Maimonides in Ma’ale Adumim

In 1977, I received a slender volume of commentary on Moses Maimonides’s codification of Hilkhot Teshuvah (Laws of Repentance) in his Mishneh Torah. It was by a former teacher of mine, Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch, who was then the principal of Jews’ College in London, and it was called Yad Peshutah. The title, which means “Outstretched Hand,” is a clever play on the alternative name sometimes used for Maimonides’s 14-volume code of Jewish law, Yad ha-Hazakah, or “Strong Hand” (the two Hebrew letters composing the word “yad,” or hand, also stand for the number 14). Thus, the title implied, Rabinovitch’s commentary was an attempt to reach back across the generations to Maimonides in the 12th century and out to contemporary students of the code—and that it aimed to do so by elucidating the peshat, or most straight-forward meaning, of the text.

In its preface, Rabinovitch announced his audacious plan to extend this approach to the entire Mishneh Torah. What struck me most then—and strikes me all the more powerfully these 40 years later, as that initial 148-page volume has blossomed into the most systematic, comprehensive commentary on Maimonides’s code ever produced—was not the work’s ambition. Rather, it was its systematic clarity and methodological precision, combined with the author’s extraordinary mastery of all of Maimonides’s works, from the book on logic he wrote as a young man to his final masterpiece, The Guide of the Perplexed. Rabinovitch’s guiding principle, which he repeats several times, is that “Maimonides must be interpreted through Maimonides.” The 23 massive volumes of the now almost complete Yad Peshutah bear out the fruitfulness of this approach. As Rabinovitch shows, Maimonides was a remarkably consistent thinker whose halakhic positions in the Mishneh Torah were meticulously coordinated with his philosophical reasoning.

Although Rabinovitch is, in many respects, a traditional rosh yeshiva—his prose integrates elements of “yeshivish” Hebrew with a mélange of classical and modern styles—he is surely the most thoroughly Maimonidean thinker of our age, not only in this massive commentary, but also in his consummately rationalist works on Jewish law, theology, and Zionism. He is, to put the point piously, perhaps the most impressive and the least well known of our sages.

Born in Sainte-Sophie, Quebec, a farming town at the foothills of the Laurentian Mountains north of Montreal, in 1928, Rabinovitch was sent as a teenager to study at that city’s only yeshiva, Merkaz Hatorah, where he was discovered by Montreal’s then chief rabbi, the late Pinchas Hirschprung, who ordained him at the age of 20. From Montreal, Rabinovitch went on to study with Rabbi Yaakov Yitzchok Ruderman at Baltimore’s Ner Yisrael yeshiva, from which he received a second ordination, while at the same time completing an advanced degree in mathematics at Johns Hopkins University. In his first rabbinical post, Rabinovitch was the leader of the small Orthodox community in Charleston, South Carolina, where he established its first Hebrew day school. In 1963, he returned to Canada to lead the Clanton Park Synagogue in Toronto. While there, he completed a doctorate in the history of science at the University of Toronto. In 1971, he accepted the stunning offer to become principal of Jews’ College in London. Ten years later, in a move that shocked his colleagues and students, he accepted another unlikely offer, to become the rosh yeshiva of Birkat Moshe, a small yeshiva in Ma’ale Adumim, a settlement a few miles outside of Jerusalem, on the other side of the Green Line. At the time, Birkat Moshe was little more than a trailer with a few students, but it had been founded by two brilliant young scholars: Chaim Sabato, who would go on to become a prize-winning novelist, and Yitzhak Sheilat, who would later edit and translate the most meticulous and widely consulted edition of Maimonides’s letters. Over the last four decades, Birkat Moshe has become one of the leading Zionist yeshivot in Israel, with an important press.

His extraordinary career and accomplishments notwithstanding, Rabbi Rabinovitch is hardly known to diaspora Jews, even those steeped in the rabbinic tradition. His approach is simply too modern, halakhically lenient, and philosophically sophisticated for most of the Orthodox world, let alone the haredi one. Moreover, his regular references to the all-but-banned Guide of the Perplexed certainly place him beyond most pales of Orthodox settlement—I know of no other rosh yeshiva who regularly lectures on the Guide. Nor, despite perennial academic interest in Maimonides, is Rabinovitch particularly well known among university-based scholars of Jewish studies.

As a rabbi, he cedes his judgment and authority to no religious organization, political party, or venerated Orthodox rabbinical tribunal, regardless of how many “Torah giants” fill its mass meetings’ massive daises. He also has shown a brave indifference to the single most powerful religious institution in the Jewish State, Israel’s Chief Rabbinate. Three years ago, together with Rabbis Shlomo Riskin and David Stav, Rabinovitch established an independent beit din to handle the cases of the thousands of Israeli candidates for conversion to Judaism with greater compassion, efficiency, and leniency than had been shown by state-sanctioned rabbinic courts.

As it happens, when I received that first volume of Rabinovitch’s Yad Peshutah, I was in graduate school, studying under the foremost academic scholar of Maimonides’s legal code, Harvard’s Isadore Twersky. Ten years earlier, Twersky had published an article called “Some Non-Halachic Aspects of the Mishneh-Torah,” in which he argued, against a scholarly consensus stretching back to the 19th century, that Mamonides’s philosophical and legal writings were not only compatible but complementary. The Mishneh Torah was not simply the public, communal work of a radical philosopher, whose Guide of the Perplexed secretly undermined many of its religious certainties, as many scholars (most famously Leo Strauss and Shlomo Pines) had argued. Rather, Maimonides was a philosopher-theologian who (more or less) consistently taught the same rational religion, though he wrote differently for different audiences. In 1977, Twersky was in the midst of finishing his masterpiece, Introduction to the Code of Maimonides, which argued for this reading in extensive detail. Thus, two great scholars, working independently of one another, crafted a formidable set of arguments for the unity of Maimonides’s work, one in a 600-page hibbur, the other in a 12,000-page (!) perush (to borrow the master’s own terminology in distinguishing his works of codification from those of commentary).

In choosing to write a commentary rather than a book, Rabinovitch boldly inscribed himself in an almost 800-year tradition, from the cryptic animadversions of Maimonides’s contemporary Rabbi Abraham ben David of Posquières (known as Rabad) through the early 20th-century classic Ohr Sameach by Rabbi Meir Simcha ha-Kohen of Dvinsk. And yet, while Yad Peshutah is largely exegetical, working line by line through the text of the Mishneh Torah, it also contains many brilliant self-contained essays. The first is Rabinovitch’s essay on Maimonides’s own introduction to his code, an immensely important history of halakhic jurisprudence. In this introduction, Maimonides lists the Torah’s 613 commandments, as he had done more expansively in his earlier Sefer ha-Mitzvot (Book of the Commandments). These lists correspond, but not perfectly, as has long been obvious to historians of halakha. Rabinovitch reconciles them and then goes on to coordinate them with the classification of the commandments in the third part of the Guide, where Maimonides introduces his famous Ta’amei ha-Mitzvot (Reasons for the Commandments). Here, Rabinovitch does what others had only gestured at; he carefully works through all 613 mitzvot demonstrating that there are no contradictions between Maimonides’s three accounts.

Nonetheless, given the long and rich literary history of Maimonidean scholarship one may wonder what could possibly be added to such an embarrassment of exegetical riches on a line-by-line basis. Based on a more than two-year-long reading of Yad Peshutah, my answer is to pose another question (bordering on a kvetch), “Oy, where even to begin?” Well, probably with Rabinovitch’s establishment of the most accurate possible version of the text of the Mishneh Torah, based on decades of assiduous research on manuscripts from Cambridge and Oxford to Jerusalem and Cairo. Having established to his satisfaction the ideal text, Rabinovitch explains the logic or rationale behind Maimonides’s ordering of each halakha (or roughly speaking, in this context, paragraph) in the code’s 14 books; second, he compares each ruling to every analogous discussion in Maimonides’s earlier halakhic works; third, he turns to explicate the text itself, while cross-referencing and harmonizing it with all related sections elsewhere within the Mishneh Torah; finally, he does much the same with regard to all of Maimonides’s other writings, including his responsa, epistles, philosophical and even medical works.

Over the years, Rabinovitch has tended to add more and more of his conversations with the traditional rabbinical commentators who surround the text in the classical editions of the Mishneh Torah, including the Mishnah la-Melekh, the Kesef Mishnah, the Hagahot Maimoniyot, and many others. Revealingly, Rabinovitch never once mentions the Lithuanian yeshiva world’s most cherished glosses to the Mishneh Torah, namely the celebrated Hiddushei Rabenu Haim Halevi, by the legendary “Brisker Gaon,” Rabbi Chaim Soloveitchik. The conceptually innovative, but famously forced, Brisker methodology could hardly be farther from Yad Peshutah’s goal of clarifying the plain meaning—the peshat—of Maimonides’s text.

Indeed, Rabinovitch is scarcely less bold than Maimonides himself in challenging his great rabbinic predecessors. Thus, when he disagrees with Maimonides’s formidable 13th-century mystical critic Nachmanides, known by his Hebrew acronym Ramban (just as Maimonides is known as Rambam), he will typically write, “Although I am but dust under the feet of the great Ramban . . .”—and then proceed to demolish his argument. In such places, one feels the calm intellectual confidence exuded by Rabinovitch, which may be the natural result of being modestly aware—but aware nonetheless—that he has mastered an entire tradition. (It also must be said that this partisanship clearly differentiates his approach from that of his academic contemporaries.)

Of the many hundreds of passages that might be analyzed to illustrate precisely how Yad Peshutah “works” let us turn to the first two chapters of Rabinovitch’s commentary to Maimonides’s Hilkhot Mamrim (Laws Concerning Rebels). This new legal category is a particularly strong example of Maimonides’s daringly original reclassification of halakha. There was simply no precedent for the existence of a distinct category of laws about “rebels.” The term “mamrim” is of biblical origin: “You [the generation of the desert] were rebels against the Lord your God” (Deut. 9:24), but its use as a rubric to bring together nine biblical commandments whose talmudic elaborations are scattered across some 11 tractates is Maimonides’s invention. Arguably its most original feature is placing laws pertaining to the judicial authority of the ancient Sanhedrin in Jerusalem together with the laws of filial responsibility, from the obligation to honor one’s parents to the draconian punishment of “the deviant and rebellious son.”

Maimonides never stated his reasons for reclassifying the entire corpus of Jewish law as it had been ordered since mishnaic times, and neither did his commentators, at least not in any systematic, comprehensive way. In his preface to Hilkhot Mamrim, Rabinovitch cites several selections from The Guide of the Perplexed where Maimonides explicates the laws of the judiciary and appends the capital offense of the “rebellious son” to the prohibition of rebelling against rulings of the High Court. Then, Rabinovitch succinctly explicates the political reasoning of the Guide:

Clearly, however, before introducing the case of the rebellious son, which is the most extreme example of the destruction of family structure, one must first also explicate the obligations and imperatives to honor and fear parents, for only thus will the home [and the nation] be built upon the most durable foundations.

In this preface, Rabinovitch also handily and characteristically defends Maimonides against his great critic Nachmanides. Nachmanides wonders how Maimonides can classify the violation of the Rabbis’ interpretations and decrees as a violation of a biblical commandment. Rabinovitch retorts by noting that Maimonides has already implicitly answered this question in his precise framing of these laws:

The High Court in Jerusalem is the foundation of the Oral Torah, and they are the pillars of instruction from whom laws and statutes go out to all of Israel. Concerning them, the Torah promises “You shall do according to the laws which they shall instruct you. . . .” (Deuteronomy 17:11) This is a positive commandment.

Consequently, we are biblically commanded to obey rabbinic rulings.

Having established the biblical basis for the authority of rabbinic courts, in the second chapter of Mamrim Maimonides provides an expository list of what we might call chinks in the Sanhedrin’s armor. Here, Rabinovitch plunges into a deeply learned discussion of the general issue of legal precedent. Indeed, these 25 dense pages could be published as a separate monograph, perhaps called On Stare Decisis in Rabbinical Law. Although Rabinovitch rarely cites the work of modern scholars, in these pages he shows his mastery not only of traditional 19th– and 20th-century commentary on Maimonides but also of academic work on Maimonides, including that of Shlomo Zalman Havlin and Gerald (Yaakov) Blidstein. Such a mixed array of citations is simply not to be found in any earlier commentary to Maimonides’s code.

As I read Rabinovitch, he systematically highlights the cases in which later courts may legitimately overturn the decisions of their predecessors, even by “resurrecting” long-ago rejected minority court—or even individual—opinions. On every occasion that presents itself, Rabinovitch extends Maimonides’s concessions to later courts and opinions to their logical end (and, arguably, even beyond it). This tendency to limit the authority of precedent is at one with his overall, scientifically oriented philosophy of Judaism, which is deeply rooted in the idea of historical progress.

A detailed analysis of Rabinovitch’s doctrine of precedent would be impossible in the present context. Instead, I will conclude with a more familiar subject: the prohibition of cooking, or eating, meat and milk together. The source of the prohibition as we know it lies in the rabbinic interpretations of each of the three appearances in the Torah of the verse “You shall not boil a kid in its mother’s milk.” (Ex. 23:19, Ex. 34:26, Deut. 14:21) All of these expansions of that literal prohibition are considered to carry the weight of biblical law—with one very notable exception, namely the inclusion of chicken (and other fowl) in the category of “meat.” This goes back to a ruling of the 2nd-century sage Rabbi Akiva, but, as Rabbi Yossi the Galilean remarked, birds don’t produce milk. Consequently, Rabbi Akiva should be understood as “building a fence around the Torah”—to prevent a slide down the slippery slope from chicken parmesan to a cheeseburger, and so on.

What does this have to do with the laws dealt with in Chapter Two of Mamrim? After dealing with the scope of rabbinic authority, Maimonides applies the prohibition of neither adding nor subtracting from the Torah to the Sanhedrin and all subsequent rabbis. In particular, they may not present a purely rabbinic law as having biblical authority. After Rabinovitch establishes the precise text of these passages (he relies on the variant manuscript of Maimonides’s descendent Rabbi Yehoshua ha-Naggid), he notes a strange consequence of Maimonides’s ruling: A court or rabbi who claims that the prohibition against eating chicken and dairy together is biblical violates the biblical prohibition of adding to the laws of the Torah. (One imagines a wayward student enjoying a chicken parmesan sub when his rabbi appears and rebukes him for violating the famous commandment not to “boil a kid in its mother’s milk,” thus committing a biblical felony, whereas his student would be guilty of only a rabbinic misdemeanor—the irony would be more delicious than the sandwich.)

To the extent that Rabinovitch has a public reputation, it is as a liberal on the one hand and a hardline ultrarightist on the other. The first reputation is due to his principled break with Israel’s Chief Rabbinate on their intolerant approach to conversion. By contrast, based on a few rather shocking political statements, Rabinovitch has become erroneously labeled as a messianic Zionist extremist. Although Rabinovitch is on the political right in Israel, this is a terrible distortion.

In fact, one of the most striking aspects of Rabinovitch’s philosophy of Judaism is its universalist humanism. He has, it must be acknowledged, said some incendiary things. In a private, secretly taped conversation, he reacted to the Israeli government’s 2005 decision to forcibly evict the Jews living in Gaza by suggesting that they should booby-trap their homes with explosives and warn the evicting soldiers that they were doing so. This, to put it mildly, was not such a good idea. More recently, he inexcusably compared members of the Knesset to members of the notorious Judenrat councils in the Nazi ghettos. Such extreme remarks are the result of his passionate but thoroughly unmessianic conviction that territorial compromise is a mortal danger to Israel and its citizens. Rabinovitch, who is by nature a lenient halakhist, tolerates no compromise, seeing it in the context of the obligation to save human lives (pikuach nefesh). In short, on this one issue, his passionate humanism buttresses his extremism.

At the same time, Rabinovitch’s profound concern for the sanctity of human life has led him to take what might be termed “liberal” views that are not shared by the large majority of Religious Zionist rabbis. For example, in a highly unusual, if gentle, rebuke of the famed Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik, Rabinovitch firmly rejected the notion that all mortal enemies of the Jewish nation throughout its history are to be classified as Amalekites, condemning this as a dangerous idea with no basis whatsoever in halakha. Throughout his work, including a 2006 volume of responsa to queries from IDF soldiers, Rabinovitch insists on treating Gentiles, all Gentiles, regardless of their religion (barring ancient idolatry) or the degree of their hatred of Jews and Israel, as fellow human beings with all the rights that implies. In this regard, he is fond of quoting a verse from Psalms 145:9: “God’s mercy extends to all His creations.” This view also leads Rabinovitch to rule that it is incumbent on medics in the IDF and Israeli doctors, as well as any bystanders who can assist, to treat and save the lives of Arab combatants, even those of terrorists wounded in the course of attacking Israelis (and even on the Sabbath).

This same universalist liberalism is evident in Rabinovitch’s general assessment of both Christianity and Islam as movements that spread the originally Judaic principles of monotheism, morality, and even messianic hope to the entire world. He has praised the Catholic Church’s Second Vatican Council, even citing the text of Nostra Aetate as correcting what he regards as the historical perversions of Paul’s true attitude toward the Jews, which was in the end one of love.

Rabinovitch actually rejects the messianic ideology of many of his fellow Religious Zionists, which he decries as halakhically unfounded and dangerously close to racism. This is consistent with his general—and classically Maimonidean—derision of all mystical and actively messianic theologies of

Judaism. Relatedly, he has condemned the arrogance of those who attempt to explain the Holocaust, in particular those of his fellow Zionists who see the Shoah as the necessary precursor to the gevurah embodied in the heroic rise of the modern Jewish State. Indeed, Rabinovitch advises deleting the phrase “reishit tzmichat ge’ulateinu” (the first flowering of our redemption) from the standard Prayer for the Welfare of Israel, chanted every Shabbat morning in most synagogues. Rather, he cautiously compares the still relatively young Jewish State to the early years of the Second Jewish Commonwealth, asking, “would the [initial] victory of the Maccabees have justified dubbing the Hasmonean Empire as the ‘beginning of the final redemption’?”

I have left the most damning allegation against Rabbi Rabinovitch for last, because it is unfounded. Shortly after the assassination of Prime Minister Rabin in 1995, it was widely reported that Rabinovitch was among those who had applied the “laws of the rodef” (a lethal pursuer whom one is permitted to kill in self-defense) to Rabin, thus helping to create the poisonous ideological climate that made his murder possible. But the crazed assassin Yigal Amir never set foot in Rabinovitch’s yeshiva, and when Rabinovitch was publicly asked whether he regarded Rabin as a rodef, his consistent and curt response was a passionate “chas ve-shalom” (roughly, heaven forbid). Neither the governmental Shamgar report on Rabin’s assassination nor journalist Dan Ephron’s excellent book Killing a King so much as mention Rabinovitch, and yet the calumny—“fake news” if anything is—persists.

While Yad Peshutah will almost certainly end up being studied mainly by scholars, Rabinovitch’s works as a practicing halakhist have always aimed to make traditional life as livable as possible for his fellow Jews. Although the range of the topics he has covered is encyclopedic, a consideration of a handful of his teshuvot (responsa) will round out his portrait. In these decisions, he has consistently discouraged the trend among religious Jews to add customs and stringencies that their parents and ancestors did not observe, which he generally regards as pious showboating (a phenomenon, he notes, that the Talmud called “yuhara”). And he is brutally dismissive of rabbinic peers who inevitably lean toward stringency, citing an epigram that a rabbi who is always blindly stringent will in the end merit followers who blindly violate the Torah. In another responsum (this one about family law) he expresses similar exasperation, condemning those rabbis who, relying solely and without any historical perspective on precedents, rule stringently, when a recognition of recent scientific progress would require far more leniency. And then there is one responsum where Rabinovitch flies into a true rage. When some of Toronto’s Orthodox rabbis restricted access to the formerly ecumenical community mikvah that he had been central in establishing, he sarcastically described them as “little foxes desecrating the vineyard of the Lord” (a play on Song of Songs 2:15).

Throughout his impressive body of halakhic decisions, Rabinovitch consistently applies Maimonidean philosophical and historicist principles. His responsa on matters of women’s modesty, for instance, all conclude with an almost identical formulation: No single standard applies to each and every woman in all times and places, so each must base her decision in these deeply personal matters on the standards and norms of the particular community in which she lives. Similarly, in allowing men in shorts and T-shirts to don tefillin and lead public prayers, Rabinovitch recognizes the modern Zionist reality of Orthodox Jews toiling in the Israeli heat on kibbutzim and moshavim and in cities, again always insisting that the norms of each community determine such matters.

Throughout his long, distinguished career Rabinovitch has stood firmly against the legal application of the romantic doctrine of the “decline of the generations” (yeridat ha-dorot), which insists that with each new generation, knowledge is diminished as we grow ever distant from the revelation at Sinai. He is a guardian of tradition who believes in progress—in short, a Maimonidean. In the year of his 90th birthday, and a little more than 40 years since he began his monumental Yad Peshutah, Rabbi Rabinovitch is perhaps unique in meriting a slight spin on the famous old saying applied to Maimonides: “from Moses to Moses, may there arise more like Nachum.”

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

Maimonides and Medinat Yisrael

Moses Maimonides may have left the Land of Israel for Egypt, but his thoughts on the messianic future are still relevant to the modern Zionist project.

Life on a Hilltop

City on a Hilltop is superbly researched, altogether accessible, and will dispel many lazy stereotypes about the people whose story it tells. But it leaves out a lot.

Thoroughly Modern Maimonides?

Three recent books elucidate what, if anything, Maimonides has to say to us today.

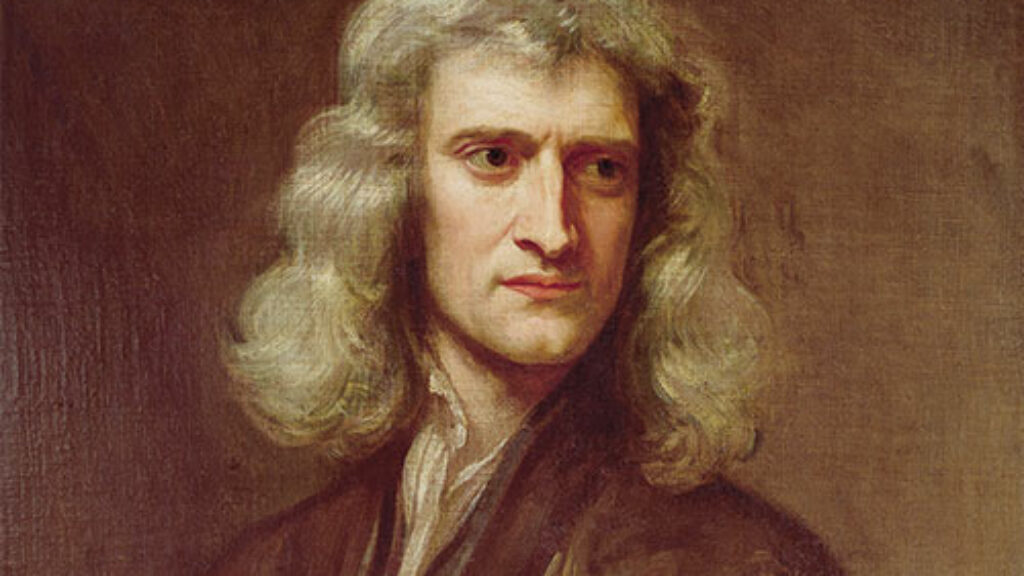

Maimonides, Stonehenge, and Newton’s Obsessions

It takes a bit of a genius to successfully study a genius, and in this case one must first master the millions of words Isaac Newton wrote about natural theology, doctrine, prophecy, and church history.

Bernard Wasserstein

I am astonished and disturbed to read the article you have published by Alan Nadler extolling the ideas and personality of Nachum Rabinovitch whom he presents as a veritable Maimonides redivivus. His encomium of Rabinovitch as an advocate of “universalist humanism” sits awkwardly with his candid admission that Rabinovitch uttered vile incitements to violence (some recorded on tape) on several occasions. Your readers deserve better than such whitewashing of a settler-rabbi who represents much that is most despicable in modern Israeli and Jewish life.

asmith

Allan Nadler Responds:

May I suggest to Dr. Wasserstein, whose own scholarly work I have long admired, that he spend some time actually studying the works of Rabbi Nachum Rabinovitch and learning more about his actual career, halakhic views, and personality before condemning him as representing “much that is most despicable in modern Israeli and Jewish life.” The accusation that my article in any way “whitewashed” Rabinovitch suggests the cover-up of some horrible crime, an accusation based on a secretly recorded personal conversation, rather than a vast body of rational and humanistic rabbinic scholarship, which represents to me that which is so admirable and inspirational in modern Israeli and Jewish life. My piece was an analysis of his masterpiece on Maimonides’s Code of Law, a work of unprecedented magnitude and scholarly fortitude. I had no choice but to address the calumnies against Rabbi Rabinovitch, which have unjustly tainted one of today’s greatest rabbinical minds and distracted attention from what is most important and true about his life and work, calumnies now resurrected carelessly by Dr. Wasserstein.