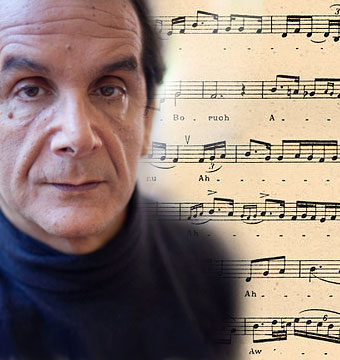

Charles Krauthammer’s Gift to Jewish Music

One hot summer day in 2003 I was strolling through New York’s Central Park when my cell phone rang. It was an old friend calling with a surprising proposal. Did I know the Washington Post columnist Charles Krauthammer? He was seeking scholarly advice for a new Jewish musical project. The timing could not have been worse. I was due to leave in a matter of weeks for a Fulbright year in Ukraine and Russia to do dissertation research on the birth of modern Jewish culture—including Jewish music—in late imperial Russia. Plus, years of speaking at JCCs and synagogues had left me weary of audiences whose idea of Jewish music started with “Hava Nagila” and ended with the theme from Schindler’s List. Why, I wondered, was a renowned political commentator with no musical background pledging his energies to the cause of Jewish music?

A week or so later I found myself sitting in a Dupont Circle office in Washington, D.C., listening with growing fascination as Charles and his wife, Robyn, a painter and sculptor, explained their shared vision of a new nonprofit arts organization to promote the riches of the Jewish musical past. To my surprise, their inspiration derived from a chance encounter with the very same group of obscure early 20th-century Jewish composers—Joseph Achron, Joel Engel, Alexander Krein, and others—that I was about to research in the archives. These musical men and women had labored alongside the likes of Marc Chagall, Sholem Aleichem, and Chaim Nachman Bialik to transform Yiddish folk traditions into modern art: the first Jewish operas, violin concertos, art songs, and the like. I was en route to the newly opened former Soviet archives to recover their forgotten musical legacies. Charles and Robyn had embarked on ambitious plans to launch a semiannual concert series at the Kennedy Center focused on unknown Jewish classical music.

Over the next decade, I served as academic advisor to the resulting Pro Musica Hebraica series as it premiered dozens upon dozens of extraordinary compositions plucked straight from musty archives across the world. Each concert welcomed in world-famous artists such as Evgeny Kissin, Marc-André Hamelin, and Itzhak Perlman alongside up-and-coming talents from North America, Europe, and Israel. They proceeded to perform music that hardly anyone knew existed: baroque Hebrew oratorios from 17th– and 18th-century Holland and Italy; mid-19th-century French Jewish romantic-style piano settings of Hebrew liturgical hymns; klezmer violin fantasias from pre–World War I shtetls that blurred the line between classical virtuosity and folk pathos. The list went on and on. All were introduced from the stage before each concert by Charles in a witty personal monologue that winked at the standard Washington audience obsession with politics while deftly redirecting their attention to the musical matters at hand.

As word grew of the Pro Musica Hebraica concert series, entreaties and proposals began to roll in from across the world. Inevitably, the media also came calling in search of a great story about how one of their own took up this quixotic cultural mission far removed from the day-to-day battles over American politics, Israel, and the Middle East, and even his own stated first love, baseball. Some saw it as an extension of his quiet generosity as a Washington philanthropist, in which capacity he helped to launch a local Jewish day school and other area educational programs. Others imagined it was somehow related to a preemptive defense of Israel. Neither was the case, at least from my perspective. For in our years of conversation about Jewish music, Charles Krauthammer the musical impresario revealed himself to be motivated by a remarkably simple set of convictions about the ennobling virtues of historical curiosity and the impoverishment of the American Jewish imagination.

There were only ever three rules that Pro Musica Hebraica used to govern the selection of Jewish music for the concert stage. First, there would be no obsessive fealty to the Holocaust and the music produced in that dark era of Jewish history. Charles well understood the centrality of lethal anti-Semitism in disrupting the flowering of European Jewish civilization and continuing to endanger Jewish communities around the world. He also loved it when some concert-goer would inquire as to why much of the music sounded sad and minor key. That gave him an opening to quip in response: “Give us a break. We had a rough century.” But he remained adamant that the sacralization of the Holocaust in contemporary Jewish culture was an egregious mistake. The more the seductive idea of “Holocaust music” infiltrated the American Jewish imagination, the more every European Jewish composer came to be reduced to a one-dimensional victim. Jewish musical artists were remembered only for their wartime suffering rather than as complex, flesh-and-blood individuals whose imaginative horizons extended beyond the terrible years of the Holocaust. The cult of victimhood rendered a disservice to art and memory alike.

Second, there would be no Jewish hero worship, no cheap nostalgia for pious ancestors. It was high past time to stop elevating Jewish composers into cartoonish heroes who only braved anti-Semitism and never thought an un-Jewish thought. Not every musical note written by a Jewish hand had to reflect an underlying commitment to religious tradition. Jewish art music represented the beauty and messiness of real lives often lived beyond the strict dictates of the rabbis. For that reason, from the get-go, Charles agreed that there was no question but to include non-Jewish composers who created Jewish musical visions out of traditional Jewish folk and religious sources. There was no racial or genetic test to Jewishness, just as there is none in real life. In the Pro Musica Hebraica version of the Jewish canon, Sergei Prokofiev and Dmitri Shostakovich easily commingled with Salamone Rossi and Mieczysław Weinberg.

Third, any music performed must pass what Charles called the “man in the street” test. That is, it must actually make for enjoyable listening. There would be no historical reenactment for its own sake. There would be no automatic right to performance. It did dead composers no favors to showcase their weaker works merely in the name of some academic standard of completism (no matter how much a scholar might tote a composition’s historical value!). A good Jewish last name could not compensate for an insufferable work of self-indulgent atonality. Nor would Jewish compositions full of saccharine clichés help secure a place for Jewish music in the contemporary classical repertoire. The world did not need any more arrangements of Kol Nidre.

In a way, these stern criteria encouraged concert-goers—Jewish and non-Jewish alike—to listen to the Jewish past without prejudice. It was an invitation to reimagine precisely what took place during the last half-millennium of Jewish cultural life around the world and, equally important, what might be possible going forward. That was also why Charles and Robyn chose “Pro Musica Hebraica,” at the suggestion of Irving Kristol, as the name for the concert series. The Latinate phrase captured something of the classical dignity of Jewish art music. It also served as an invitation to those uber-sophisticated Jewish audiences who did not typically patronize Jewish cultural events to consider their own artistic heritage as the equal of Western civilization.

Each concert’s playbill featured a short note authored by Charles, explaining the program’s theme to the audience. His prose was characteristically taut, sparing in its sentimentality, and focused not on himself but on the music and history at hand. But each note ended with one subtle final gesture, a single line of heartfelt dedication to his late father and uncle. “As always, we dedicate this concert to the memory of Shulim and Simon Krauthammer, devoted Jews whose souls resonated to the magic of this music.” As did the soul of Charles Krauthammer. Yehi zikhro barukh.

Pro Musica Hebraica will continue under Robyn and Daniel Krauthammer with a new season of programming soon to be announced.

Looking for something else to read? We recommend Allan Nadler’s 2016 explanation of how Leonard Cohen helped bring back Old World Ashkenazi cantorial art.

Comments

You must log in to comment Log In

Suggested Reading

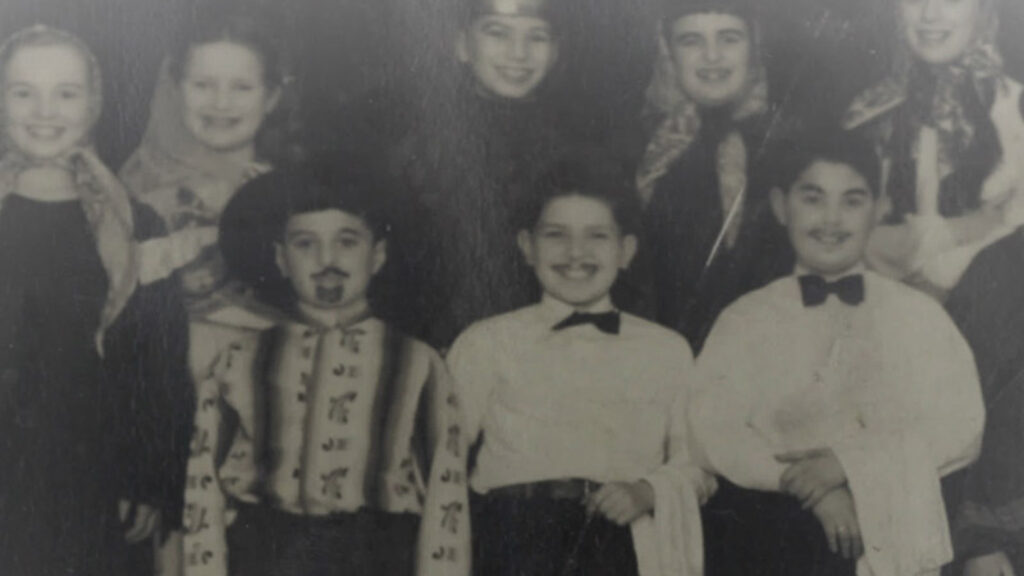

A Tale of Two Cohens: Purim in Montreal

Lyon Cohen wrote and starred in Congregation Shaar HaShomayim's first Purim spiel in 1885--and then led the Montreal Jewish community for half-century. His grandson Leonard didn’t exactly follow his lead, but he does have a big grin in the cast photo of the 1947 Purim Spiel.

Letters, Spring 2021

Of Ballads and Baloney, The Singer or the Song?, The American Question, Against Artichokes, and More

Our Kind of Traitor

More than 40 years after the Yom Kippur War, some of its battles rage on, including the debate over the spy Ashraf Marwan’s true loyalty.

Memory and Desecration in Salonica

Memory and a vandalized memorial in a once-Jewish city on the Aegean Sea.

ajlowy

Fascinating account. One can only imagine how much more of the Krauthammer legacy still remains to be uncovered.