Cyrus had performed for them in antiquity a full six years before the First Zionist Congress. As Goldman notes, however, the petition “includes no explicitly dispensationalist arguments” and is based mainly on “humanitarian considerations.” Later, in the middle of World War I, Blackstone was encouraged by American Zionist leaders to revise the proposal for President Woodrow Wilson. It was endorsed by 81 prominent figures and a variety of church organizations. “The ecumenical character of the signatories,” Goldman tells us, “reflects the fact that Christian Zionism was not then associated with apocalyptic expectations or conservative politics.” Included among them were “theological and political liberals such as the Methodist bishop J. W. Bashford; F. M. North, president of the Federal Council of Churches of Christ; and YMCA leader John R. Mott.”

Goldman’s account of Christian Zionism between the Balfour Declaration and the establishment of the State of Israel highlights the extent to which Zionism won the support of theological liberals as well as conservatives, though he does not ignore the liberals who were critical of it. On the one hand, there was Adolf A. Berle, a professor of applied Christianity at Tufts University (and the father of A. A. Berle Jr., the FDR adviser), for whom Zionism seemed to herald “the new Messianic Kingdom,” as well as an opportunity for the renovation of Judaism. On the other hand, there were clergymen like Harry Emerson Fosdick and John Haynes Holmes who believed that the Zionist project would lead to the usurpation of Arab rights unless it eschewed the idea of Jewish statehood.

The liberal Protestant figure to whom Goldman devotes the most attention is, of course, the great theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. Although Niebuhr “did not appeal to biblical prophecy in the same way as Blackstone,” his pro-Zionist argument was “based on his theological commitments and aimed to weave contemporary events into the continuing story of God’s covenant with Israel. Niebuhr was a Christian Zionist, not just a Christian who supported Zionism.”

Niebuhr was not oblivious to the problems that had disturbed Fosdick and Holmes. He granted that the creation of a Jewish state would entail some measure of injustice to the Arabs of Palestine, but he argued that it “would be less serious than the consequences of denying a state to the Jews.” The Jews needed a country of their own in order to survive as a nation, whereas the Palestinian Arabs, who “understood themselves as generic Arabs rather than a distinct people attached to a particular place,” could exercise their national rights effectively enough in neighboring lands. Afflicted also by a “sense of shame” with respect to the Christian past, Niebuhr argued already in 1938 that the establishment of a Jewish state could serve as “‘a partial expiation’ for the vexed history of Jewish-Christian relations.”

After the creation of the State of Israel, Niebuhr consistently defended it against both theological and political critics. In early 1957, he denounced the Eisenhower administration’s harsh policy toward Israel after the Suez War. Writing in the New Republic, he spoke of Israel not only as a small and beleaguered nation but as a “‘glorious spiritual and political achievement’ that embodied Western civilization.” Later, he emphasized, as Goldman puts it, that the United States and Israel “were yoked together in a providential task.”

Despite all the risks of combining politics with religion, “there is the strange miracle of the Jewish people, outliving the hazards of the diaspora for two millennia and finally offering their unique and valuable contributions to the common Western civilization, particularly in the final stage of its liberal society.” In order to fulfill its role as defender of Western civilization, America was called to defend the “peculiar historical miracle” in the Middle East.

This is a far cry from “the politically conservative, prophetically inflected version of Christian Zionism” that is most in evidence today and to which Goldman devotes the last chapter of his book. His survey of recent Christian Zionist figures, such as Hal Lindsey, Jerry Falwell, and John Hagee, shows how thoroughly they have absorbed and adapted the eschatology of the previous century’s premillennial dispensationalism. But as remote as they may be from Niebuhr’s sober Weltanschauung and his liberalism, they arrive at a bottom line parallel to the one he drew. They believe, in Goldman’s words, that American Christians

should not hope to take Israel’s place in God’s affection. But they could bask in the reflected glory of Israel by acknowledging its chosenness. God Himself promised to bless those who blessed the Jews. So long as it supported Israel, America would enjoy more divine favor than it actually deserved. The catch was that America’s relationship to God was conditional, unlike Israel’s irrevocable covenant. If it became derelict in its duty, God would withdraw His support.

Interestingly, Goldman argues that in the case of Hagee and several others, this position was also partly motivated by their historical awareness of the Holocaust.

Goldman’s review of the history of American Christian Zionism demonstrates striking continuity from the Puritan era to the present, with theologians of very different orientations reaffirming, century after century, the need for America to exert itself in support of the Jewish people. But what does Goldman himself think of them, the dispensationalists in particular? Clearly, he does not share their penchant for looking to the Bible for political guidance. He is, after all, only “a minimally observant Jew,” and a rationalist who understands that premillennial dispensationalism is “flamboyantly irrational to secular eyes” and that this only “encourages the sensationalist treatment it often receives,” not least in the liberal Jewish press.

After noting this, Goldman makes an interesting point. He writes that the determinism of the dispensationalists’ political theology “shares an important quality with an avowedly atheist doctrine that emerged around the same time. Like Marx’s philosophy of history, premillennial dispensationalism establishes a logic of transformation through catastrophe and suggests that the final stage is about to commence.” But Goldman is not making this observation in order to rehabilitate the dispensationalists in the eyes of secular skeptics; he wishes only to show that their theology places them in a dilemma somewhat similar to the one faced by Marxists: In a world where all is determined, may one just wait for things to unfold as they necessarily will, or is there still a need to act?

For decades now, American Jews have reacted to dispensationalist supporters of Israel by holding debates about whether their help is worth having. Goldman, an admirer of the modern State of Israel, apparently has no doubts about this, but he does see the downside. If Christian Zionists’ support for Israel is rooted in “unsettling eschatological visions,” it is easy to see them “as a radical and potentially subversive influence on the United States, Israel, the Middle East, and the world.” One of Goldman’s aims, therefore, is to dispel the idea of any necessary connection between Christian Zionism and outlandish prognostications about the end times. Nonetheless, it remains the case that few of today’s Christian Zionists are the heirs of Reinhold Niebuhr. As Goldman himself notes, after Israel’s victory in the Six-Day War, mainline Protestant “intellectuals and clergy drifted away from Israel, which they increasingly regarded as an outpost of imperialism, colonialism, and other sins.”

If contemporary Christian Zionists, however, are often inspired by strange apocalyptic imaginings, this has not moved American policy in irrational ways. As Goldman shows, no one has ever “demonstrated that these strategies diverted U.S. foreign policy far from its recent course.” What they have done is helped to get out the vote for pro-Israel candidates. It is also important to note that “themes of covenant have become more prominent than prophecy in Christian Zionist appeals.”

What is disturbing to supporters of Israel is that Christian Zionism may be losing support among young evangelicals. Goldman cites Christian Middle East activist Robert Nicholson’s claim that “more and more American evangelicals are being educated to accept the pro-Palestinian narrative—on the basis of their Christian faith.” Goldman himself takes this in stride. It would be premature, he says, to write Christian Zionism’s obituary. It may be waning in the United States, but it seems to be growing elsewhere, in Brazil, for instance. But how many of the people who are alarmed by the trend Nicholson describes, and its political implications, are likely to be consoled by this news?

Suggested Reading

When Canines Were in the Land

Did dogs save the Jewish State?

The Rogochover Speaks His Mind

After he visited the odd talmudic genius, Bialik said that “two Einsteins can be carved out of one Rogochover.”

Pro-Creation

Economist Bryan Caplan thinks parents “overcharge” themselves when it comes to investing in their children. Glückel of Hameln knew better.

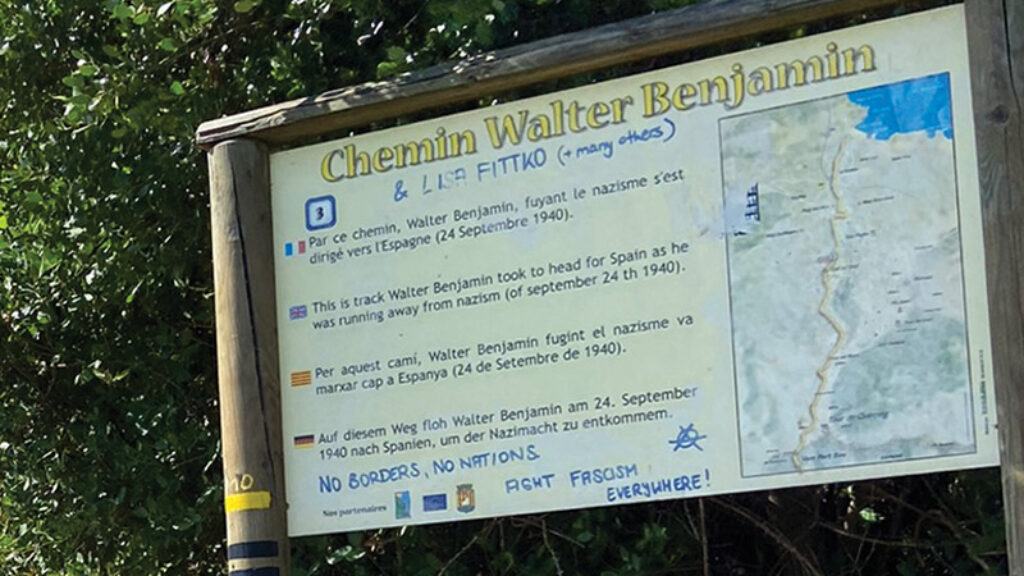

Walking with Walter Benjamin

On losing one’s self in Walter Benjamin’s final wanderings.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In